Those who want to see Berthe Morisot’s work from life this fall are forced to split their time between two venues within a couple of hours of each other: GAM in Turin and Palazzo Ducale in Genoa are hosting two exhibitions, both independent, to present to the public the works of the most delicate of the Impressionists, “Aunt Berthe” as she was called at the end of her career, the painter for whom never before innever before in Italy had a dedicated exhibition been organized, contrary to what has always happened in France, where Berthe Morisot, although less well known than a Monet, a Degas or a Renoir, has often been observed under the magnifying glass. Could we have imagined, on this side of the Alps, a single exhibition that would gather everything that could be gathered, capable of holding a stronger position with regard to lenders, that would fully frame Berthe Morisot’s production in its context, and perhaps pull together everything that has been produced on her in recent years? We don’t know, but it certainly would have been better than having two separate and unrelated exhibitions. Of course, it will be said that Berthe Morisot, an artist little known to the Italian public, needed a more popularized occasion to be introduced to our latitudes: in our parts little perhaps interests us in probing the links between Morisot and eighteenth-century art, little interests us in understanding to what extent s’extended on her the suggestions drawn from English painting at a crucial moment in her career (her honeymoon in England after her marriage, in 1874, to Eugène Manet, Édouard’s brother), little do we care about details when there is to be seen an artist whom we know little about. All the more reason, then, to have two exhibitions in two different cities at the same time seems more of a problem than an opportunity: there is no shortage of overlapping, works that would have figured well in one exhibition are absent from the other and vice versa, there are appendices that seem more filler than sinking in dictated by the need to delve deeper, and so on.

Common to both exhibitions is the idea that Berthe Morisot was a central figure in the events of Impressionism, a concept that was well understood by her contemporaries, but which has been lost over the decadesnot so much because of obscurantism about a woman, but, if anything, because of her very personal affair, quite similar, for example, to that of Gustave Caillebotte, another key Impressionist but less well-known to the general public than the various Monet, Degas and Renoir. Admired and reclusive, this was the condition of Morisot and Caillebotte. Both exhibited regularly at the group’s shows (of the eight Impressionist exhibitions organized between 1874 and 1886, Morisot skipped only one), both lived a rather secluded existence despite their strong ties with the other Impressionists, both were well off with their families and thus did not need to paint for a living, which is why the bulk of their works, after their demise, remained at home. It is for this reason that even in France not many of Berthe Morisot’s works are preserved in public museums, at least when compared to the amount of work by her colleagues: this the first brick of a relatively poor critical fortune (of course, not in absolute terms, but always in relation to the other better-known Impressionists). It probably did not help her shy character: “As for her personality, it is well known that she was of the most reserved and reserved; distinct by nature; easily, dangerously taciturn; unaware of imposing an inexplicable distance on anyone who approached her without being one of the great artists of the time.” Thus wrote Paul Valéry, who was a good friend of Berthe Morisot, soon after the painter’s passing.

It is a useful exercise to scroll through his pages and those of Stéphane Mallarmé, another poet, another sincere friend of Berthe Morisot, to grasp all that gentleness, all that delicacy with which the works of a girl, an elegant lady, reserved, who might have seemed distant to those who knew her, but not because she was absent: she was “distant by excessive presence,” wrote Valéry. In the sense that in her eyes the world shone with an abstract, luminous purity, a purity she sought to reproduce with her paintings. With her paintings she sought to express the light and ineffable grace of an afternoon in the garden, of a walk on the beach, of a little girl playing. Capturing this purity, this abstraction, meant being totally present in this abstraction, meant cultivating a delightful, delicate, refined obsession with the occasion, meant consequently appearing distant in people’s eyes. “Every day I pray that the good Lord will make me like a child, and that is to say that he will make me see nature and represent it as a child would, without preconceptions”: so said Camille Corot, who for some time was Berthe Morisot’s master. The lively lightness of her paintings is not a matter of femininity (Berthe Morisot’s femininity is, if anything, to be found in the atmospheres, rather than in the technical elements): even Monet could be just as and sometimes even lighter than Morisot. The lightness is, if anything, a symptom of this total dedication to a reality that is perceived as transient, as well as, as has often been noted, a reflection of his in-depth knowledge of eighteenth-century art: Berthe Morisot’s delicacy is not so far removed from that of a Fragonard. Who was a man.

The stereotype of the bored bourgeois woman who takes up painting as a vexatious feminine pastime is as far removed from Berthe Morisot’s perception of herself. And equally far from reality is the equally stereotyped image of Manet’s model who at some point, for some reason, decides to switch to the other side of the easel. Thus, for no apparent reason. If Berthe Morisot could have, she would have attended art school, which until 1897, however, remained open only to males: alive was the intention to pursue that path, the path of painting, along with her sister Edma, who began studying with her, and then gave up painting altogether after a decade or so, in 1869, when she married (and Berthe would remain reluctant to the idea of marriage for some time having seen what it entailed for her sister). Berthe, on the other hand, since she began taking her first private lessons in 1855 (her and her sister’s first teacher was the sixty-year-old Geoffroy-Alphonse Chocarne: her mother had enrolled them in his school because she wanted them to learn some rudiments to give drawings to her father for his birthday), followed painting until the end of her days. It was her second teacher, Joseph Guichard, who was the first to notice her talent. Berthe Morisot had not yet turned eighteen when she was already skillfully copying the great masters (a copy of her from Veronese’s Calvary , in a private collection, is on display at the Genoa exhibition, a key presence since among the few early works by Berthe Morisot that remain to us: it was she herself who destroyed much of her production in the 1960s, and a small but valuable nucleus can be seen at the Ducal Palace exhibition). Copying the great masters was an activity that Berthe practiced even after 1860, when she moved on to study with Corot, who introduced her to landscape painting (a landscape copied by the master is also on display in Genoa). Usually, Berthe Morisot is painter who is known in medias res, when she is already a formed, solid, mature, independent artist: this is how she is immediately introduced to the public by the Turin exhibition, where the public will find two of the French artist’s masterpieces, Woman with a Fan and Eugène Manet on the Isle of Wight, far apart, in two different rooms, since both exhibitions are built primarily on a thematic basis, a choice that helps to enliven the tour more but at the same time tends to overshadow a little the aspects related to formal research, which perhaps should have been given greater emphasis (more on why later). At those heights, moreover, Berthe Morisot was already selling: she had begun to place her works on the market in 1873, through the gallery of Paul Durand-Ruel. And it was precisely toward the end of that year that she had decided to join the other Impressionists in preparation for the group’s first exhibition, that of 1874, that seminal exhibition whose one hundred and fiftieth anniversary is being celebrated today (in France, to mark the occasion, the Musée d’Orsay has organized one of the most interesting exhibitions in recent years). None of the ten paintings that Berthe Morisot exhibited at the 1874 show are present in the two Italian exhibitions, but one, The Lilacs at Maurecourt, can be seen in Genoa, which is similar in manner and subject matter to the works the artist presented in Nadar’s photographic studio. Berthe Morisot’s main concern in this period is to paint a figure captured in the midst of a moment of everyday life, in an open space, in a natural setting, possibly captured en plein air, according to the teaching of her master Corot: Indeed, art historian Denis Rouart has speculated that it was Berthe Morisot who convinced his friend Édouard Manet to paint outdoors (although Manet would later still have preferred to work in the comfort of his studio, but that is not to say that he did not want to try to open himself up to the new painting that was done outdoors: Le Jardin, Manet’s 1870 work preserved in Vermont, is the first key painting for understanding the artistic relationship between the two, a subject that, however, is only touched upon in the Genoa and Turin exhibitions).

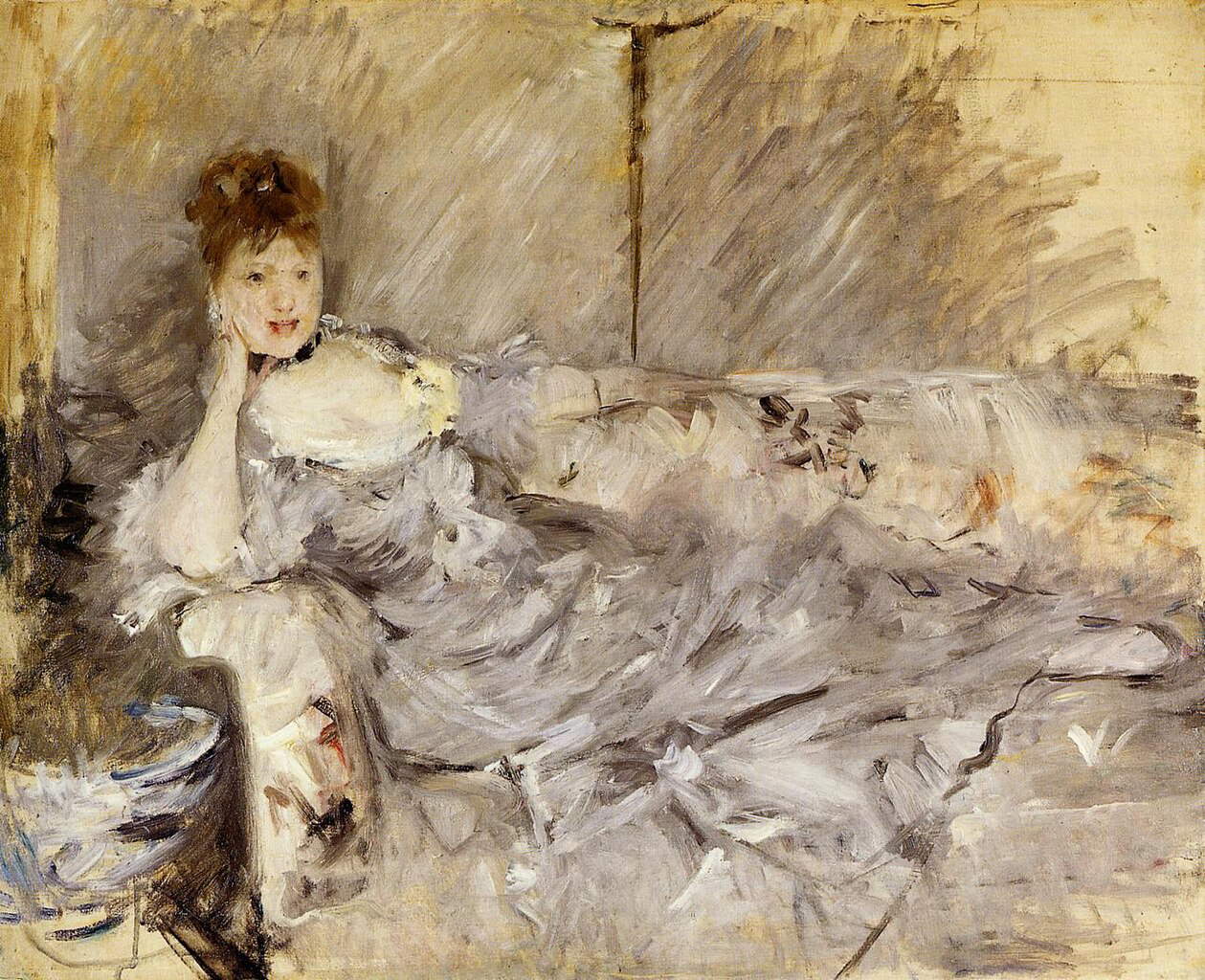

The main shortcoming of the two exhibitions (which, after their respective introductions, proceed rather in parallel: in Genoa a section devoted to Berthe’s daughter Julie, the protagonist of many of her portraits, to which the Family Portraits section of the Turin exhibition responds, and then again in Genoa an evocative chapter on portraiture, given the title L’embodiment of Impressionism, to which corresponds, albeit on a smaller scale, the Women’s Portraits section of the GAM exhibition) consists in the fact that, comparisons with other artists having been reduced to a minimum (in Turin the most interesting, as will be seen, is with a work by Manet, while in Genoa there is a masterpiece by Monet, The Villas at Bordighera, dating from the period of his stay in Liguria), one has some difficulty in grasping the elements in common and, conversely, the divergences from the other Impressionists, beyond the choice of subjects (not that the other Impressionists disdained painting scenes of everyday intimacy, but in Berthe Morisot’s painting they are prevalent), of which both exhibitions offer an adequate sampling. It is true: following Paul Valéry, one can be as he tempted to say "that on the whole her work resembles a female diary, of which color and drawing are the expressive medium .“ The most relevant distinctive element of Berthe Morisot’s art does not lie so much in the femininity of her manners, a femininity that is certainly present, certainly palpable, certainly irrefutable: her distinctive element is perhaps above all that attitude of extreme expressive freedom that leads her to elaborate a painting that is first and foremost atmospheric (the Genoa exhibition makes this aspect more explicit). For that matter, Valéry had also intuited it: ”Canvases made with nothing, a multiplied nothingness of the supreme art of the brushstroke, a nothingness of mists, of shadows of swans, prodigies of the bristle that barely skims the surface. And it is all in this brushing: the time, the place, the season, the knowledge, the immediacy itself, the great gift of reducing to the essential, of lightening the material and thus pushing the impression of the spiritual act to its climax." Berthe Morisot, in other words, is perhaps the most impalpable and ethereal artist of the group, and it is no coincidence that she was the one most closely associated with eighteenth-century painting, the one who had studied it the most and explored it in depth: her method is based on an extremely rapid, fluid brushstroke that barely touches the surface of the canvas, even where the emphasis is on the figure. At GAM this can be seen in Woman with a Fan and, interestingly, it can also be seen in Young Woman among Flowers of 1879, a work by Édouard Manet exhibited alongside Berthe’s paintings to show how the interests of the two were common (in Genoa a similar comparison is with Manet’s Julie with a Watering Can from 1880), while at the Doge’s Palace particularly revealing paintings are The Beach of Nice from 1882, the Young Woman in Stretched Gray from 1879, and all the paintings in the section devoted to Julie.

This attitude matures further in the mid-1980s, when a new problem seems to arise in Morisot’s painting: to understand to what extent a painting can be essential without losing its quality of evoking atmosphere. How immediate a painting can be, how much detail can be spared, in other words how bold one can be. The audience in Genoa take notice of the Maiden with Dog and linger over what appears to be a West Highland Terrier in the little girl’s arms: the little dog’s snout is nothing but a round of quick brushstrokes settled with swiftness and careless precision, the dog’s eye and nose are two spots, the ear looks almost like a brush smear. In Turin this immediacy is most noticeable in the Bambina con bambola on loan from the Musée d’Ixelles, but examples are not few. It is perhaps her experimentalism, rather than the range of her thematic choices, which is indeed rather limited, that makes Berthe Morisot’s painting interesting. From the second half of the 1980s until her death, she will try to accentuate this essentiality by resorting also to the unfinished, as can be seen in some of the paintings in both exhibitions. In Genoa, the painting On the Apple Tree, from 1890, reaches such a degree of abstraction that Berthe Morisot was led to renounce the facial features of both figures (the one below, seen frontally, is particularly interesting: her face is nothing but a neutral oval), or again the Waning Sun on the Lake of the Bois de Boulogne where a few liquid brushstrokes given vertically are enough to suggest the shape of tree trunks, while the imprimitura is left exposed on the lower edge of the 1889 Illuminated Boat , his only nocturne, as the exhibition informs us, featured in the section devoted to his stays in Nice, with interesting set-up reproducing photographs of the port of the Côte d’Azur city as it was at the time. Then there is an unfinished from 1885, in which the painter portrays herself together with her daughter Julie, leaving the lines of the composition visible: Berthe Morisot never stopped experimenting even with drawing, often allowing the composition to be glimpsed even on the painted canvas. Also in Turin, where the subject of Berthe Morisot’s confidence with drawing is more thoroughly explored (in Genoa, on the other hand, there is a focus on etching, another expressive medium to which the painter came in the second part of her career) there are interesting examples of the experimental Morisot of her later years: from the beautiful unfinished of Il flagioletto to the thoughtful fluidity of Il ciliegio (the masterpiece that closes the exhibition), via the swirling green of Ragazza con cane and the total identification of figure and landscape found in La ciotola del latte.

Berthe Morisot is an artist who would perhaps, if presented to the public under the lens of the constant research that animated her intentions, hardly end up boring. And perhaps it would benefit her image more, help to present her better as a true “dissident of the fair sex,” as Mallarmé had called her, but not so much in the sense that the poet intended, namely as a woman who “proposes aesthetics in a way other than with her own person,” but rather in the sense of an artist who was not content to paint what was expected of a woman at the time, but on the contrary stood out as a central figure in the Impressionist movement: her continuous drive to innovate and experiment is comparable perhaps only to that of Monet, her audacity perhaps was unique.

Which of the two exhibitions to visit having the opportunity to choose only one? It basically depends on what one is looking for. The one at the Ducal Palace, curated by Marianne Mathieu, is a reissue of the exhibition Berthe Morisot à Nice. Escales impressionnistes that was held this summer in Nice, totally centered on the artist’s two stays on the French Riviera: in Genoa, the layout of that exhibition was revisited, keeping the nucleus intact but adding a few introductory rooms to introduce the artist to the Genoese public, and a coda on the paintings of Julie Manet, the artist’s daughter, also a painter, moreover the protagonist of an exhibition that the Musée Marmottan Monet dedicated to her between 2021 and 2022. A coda that, however, adds nothing to the discourse on Berthe Morisot artist (indeed: one can even skip it without too many regrets). Just as at the GAM in Turin nothing adds to the comparisons, which seem decidedly forced, with some Piedmontese artists of the 19th century. The exhibition in Turin is organized by theme and curated by Maria Teresa Benedetti and Giulia Perin, who made use of a large number of loans from the Musée Marmottan Monet, integrated, however, in order to offer the public a more complete itinerary, although it lacks some passages (for example, there are no early works). There is, however, a perhaps greater density of important works than in the Palazzo Ducale exhibition, and also to be appreciated in a positive way are the interventions of Stefano Arienti, who designed part of the installations to evoke the atmospheres of Berthe Morisot’s painting, as well as the places she frequented: a presence, that of Arienti, really very interesting, since one perceives with limpid clarity the study, the care, the passion with which Arienti approached Berthe Morisot and with which he tried to return to the public his own loving interpretation. In Genoa, a more linear, and longer exhibition, organized with a rather defined chronological basis on which very vertical insights are grafted (there is, for example, a very amusing focus on her salon-atelier, complete with reconstruction, inspired by the Church of Jesus in Nice and its light, and also displaying the Venus da Boucher that Berthe hung in the center of the room), and which, however, tends to lose strength toward the end. Summing up. Those who want a more traditional layout exhibition and a more comprehensive overview, go to Genoa. Those who already have some background knowledge and want to walk through the atmospheres of Berthe Morisot, go to Turin. Those who feel like it, see them both.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.