Between landscapes and water lilies, Monet's works from the Marmottan in Paris to the Vittoriano in Rome

Monet. The exhibition, hosted from Oct. 19, 2017 to Feb. 11, 2018 at the Vittoriano Complex in Rome, brings together 60 works by Claude Monet (Paris, 1840 Giverny, 1926), the great father of Impressionism, from the Musée Marmottan Monet in Paris. Works jealously preserved in his Giverny home and donated to the museum by his son Michel in 1966. Lesposition of the works follows a double track: that of chronology and that of stylistic evolution through major themes. The collection includes some great masterpieces such as Portrait of Son Michel as an Infant (1878-1879), Water Lilies (1916-1919), London. Parliament, Reflections on the Thames (1905), Roses (1925-1926).

In the first room, the drawings represent the emergence and awareness of his desire to become an artist. These are caricatures, many of them copied, where well-known figures of the time (1855-1859) are depicted. In the same room we also see some portraits. One is of his son Jean and the other three depict his son Michel as an infant and child. These four works already clearly show how much he was interested in the harmony of colors and how the line was a brushstroke aimed at rendering limpression rather than the faithful and accurate representation of subjects typical of Realism.

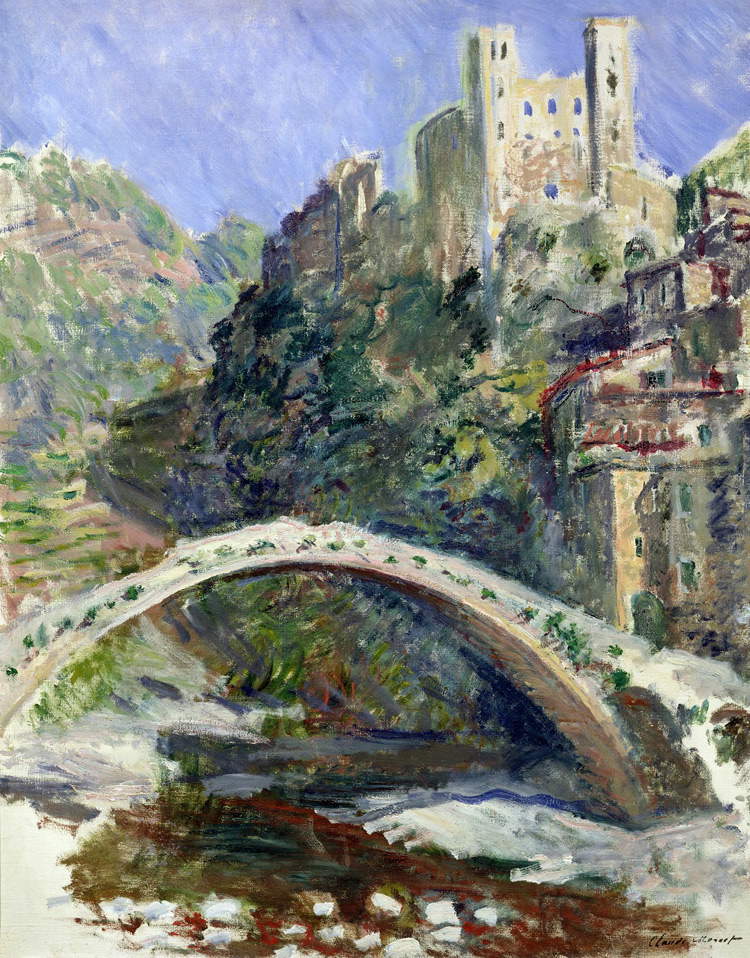

They are followed by the landscapes, at first Nordic, of that dazzling coldness of color din winter, of snow and ice of the places familiar to him around Paris and in Normandy. Then the turning point. In 1883 he made a trip to Liguria, and in 1884 he settled for seventy-nine days in Bordighera. He discovers the light of the south and is enchanted by it. The colors warm and become those of the sun and that warmth that ripens the fruit. The sea is deep blue, the plants exotic and brilliant. In Dolceacqua Castle (1884) another fundamental element of Monet’s painting appears, the bridge, which is not simply a representation of an architectural structure, but an element used to dissect the space of the canvas and recompose it geometrically. A motif that we will find again in his more mature production, the Japanese bridge together with the iron arch of the Avenue of Roses. These views are repeated over and over again: always the same subject and from the same point of view. The hours and thus the colors and shadows change. The color is either denser and almost plastic or it fades and lightens in the more muted hues.

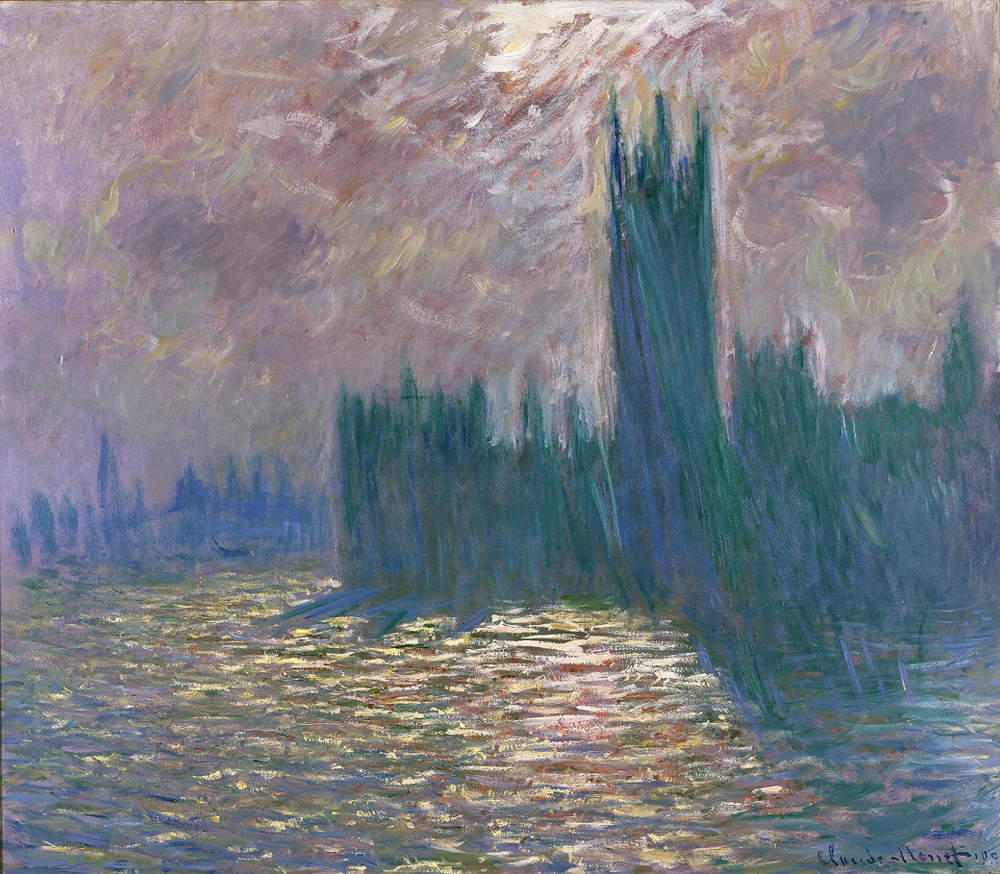

Among the paintings in the exhibition, famous is the one of London’s Parliament reflected in the Thames. Monet did not use black, and the shadow of the great building is tinged with green as the sun peeks through the livid clouds as if after rain and reflects tongues of gold on the river. Venice and London will be the most painted landscapes, achieving great success.

|

| Claude Monet, The Train in the Snow. Locomotive (1875; oil on canvas, 59 x 78 cm; Paris, Musée Marmottan Monet) |

|

| Claude Monet, The Castle of Dolceacqua (1884; oil on canvas, 92 x 73 cm; Paris, Museée Marmottan Monet) |

|

| Claude Monet, London, Parliament. Reflections on the Thames (1905; oil on canvas 81.5 x 92 cm; Paris, Museée Marmottan Monet) |

Monet traveled assiduously with lansia to see and find new subjects, especially after his move to Giverny in 1883. Impossible here, not to quote the words Guy De Maupassant wrote about his friend: Last year, in this country, I often followed Claude Monet in search of impressions. He was not a painter, in truth, but a hunter. He would go, followed by children carrying his canvases, five or six canvases depicting the same motif, at different times of day and with different light effects. He would take them up and put them down again in turn, according to the changes in the sky. And the painter, in front of his subject, would stand waiting for the sun and the shadows, fixing with a few brushstrokes the ray that appeared or the cloud that passed And scornful of the false and the untimely, he would lay them on the canvas with speed I have seen him thus catch a gleam of light on a white rock, and record it with a stream of yellow brushstrokes that, strangely enough, made the sudden and fleeting effect of that rapid and elusive glow. Another time he took in full force a downpour of water that had fallen on the sea and threw it quickly onto the canvas. And it was precisely rain that he had managed to paint, nothing but of the rain that veiled the waves, rocks and sky, barely distinguishable under that downpour.

Hunter of subjects also thanks to a discovery of the time that marks a fundamental moment for painting: the invention of the tube of color that allowed artists to leave the closed studio, stop using pigments and paint en plein air, bringing along the easel to be placed freely.

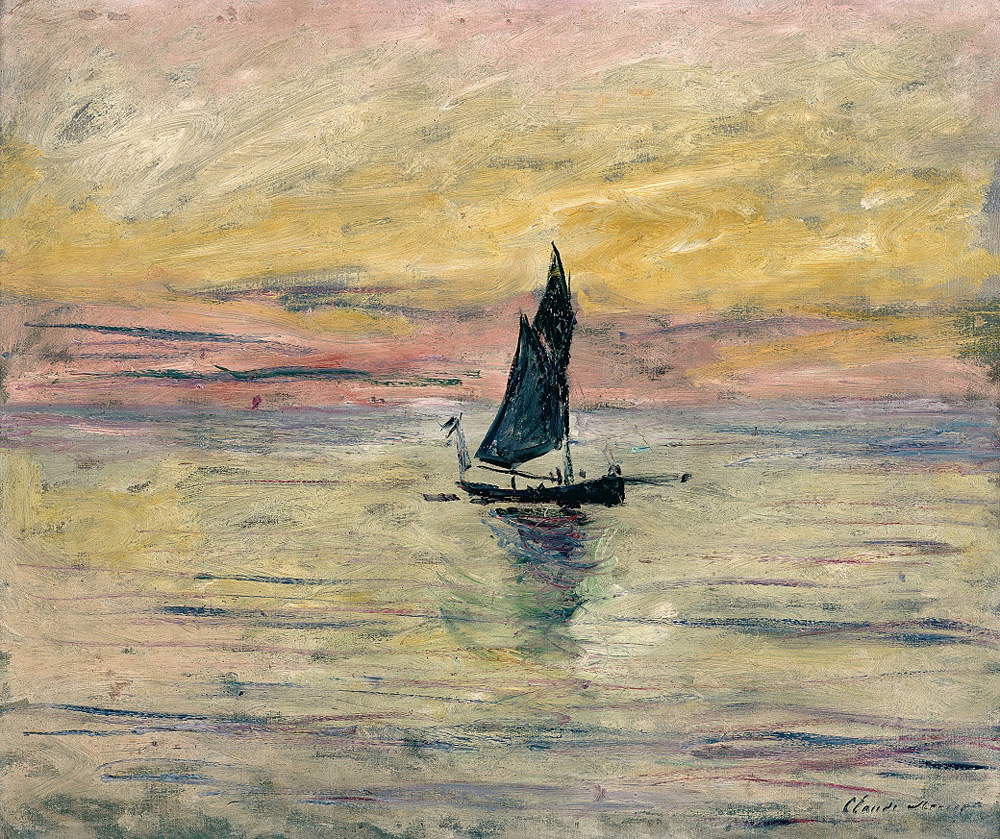

Monet’s subjects are almost always aquatic. Lacqua with its changing glimmer keeps the boats suspended. There will be a moment that Monet enters the secret microcosm of his garden and never comes out again. In 1890 the artist is able to buy the Giverny property and devote himself to the arrangement of the house and garden. Monet builds his personal paradise, as the garden is always identified from the first lines of Genesis and in all periods of art.

|

| Claude Monet, Sailboat. Evening Effect (1885; oil on canvas, 54 x 65 cm; Paris, Musée Marmottan Monet) |

|

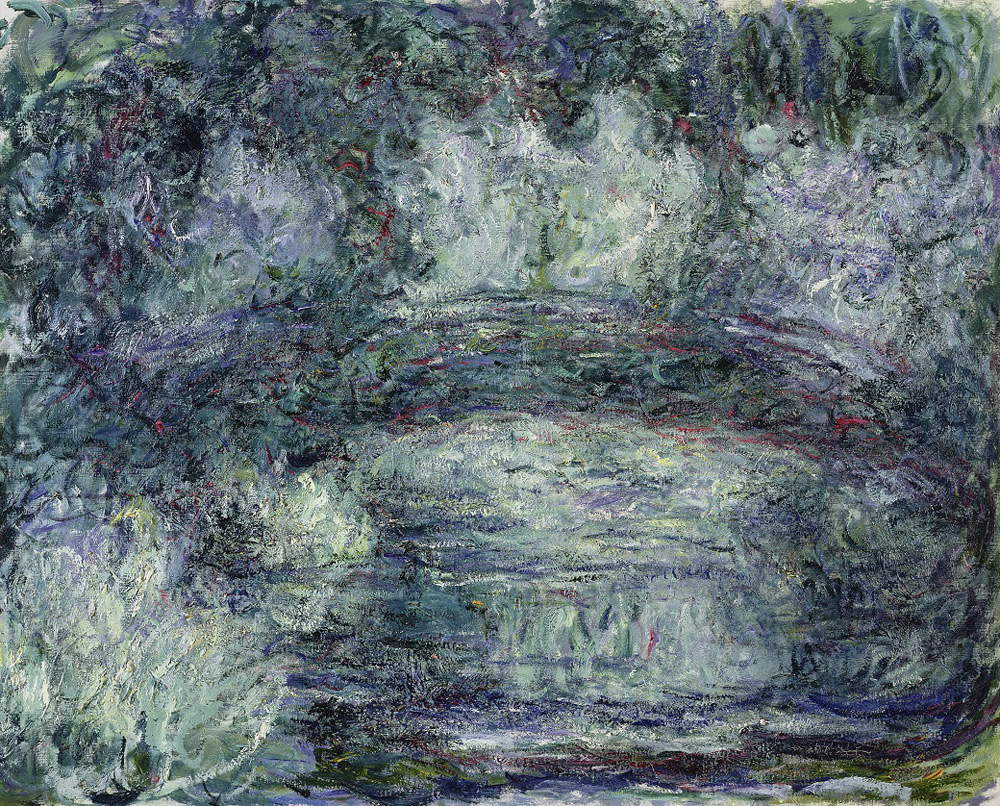

| Claude Monet, The Japanese Bridge (1918-1919; oil on canvas, 74x92 cm; Paris, Musée Marmottan Monet) |

|

| Claude Monet, Weeping Willow (1921-1922; oil on canvas, 116 x 89 cm; Paris, Musée Marmottan Monet) |

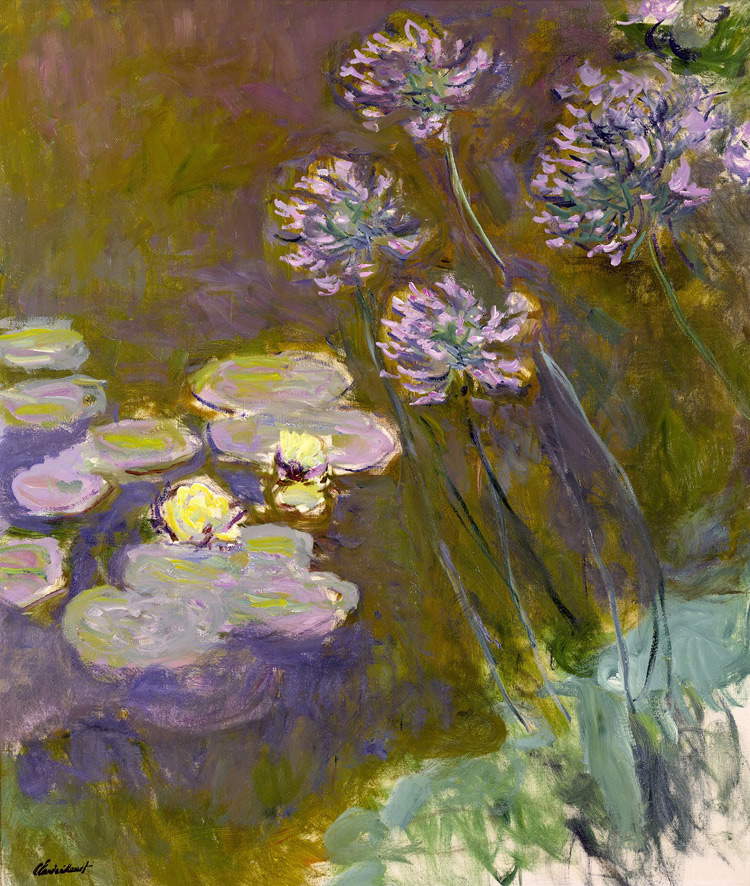

And finally we come to the water lilies. Large, enormous paintings, strange for us accustomed to seeing such formats at that time, devoted exclusively to choral compositions, solemn religious or historical representations. They are large paintings where garden plants stand out, especially his water lilies suspended over the still water of the pool, as if asleep. The changing effects of light on the surface while glimpsing underwater life and the slow movement of the still water.

Writes Monet: It took me a while to understand my water lilies ( ) I had planted them for pure pleasure by growing them without thinking of painting them ( ) And suddenly the magic of my pond revealed itself to me. I picked up the palette. Since then I have hardly ever used any other pattern.

Between 1918 and 1924 Monet tackled his last works divided into three major cycles, the weeping willows, the Japanese bridge and the clos normand, the garden separating his house from the water garden. For Monet it is never interesting to render the details of the subject. He is not interested in distinguishing the different parts of the flower or leaves. We look and recognize what he paints, in animpression. And after the water lilies again water where the soft branches of weeping willows are reflected in it, rendered in different colors and densities.

|

| Claude Monet, Water Lilies and Agapanthus (1914-1917; oil on canvas, 140 x 120 cm; Paris, Musée Marmottan Monet) |

|

| Claude Monet, Water Lilies and Agapanthus, detail |

|

| Claude Monet, Water Lilies (1917-1919; oil on canvas, 100 x 300 cm; Paris, Museée Marmottan Monet) |

|

| Claude Monet, The Roses (1925-1926; oil on canvas, 130 x 200 cm; Paris, Musée Marmottan Monet) |

Finally, the roses in the green-painted iron arches of his garden or the wisteria in bloom. These are large-format paintings, almost retables, where color mixes with form and seems to arise from a mist that cannot be deciphered, but has unseen, never seen, very modern colors. The wisteria as vaporous, spread that looks like a watercolor, the yellows, the acid greens, unseen colors, pure. A purity without blackness. Monet repeats the same subject many times until the forms become indistinct, until the point of no return: that subtle moment when the figurative art becomes abstract. The cleverness of this exhibition’s setting confronts us with an epiphany, a miracle. The figurative art is overcome; we are here, in the present. We perceive the new language, which is ours.

The last work of his life (1925) is dazzling. A blue sky against which roses and leaves are silhouetted. Monet in 1912 suffers from cataracts that substantially alter his visual capacity. His brushstrokes become more and more obvious, textural, and perhaps partly because of this reason he adopts unusually large canvases on which to lay out subjects such as the dilated rose branch against the sky. Apart from painting and gardening, I am a good-for-nothing, said Claude Monet, and we seem to hear again Goethe’s words: The garden is to be understood as a painting. Monet understood it fully.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.