When and how the history of contemporary art begins is a question with not a few ambiguities. In academia, according to rather widespread conventions, it is made to coincide with historiographical periodizations that situate the origins of the contemporary era with the French Revolution. Thinking, however, of a painting such as Jacques-Louis David’s Assassinated Marat in the same temporal partition as Duchamp’sUrinal or even Cattelan’s Ninth Hour raises more than one doubt. For this reason, this ordering is not infrequently criticized, and various reorganizations are proposed from time to time. There are those who would like to date contemporary art to the mid-19th century with the appearance of Courbet and the realists, while some prefer to wait for the entry of the Impressionist movement. Still others, perhaps more convincingly, such as Renato Barilli, see in the French compage a continuity with earlier artistic movements and lean toward recognizing in Cézanne the father of the contemporary, and in the Avant-garde the children who first climbed this road. Following this theory, it is therefore the 20th century that greets contemporary art (with the exception of Cézanne, who moves alone in the decades before), an instance that does not arise “by evolutionary way from thenineteenth-century art,” as Mario De Micheli argued, but on the contrary “from a rupture of nineteenth-century values,” thus ending the process of artistic progression baptized by the famous Vasarian parable.

In fact, according to Argan, the Avant-Garde is a movement that invests art with an ideological interest and “prepares and announces a radical upheaval of culture and custom, denying en bloc the whole of the past and replacing methodical research with bold experimentation in the stylistic and technical order.” It could be objected, and with good reason, that even in the term “avant-garde” a certain ambiguity is inherent, for while it is true that some of the movements that comprise it stand out, at least in their declarations, in open contrast to the art that preceded them, no one could help but build on previous experiences, albeit in different forms and measures. Nevertheless, the deliberate conflictuality that these artists flaunt against canons and conventions, and the obstinacy and inordinate prolificacy with which they experiment with new modes of expression, characterize those movements that in the first decades of the 20th century decided to wage a battle “on the front lines,” earning the role of innovators and pointing a way forward that would have gigantic repercussions for all art to come. And it is in Pisa, at the Palazzo Blu, that the works of some of those protagonists are on display from September 28 until April 7, 2024 at the exhibition The Avant-Garde. Masterpieces from the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

In fact, just over forty works, mostly paintings, have arrived from the important museum in the United States, the austere neoclassical temple that boasts a collection of more than 225,000 pieces, more than 12,000 of which are on display. This institution dominates the American metropolis from the top of that staircase that has also become iconic thanks to the famous Rocky Balboa films. The boxer himself at the end of Chapter V of the saga pushes his way inside the museum he had ignored until then, thanks to his son’s exhortations, “it’s never too late to learn, you’ll see Picasso you’ll like.” It is precisely with Self-Portrait with Palette by the Spanish painter that the experience of visiting Pisa begins, which is attested as a strictly chronological itinerary.

The work, created in 1906, stands as an explicit homage to Paul Cézanne; in fact, it was painted shortly after the Aix-en-Provence master’s death on Oct. 23, moreover confronting one of his paintings with the same theme, as if to externalize Pablo Picasso ’s desire to make himself heir to his experience. The formal synthesis of the painting benefits the exaltation of the monumentality of the figure, denoting compositional solutions also inferred from primitive art, in a direction that would shortly thereafter be declined in its most accomplished expression in the symbolic painting that baptizes the Cubist movement, Les demoiselles d’Avignon.

TheCubist adventure is undoubtedly the one most represented by the pieces in the exhibition, and perhaps the only one in a satisfactory way, although there is no intent to periodize or analyze it. It ranges from its application in a barely hinted direction, as in the still perspective architecture of the Gothic church in Robert Delaunay’s painting Saint-Séverin , or in that rather pandering compromise of Jean Metzinger in TheTea Hour, which was not surprisingly hailed as the “Mona Lisa of Cubism,” since the solid female figure is clearly recognizable, thus smoothing the public’s taste. Continuing on we find far more orthodox paintings, including Picasso’s Man with Violin , which already shows some of the most extreme declinations of analytical Cubism, where the human figure is barely recognizable, deconstructed in countless sections; and Basket of Fish by Georges Braque, theartist who most along with the Spaniard experimented with the scope of action of Cubism, who in this still life presents the subject as multifaceted in multiple visions, while lights and shadows are distributed without the pursuit of any naturalism, but rather moving toward an abstract treatment. Instead, the complexity of geometries thins out and the palette becomes increasingly brilliant in Juan Gris’ essays, while decomposed volumes become sculpture, in Lithuanian Jacques Lipchitz’s bronzes.

The sap of cubism also served to fuel operations, which departed from the icy analytical bent, as in Marchel Duchamp’s painting Yvonne and Magdeleine Reduced to Tatters . The painter, among the leading figures of Dada art and among the most influential artists in history, made use of Cubist decomposition to fragment the image of the sisters, in a painting that nonetheless becomes grotesque and caricatured, ahead of certain Surrealist outcomes. But then again, the brilliant French painter throughout his life was a forerunner of the times, and soin the Portrait of Gustave Candel’s Mother painted between 1911-12, he outlined with realistic flair the top of an old woman’s face and body grafted onto a pedestal, in a work that is certainly expressionist, but which already seems to know the famous mannequins of metaphysics and that taste for nonsense of surrealism. The Chocolate Grinder (n1), painted in 1913, shows a pictorial essay in icy technicality, almost as if it were a mechanical design, illustrating the instrument that caught the artist’s eye in the window of a pastry shop; in thework he also wanted to include a pre-printed leather insert with the title of the machine, thus giving rise to an early experimentation of those ready-mades, intrusion into the world of art of real objects which without undergoing any modification claimed the title of masterpieces, which would forever change the course of art history.

After the acme one encounters with Duchamp’s paintings it all seems a bit more tepid: don’t get us wrong, there are other masterpieces, but they are still more stereotypical works, where certainly one recognizes the more typical avant-garde figure, but nothing particularly surprising. And even the aseptic organization of the rooms does not seem to enhance them much. Perhaps the most interesting confrontation is consumed in the small section “Millenary Traditions or Revolutionary Novelties?” where Marc Chagall ’s painting Purim with references to Jewish culture but also to Russian folk traditions is counterpointed by Fernand Léger’s The Typographer: a hymn not only to the modernity of the working world, but also of painting, still unabashedly cubist, and of graphics.

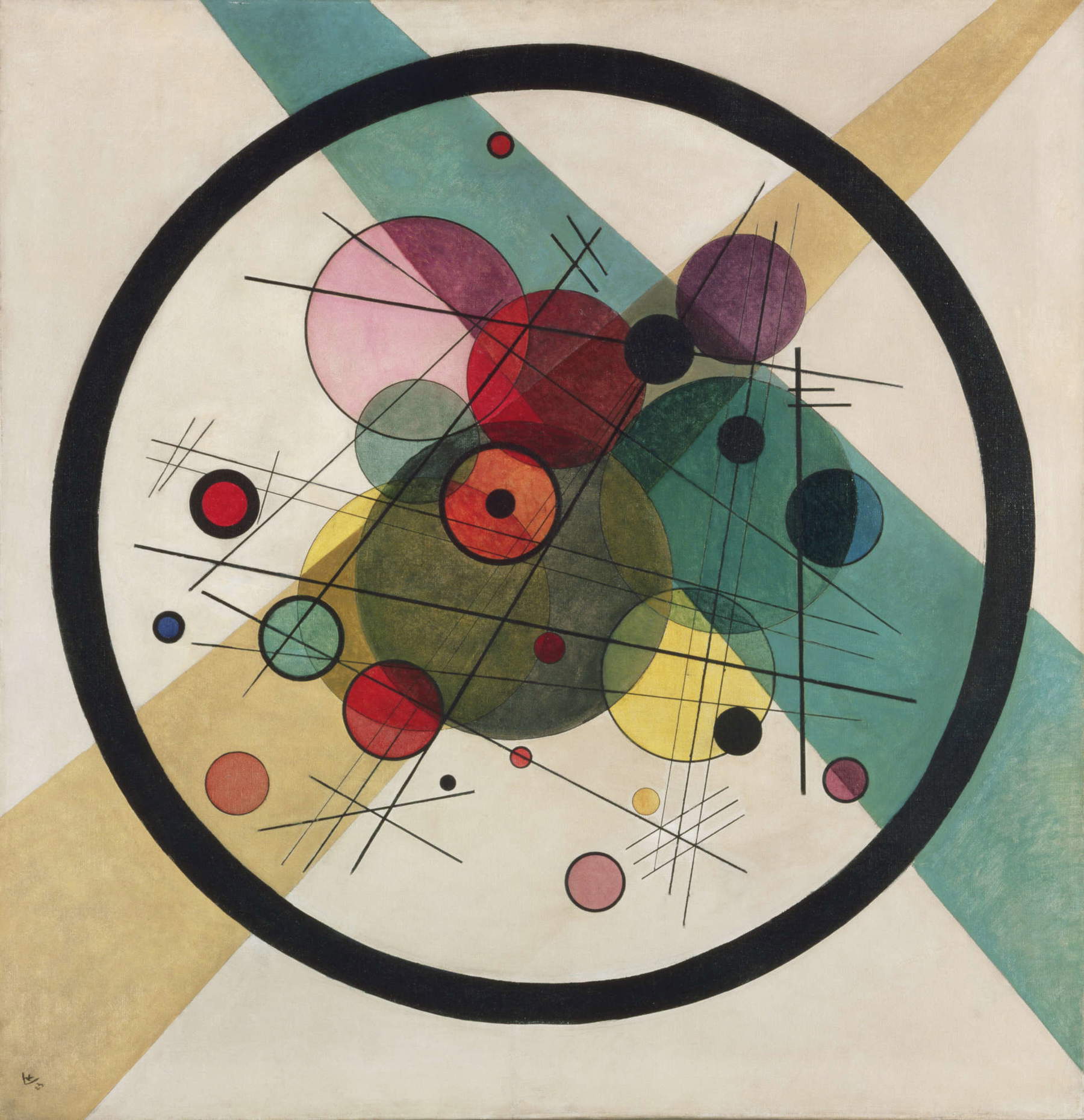

The next chapter of the exhibition presents the quests towardabstraction, and the sparse room is dominated by Kandinsky’s Circles in a Circle, a work of which the Russian painter himself wrote, “it is the first painting of mine to bring the theme of circles to the fore.” Here, a galaxy of shapes and colors interact in a lyrical composition. Also in this section are Alexej von Jawlensky ’s beautiful heads, where through color and a few graphic signs, the painter probes the spiritual drifts of painting; there is also a painting poised between futurism and cubism by Lyonel Feininger and a painting by Léger, which the dogmatic chronological arrangement has arranged here, even though it has very little that is abstract. And it is only chronology that validates the next section that places Max Ernst and his Surrealist works next to the fairy-tale paintings of Marie Laurencin and the poetic compositions bathed in warm Mediterranean light by Henri Matisse, in any case among the most beautiful paintings in the exhibition.

On the upper floor, the selection of the Surrealists, the ensemble that opened the door of the unconscious and the oneiric to art, is anticipated by that devourer of contemporary art that is Picasso, the artist who succeeded throughout his life in harnessing diverse influences into a highly personal vision, always achieving surprising results, as in Bather, a project for a monument. In this canvas the Spaniard associates random objects, responding to Surrealist poetics, but with forms still mindful of Cubism. Among the Surrealists, the last true Avant-Garde of the early 20th century, the exhibition includes Joan Miró, with his imaginative alphabets; the primal energies eternalized by Paul Klee, André Masson and Hans Arp, who evoke biomorphic figures, such as those that also populate Yves Tanguy’s almost seabed-like universe, and are reminiscent of Bosch. Intrusions, however, include the usual Braque and Jean Hélion’s geometric abstractions.

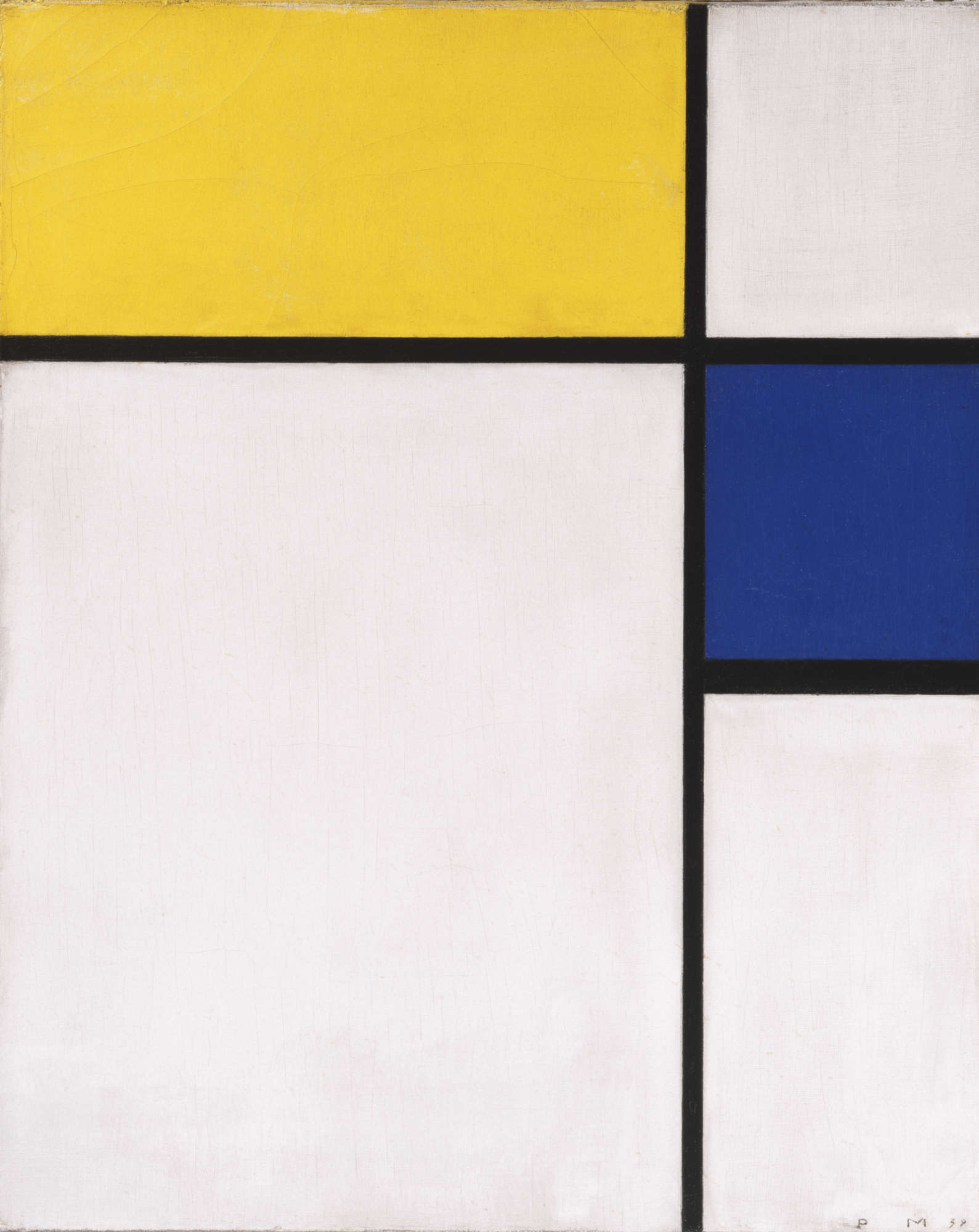

The works that conclude the exhibition are those created in the years leading up to World War II, with which the experience of the Avant-gardes practically came to an end. They include two compositions by Piet Mondrian, the artist who founded the current of the Neo-Plastic style, by which he freed painting from any element related to the natural world, building his works on three pivotal elements: line, plane and color (limited to primary and neutral ones). His works aspire toward a continuous search for balance, almost as if the painter found the specific weight of each color and managed to balance it in his solid lines. “Doesn’t a blue weigh twice as much as a yellow?” the painter seems to suggest. It should be noted, unfortunately, that the strength of his works today is somewhat compromised when viewed up close, as the compactness of his whites especially, but also of his other colors, has faded, the pigment as it has aged has discolored and graying, and the texture of the support emerges, in effect altering those minute proportions that had so engaged the Dutch painter.

The last two works we find are a sculpture by Lipchitz, no longer cubist but seemingly indebted to Picasso’s famous painting Two Women Running on the Beach, and a crucifix by Chagall. The two Jewish artists, and with them so many others, were forced to flee the atrocities of Nazism, scattering some of Europe’s best energies, and soon changing the coordinates of art, which saw its epicenter shift from Paris to New York, thus decreeing the fortunes of art overseas.

The Palazzo Blu exhibition stands as an admittedly enjoyable event but one that does not hold a candle to the last major exhibitions the Pisan institution has ringed up. The selection of works certainly does not prove to be sufficient to exhaust such a complex discourse as that of the Avant-gardes, which is in fact monolithic, deprived of some of the most interesting experiences, such as Futurism and Dada to give an example. Moreover, the strict chronological criterion combined with the desire, however, to divide the sections by artistic movements brings out these shortcomings and highlights some inexplicable simplifications. It might have been better to break free from the chronological order and instead construct thematic nuclei as happens, for example, in the comparison between Chagall and Léger alone.

On the other hand, it should be positively reported, that this time, the visiting space that is offered to the visitor is more pleasant than usual, since the intricate and not wide spaces of the Pisan palace are less cluttered, with a sparse set-up curated by Cesare and Carlotta Mari, and make the display of the works pleasant, also enhanced by the graphic choices that connote the sections, lively but tasteful. In short, an exhibition that we certainly don’t regret having seen, thanks in part to a dozen absolute masterpieces, but in case we missed it, perhaps we wouldn’t have great regrets.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.