by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 14/01/2018

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'Bernini' in Rome, Galleria Borghese, November 1, 2017 to February 20, 2018.

Exactly four hundred years have passed since a barely nineteen-year-old Gian Lorenzo Bernini (Naples, 1598 - Rome, 1680) delivered, to Cardinal Maffeo Barberini, the future Pope Urban VIII, the Saint Sebastian now in the Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid: so young was the artist that it was his father who had to collect the payment. “A dì 29 dicembre scudi cinquanta moneta buoni al sudetto [Pietro Bernini] pagati per prezzo di una statua di marmo bianco di un san Bastiano”: so reads, unequivocally, the document found in 1998 that made it possible to date the work later finished in Spain, as well as to confirm without any doubt its Barberinian commission. Instead, a twenty-year period has passed since the early summer day when the place that houses the world’s highest and densest concentration of Bernini works, namely the Galleria Borghese in Rome, reopened its doors after a long restoration that had kept it closed for sixteen years. Natural, then, to expect this double anniversary to be celebrated in the most fitting manner: a major exhibition on Bernini, coming to the halls of the Borghese Gallery twenty years after the exhibition on Bernini’s youth then organized in order to celebrate the reopening of what was once the residence of Cardinal Scipione Borghese.

An exhibition on Bernini is probably the only one that makes sense to set up in the almost intact premises of the Borghese, which in recent years, moreover, has accustomed us to rather risky actions, including sumptuous displays of clothes by à la page fashion designers, improbable comparisons between ancient and modern artists, and exhibitions of individual masterpieces, extraordinary but far removed in historical and cultural environment from the context of the historic Roman residence. Of course: the problem of any exhibition set up in the Gallery (a problem from which even the most necessary and scientifically grounded exhibitions are not exempt) is represented by the difficulty of making the practical and logistical reasons for an exhibition coexist with the historical environments of the Gallery since, on the one hand, any temporary operation would end up altering the delicate historical-artistic balance of the Borghese, and on the other hand the exhibition, in order to be as unobtrusive as possible towards the Gallery itself, could be forced to give up the coherence of its own path. Different, at least in some respects, is the discourse for an exhibition dedicated to Bernini: much of the material on which to set the discourse is already present in the Gallery, so much so that the most spectacular images disseminated to present the event to the public are none other than the images of the most significant masterpieces of the permanent collection. And we would indeed have been surprised otherwise.

Yet, even the Bernini exhibition (this is the laconic title, perhaps justified by the fact that, in front of such a name, there is no need to add anything else) presents those limitations with which every exhibition set up at the Borghese Gallery must necessarily measure itself. Add to this the perplexity aroused by some passages, which will be discussed in more detail later in this contribution, and one will come to the conclusion that, perhaps, presenting the public with an extraordinary and exceptional parade of masterpieces such as the one skillfully and intelligently collected thanks to the work of curators Andrea Bacchi and Anna Coliva, is not a sufficient condition to let the visitor leave without a few too many doubts about the effectiveness and coherence of the exhibition. If we wanted to use a superlative that is as elementary as it is effective, we could call the exhibition “beautiful”: there are almost all the removable masterpieces of the great artist who inaugurated the Baroque season, and further merit of the curators was to extend the exhibition’s topics to include insights into Gian Lorenzo’s father, Pietro Bernini (Sesto Fiorentino, 1562 - Rome, 1629), whose critical fortunes seem to be steadily rising. However, as much as the sheer volume of capidopera has moved us all to expressions of joyful amazement, it is necessary to ask whether the emotions one undoubtedly feels in front of such works are able to amend the tortuousness of a sometimes unsatisfactory itinerary.

|

| Borghese Gallery, entrance set up for Bernini exhibition |

|

| First room of the Bernini exhibition at the Borghese Gallery. |

|

| The room with the sketches of the Fountain of Rivers: evident the jarring of the arrangements with the context |

The exhibition kicks off from the hall with Mariano Rossi’s frescoes, inside which is a large section on Gian Lorenzo’s earliest activity: in this case, this part of the exhibition aims to illustrate his apprenticeship with his father Pietro, displaying several of the sculptures that father and son made together, although there is no shortage of work done by Pietro alone. We begin with the Satyr astride a panther, a marble garden sculpture that was commissioned from the artist by the Corsi family of Florence, and which later ended up on the antiques market (today it is preserved in Berlin): the spiral movement of this group, which was intended to adorn a fountain, is still tied to Mannerist patterns that even the young Gian Lorenzo, in the undertakings he made together with his father, could in no way escape. A clear example is a sarcastic and amusing work such as the Faun harassed by putti (not to be missed is the detail of the putto annoying the satyr by sticking his tongue out at him), whose attribution to the hand of Pietro and Gian Lorenzo Bernini was the merit of Federico Zeri, after it had first passed at auction as an anonymous sculpture from the second half of the 16th century, then as a 19th-century work. Complicated work that exudes virtuosity from every single piece of it (amazing the alternation of full and empty spaces that almost disorients the observer) and also, like the Satyr astride a panther, designed to be seen from every possible angle, it presents not a few difficulties in identifying the hands of the two artists, a subject on which there has long been debate without, however, reaching definitive conclusions: the sculpture, indebted as much to the ancient tradition as to Carracci’s classicism, demonstrates an invention still linked to late 16th-century stylistic features, but at the same time manifests an extraordinary vitality that will be characteristic of Gian Lorenzo’s sculptures and that, together with other details (the panels in the room invite us to observe the rendering of the trunk and epidermis, for example, but we could also add the movement of the limbs and the diagonals on which the composition is set), betrays the presence of the sculptor, who was around seventeen years old at the time.

Similarly the result of the collaboration between Bernini senior and Bernini iunior is the cycle of the Aldobrandini seasons, made around 1620, at least according to the not very recent hypothesis of Andrea Bacchi, who, although without the unanimous approval of critics because of the too vague references in the document, wanted to link the works to a payment made in 1622 by Leone Strozzi, a member of the well-known Florentine family, who would thus turn out to be the commissioner. A matter of a few years, however, since, before the note was found, critics used to date the Aldobrandini Seasons, also surprising for the liveliness and originality of some of the inventions, to around 1615: the visitor will not be able to erase the memory ofWinter, wrapped in a heavy sheepskin cloak and with his head covered by a wide headdress, to the point that we can only make out the figure’s eyes. A “shepherd of the Roman countryside,” as Federico Zeri had dubbed him, “halfway between the burino and the Phrygian caped prisoners of the Arch of Septimius Severus”: it is a work to be ascribed to Pietro Bernini. IfSummer, clumsy and heavy, is the least successful of the four sculptures that make up the series, the same cannot be said of Spring andAutumn, both works that scholars have believed to have been executed by four hands (and it was Zeri again who first launched this proposal): extraordinary is the bouquet that Spring holds in her hand and whose flowers descend to adorn the bull at her feet; daring is the pose ofAutumn, with her arm supporting an unlikely festoon that becomes a sort of arbor that almost makes the figure look like some sort of extravagant architecture and leads us to attempt comparisons with the Faun in the Metropolitan. This first confrontation between Peter and Gian Lorenzo is one of the exhibition’s main points of interest: the public has the opportunity to follow the young Gian Lorenzo in his early works together with his father, is able to identify with some ease the motifs that identify their respective personalities, and as the tour continues, has a way to see, with works arranged within a good and gradual progression, the way in which the son will succeed in surpassing his father. And for scholars, the possibility of making direct comparisons between works otherwise kept in museums far apart.

Instead, the presence, in this first section, of the Truth Unveiled, a work of Gian Lorenzo’s maturity for the occasion moved a few rooms, and especially of the Saint Bibiana, which besides being out of the chronological boundaries of the section (it is in fact a work of the mid-1920s, and is perhaps located in the first hall, along with the Truth, because the Borghese’s premises would not have allowed for different solutions) is also out of context, since the sculpture is kept in the church of Santa Bibiana in Rome, which is three kilometers from the Borghese Gallery and represents the place for which the work was conceived: it will then be possible to justify its presence in the exhibition because of the recent restoration to which the work has undergone (given the now established custom of launching major restoration campaigns in proximity to exhibitions), and certainly the importance of the event is enhanced by the possibility of hosting the first public work executed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, with which there is a notable change in stylistic register, marked by the rendering of sentiments and those wavy, almost vibrant draperies that will become a constant in Bernini’s art, but perhaps the exhibition would not have been affected by a presence of Saint Bibiana inside her church. It is always a matter of subtle balances.

|

| Pietro Bernini, Satyr Riding a Panther (1595-1598; marble, 138 x 80 x 85 cm; Berlin, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Skulpturensammlung und Museum für Byzantinische Kunst) |

|

| Pietro and Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Faun Harassed by Putti (c. 1615; marble, 132.4 x 73.7 x 47.9 cm; New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art) |

|

| Pietro and Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Primavera (c. 1620; marble, 125 x 34 x 39.5 cm; Private Collection) |

|

| Pietro Bernini, Summer (c. 1620; marble, 126 x 38 x 35 cm; Private Collection) |

|

| Pietro and Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Autumn (c. 1620; marble, 127 x 47 x 50 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Pietro Bernini, Winter (c. 1620; marble, 127 x 50 x 37 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Santa Bibiana (1624-1626; marble, 185 x 86 x 55 cm Rome, Santa Bibiana) |

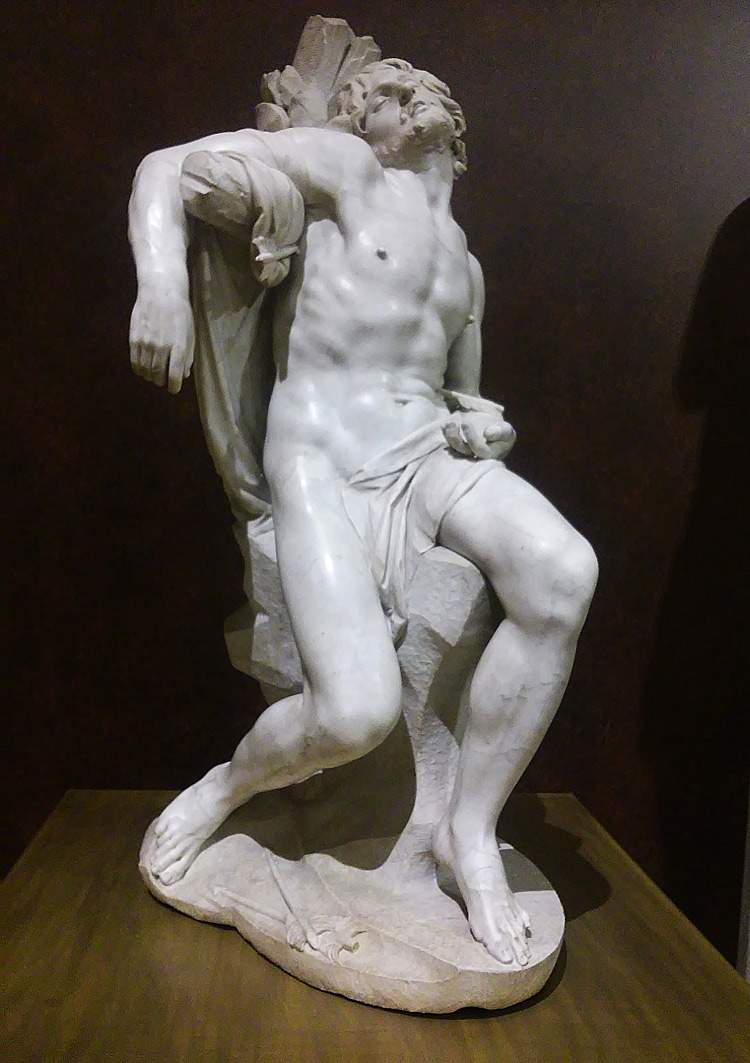

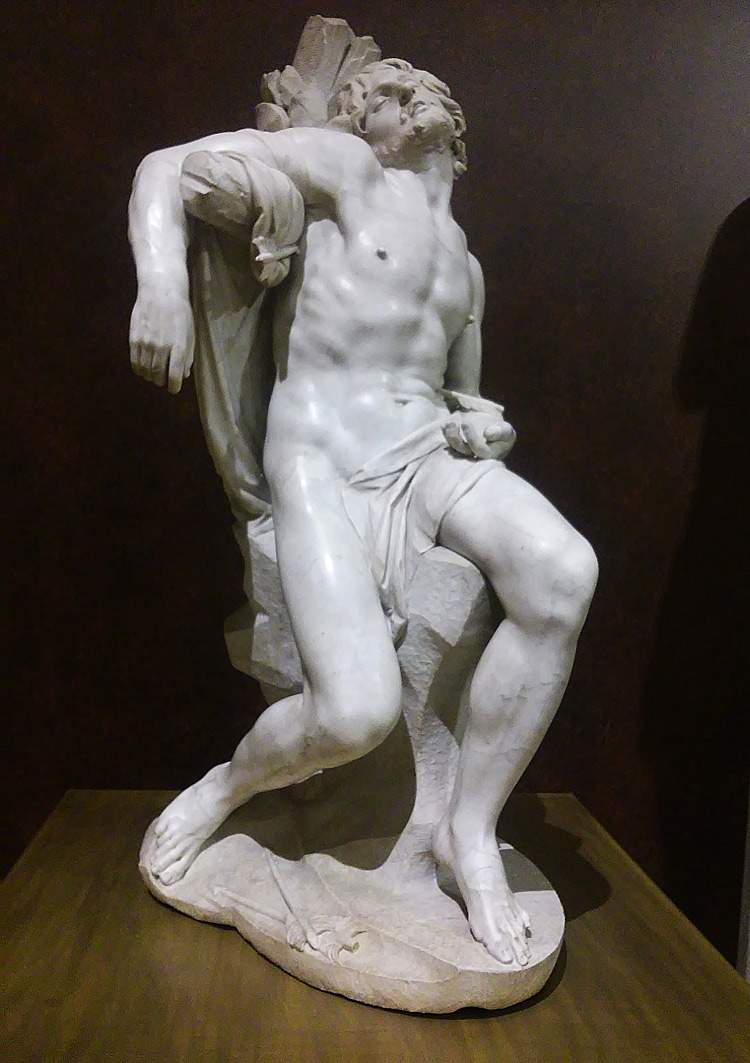

In the Sala del Sileno, the one that usually houses Caravaggio’s works, the public will encounter other notable and fundamental early works by Bernini: one of these is precisely that Saint Sebastian mentioned in the opening, caught in the act of abandoning himself, with his body so finely modeled, to the delirium caused by the arrows that, according to the hagiographies, did not kill him, but merely wounded him. In the exhibition, the work is presented as the “first fully Baroque statue in the history of art,” a statement that is certainly not incontrovertible, since other scholars have often shown different sentiments (for example, a few years ago Francesco Petrucci, one of the authors of the essays in the catalog, attributed primacy to the St. Longinus of St. Peter’s Basilica): in any case, the St. Sebastian is a work in which one appreciates the already found autonomy from his father’s models, with the intensity of that soft abandon and with the delicacy of the modeling (almost Correggioesque or Baroque, as several scholars have pointed out) that succeed in definitively overcoming Peter’s lesson. The use of a sculpture characterized by that strong emotional impact that will be typical of the Baroque is now full in theAnima beata and especially in theAnima dannata, with the face of the latter shocked by a scream that is more belligerent than human: a work that goes beyond the mere involvement of the sense of sight (one almost seems to hear it, that heart-rending cry), which Bernini probably modeled by placing himself in front of a mirror to mimic the expression of his terrible character, and which Cesare Brandi suggested should be juxtaposed with Caravaggio’s naturalistic experiments (such as the Medusa now in the Uffizi, which might have set a precedent for theDamned Soul).

With the Egyptian Room, we return to investigate the relationship between Pietro and Gian Lorenzo with the Putto sopra a drago, which arrives from the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, and especially with the celebrated Capra Amaltea, the sculpture depicting the mythological animal that suckled Zeus on Mount Ida: in the exhibition itinerary it is assigned to a very young Gian Lorenzo, with a date before 1615, but the visitor is nevertheless informed of the doubts about the sculpture’s attribution because of the difficulty of reconciling it with the artist’s other early works. The catalog entry compiled by Stefano Pierguidi illustrates more thoroughly how "the almost ungrammatical character of certain passages in the Capra, particularly the hair of the two putti, could be explained by the inexperience of the very young Gian Lorenzo, perhaps really left completely alone by his father Pietro to handle the piece that was supposed to show Scipione [Borghese] his precocious genius." Therefore, if many have accepted the hypothesis of a work referable to the hand of a child Gian Lorenzo and datable to about 1609, Andrea Bacchi has even gone so far as to raise doubts about the autography of the group, all the more so since in ancient times the Goat was listed as an anonymous sculpture: this uncertainty was not, however, sufficient to prevent the Goat from appearing, in the exhibition, with the now customary attribution to Gian Lorenzo.

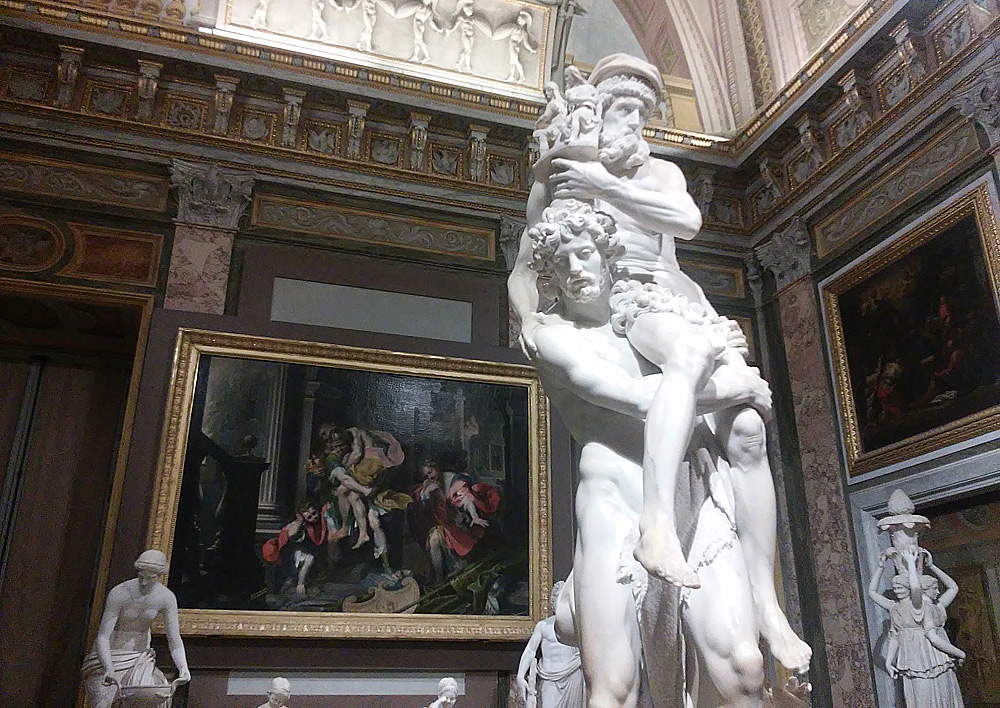

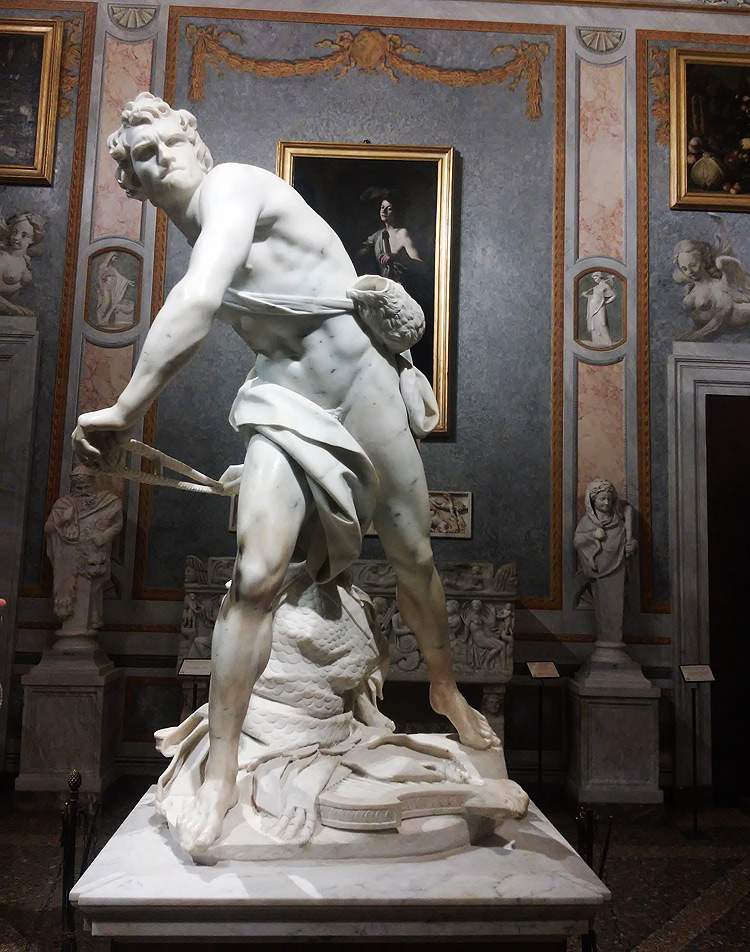

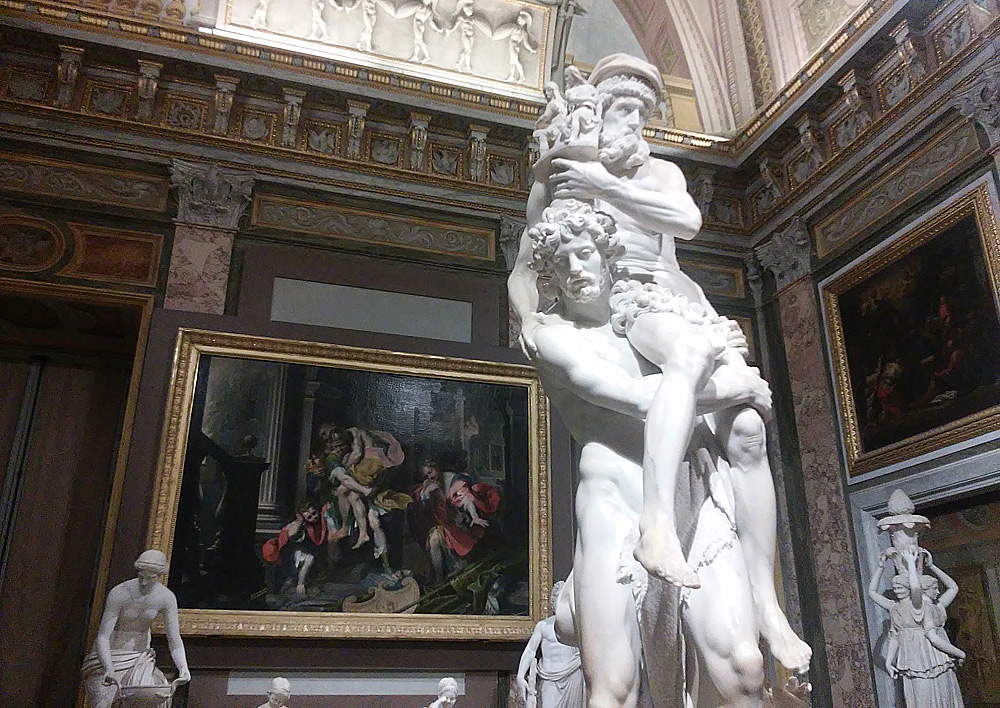

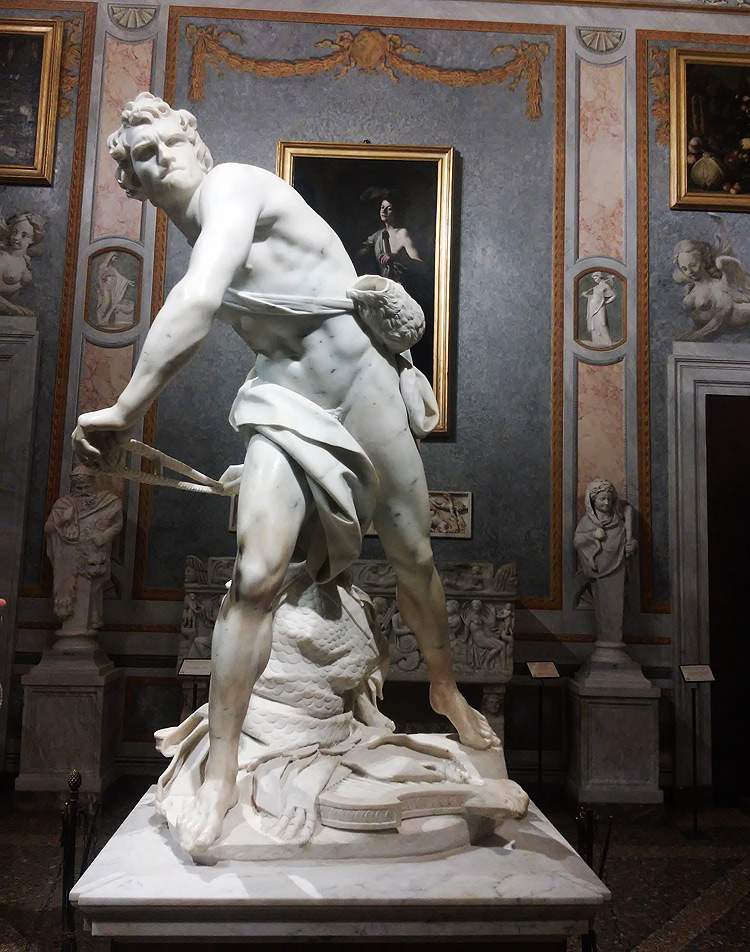

As for the section on restorations, it is worth mentioning the presence of theHermaphrodite, which returns to Rome in the very room where it was located before being sold to the French occupiers who then took it to Paris (it is now kept in the Louvre): the soft white Carrara marble mattress, donated to the ancient sculpture dating back to the second century AD, is the work of the young Bernini (it dates back to 1620), who certainly performed a daring operation with such an insert, but was able to increase the great sensuality that characterizes the sculpture. Having passed the Hall of the Hermaphrodite, one can throw oneself into the Berninian jubilation that are the rooms in which the Borghese groups are preserved, iconic icons of Bernini’s unquestionable genius: in rapid succession, the Aeneasand Anchises, the Rape of Proserpine,Apollo and Daphne, and the David. The Aeneasand Anchises (1618-1619) is a work that reveals Raphaelesque suggestions (the reference is to the Stanza dell’Incendio di Borgo, but a certain link with his father’s manner also returns in the spiral movement of the protagonists) and is placed in an evocative dialogue with Federico Barocci’s Escape of Aeneas from Troy, usually exhibited in the picture gallery: the first of the sculptural groups commissioned from a Bernini then in his early twenties by Cardinal Scipione Borghese, it will be closely followed by the Rape of Proserpine (1621-1622), still mindful of Mannerist virtuosity, a work before which one loses track of time, and a sculpture that always leaves one stunned, every time one admires it, by the softness of the marble that becomes living, pulsating flesh. We then come to the room where we findApollo and Daphne (1622-1625), a work in which Baroque theatricality reaches its highest forms and where the drama, like the Rape of Proserpine, touches its most exciting climax, and we finally arrive at David (1623-1624), very different from all those that had preceded it in that it is captured in an instant, in a fraction of a second, in the tension of a precise moment. And at the end of the itinerary, the two works by Peter that we encounter in the Pauline Hall,Andromeda and Virtue Subduing Vice, totally out of place unless one wants to take a forced path between the rooms, struggle not a little to keep up.

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Saint Sebastian (1615; marble, 98 x 42 x 49 cm; Madrid, Private collection on deposit at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum) |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Anima Beata (1619; marble, 38 cm without base, antique yellow base 19 cm; Rome, Spanish Embassy to the Holy See, Spanish Palace) |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Anima Dannata (1619; marble, 38 cm without base, base of antique yellow 19 cm; Rome, Spanish Embassy to the Holy See, Spanish Palace) |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, The Goat Amaltea (before 1615; marble, 45 x 60 cm; Rome, Galleria Borghese) |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Materasso dell’Ermafrodito (1620; Carrara marble, 16 x 169 x 89 cm; Paris, Musée du Louvre) |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Aeneas, Anchises and Ascanius Flee from Troy (1618-1619; marble, 220 x 113 cm, base size 99 x 79 cm; Rome, Galleria Borghese) |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Rape of Proserpine (1621-1622; marble, 255 x 109 cm; Rome, Galleria Borghese) |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Apollo and Daphne (1622-1625; marble, 243 cm excluding base 115 cm, base 130 x 88 cm; Rome, Galleria Borghese) |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, David (1623-1624; marble, 170 x 103 cm; Rome, Galleria Borghese) |

|

| Pietro Bernini, Andromeda (c. 1610-1615; marble, 105 x 45 x 38 cm; Bergamo, Accademia Carrara) |

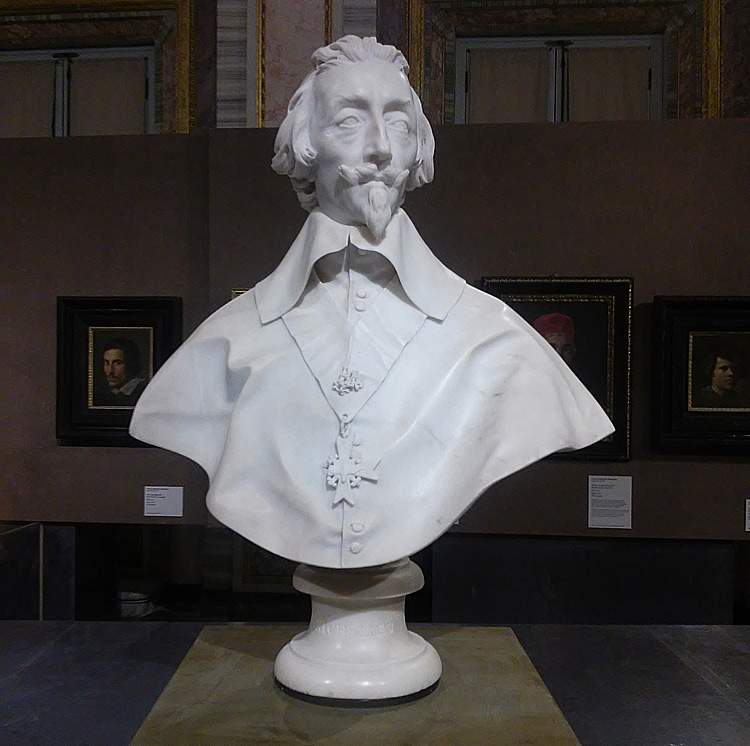

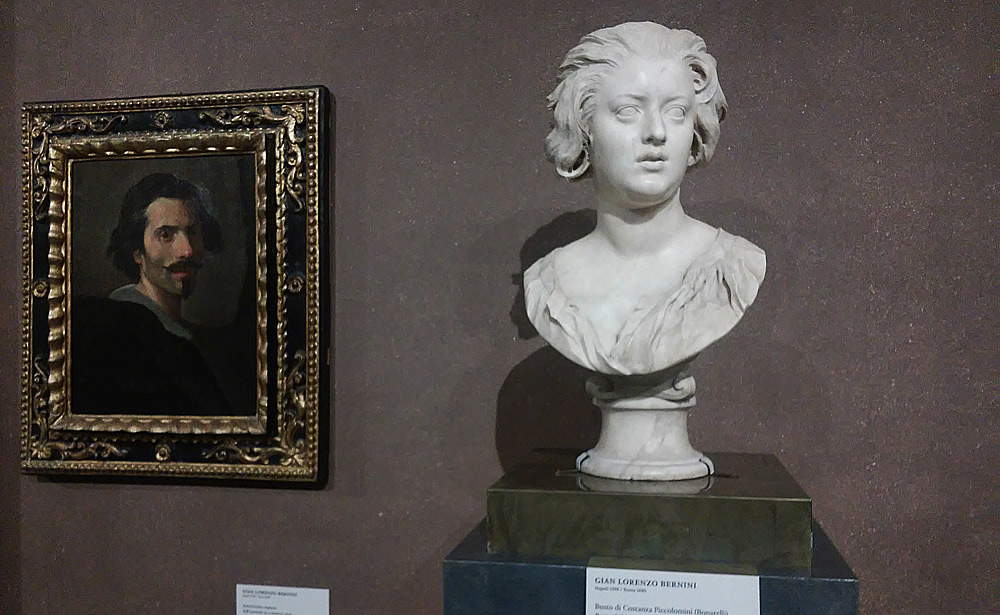

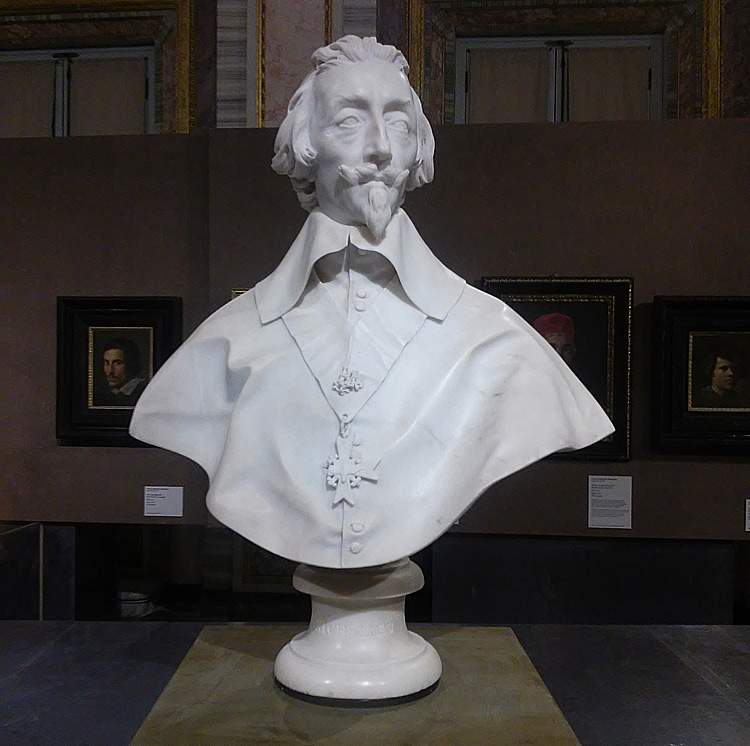

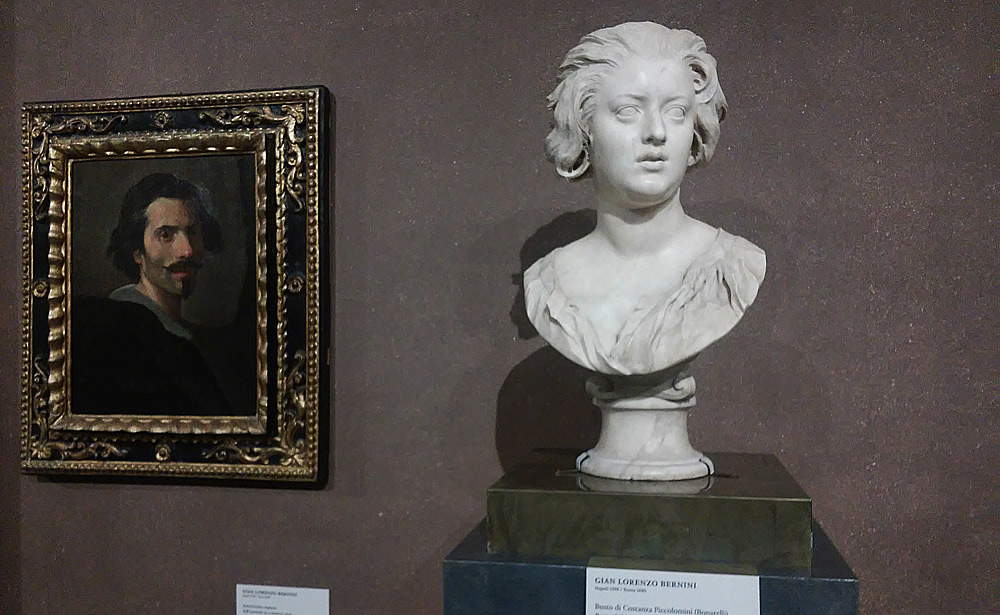

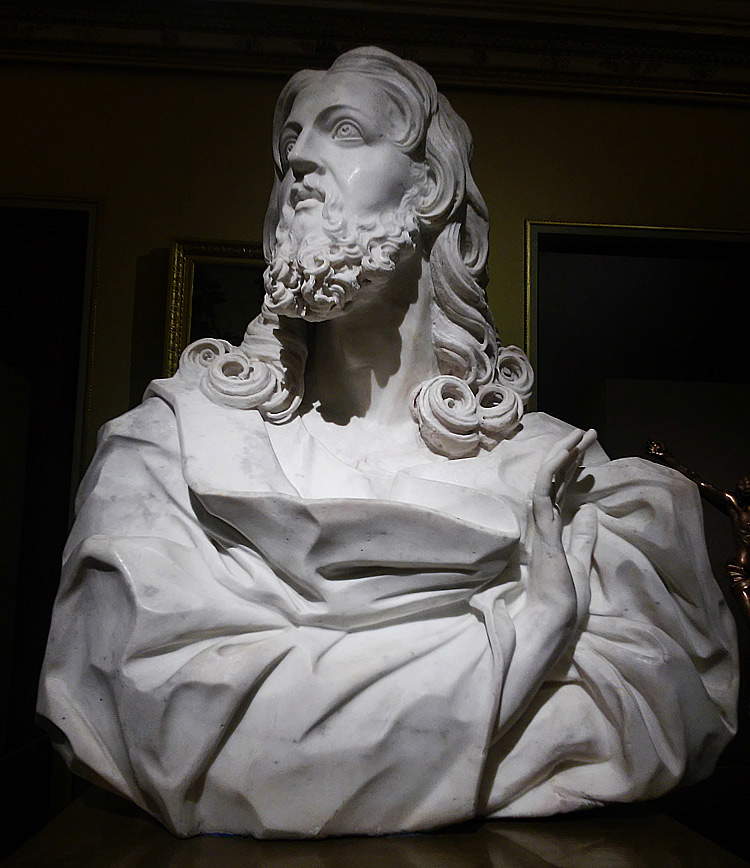

The stairs leading to the upper floor, that of the picture gallery, allow us to reorganize our ideas and prepare ourselves for the parade of busts and paintings we find in Lanfranco’s Loggia. It is difficult to account for the entire mighty series of portraits that the curators have, with great merit, brought to the Borghese Gallery, but it is possible to start with an interesting observation by Francesco Petrucci in his catalog essay. The scholar, in particular, suggests subdividing Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s portraits into three major groups: “a first type corresponds to the youthful busts, where a concern for verisimilitude and conformity to nature prevails; a second focuses on the search for instantaneity and emotional disturbance; a third pursues an extratemporal dimension of superior dignity of the subject, landing in the so-called ’great manner.’” To the first case can belong the Bust of Antonio Cepparelli (1622-1623), in which a 24-year-old Bernini is concerned with rendering his subject as closely as possible to reality. To the second, however, we ascribe one of the most exciting works in the exhibition, the Portrait of Costanza Bonarelli (ca. 1635): the young woman, born Piccolomini, had married the Lucchese sculptor Matteo Bonarelli, but had become the mistress of Gian Lorenzo and at the same time of his brother Luigi, a situation that led to a heated quarrel between the two and ended up escalating violently (Bernini ordered one of his servants to scar poor Costanza). However, when things were still going well between the two lovers, Gian Lorenzo depicted Costanza in one of the most sensual portraits in all of art history: the girl is visibly excited, her hair disheveled, her shirt generously open, as if the young woman is just getting dressed after a love encounter. It is a vivid portrait, filled with sincere and direct passion, representing one of the high points of Bernini’s entire production. Finally, in the third group we can include the bust of Cardinal Richelieu (1640-1641), which, executed from a painting, shows that solemn character typical of Bernini’s later portraiture. Next to the busts is a series of paintings by Bernini, on some of which, however, critics disagree as to their authorship by the great artist.

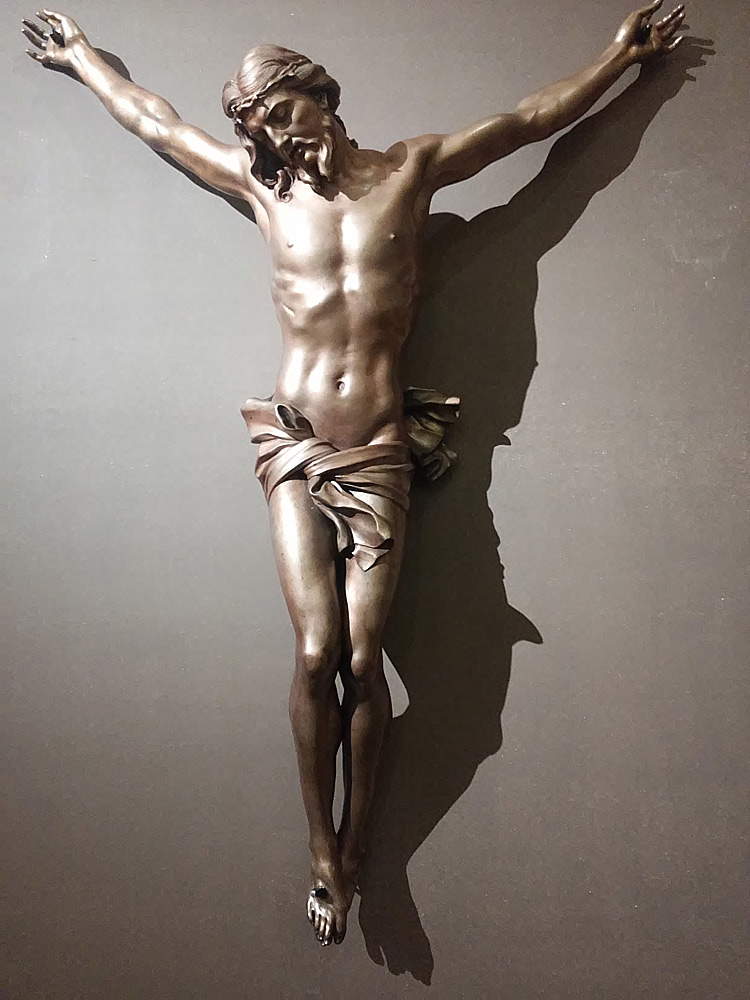

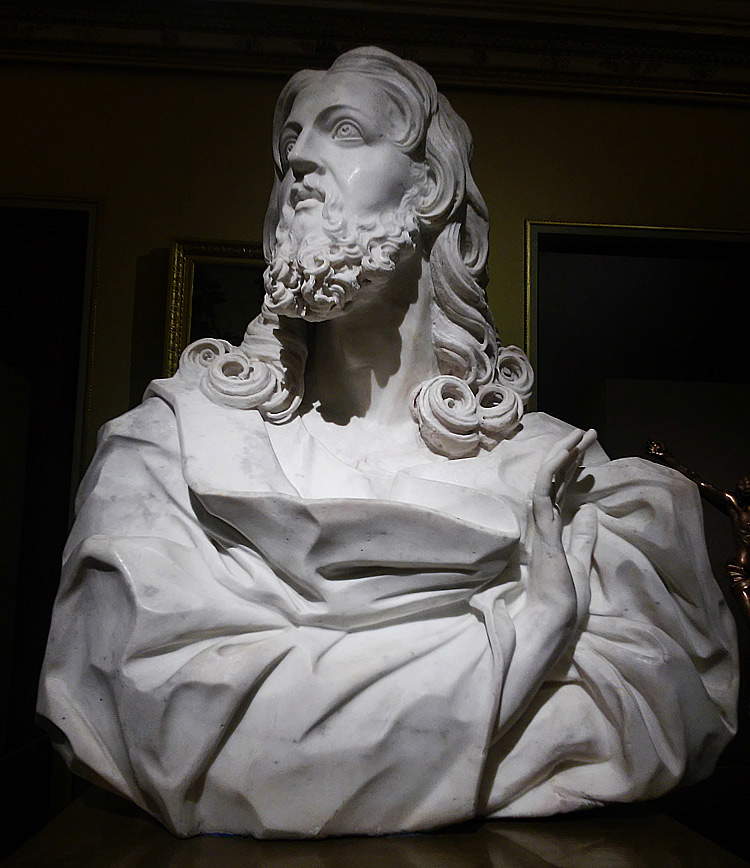

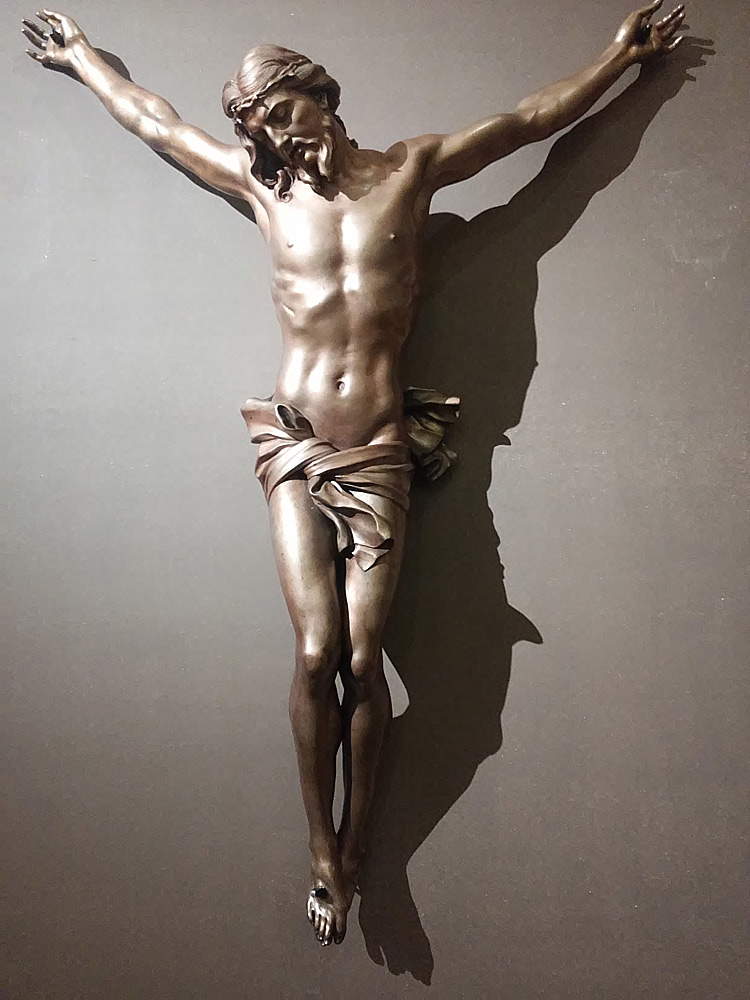

The last two rooms are those that perhaps best make us aware of the full inadequacy of the Borghese Gallery as a venue for temporary exhibitions. The Room of Helen and Paris houses the sketches and models of the Fountain of the Rivers, the only section devoted to the artist’s great public works: the works have been placed in the exact center of the room, with the result that the precious models end up disturbing the vision of the masterpieces in the room, first and foremost Domenichino’s never-too-praised Hunting of Diana. And the same is true of the Hall of Psyche, where Titian’s Amorsacro e Amor profano is almost reduced to a backdrop for the display that acquaints the public with the last Bernini. There are four works on display in this room: the two crucifixes, the one from the Escorial (1654-1657) and the bronze one from the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto (c. 1659), and the two busts of the Salvator Mundi, the one from St. Sebastian Outside the Walls and the one from Norfolk (1679). This double comparison, net of the jarring with the context that hosts it, is certainly one of the high points of the exhibition: from the comparison of the two crucifixes, the one from the Escorial, an avowed Bernini autograph, emerges as the clear winner, in comparison with the one from Toronto, which instead shows a decidedly weaker modeling, so much so that it has led some art historians to doubt Bernini’s autograph. Exhibitions, on the other hand, also serve to stage similar comparisons in order to offer scholars contributions to try to clarify particularly thorny questions: and a very thorny one is the one concerning the Salvator Mundi, since the sources speak of a Savior that the sculptor gave to Queen Christina of Sweden, and it has long been believed that this work was the Norfolk bust. The discovery in 2001 of the bust of St. Sebastian has had the effect of dividing critics between those who argue for the totally Bernini authorship of the Norfolk Savior, and those who assert the opposite: the exhibition seems to lend credence to the theory of Bernini’s authorship of the Roman bust, instead placing a question mark next to the English one.

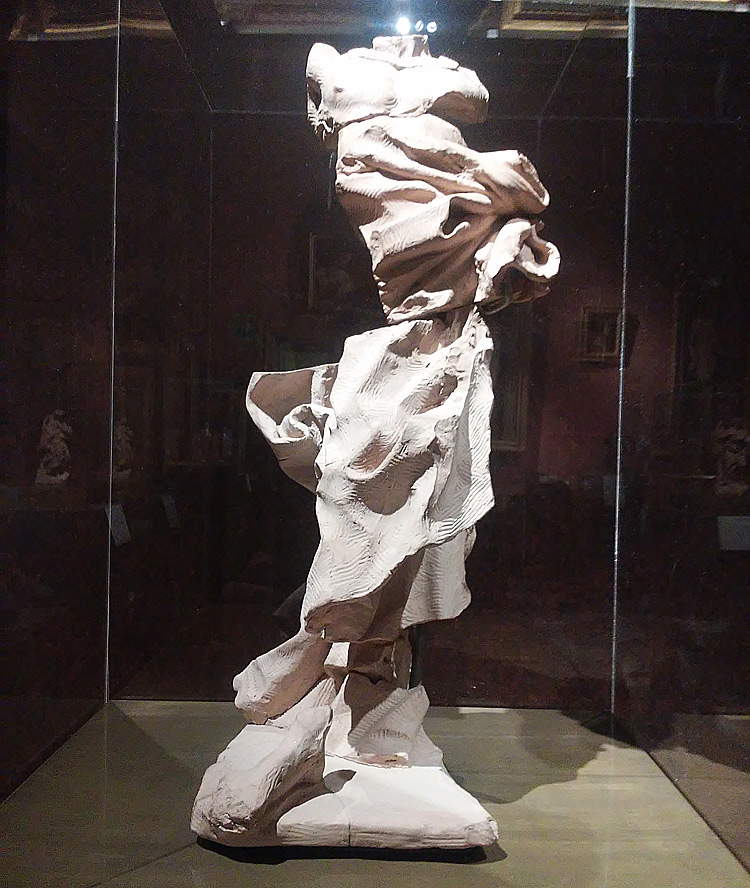

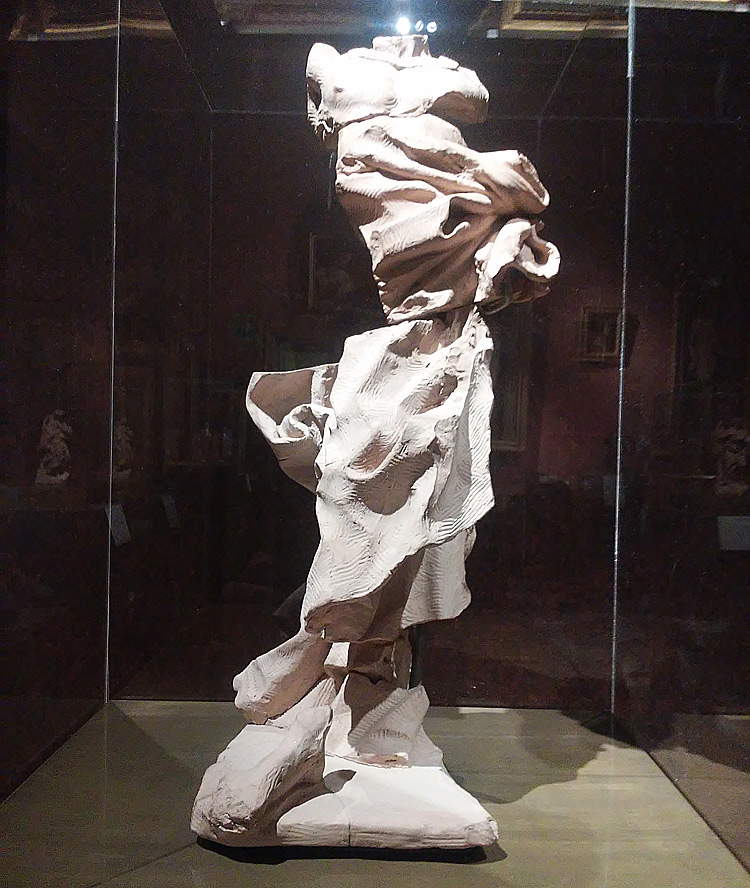

Retracing back through the rooms of the picture gallery, one can end the discussion with the Hall of Hercules, where numerous sketches find their place to illustrate to the visitor the “sculptor’s craft”: models in papier-mâché, wax, bronze, terracotta and wood were essential to fix an idea and to have a clear picture of the technical aspects to be dealt with during the execution of the finished work. “What counted above everything,” writes Maria Giulia Barberini in her essay devoted precisely to the sculptor’s craft, “was the concept, the intuition, the illuminating idea. A concept that places the ’totality and wholeness’ of Bernini’s production in the full development of the imagination resolved in forms derived from tradition to achieve fantastic innovations, or even properly technical innovations, whose goal was in any case the unity of the visual arts.” Among the models we find in the room is the one, in terracotta, for the San Longino, Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s first colossal work, which resulted from the assemblage of four different marble blocks, joined by means of pivots: the model from the Museum of Rome, with its clean cuts at the joints, shows the portions to be joined as Bernini imagined them.

|

| The Hall of Busts |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Bust of Antonio Cepparelli (1622-1623; marble, 70 with pedestal x 60.5 x 28.5 cm; Rome, Museo di Arte Sacra San Giovanni dei Fiorentini) |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Costanza Piccolomini Bonarelli (c. 1635; marble, 74.5 x 64.2 x 5 cm; Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello) |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Bust of Cardinal Armand-Jean du Plessis, Duke of Richelieu (1640-1641; marble, 83 x 70 x 32 cm; Paris, Musée du Louvre) |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s self-portrait and bust of Constance Bonarelli |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Christ Crucified (1654 - 1657; bronze, 145 x 119 x 34 cm; Madrid, Colecciones Reales, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Monasterio) |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Christ Crucified (c. 1659; bronze, 174 x 120.7 x 36.8 cm; Toronto, Art Gallery of Ontario) |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini?, Bust of the Salvator Mundi (c. 1679; marble, 96.5 x 79 x 28 cm, base 29 x 44.5 x 44.5 cm; Norfolk, Chrysler Museum of Art) |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Bust of the Salvator Mundi (1679; marble, 103 x 100 x 48.5 cm; Rome, San Sebastiano fuori le Mura) |

|

| The room dedicated to the sculptor’s craft |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Saint Longinus (1633 - 1635; terracotta model, 48.5 x 20 cm; Rome, Museo di Roma) |

The exhibition thus moves between highs (the masterpieces, some thematic insights such as the one on the youthful production and the sculptor’s craft, the busts, the comparisons in the last room) and lows (the interferences with the works in the permanent collection, the section on painting, the too-clear detachment between the rooms on the first floor and those in the picture gallery, the inconsistent passages of the itinerary, due to the conformation of the Gallery): nevertheless, it is also true that retracing Bernini’s career having at one’s disposal the heritage of the Galleria Borghese is a truly beyond interesting opportunity, especially if the itinerary can count on many of the works that are fundamental to understanding the poetics of the sublime sculptor who inaugurated the season of the Baroque, of the great virtuoso who helped to define the profile of Rome forever, of the illustrious sculptor whom Maffeo Barberini described as “a rare man, sublime wit, and born by divine disposition, and for the glory of Rome to bring light to the century.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.