Artemisia Gentileschi in Naples: here's what the exhibition on the artist's Neapolitan period looks like

The Gallerie d’Italia in Naples has inaugurated the exhibition history of the new venue of Palazzo del Banco, in the central Via Toledo, with an exhibition dedicated to the Neapolitan period of Artemisia Gentileschi, which thus focuses on the works that the painter created in the city between 1630 and 1654, years of her last production that have been little investigated so far. Artemisia Gentileschi in Naples, this is the title of the exhibition, is proposed as a continuation of the first monographic exhibition in the United Kingdom that the National Gallery in London dedicated in 2020 to Artemisia, illustrating the artist’s production from her Roman beginnings to her last Neapolitan period and giving particular emphasis to theSelf-Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria acquired by the London museum in 2018. Thanks to the collaboration between the National Gallery and the Gallerie d’Italia and thanks to Gabriele Finaldi as special advisor, the exhibition in via Toledo, curated by Antonio Ernesto Denunzio and Giuseppe Porzio, aims to resume the narrative of Artemisia’s career from the very point where the London exhibition ended, namely her long stay in the capital of the Spanish viceroyalty, interrupted only by a trip to London between 1638 and 1640 where her father Orazio lived.

The itinerary is developed in a single exhibition space dominated first by black and then by red, against which the masterpieces on display are silhouetted, creating through evocative and evocative lighting chiaroscuro effects that immerse the visitor in seventeenth-century and theatrical atmospheres. The development in a single exhibition space is made possible by the choice to present a fairly small number of works, about fifty in total, about twenty of which were created by the painter, while the others were by artists mostly active in Naples in the same period and closely related to her, such as Massimo Stanzione, Paolo Finoglio, Francesco Guarino, Andrea Vaccaro, Bernardo Cavallino and “Annella” Di Rosa, the leading Neapolitan artist of the first half of the seventeenth century. Works from important Neapolitan institutions, such as the Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, the Archivio di Stato and the Università degli Studi di Napoli L’Orientale, from the collections of Intesa Sanpaolo, but also from prestigious national museums, such as the Pinacoteca di Bologna, and international ones, such as the National Gallery in London, the Nasjonalmuseet in Oslo, the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm and the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

Arrangements for

Arrangements for Arrangements of the

Arrangements of the Arrangements of the

Arrangements of theThe exhibition kicks off from three “containers” in the center of the room and starts precisely from theSelf-Portrait acquired from the National Gallery in London, which is being exhibited in Italy for the first time, thus creating through the masterpiece a bridge between the great London exhibition in 2020 and the current Neapolitan exhibition running until March 20, 2023. InSelf-Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria, probably made shortly after her arrival in Florence (in 1616 she became a member of the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno and was one of the first women to enter it), Artemisia lends her features to the martyr saint; the painting dates from around the same time as theSelf-Portrait as a Lute Player from the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford and the Uffizi Galleries’ St. Catherine of Alexandria, as X-ray analysis of the Uffizi painting has revealed the presence of a turbaned figure beneath the image of St. Catherine that is almost identical to that of the National Gallery’sSelf-Portrait .

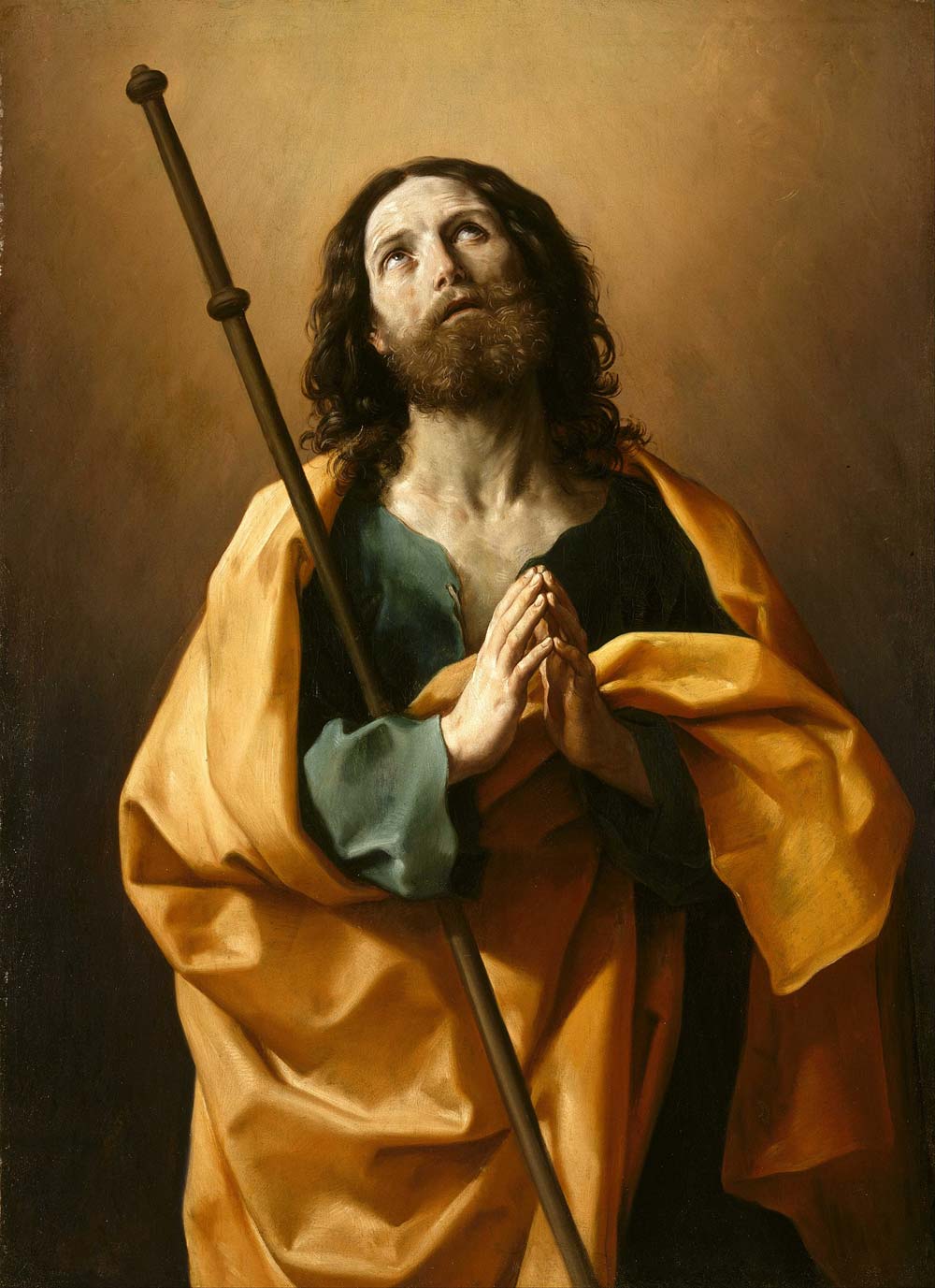

In another “container” was then partially reconstructed the cycle of canvases with Christ and the twelve apostles commissioned in Rome for the chapter house of the Carthusian monastery in Seville by the Duke of Alcalá Fernando Afán de Ribera III, viceroy of Naples from 1629. Now dispersed and only recently reassembled in its entirety from copies kept in Spain, the cycle was made between 1625 and 1626: in the center was the painting visible in the exhibition that depicts Jesus blessing the children made in 1626 by Artemisia, a painting that exhorted the monks to act with faith, propriety and humility, while around it figures of apostles were completed by artists such as Giovanni Baglione, Battistello Caracciolo and Guido Reni. Three rediscovered originals are exhibited here: the St. Andrew by Caracciolo, the St. James the Greater by Reni, and the St. James the Less by Baglione. A comparison is thus proposed between the painter and the artists who participated in the cycle, also linked to the city of Rome. Also placed in the same room is the only work in the exhibition by Orazio Gentileschi: a Christ and the Samaritan Woman at the Well, restored on the occasion of the exhibition in order to understand its undoubted artistic quality, which comes from the Spanish royal collections and had previously been attributed to Massimo Stanzione, but in which in fact are found, as Carmen Garcí writesa-Frías Checa in the catalog entry, “the solidity of the models, the chromatic contrasts of the light colors and the language of the hands typical of Gentileschi’s Roman production of the period between 1606 and 1612, when the Caravaggesque lesson was by then assimilated.” This constitutes, however, the only father-daughter confrontation in the exhibition.

It then continues with three works, including two paintings and an engraving, which are intended to show a certain iconography of Artemisia, a female figure with a proud gaze and rebellious hair, well integrated into the cultured society of the time, and an established painter who had managed to emancipate herself from the subordinate role to which women were subjugated. Here we see her here in theSelf-portrait as an allegory of painting at Palazzo Barberini while she is painting the face of a gentleman with a musketeer’s moustache, which Francesco Solinas has proposed to identify with Francesco Maria Maringhi, the Florentine lover of the painter, according to the correspondence he found in the archives of Casa Frescobaldi along with Michele Nicolaci and Yuri Primarosa. And in Clio muse of History, a painting from the Pisa Foundation in Palazzo Blu, signed and dated 1632, with which the painter intended not only to keep her memory alive among the Medici courtiers, but at the same time to claim her own role in History. Theengraving by the Frenchman Jérôme David , on the other hand, was executed after 1626 (the year of the founding of the Roman literary academy of the Desiosi, of which she was a member) from a lost self-portrait: although by a still inexperienced hand, it fixes Artemisia’s characteristic features as a genius of painting and confirms her claimed status as an artist and literary woman, reaffirmed by the Latin motto inscribed under the portrait (“miracle in painting, easier to envy than to imitate”), attributable, according to Pliny, to the Greek painter Zeusi. Finally, two documents are exhibited, the result ofextensive archival research, carried out on the occasion of the exhibition, for an update of studies on the painter, which have made it possible to acquire new data on her biography, including Artemisia’s arrival in Naples, in 1630, directly from Venice, her last years dominated by difficulties economic difficulties, the private affair relating to the concubinage of her daughter Prudenzia Palmira and the reparatory marriage that followed the birth of her grandson Biagio, but also of her artistic production, such as the role of viceregal and bourgeois patronage. The two documents on display concern a plea by Artemisia to stop a payment and the reparatory union between her daughter Prudenzia and Antonio De Napoli.

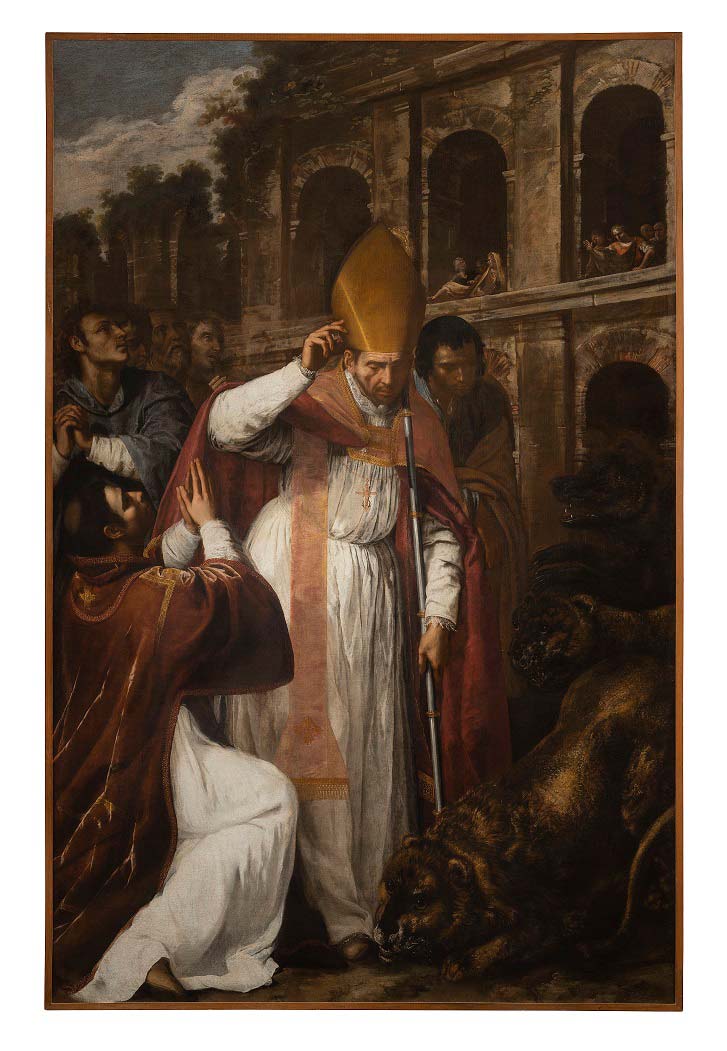

Having finished the tour in the three central “containers,” the exhibition continues with a section devoted to the major commissions she received in the first phase of her Neapolitan sojourn. In particular theAnnunciation from the Capodimonte Museum, fundamental for the reconstruction of the Neapolitan production because it is signed and dated on the cartouche present in the lower right-hand corner (1630); confirming the dating of the work is a correspondence between Artemisia and Cassiano dal Pozzo, an intellectual and collector (his collection is among the best known in Rome in the early 17th century) residing in Rome from whom the painter in the Neapolitan city hoped for protection: the painter tells Cassiano that she had to deliver some paintings forEmpress Eleonora Gonzaga by mid-September and had been away from Naples several times to paint a portrait of a countess before December 21, 1630. Maria Cristina Terzaghi writes that "at present we do not know how theAnnunciation fits into this sequence of works, but it is certain that it stands as her first surviving Neapolitan commission. Since the painter could have been in the city as early as March 1630, it cannot be ruled out that the canvas was made in the spring of that year." The scholar asserts that Artemisia would import into the Neapolitan artistic milieu an international flair, already visible in this painting in the puffy and sumptuous silken draperies of the Virgin and the angel, probably looking to Nicolas Régnier, who was active in Italy and particularly in Venice when the painter passed through. Also on display here are two monumental paintings that the artist made between about 1635 and 1637 for the choir of Pozzuoli cathedral, belonging to a cycle of depictions of the lives of Christ and Mary and the founders of the Church of Pozzuoli commissioned by the Augustinian bishop Martín de León y Cárdenas from the leading artists active in Naples at that time, such as Giovanni Lanfranco, Jusepe de Ribera and Massimo Stanzione. These are St. Gennaro and companions thrown into the amphitheater tame the beasts and St. Proculus and St. Nicea, the latter restored especially for the exhibition. A valuable unpublished coeval copy of the Birth of St. John the Baptist preserved at the Prado Museum also gives an account of another important commission to Artemisia: she painted the scene of the same name for the series of Stories of the Baptist destined for the Buen Retiro palace in Madrid for King Philip IV of Spain on the commission of the VI Count of Monterrey, viceroy of Naples.

Among the great themes addressed in Artemisia’s entire career is certainly that of certain female protagonists drawn from the classical and Judeo-Christian imagery who became, also in relation to the biography of the artist herself, true symbols of theaffirmation of women, their courage and strength: above all, Judith and Holofernes. The exhibition here features five paintings centered on “strong and intrepid women,” including two by Gentileschi depicting Judith and her handmaiden with the head of Holofernes, from the Capodimonte Museum, in which Terzaghi notes a change of register from the violence of the earlier versions and a predilection toward “the narrative of the pathos following thekilling of the Assyrian general, and the suspended atmosphere of the candlelight contributes in no small part to the effect,” and from the Nasjonalmuseet in Oslo; the latter, among the most significant new works presented in the exhibition, although hitherto known to scholars only through photographic reproductions, is signed and was acquired in 2022 by the Norwegian museum. The other three have Samson and Delilah as their common theme and were executed by three different artists: by Artemisia the one in the collection of the Gallerie d’Italia in Naples, by Hendrick De Somer, among the personalities emerging as one of the most interesting and original active in Naples during the first half of the seventeenth century, and by Diana “Annella” De Rosa, the leading Neapolitan artist of the first half of the seventeenth century, who according to an ancient but unreliable tradition was also a victim of gender violence. The latter is a work in which there is a variety of expression and richness in detail, particularly the still life with musical instruments in the lower left corner.

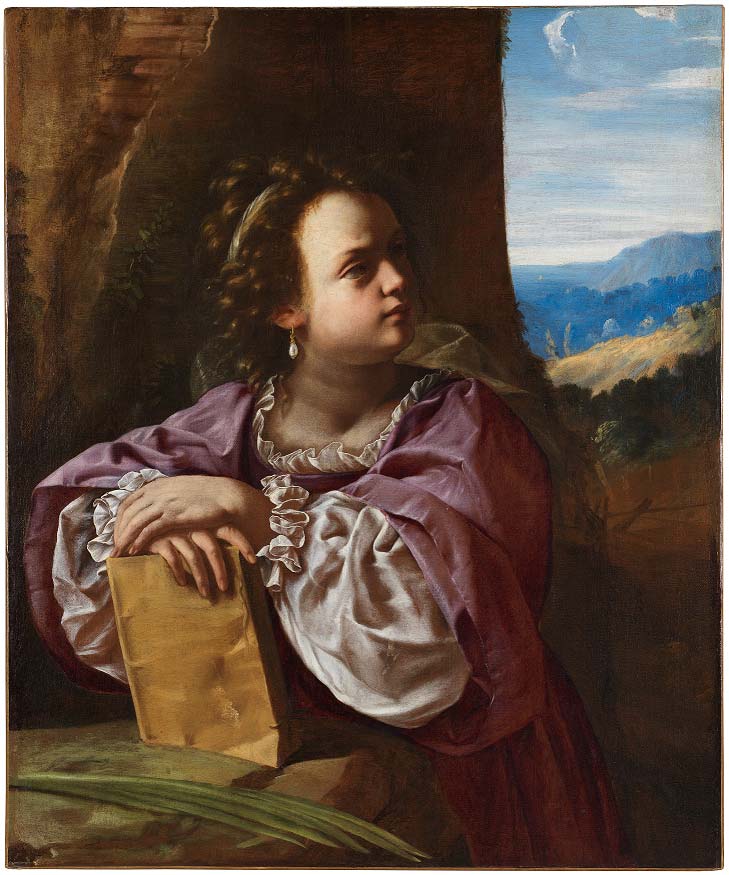

The exhibition continues with a selection of female figures depicting martyr saints, mostly half-length and recognizable by their attributes: for the most part they focus on the figure of St. Catherine of Alexandria. Among these is on display in the exhibition an absolute novelty for the Italian public, namely the Saint Catherine of Alexandria from the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm, which is immediately striking for its rendering of the fabrics and its mastery in the use of color. Carina Fryklund writes, "Here Artemisia reinterprets the subject from what she had already done in other paintings of the mid-1710s, offering a new and original image. The conventional attributes of the saint-the halo, the crown, the torture wheel-are absent, the ruins behind the figure probably allude to her name, as explained in the Legenda aurea, but the emphasis is on the large volume on which the woman rests her hands, an emblem of erudition associated with the saint when she is portrayed as the patroness of education and study." The painting is placed here in comparison with other paintings depicting the saint, such as the one by Paolo Finoglio in the collections of the Christian Museum in Esztergom, Hungary, or the one by Giovanni Ricca in the Palazzo Madama in Turin, which defines the coordinates of one of the main strands within which Artemisia fits in during her Neapolitan years, namely the depiction of half-figure saints. The refinement of the chromatic accords and the pearly whiteness of the skin bring to mind the lesson of Jusepe de Ribera, the dominant personality of painting in Naples in the first half of the 17th century, whose work on display is a half-figure Saint Lucia , also a characteristic trait of Massimo Stanzione.

After the heroines and saints, the next section is devoted to Eros and Thanatos, where theeroticism of nude or half-naked women from mythological tales or Old Testament episodes, immersed in architectural and landscape backgrounds, alternates with tales of violated women and the theme of death. On display here by Artemisia are the celebrated masterpiece in the Pinacoteca di Bologna depicting the theme of Susanna and the Old Men, signed and dated 1652 and currently considered the last certain work of the painter’s production, the Death of Cleopatra in a private collection on which scholars agree that thework to the painter’s early Neapolitan period thanks to comparisons with stylistically similar works, such as Susanna and the Old Men in a private collection in London and Bathsheba at the Bath of the Palatina Gallery in Florence, of which the catalog entry by Cristina Gnoni Mavarelli states that "the chronological placement in the early Neapolitan period (c. 1635) is the most plausible proposal in light of the peculiar characteristics of this phase of Artemisia’s activity, such as the marked predilection for the preciousness of the decorative elements (the shiny metal furnishings, the jewelry), the reference to Horace’s works of the 1630s (see Moses Saved from the Waters in the National Gallery in London), the calm setting of the female characters, lacking the energetic vigor of the figures of the Florentine phase." These works are compared with others by major artists of the time, such as Andrea Vaccaro, Agostino Beltrano, and Hendrick De Somer, often close to Artemisia’s taste, all three of whom are present with the theme of Lot and his daughters.

Little remains of the sacred production for private use and thus of small format that Artemisia produced during her Neapolitan years, and these are works that tie in with the critical debate about Artemisia and her active Neapolitan workshop, since traits of other artists as well as the painter’s own hand can be recognized in them. These include the Judgment of Paris from Vienna, in which the hand of Micco Spadaro has been recognized, the Sarasota pendant with the Triumph of David and Bethsheba at the Bath, to which both Spadaro and Onofrio Palumbo probably collaborated; by the latter, a documented collaborator of Artemisia, is exhibited is the Holy Family with St. Anne and St. Joachim from the church of Santa Maria Egiziaca in Pizzofalcone, which “offers a much better idea of how the painter’s style - from physiognomic types to the folds of drapery to color choices - intersects with Artemisia’s,” writes Giuseppe Porzio. "We are in fact, roughly speaking, at the chronological height of works such as the Susanna and the Old Men from the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna and the Madonna del Rosario from the Patrimonio Nacional, which have sometimes wanted to refer tout court to the Neapolitan artist, despite bearing the painter’s signatures in evidence." Also on display is precisely the Madonna del Rosario del Patrimonio Nacional, the only small-format specimen on copper explicitly signed by Artemisia. Such a medium is quite exceptional in the painter’s work: small-format paintings on copper dated back to a Flemish tradition and were widespread in 17th-century Italy, as evidenced by specimens made by Annibale Carracci, Guido Reni, Domenichino and Carlo Saraceni, among others.

The exhibition closes with four mythological fables: two paintings by Artemisia, namely the Corisca and the Satyr from a private collection and the famous Trionfo di Galatea made in collaboration with Bernardo Cavallino, evident in the forms and faces of the tritons, as well as in the velvety treatment of the surfaces, Massimo Stanzione ’sOrfeo dilaniato dalle baccanti and “Annella” Di Rosa ’s Ratto d’Europa from a private collection and exhibited to the public for the first time. Works displayed in the exhibition to reflect with a contemporary gaze on sex roles and gender violence, particularly in the attempted rape of the nymph Corisca, the abduction of Europa by Zeus and the killing of Orpheus by the Bacchae.

Artemisia Gentileschi in Naples follows an exhibition itinerary that privileges themes and comparisons over chronologies and has the merit of presenting a still little-known period of the famous painter, who spent her last years in Naples until her death. In fact, it is the first exhibition on the artist’s Neapolitan period, the last of her career and also the one characterized by less power both in the scenes and in the colors, which become more muted and blurred. It also has the merit of having conducted in-depth archival research and careful studies for the exhibition that have revealed new elements about his biography and his production related to the Viceroyal patronage. The catalog also includes appendices with a rich section of documents, most of them unpublished or little known, through which aspects of Artemisia’s Neapolitan biography are intended to be better elucidated.

The visitor also has the opportunity to admire for the first time in Italy such masterpieces as theSelf-portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria recently acquired from the National Gallery in London, and which as stated also has the role in the current exhibition of acting as a bridge and thus a continuation with the previous major exhibition held in London; the Triumph of Galatea from Washington, the Saint Catherine of Alexandria from Stockholm and the Judith and Holofernes from Oslo. And to see Artemisia’s works compared with those of other artists active in Naples at that time, following the same themes as the painter. Related to comparisons, the exhibition then has the merit of having partially reassembled, as previously explained, the cycle of the apostles for the Carthusian monastery in Seville. The theme of comparisons also opens a reflection on the critical debate on the workshop: we know in fact that in Naples Artemisia implanted a flourishing workshop availing herself of the collaboration of the best local artists, from Massimo Stanzione to Onofrio Palumbo to Bernardo Cavallino. Giuseppe Porzio writes in his essay, "Judging by the large number of works more or less directly traceable to the painter, there is no doubt that Artemisia’s southern activity must have constituted in her day a phenomenon of vast commercial dimensions, a sure result of marked entrepreneurial skills, an astute strategy of self-promotion, as well as aesthetic factors. However, the protean and in some ways still elusive physiognomy assumed by Artemisia’s production during her long Neapolitan sojourn poses, as is well known, complicated problems of chronological and especially attributive definition, and this because such a large corpus of paintings, of essentially private destination and circulation and always oscillating between ’quality and industry’, is certainly the result of a well-organized workshop in which, in addition to his daughter Prudenzia Palmira (whose artistic physiognomy we are not yet able to isolate), younger and more gifted personalities transited, including Bernardo Cavallino and especially Onofrio Palumbo [....] For Gentileschi herself, her name was to count as a sort of trademark, guaranteeing more the ideational responsibility than the executive coherence of a product. Therefore, if already distinguishing Artemisia’s hand from that of her assistants is an extremely difficult operation, separating them is probably an illegitimate act. For this reason, therefore, in the exhibition it was decided to adopt the label “Artemisia” even for works where the participation of helpers is evident."

Finally, the exhibition has the merit of having introduced the painter Diana “Annella” De Rosa, displaying two of her works within the exhibition; in the exhibition itinerary, however, the visitor is not given any data to know the latter’s story, which is instead told in the catalog, without, however, better clarifying the issue of gender violence that is mentioned in the first exhibition panel of the exhibition (“according to an ancient tradition, which has, however, turned out to be unreliable, a victim of gender violence as Artemisia”). An exhibition and catalog that prove to be for all that fundamental tools on Artemisia’s Neapolitan period and from which to build further studies.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.