Bernini total artist: what the double exhibition at Palazzo Chigi in Ariccia looks like.

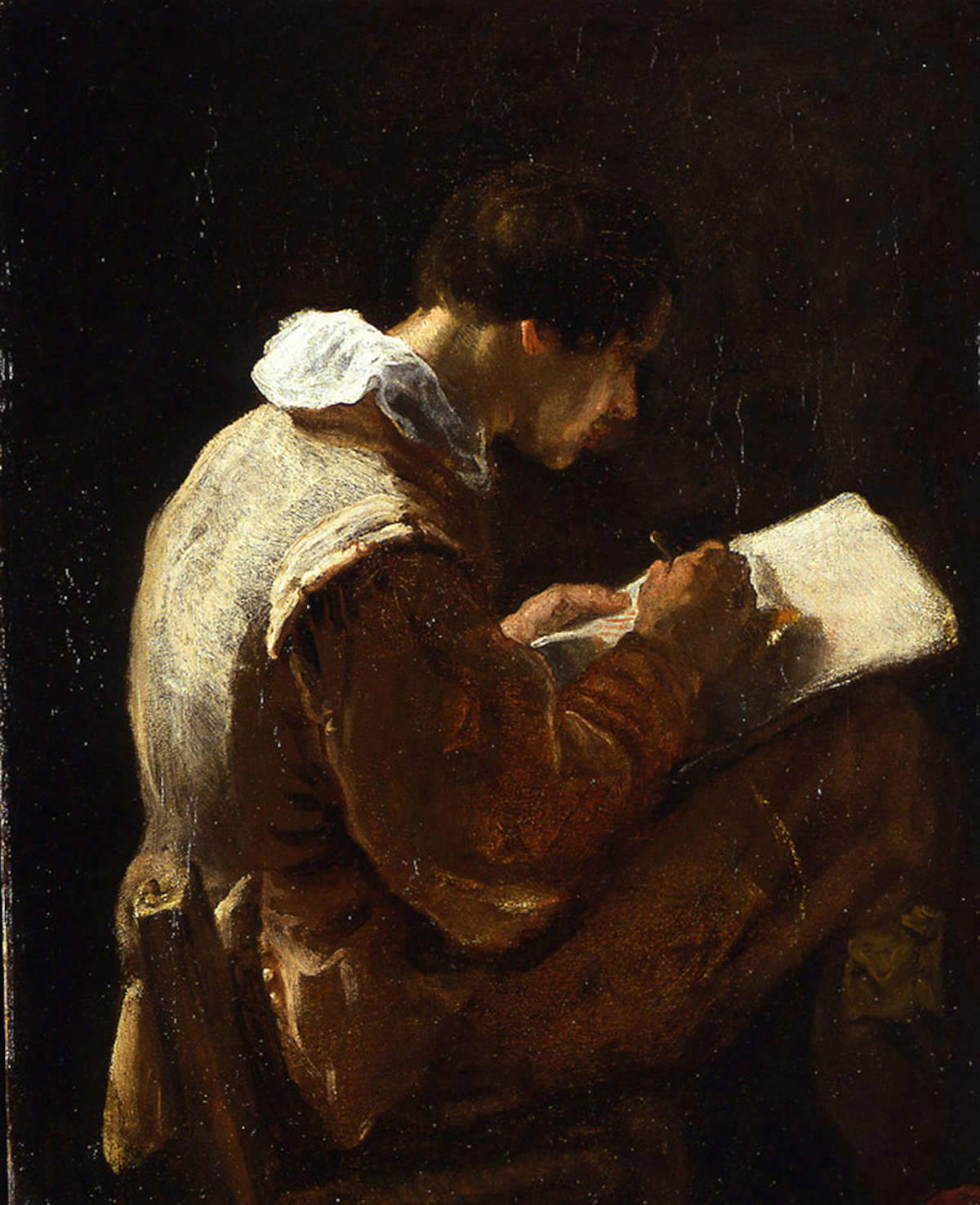

The gilded frames, the mirrors and paintings, the screaming sculpture heads tell of the pomp required by the patrician and the collective effort of the artists to please the gentleman. It is, was, the carriage that, thanks to Giovan Lorenzo Bernini’s 1657 invention, carried and concealed through Rome Flavio Chigi, the cardinal nephew of Alexander VII. This is in the first room on the second floor of the Chigi palace in Ariccia. On the opposite side, in the next room, Bernini himself, but thirty years earlier, depicts himself as, a young painter who arrived as a child in the Urbe that he would help define as the Baroque capital of Catholicism, he is focused on drawing on a sheet of paper illuminated by a light coming from behind him in his darkened room. A light that is all his own, so much so that it is called “Bernina-style,” which will inspire him endless masterpieces.

Two exhibitions in Ariccia, inaugurated Dec. 7, resume until May 18 the discourse on the figure of “Cavalier Bernino” in the center of the Castelli Romani that the artist helped transform with his work on Palazzo Chigi and, on the other side of Piazza della Corte, with the construction of the Church of the Assumption, erected to his design and for the same patrons starting in 1663.

Both exhibitions are curated by Francesco Petrucci, conservator of Palazzo Chigi. And the first one, concentrated entirely in the first room of the floor once reserved for the servants of the princely Chigi mansion now converted into a museum of itself, offers an in-depth look, albeit for a few hints, at the “bel composto,” that is, at that unity of the visual arts (painting, sculpture, decoration, architecture, and so on) put in place by Bernini. The exhibition is entitled The Bernini carriage of Cardinal Chigi. And it takes its cue from the fact that in 2024 the museum in Ariccia came into possession, thanks to a bequest from the Ministry of Culture, of one of the gilded frames that, based on the master’s design, and thanks to the expert hands of Ercole Ferrata, but also of other collaborators, decorated the so-called, lost Chigi “Black Carriage.”

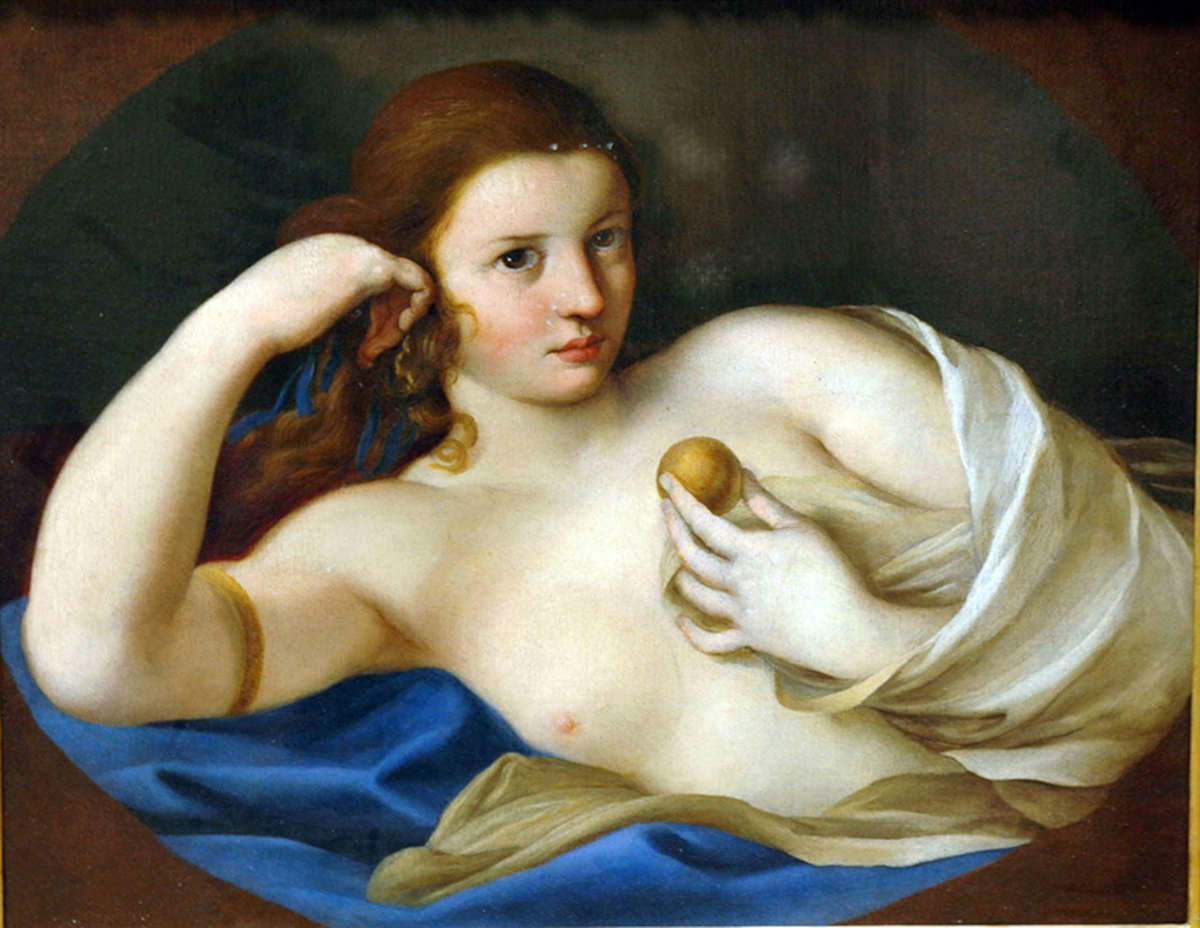

The second, larger exhibition (45 paintings on display) is linked to the first and is entitled Bernini and the Painting of the 1600s. Paintings from the Koelliker Collection. Starting with the acquisitions in the early years of this century, by the wealthy Lombard collector, of some paintings later recorded in Petrucci’s 2006 monograph on Bernini as a painter, the exhibition winds its way through the many rivulets of Baroque painting, by artists of Bernini’s scope but not only, that embellish the collection preserved in the palace on Via Fontana in Milan: mythological themes such as Giacinto Brandi’s The Education of Bacchus, many sacred subjects, primarily a late (1665-69) and moving Pietro da Cortona(Baptism of Christ) made famous in 1962 by Giuliano Briganti, but also profane ones (Andrea Sacchi’s comely Venus with the Golden Apple of 1630). And then biblical stories, such as Samson mauling the lion by Giovanni Lanfranco, coeval with Bernini’s painting of the same subject, but not in the exhibition because it is from a different collection than the Koelliker. But there are also history paintings (the theatrical Alexander the Great kills Cleitus, painted by Mattia Preti in the 1950s) and others with moralistic overtones such as the Portrait of a Penitent Courtesan, by the pseudo Caroselli, which has almost grotesque overtones.

A certainly not exhaustive panorama of Baroque painting in the central decades of the 17th century, that offered by the exhibition. But it is a mirror of the taste of a collector such as Luigi Koelliker, followed in this passion by his son Edoardo, whose paintings (the collection counts about 1,300) is at home in Ariccia since here were hosted in 2005 and 2006 the exhibitions, with works by the Lombard patron, dedicated to Mola and his time and to La ’schola’ di Caravaggio. Also from 2006 is the exhibition in Milan’s Palazzo Reale on the seventeenth-century Lombard painting present in the Koelliker house: a heritage that is not open to the public-not even on Fai days-but which, thanks to the willingness on the part of the collector, has returned to be offered on loan for exhibitions in Italy, after a long period of stop following an absurd bureaucratic mishap.

“To linger in front of a portrait is to meet a person. You look into their eyes and try to understand what is behind them. In portraits it is life pulsing, there is man, there is intelligence of action,” Luigi Koelliker once said. So not still lifes or landscapes, subjects of seventeenth-century genre painting that is absent from the exhibition. But portraits, the soul beyond the face, be it of painters or ladies, prelates or nobles, are undoubtedly the strong and characterizing feature of the exhibition proposal curated by Petrucci, author in the catalog (166 pages, De Luca Editore) of the extensive essay on Bernini’s painting (including some new works not in the exhibition) as well as of all the fact sheets of the works on display.

After the pioneering monographs by Luigi Grassi (1948) and Valentino Martinelli (1950), Giovan Lorenzo Bernini’s apex role in seventeenth-century painting is no longer a novelty, so not only in sculpture, architecture, Baroque festivals and even theater (as his script with I segreti del signor Graziano attests . Comedia ridicolosa republished in 2022 by Succedeoggi libri). And then came, more recently, the Roman exhibitions on Bernini the painter at the Palazzo Barberini in 2007-08 (curated by Tomaso Montanari, who has, however, a narrower view than Petrucci of the pieces attributed to the master in the catalog of his paintings) and of 2017-2018 at the Galleria Borghese.

christ at the column

After all, until a few decades ago few paintings were known from a corpus that the master’s biographer, Filippo Baldinucci, counted in 1682 (two years after the painter’s death) at as many as 150 paintings, including those left in the homes of his sons, the many in the princely residences of the Barberini and Chigi families, but also the others scattered in the palaces of other Roman families. Of the young man who in 1624, at the age of 26, was called upon as a “painter” and with other of his colleagues - Roncalli, Cesari or Lanfranco - to certify that the “miraculous” blood stains on a precious relic preserved at the Chiesa Nuova “are not done in gouache ... nor could they have been done in oil” (as revealed by Sofia Barchiesi in Giardino di conversazioni, writings in honor of Augusto Gentili published in 2023), in Ariccia we have the coeval Autoritratto mentre disegnegna (Self-portrait while drawing ) which, whether done in the mirror or not, offers a true beacon on the great artist’s private life. Bernini depicted himself (or they did) in humble but decorous work clothes as he awaits the drawing that, developed in every form and technique of art, later made him famous. Of a different fashion, and a direct look into the eyes of the viewer, is made instead the dress of the man whom Petrucci believes he identifies as the poet Virginio Orsini, who died in 1624 at only 29 years of age. And also attributed to Bernini is the beautiful portrait (perhaps it was Luigi, the artist’s brother and trusted collaborator, who posed) purchased by Koelliker in 2005 from a Swiss collector: the man’s face comes into the foreground light emerging from the darkness of the background; and typical of Bernini, Petrucci argues, are “the inquiring expressive vividness and above all the ability to create a relationship of empathy with the sitter.” On display in the same room are Christ at the Column, between Titian and Rubens, from 1625-30, and The Reclining Levantine (1648-50), the other two paintings attributed to the hand of the Baroque genius who also transposed the plasticism of sculpture into painting: one has to keep in mind the eyes of Luigi Bernini to find a similar frown in some of the portraits in the other rooms but by other authors. Like the somewhat bully-like self-portrait by Jan Miel (circa 1650), or the one, same mustache and goatee, by Jan Van den Hoecke (circa 1640). All the way to the Venetian “Nicolò Sagredo” with a swaggering gaze in the portrait executed by Borgognone (born Guillame Courtois) or that of a prelate with long, caned hair, traced to the hand of Baciccio (Giovan Battista Gaulli).

Not part of the exhibition itinerary, but not to be missed, is the extraordinary clypeus with St. Joseph and Child signed and dated (1663) by Giovan Lorenzo Bernini. The work is located on the wall of the chapel on the main floor of the Chigi Palace. It is therefore sufficient to descend the grand staircase to admire the beauty of a Bernini sanguine that stands comparison with the art of Bernini painter. And to contemplate the figure of the saint/ carpenter who-with an almost maternal tenderness, in the wake of Guido Reni’s identical subject, but also of the classical sculpture of “Silenus with infant Dionysus”-cares for his Son. And Petrucci rightly points out the non-coincidental coincidence of the arrival in 1662, after two girls, of a son for Agostino Chigi, protector of the artist. But also the words, highlighted by Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco, found in the great master’s will: the “Cavalier Bernino recommended his soul [...] to all the saints [...]: Saint Joseph particularly, patron of artisans, who assisted him in his difficult work as a father.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.