Art in the Ludovisi papacy, among the shortest of the seventeenth century. What the exhibition at the Scuderie del Quirinale looks like.

The most monumental altarpiece by Giovan Francesco Barbieri known as Guercino was commissioned to the Cento painter in 1621 by Pope Gregory XV, born Alessandro Ludovisi, for the head altar of the north aisle of St. Peter’s Basilica, where in 1606 the remains of St. Petronilla, a saint much venerated by the Catholic Church, martyred in Rome precisely for embracing the Christian faith and considered according to tradition to be the natural or spiritual daughter of the apostle Peter, had been placed. The masterpiece now housed in the Capitoline Museums (since 1818, since it was brought back to Italy by Antonio Canova because it had been requisitioned by Napoleon’s troops, and already in 1730 transferred to the Quirinal Palace and replaced by a mosaic reproduction by Pietro Paolo Cristofari) depicts on two levels, because of its vertical arrangement, precisely the Burial and Glory of Saint Petronilla: we see her in the lower foreground with her head adorned with a crown of fresh flowers while two men are lowering her body into the tomb (the one dressed in blue has moreover been identified by two critics as Michelangelo Buonarroti), plus one whose hands are visible only, among some bystanders pointing at her and others observing the scene, above which we see instead the admission of the saint into heaven, with Christ rising from his throne of clouds surrounded by angels. It is a masterpiece distinguished by its dynamism, color contrasts, and above all a profound humanity and naturalness.

Kicking off precisely from this monumental work, with a life-size facsimile of it, is the major exhibition that runs until January 26, 2025 in the exhibition spaces of the Scuderie del Quirinale in Rome, entitled Guercino. The Ludovisi Era in Rome, curated by Raffaella Morselli and Caterina Volpi. The exhibition, as one might think from the title, is not a monographic exhibition dedicated to Guercino’s art in the years of the Ludovisi papacy, but an exhibition on theLudovisi era where Guercino is among its main protagonists. Through the exhibition itinerary, in fact, the public has the opportunity to retrace the brief but influential pontificate of Gregory XV Ludovisi, which lasted just two years (it was among the shortest of the seventeenth century, from 1621 to 1623) and was characterized by important initiatives on both the political and cultural levels. On the one hand, the pope strengthened the universal role of the Catholic Church through the establishment of the Congregation of Propaganda Fide and support for the global mission of the Society of Jesus; on the other hand, with the support of his nephew Cardinal Ludovico, an enlightened patron of the arts, he initiated a period of extraordinary artistic and cultural flourishing, with the promotion of great artists and the creation of one of the most celebrated art collections of the time. In order to give an understanding of the artistic richness of this period, Guercino’s works are accompanied, and sometimes compared, in the sections of which the exhibition is composed, with the works of the best artists who made Rome the propelling center of artistic activity in those years: Guido Reni in particular, but also Domenichino, Giovanni Lanfranco, Annibale and Ludovico Carracci, Pietro da Cortona, Nicolas Poussin, and Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

The protagonists of the first section, however, are Guercino and Pope Gregory XV Ludovisi: the former depicted in the Half-BustSelf-Portrait from the Schoeppler Collection in London, among the very few self-portraits of his production, and the latter represented by the bronze bust made by Gian Lorenzo Bernini that was in the hall of honor of the Casino Ludovisi, under the fresco of Fame executed by Guercino. Here, then, begins, along with the aforementioned Altarpiece of St. Petronilla and a view of the interior of St. Peter’s Basilica created by Pietro Francesco Garola in which the altarpiece is included, the story of the Ludovisi pontificate intertwined with the painting of the young artist who lived one of the most significant moments of his career in Rome.

Although Guercino is often considered self-taught, his training was profoundly influenced by the Carraccis, particularly the so-called Carraccina, on display in the exhibition, painted by Ludovico Carracci in 1591 for the church attached to the Capuchin convent in Cento, Guercino’s hometown. The artist thus had the opportunity to study the expressive naturalism typical of Emilian painting on this Holy Family with St. Francis and Donors. And in 1617 he had the opportunity to see in Bologna the great altarpieces by Annibale and Ludovico Carracci from which he assimilated the ability to create theatrical and engaging sacred compositions, as seen, for example, in the painting, also on display here, one of the first signed by the artist, depicting St. Bernardine of Siena and St. Francis of Assisi praying to the Madonna of Loreto executed for the church of San Pietro in Cento.

These paintings are followed in the exhibition itinerary by four canvases with a strong theatrical impact made in 1618 that constitute the first tests commissioned to the Cento painter by Alessandro and Ludovico Ludovisi in the period before the Roman period. In fact, the bond between Alessandro Ludovisi and Giovan Francesco Barbieri initially developed in Bologna, where the future pope held the position of cardinal legate. Although Ludovisi had contacts with important artists of the time, such as Ludovico Carracci and Guido Reni, his main interest focused on the young Guercino. It was thanks to canon Antonio Mirandola that Guercino received his first public commissions, as the latter, in 1612, was so impressed by the painter’s creative ability that he became his agent and, in 1615, had him exhibit in Bologna a Saint Matthias that attracted the attention of Ludovico Ludovisi, nephew of the future pope. The artist was then invited to lunch at Palazzo Ludovisi, where he met Lavinia Albergati, wife of Orazio Ludovisi, Alessandro’s brother. This meeting marked the beginning of the painter’s relationship with the Ludovisi family, which would later be consolidated in Rome. Two years later, in 1617, Guercino moved to Bologna, where his painting was noticed by Ludovico Carracci, who in two letters dated the same year praised the modus pingendi of the young Cento painter, describing him as a “monster of nature” for his extraordinary painting skills.

The beginning of a commissioning relationship that would have a major impact on Guercino’s career was thus marked by the four works mentioned, depicting The Return of the Prodigal Son, Lot and the Daughters, Susanna and the Old Men, and Saint Peter Resurrects Tabita, brought together here on this occasion thanks to loans from Madrid, the Uffizi Galleries, and the Royal Museums of Turin. However, attention for the painter from Cento had spread to Rome even before his arrival in the capital thanks to works such as Erminia finds wounded Tancredi, also in the exhibition, commissioned by Marcello Provenzale, a mosaicist from Cento, and sent as a gift in 1621 to Stefano Pignatelli in Rome for his appointment as cardinal.

The eye is captured at this point by the large canvas, on public display for the first time, of Domenichino ’s Original Sin executed in collaboration with Giovan Battista Viola and Elia Maurizio. The painting, which immortalizes the instant when Eve discovers she is naked and crouches down allowing Adam to assume a Michelangelo-esque Adam pose, is a triumph of lush exotic nature and the rich variety of animal species. A work-manifesto of the art promoted by Ludovico Ludovisi and the Accademia dei Lincei that combines references to antiquity, modern painting, and the naturalistic and zoological repertoire, it introduces the exhibition spaces dedicated to the Villa Ludovisi, the sumptuous mansion that was responsible for publicly declaring the prestigious role of the new pontiff’s family. Built on the remains of the ancient Orti di Sallustio starting in 1621 with the acquisition of the vineyard and Casino formerly belonged to Cardinal Del Monte, the Villa included the palace of representation, where the Ludovisi collection composed of ancient and modern statues and paintings by the great masters of the Renaissance and modern painters was kept, and the Casino, where the precious and smaller works were gathered and where one of Guercino’s most famous masterpieces can still be admired in the vault of the central hall on the ground floor: the fresco of Aurora on the chariot within an illusionistic quadrature by Agostino Tassi, with the figures of Night and Day. The masterpiece, a masterful example of Guercino’s ability to combine mythological and natural elements in a composition that celebrates time and universal harmony, is recreated here through projections on the ceiling and walls, followed in the next room by Guercino’s studies and drawings for the fresco and drawings by other artists to testify to the fortune this subject had. Also featured are theAres Ludovisi, found in the Campitelli district, in the area of the Santacroce Palace, purchased by Ludovico Ludovisi in 1622 and restored in the same year by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, who intervened obsequiously for some anatomical details and with extreme freedom at the hilt of the sword and in the Cupid, and the Chariot of Venus made in tempera by Pietro da Cortona.

One of the most interesting aspects of the exhibition is the comparison between Guercino and Guido Reni, two of the greatest painters of the Italian seventeenth century who played a privileged role in the Ludovisi era. This comparison concludes the exhibition on the second floor with the presentation of two extraordinary altarpieces: the Crucifixion with the Virgin and Saints John the Evangelist, Mary Magdalene and Prospero patron saint of Reggio made by Guercino between 1624 and 1625 for the Basilica of the Ghiara in Reggio Emilia, second in size only to the Altarpiece of Saint Petronilla, and the Trinity of the Pilgrims made by Guido Reni between 1625 and 1626, commissioned by Cardinal Ludovisi for the church of the Holy Trinity of the Pilgrims in Rome on the occasion of the Jubilee proclaimed by Pope Urban VIII on April 29, 1624. Guercino’s Crucifixion, with its dramatic chiaroscuro and emotional tension, is a perfect example of the pathos and realism that characterize his work. In contrast, Guido Reni’s Trinity of the Pilgrims is a masterpiece of luminous classicism and symmetry. A comparison between the two artists offers a unique insight into the different artistic sensibilities of the time, as can also be seen in the different depictions of St. Philip Neri by one and the other painter and the Heads of Christ Crowned with Thorns. Also worth the exhibition alone is the Moses recently entered in Guercino’s catalog: a close-up portrait of the prophet caught in the midst of an ecstatic vision and illuminated on the head by two rays of light.

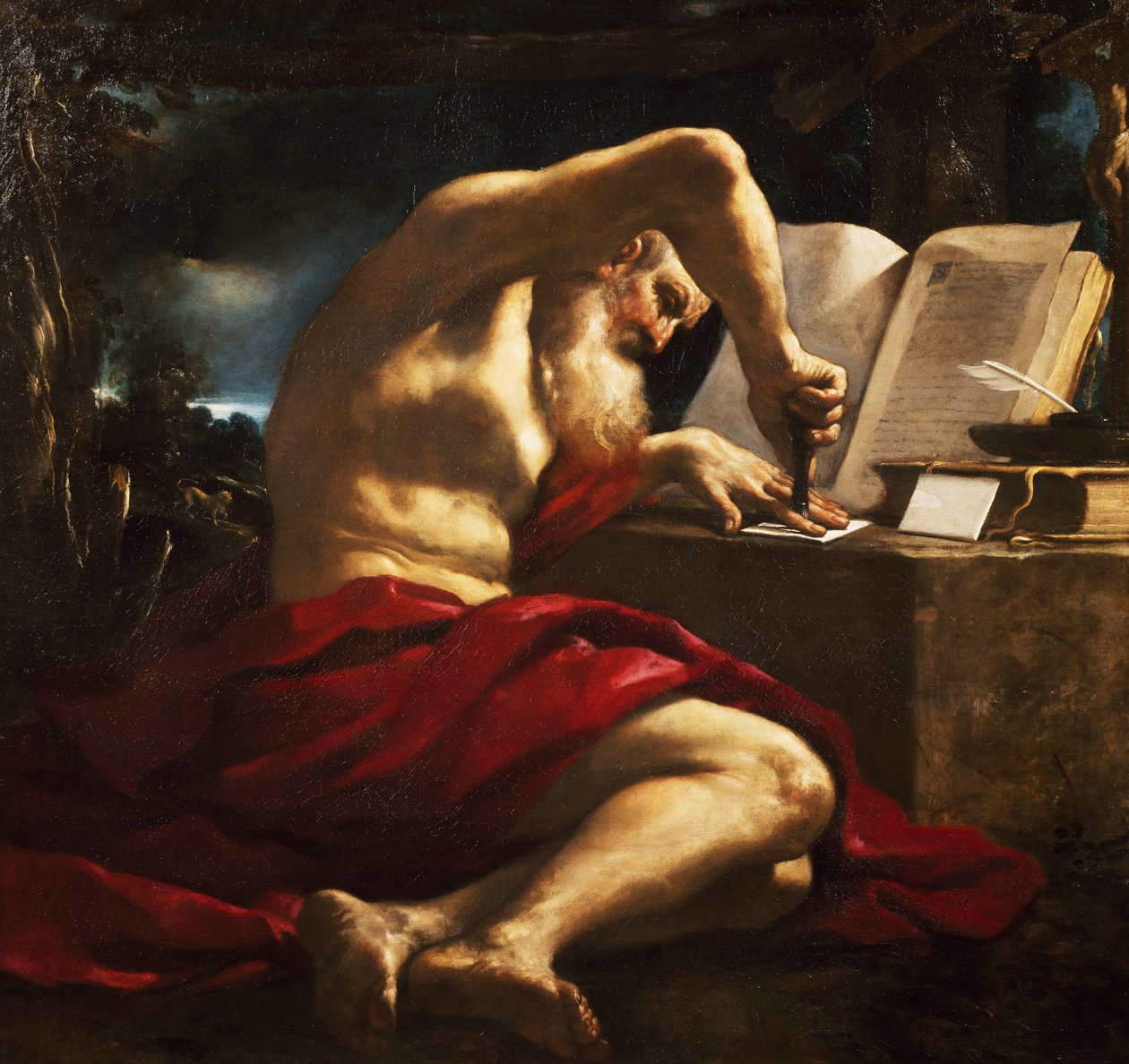

The second floor opens with paintings that testify to how Guercino’s fame spread rapidly in the aristocratic circles of the capital: the Roman period represented a real turning point for his career, and his painting won the favor of the Roman elite for its expressive force, perspective innovation and realistic details. We then see the Saint Jerome preserved in the Palazzo Barberini, where the painter depicts the saint in a moment of profound humanity, intent on sealing a letter. The twisting of the body, the realistic details and the domestic intimacy of the scene are distinctive features of the painter’s style, which combined naturalism and emotional involvement. The painting is attested in the post mortem inventory of the estate of Marquis Valerio Santacroce. We see The Capture of Christ, from Cambridge, painted shortly before the artist moved to Rome, which is characterized by its great theatrical impact and dramatic realism, evident in the gestures and expressions of the characters. It was executed with TheIncredulity of St. Thomas from the National Gallery in London for Bartolomeo Fabri, owner of the premises where Guercino had installed theAccademia del Nudo in Cento since 1618. Also, St. Matthew and the Angel, documented in the rich collection of Cardinal Carlo Emanuele Pio of Savoy; and the Return of the Prodigal Son, attested to be owned by the Lancellotti family, among the most important Roman families.

Guercino also obtained a privileged place among the protégés of Scipione Borghese, who after admiring some of his easel works decided to entrust him with one of the most important public commissions of the time: the monumental San Crisogono in gloria (shown in facsimile), intended for the ceiling of the church of San Crisogono in Trastevere. The work, completed in 1622, is an extraordinary example of Baroque ceiling painting, with well-defined forms and bold perspective (note in particular the saint’s knees placed foreshortened to the viewer). Removed from the church in the 19th century and replaced with a copy, the original painting is now in Lancaster House in London.

As mentioned above and as we have already noted throughout the exhibition itinerary, there are other artists besides Guercino in the exhibition: if so far we have encountered in particular Domenichino, Guido Reni, and Gian Lorenzo Bernini, now in this next room we find on display painters who were influenced by Venetian painting. During the pontificate of Gregory XV, Ludovico Ludovisi’s acquisition of Titian’s famous Bacchanals, namely The Offering to Venus and The Bacchanal of the Andrii (featured here in copies by Padovanino and Scarsellino), originally made for Alfonso d’Este and now housed in the Prado Museum, marked an extraordinary event for art in Rome. These masterpieces, from the collection of Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini and later acquired by Ludovico Ludovisi, profoundly inspired the birth of the “neo-Venetian” artistic current, which influenced European painting for a long time. The themes of Mars, Venus and Cupid, recurring in the Ludovisi collection and represented in the works of Titian, generated a strong inspiration that is reflected in the paintings with cupids and cherubs by Poussin(The Bacchanal of Putti), Domenichino(Allegory of Agriculture, Astronomy and Architecture), Guido Reni(Struggle of Cupids and Bacchae) and Francesco Albani(Dance of Cupids), as well as in the sculptures of Bernini, Algardi and Duquesnoy. A significant example of the influence exerted by this collection is Guercino’s painting Venus, Mars and Love , made in 1633 for Francesco I d’Este, which we can admire in the center of this room (note how Cupid’s arrow and Venus’ index finger always point toward the viewer). This work is steeped in references to classical sculpture and Venetian painting , showing how much the Roman sojourn had permeated the artist’s style. Other works of the period, such as Pietro da Cortona’s The Triumph of Bacchus and Antoon van Dyck ’s Amarilli and Myrtle shown here, also show a connection to the Bacchanal of the Andrii and a particular influence of Guercino’sAurora.

Also featured here is one of Guercino’s masterpieces, Et in Arcadia Ego, first mentioned in his own hand in Antonio Barberini’s 1644 inventory and made by the painter after his return from Venice. And it is precisely to Arcadia and landscape painting that the penultimate section is dedicated. Ludovico Ludovisi, initially interested in landscapes of the Venetian and Ferrara schools, such as those of Jacopo Bassano, Palma il Vecchio and Dosso Dossi, favored an evolution toward an idealized representation of nature inspired byclassical Arcadia. This approach is evident in the commissions for the frieze of the Stanza dei Paesi in the Casino Pinciano, where Guercino, Domenichino, Giovan Battista Viola and Paul Bril contributed scenes celebrating an ordered and calm nature influenced by the Carracci school. In the exhibition, the new typology of the ideal landscape is represented by Domenichino’s Landscape with Hercules and Cacus (1621-1622) made for Ludovico Ludovisi; a monumental composition that combines an ideal view and a natural representation, with the introduction of mythological subjects. It was a vision of nature that continued to inspire later artists such as Pietro Paolo Bonzi, Pietro da Cortona and Agostino Tassi, who, as can be seen in his works on display, is influenced both by the Ludovisi marbles and by the painting of Guercino himself. Also on view are a number of landscapes by the latter, including the Paesaggio al chiaro di luna con carrozza (Moonlight Landscape with Carriage ) from Stockholm with its pendant Paesaggio con cavaliere e viandanti nei pressi di un fiume (Landscape with Horseman and Wayfarers near a River ) from a private collection, reunited after more than fifty years for this exhibition, made between 1616 and 1617 and both of which are influenced by Ludovico Carracci’s crepuscular atmospheres. Or the Paesaggio con Tobiolo e l’angelo, the painter’s only landscape, along with Et in Arcadia Ego, to be found in seventeenth-century collections and like the latter to boast a Barberini provenance.

The exhibition once again concludes with comparisons, parallel to the conclusion of the second floor of the exhibition: a triptych of portraits depicting Pope Gregory XV and his nephew Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi to further emphasize the two protagonists of the Ludovisi era. In the center is the Portrait of Pope Gregory XV and his new cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi made by Domenichino and from Béziers; on the right is the Portrait of Pope Gregory XV made by Guercino and from the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles; and on the left is the Portrait of Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi made by Ottavio Leoni and from the Szépművészeti Múzeum in Budapest. The difference in approach in the portrayal of the pontiff by Domenichino and Guercino is well noted: the former is official and refined, in line with the great portrait tradition of Raphael and Titian, while the latter is distinguished by its intimate and direct character, offering a private image of the pontiff intended for immediate involvement with the viewer. Domenichino depicts the pontiff seated three-quarter-length on a chamber chair covered in gold brocade with his nephew standing next to him, probably holding the letter of cardinal’s appointment in his right hand; Guercino, on the other hand, depicts Pope Gregory XV seated alone while looking at the viewer and with no objects that tend to enhance his role and pomp, in contrast to Domenichino’s portrait where elements allude to a greater refinement of detail, such as the finely chiseled bell, the embroidered cloth in the cardinal’s left hand, and the red slipper that can be seen under the pope’s white robe. Ottavio Leoni’s executed portrait of the cardinal also features details that allude to wealth and prestige, such as the inlaid chair upholstered in red velvet, the embroidered robe, and the gold ring with faceted diamond in the right ring finger.

This brings to a close an exhibition that has brought together paintings after many years, that has brought hitherto never exhibited works, and that has included in its itinerary not a few comparisons among the major artists of the seventeenth century, in addition to the extraordinary Moses that recently entered Guercino’s catalog. All in a well-constructed exhibition itinerary that is well explained by the section panels and the brief but clear descriptions accompanying the most significant works. Also useful is the catalog that includes fact sheets of all the works and essays devoted to Guercino in the Rome of the Ludovisi. An exhibition that rightly deserved to be among the most appreciated and visited of 2024.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.