by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 29/03/2017

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'Arturo Dazzi. 1881 - 1966' in Rome, Villa Torlonia; Carrara, Centro Arti Plastiche; Forte dei Marmi, Villa Bertelli.

It should not move one to wonder that the figure of one of the greatest artists of his time such as Arturo Dazzi (Carrara, 1881 - Pisa, 1966) is today almost unknown, and even in his hometown low is the number of those who are able to enumerate some of his works, other than the Cavallino in the version that proudly displays itself in Piazza Matteotti, one of Carrara’s main squares. The point is that Dazzi compromised with fascism. We do not know if (and possibly how much) convincingly, partly because his shy and reserved character kept him away from blatant “professions of faith,” but the magniloquent and often rhetorical charge of his art, which was well suited to embodying the myths of the regime (and in fact he often lent himself to this end), was enough to inflict on him that damnatio memoriae shared with other great names of the time: just think of artists such as Giuseppe Terragni or Achille Funi, similarly forgotten by most. Thus, to raise the figure of Dazzi from oblivion, an exhibition intervened this year, entitled simply Arturo Dazzi. 1881 - 1966, designed to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the artist’s death and curated by Anna Vittoria Laghi, which stopped in what we can consider Arturo Dazzi’s three cities: Rome, where the sculptor’s monumental emphasis was expressed in the works commissioned from him by the fascist regime (and where, at the end of January, the first stage, which started in October, ended at the Casino dei Principi of Villa Torlonia); his native Carrara, which at the Plastic Arts Center is hosting the second stage until April 30; and Forte dei Marmi, a place of retreat that inspired Dazzi’s most intimate and delicate works (the third and final stage will be held at Villa Bertelli).

The main merit of the exhibition, strengthened by an itinerary reconstructed with philological rigor and availing itself of loans mostly from the Dazzi Donation of Forte dei Marmi (the fund that his wife donated to the town of Versilia after the artist’s death), is precisely that of bringing out the dual soul of Arturo Dazzi’s art. On the one hand, the celebratory sculptor who emphatically gave shape to the artistic feats desired by Mussolini: the processes that led to the realization of some of his greatest monuments (“great” also literally: they were often sculptures of enormous proportions) are documented thanks to the presence of sketches, studies, and period articles. On the other, the artist who in the painting practiced especially during his rest periods in Versilia was able to find a more meditative, calmer dimension, far from the politics and rhetoric of the regime, but also from the weather: beaches, landscapes, peasant women, herdsmen become the protagonists of a painting that starting roughly in 1935, writes the curator in the catalog, “becomes a moment of escape and distances itself from sculpture,” except when it gets closer to the latter at the moment when sculpture, too, becomes “freer than the official one,” paradoxically “when the conditioning of the regime has become stronger.” One senses, in other words, a divergence between the official sculptor who continues to receive commissions designed to glorify fascism, and the private sculptor who, on the contrary, recovers a humanity that had already manifested itself in some of his youthful works but had been somewhat overwhelmed by the pompous heroism of public achievements.

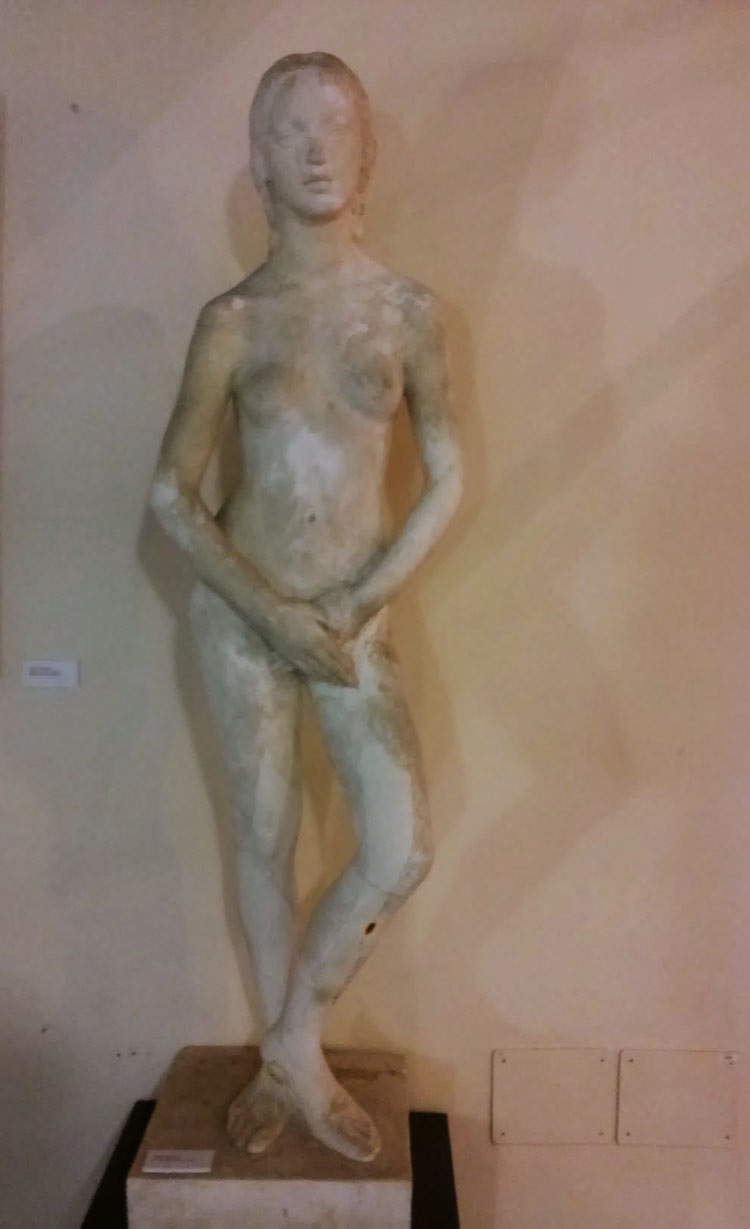

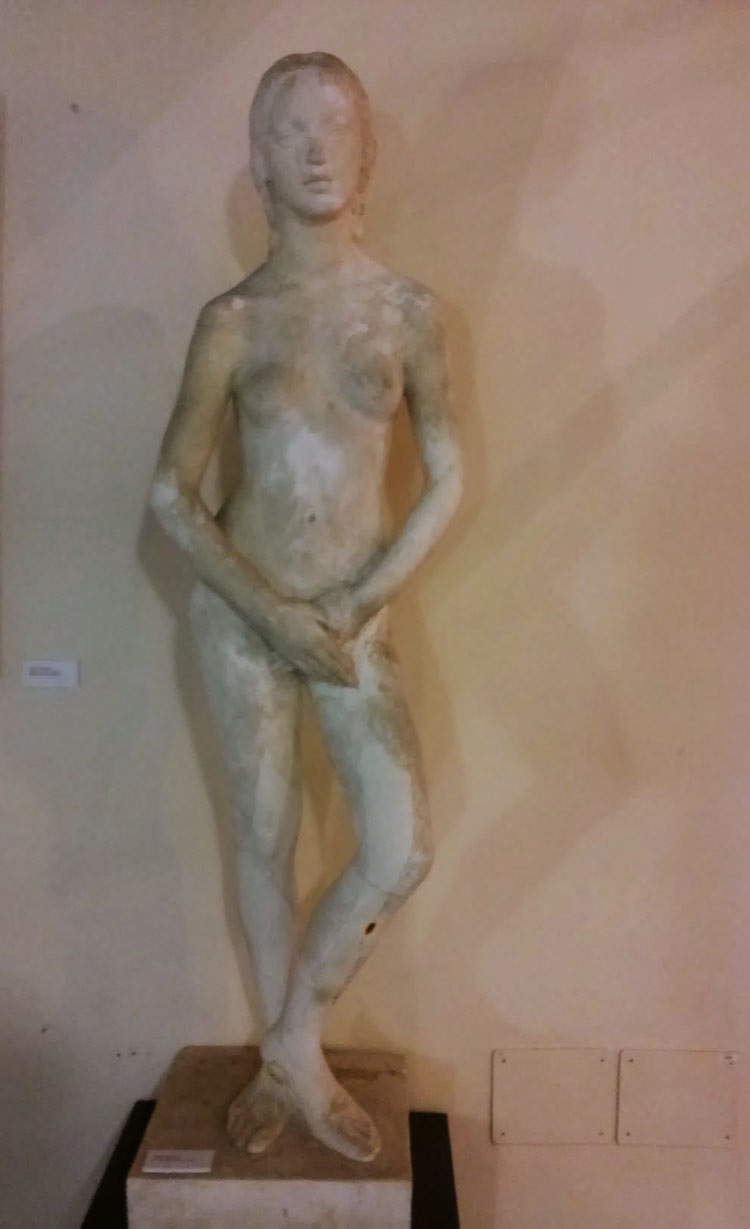

And it is no coincidence that the itinerary opens (albeit somewhat unhappily, since the work is located at the very end of the staircase leading to the second floor and the correct view is sacrificed) with theAdolescent of 1935, a sculpture that perhaps better than any other makes clear this caesura of which the exhibition intends to account. The aim is to operate a recovery of the artist’s memory, demonstrating that Dazzi was a complex artist, and allowing the message to seep out that the judgment that still rejects the sculptor from Carrara, nailing him to his propaganda-like production, must be overcome, leaving room for an overall evaluation of an art that, when it was capable of acquiring a dimension of its own, revealed an “intense and poetic” artist, discoverer of “unprecedented, intense intonations, full of symbolic and spiritual meanings.” That Dazzi was a refined, humane and talented artist is evident from his earliest achievements, including an early Portrait of Clara signed and dated 1900 (thus a year before his move to Rome): grace and Art Nouveau elegance mark the beginnings of a sculptor who, in the years to come, would come closer and closer to an intense realism in line with the research of those artists who, like Dazzi, were active on the Roman scene and intended to break away from the avant-garde (and, at the same time, from academicism) in order to propose an art that was able to latch on to the Italian tradition (names such as Nicola D’Antino, Giovanni Prini, Publio Morbiducci and, in general, all the artists who adhered to the so-called “Roman Secession,” in the exhibitions of which Dazzi himself also participated, could be cited as examples). The sculptor from Carrara was appreciated precisely because, from the end of World War I onward, the climate of “return to order” sanctioned the new orientations of the taste of the time, and his works responded well to the renewed demands. Thus we find in the first room of the exhibition (the best set up, in the opinion of the writer) touching works such as the Ritratto di Bimbo (Portrait of a Child ) of 1920, particularly illustrative of the trend of these years that saw figures emerge from an undefined background, like the Serafina with which the sculptor participated in the 1920 Venice Biennale, and again that splendid Sogno di bimba (Dream of a Little Girl ) that had impressed an artist like Carlo Carrà to the point of leading him to consider Dazzi as a “new Bartolini.”

|

| Arturo Dazzi, Adolescent (1935; plaster, 169 x 48 x 60 cm; Forte dei Marmi, Dazzi Donation) |

|

| Arturo Dazzi, Portrait of a Child (ca. 1920; marble, 66 x 44 x 30 cm; Brescia, Galleria dell’Incisione) |

|

| Arturo Dazzi, Serafina (1920; marble, 68 x 36 x 34 cm; San Marcello Pistoiese, Andrea Dazzi Collection) |

|

| Arturo Dazzi, Dream of a Little Girl (1926; plaster block cast, 37 x 121 x 54 cm; Forte dei Marmi, Dazzi Donation) |

A work that acts as a “link” between the first section of the exhibition and the following ones, as well as between the first phase of Arturo Dazzi’s career and the following ones, is the aforementioned Cavallino, present in the exhibition in its original plaster model preserved in Forte dei Marmi. Suggestive is the layout aimed at offering a minimal reconstruction of the artist’satelier around one of the key works in Dazzi’s career, first presented at the Venice Biennale in 1928 in a wax version: the foal that, as Carrà wrote, the sculptor “was slowly building up, with a patience of an ancient craftsman, compass in hand, but not so much for the objectivity of the proportions, as to give certain structure to that restless image of life that lay before him,” was one of Dazzi’s most successful works. In this sculpture, characterized by a lively naturalism, lives that disagreement between monumentality and delicacy, here particularly evident when one compares the animal’s almost haughty pose with its young age, which invariably dilutes its pride. The theme of the animal in art was, moreover, explored by Dazzi in 1930, on the occasion of a Roman exhibition that was entitled L’animale nell’arte and in which the artist participated with four sculptures and six paintings. The current exhibition brings together a large selection of what Dazzi made for the occasion: we can identify the culminating moments in the profound compassion of the Dying Fawn and the in-depth study of Gazelles, which led the curator to establish a comparison between Arturo Dazzi’s realism and that of Gustave Courbet, who in the milieu was after all considered the true initiator of modern art.

|

| Arturo Dazzi, Cavallino (1928; original plaster model, 155 x 90 x 44 cm; Forte dei Marmi, Dazzi Donation) |

|

| The room with animals from the 1930 exhibition (on the wall, left, Gazelles and on the floor, center, Dying Fawn. |

A plaster model for theTriumphal Arch of the Fallen in Genoa, a relief in which Dazzi portrays himself together with another of the most representative artists of the twenty-year Fascist period, namely Marcello Piacentini (who designed the structure of the monument: Dazzi was instead responsible for the decorative frieze), is responsible for introducing the section devoted to monumental sculpture. In fact, compared to the numerous commissions Dazzi received from the regime (the various war memorials, the statues for the Cadorna Mausoleum in Pallanza, the San Sebatiano for the Casa dei Mutilati in Rome, designed moreover by Piacentini, and again the famous Era Fascista in Brescia, the Mausoleum of Costanzo Ciano later left unfinished, the Victory in Forte dei Marmi, and many others), the exhibition includes examples documenting only two monumental works assigned to him during the 20-year period, namely the aforementioned Arco di Genova and the Stele Marconiana (begun in 1937 but finished 20 years later), to which must be added two panels for St. Peter’s Gate (Dazzi won the competition for the basilica’s bronze doors, which was announced in the immediate postwar period, but was later excluded: this was the only defeat in the artist’s career).

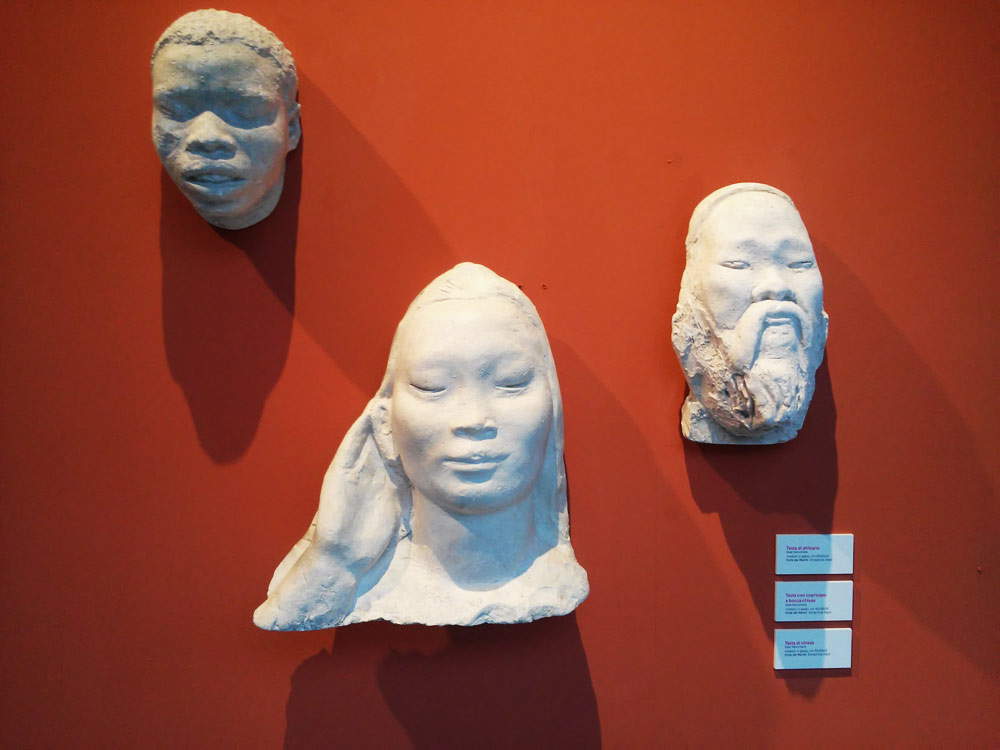

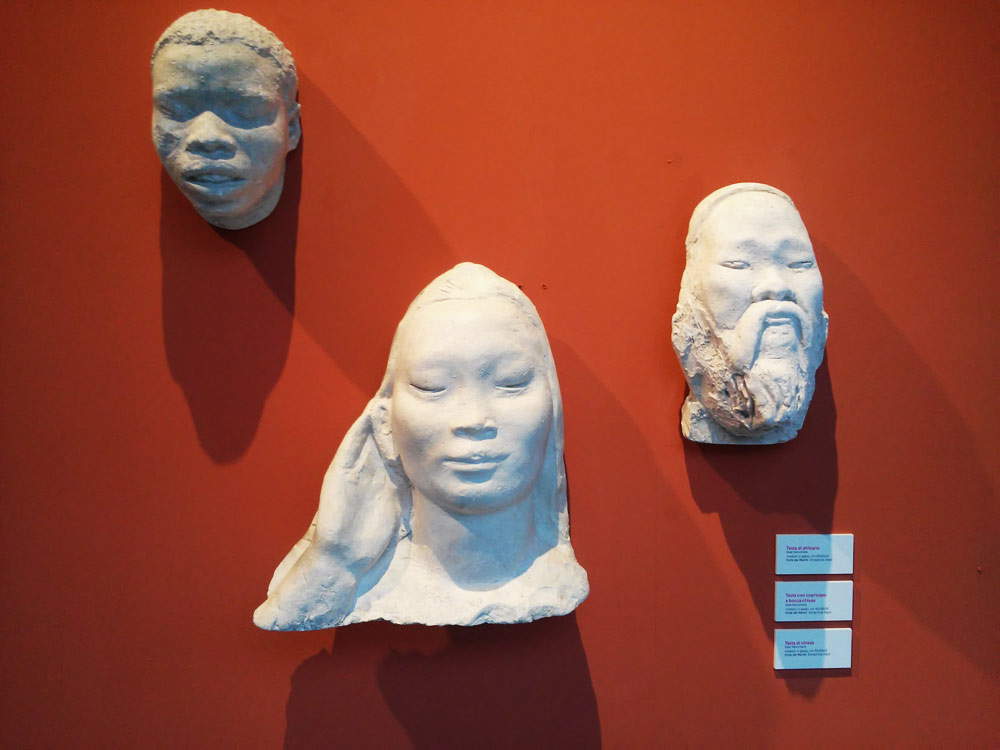

And if for the Genoa Arch there are only the above relief and articles from the time (in which the work is extolled as “the monument that the sons of the Superb wished to erect, as a tribute of love, to the memory of their fallen in war and as an eternal consecration of victory”), more space is accorded to the obelisk in Rome’s Eur, which, with its shape vaguely resembling that of an antenna, celebrates the inventor of the telegraph, Guglielmo Marconi, as well as his invention, through an articulate iconographic program. The Carrara exhibition does not give an account of all the allegories that make up the stele’s narrative (which, with its archaic classicism, openly refers to Trajan’s Column), but it dwells, for example, on some heads belonging to people from different populations that were meant to convey the idea of the universality of the radio medium, capable of bringing all the peoples of the world together and uniting them in a brotherly embrace. It is worth noting that Dazzi stopped working on the stele in 1942, and resumed it some time after the end of World War II, at the interest of Marconi’s descendants: we know that he destroyed all the original sketches, and it is quite likely that the atrocities of the conflict had prompted him to drastically rethink his monument. This is yet another curatorial choice aimed at rehabilitating Dazzi’s memory: the visitor cannot fail to notice that the exhibition leans in favor of the private and anti-rhetorical Dazzi, as is only natural for an exhibition that intends to revise the judgment on the artist.

|

| Arturo Dazzi, Dazzi and Piacentini, detail of Triumphal Arch of the Fallen in Genoa (1923-1931; original plaster model, 100 x 61 x 23 cm; Forte dei Marmi, Dazzi Donation) |

|

| Arturo Dazzi, Head of African, Head with Closed Mouth Headgear and Head of Chinese for the Marconi Stele (plaster models, 26 x 15 x 16 cm, 40 x 36 x 30 cm and 32 x 20 x 15 cm, respectively; Forte dei Marmi, Dazzi Foundation) |

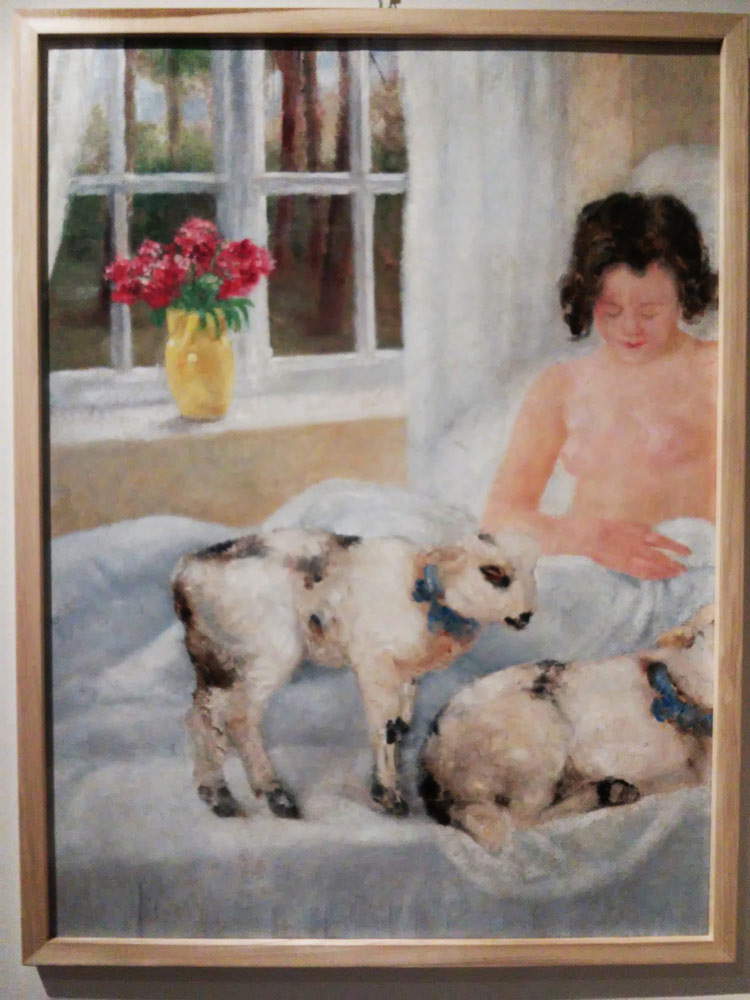

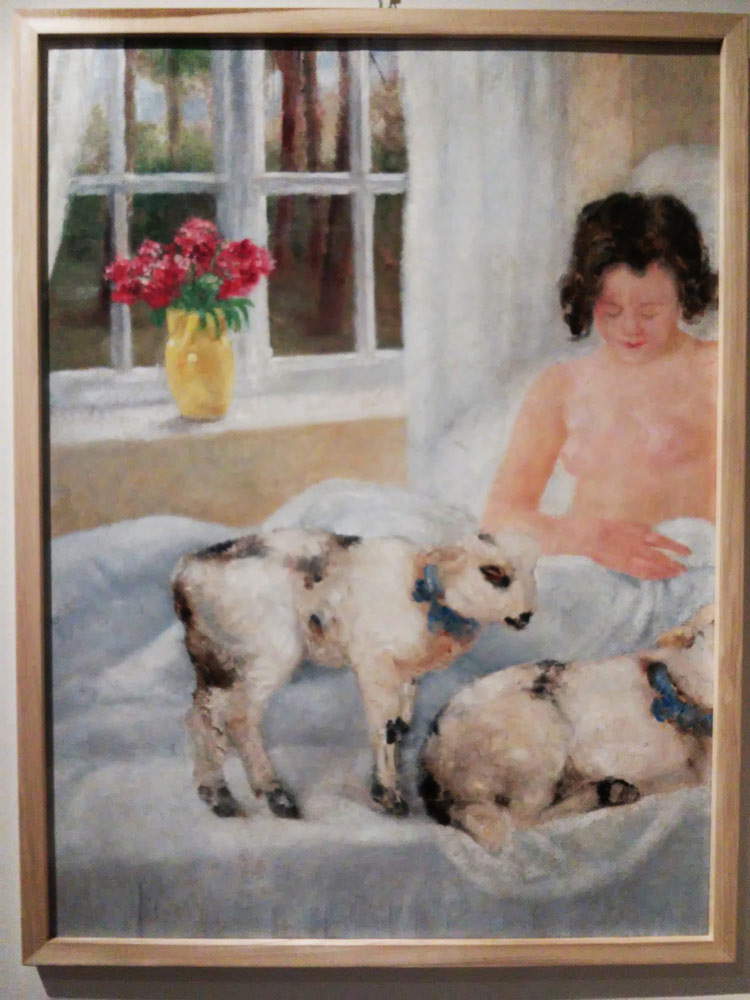

The paradigm shift in Dazzi’s art is exemplified in the next room by an interesting comparison between the 1936Agnellino, designed for the Agnelli Chapel, and the Ritratto di bimba con agnellini painted a year earlier: the correspondence between the two forms of expression practiced by Dazzi, painting and sculpture, is in this portion of the exhibition aimed at making evident the peculiar poetics of the affections that allowed the artist to achieve that “free and spontaneous expression” (so again Anna Vittoria Laghi in the catalog) that constituted the main feature of his painting from 1935 onward. However, there was no lack of prodromes in earlier years: two intense paintings, made in the two-year period 1931-1932, such as Boat on the Beach, a melancholy and misty “end-of-summer” piece on the coast of Marina di Carrara, and the equally evocative After the Rain, with its somber light that gives us the vivid impression of standing in front of a window overlooking a glimpse of Versilia just crossed by a thunderstorm, are admirable essays of Arturo Dazzi’s fine landscape skills, who would return to “reflective” themes on several occasions, far from clamor and officialdom. Not least because it was Arturo Dazzi himself who moved away: the “sweet Versilia that made me a painter” (this is how he described his adopted land) became the workshop where the artist experimented with the most collected solutions of his production.

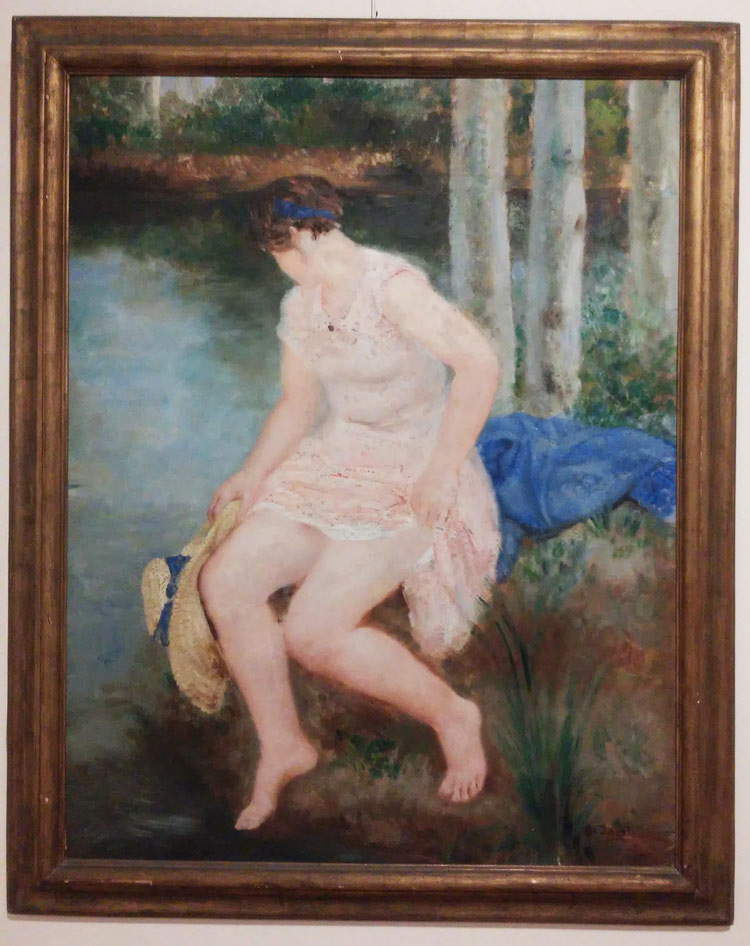

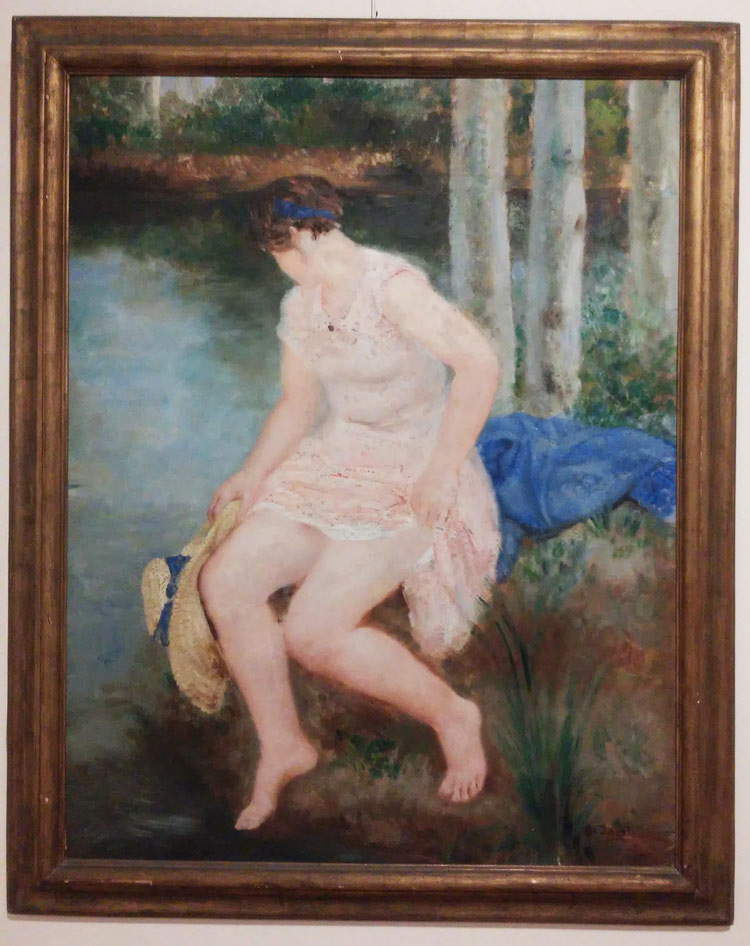

These were paintings made en plein air, endowed with a spontaneity the artist could only achieve by painting in the open air: “a nude of a young girl on the seashore or in the shade of poplars moves me more than if it were enclosed within four walls,” he wrote, presenting himself at the 1935 Quadriennale in Rome with no less than twenty works (nineteen paintings and one sculpture). Some are on display in the exhibition: suffice it to mention the voluptuous Giovinetta, a nude that, like the bather in Sul fiume in Versilia, reveals an unexpected impressionisticapproach, capable of conveying, quoting again from the catalog, “values of a painting that increasingly moves away from the ’true’,” where by “true” we mean a realism strictly adhering to the natural datum, “to express a more intense and participated feeling.” These are the researches that anticipate thelast Dazzi, to whom the concluding section of the exhibition is dedicated.

|

| Arturo Dazzi, Child with Little Lambs (ca. 1935; oil on plywood, 123 x 93 cm; Forte dei Marmi, Dazzi Donation) |

|

| Arturo Dazzi, Little Lamb (ca. 1936; plaster, 65 x 41 x 48 cm; Forte dei Marmi, Donazione Dazzi) |

|

| Arturo Dazzi, Boat on the Beach (c. 1932; oil on plywood, 72 x 81.5 cm; Forte dei Marmi, Donazione Dazzi) |

|

| Arturo Dazzi, After the Rain (1932; oil on cardboard, 68 x 91 cm; Private Collection) |

|

| The room with the works created in Versilia |

|

| Arturo Dazzi, Giovinetta (1935; oil on faesite, 144 x 83.5 cm; Carrara, Cassa di Risparmio) |

|

| Arturo Dazzi, On the River in Versilia (1935; oil on plywood, 156 x 122 cm; Carrara, Academy of Fine Arts) |

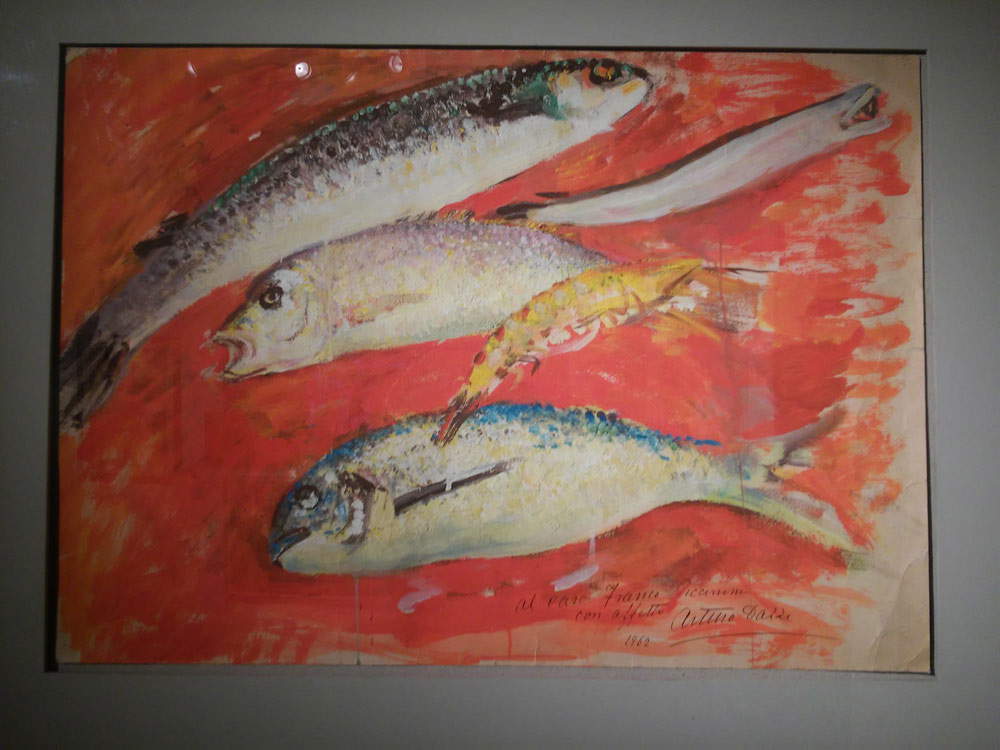

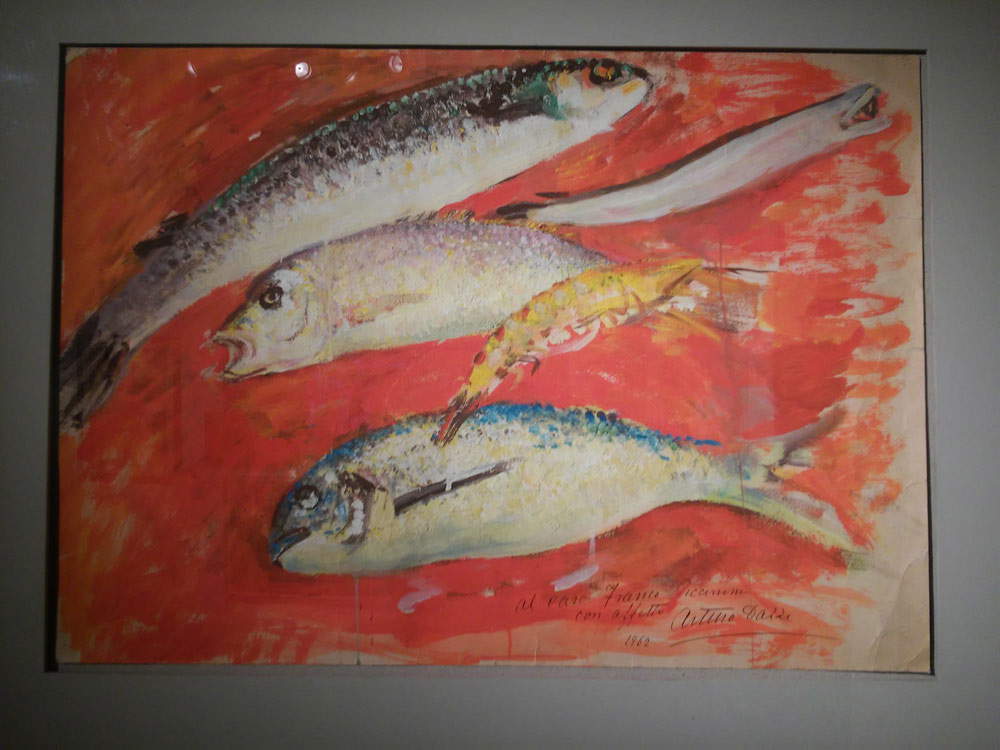

The works, beginning in the 1950s, become populated with delicate, almost lyrical images, and this applies to paintings as well as sculptures. Fish that become the favorite subject matter of Dazzi’s art in the context of copious still lifes, more or less stylized birds caught as they hover in the air or wander over the ground, oxen and grazing horses go to replenish the roster of favorite subjects of the artist, who in the last period of his long career proved to be as close to nature as ever: they are works endowed with a great immediacy, they are sculptural paintings, where there is no particular study of perspective and where the sense of depth is uniquely suggested by the superimposition of the elements, they are images that accompany along the extreme stages of his career an artist who not even for a moment lost the will to try to renew himself.

|

| Arturo Dazzi, Fish with Shells (1955; oil on paper, 48 x 66 cm; Private Collection) |

|

| Arturo Dazzi, Birds with Fruit (tempera on faesite, 99 x 117 cm; Carrara, Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio) |

|

| Arturo Dazzi, Sepia (ca. 1960; oil on paper, 35 x 50 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Arturo Dazzi, Fish on a Red Background (1962; oil on paper, 50 x 70 cm; Private Collection) |

Arturo Dazzi is then an artist who may not meet the taste of many (perhaps that of most), and the aim of the exhibition is certainly not that (particularly in vogue nowadays) of presenting the protagonist of the review by winking at the public or, even worse, by divesting his art of some of the traits that might make it more indigestible (and consequently underestimating the public itself). None of this. There is no attempt to whitewash his art, presenting it for what it was not: clear, however, is the distinction between an official Dazzi and a more poetic Dazzi (with a clear leaning, as already reiterated, toward the latter), and the whole thing is told extremely honestly and even with a certain amount of detail, although the path is stronger and less obstructive in the first few rooms: one senses a bit of confusion toward the end, but the overall discourse does not suffer (at Villa Torlonia the works from the 1935 Quadrennial were included before the part on monumental sculpture: linearity was preferred, but one must also take into account that the spaces of the CAP in Carrara are different, and were in any case well exploited). There is no hiding the fact that Dazzi had been a regime artist. There is no silence about his relations with Fascism, despite the fact that the exhibition avoids any in-depth study of the subject: but one objection could be made, namely that the public Dazzi is well known (as well as decidedly repetitive), so it would have made little sense to dwell on a subject that would have overstepped the boundaries delineated so clearly by the layout of the exhibition. It is, in essence, an entirely new monograph. We would have welcomed some more reflection on the historical context, also due to the fact that Dazzi’s career was very long and crossed, in fact, different eras, and the operation of historical collocation of the figure is therefore rather cumbersome. There is also a good section on portraiture in the exhibition, which would have offered an excellent foothold in this sense: too bad that in the end it turns out to be the weakest and most superficial of the whole project. In conclusion, we can speak of an exhibition that, despite some aspects that can be improved and despite the fact that it may be particularly challenging, is certainly to be appreciated, especially for the accuracy of the scholarly project and the ability to establish a very articulate discourse on Arturo Dazzi, and certainly for its willingness to offer a completely unbiased and absolutely unprejudiced reading of his vast production.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.