From the Medici to the Rothschilds. Patrons, Collectors, Philanthropists is the new exhibition open at the Gallerie d’Italia in Milan from Nov. 18 until March 26, 2023, curated by Fernando Mazzocca and Sebastian Schütze, and produced in partnership with the Bargello Museums and the Alte Nationalgalerie - Staatliche Museen in Berlin. The exhibition, in the ideas of the organizers, aims to investigate the relationship between money and art throughout history: a complex, often obscure and controversial relationship, sometimes capable of generating unexpected synergies and restoring value to the community. “Money can also be an ethical force,” argues Giovanni Bazoli, chairman emeritus of Intesa San Paolo. Indeed, many artistic masterpieces would never have seen the light of day without support from financiers and bankers.

The Milan exhibition features more than 120 works from different eras on loan from major international museums such as the National Gallery in London, the Louvre in Paris, the Albertina in Vienna, museums in Berlin, and the Morgan Library & Museum in New York, and outlines an itinerary built around some unique figures of banker patrons from the Renaissance to the 1970s. These figures, presented in the eleven sections of the exhibition, were important patrons, far-sighted collectors and sometimes benevolent philanthropists, who carved out within the history of art an alternative path to that traced by ecclesiastical patronage, but no less interesting.

The Milan exhibition aims to trace the evolution over the centuries of patronage, beginning with the banking family that during the Renaissance had the most complete and fruitful dialogue with art, so much so that it became the very emblem of one of the most successful seasons between art and society, the Medici. The Florentine family had linked its economic fortunes and consequent social rise to the flourishing banking business promoted particularly between Florence and Lucca, as well as with branches abroad, including one in Bruges. The Medici managed to play an important political role on the Italian and European scene, thanks to figures who later became legendary such as Cosimo the Elder and Lorenzo the Magnificent, who transformed Florence into the capital of the arts within a few generations.

In this first section, moreover the richest and most interesting, some effigies of the protagonists of this era are exhibited, eternalized by the most celebrated artists of their time. The initiator of these fortunes, Cosimo the Elder, is shown to us through a silver medal, evidence of the renewed interest in ancient numismatics that characterized the Renaissance. Bronzino and Pietro Torrigiano, on the other hand, pass on Lorenzo’s likeness in painting and polychrome terracotta, respectively. Instead, from the National Archaeological Museum in Naples come four splendid cameos from the much-admired collection of ancient gems that was the pride of the Medici. The section on the Florentine family concludes with a small but explanatory selection of masterpieces, evidence of their active role as patrons and supporters of artists. On display is Andrea del Verrocchio ’s Putto con Delfino, a dynamic sculpture originally made as a decoration for a fountain in the Villa di Careggi. Next to it is Antonio del Pollaiolo’s bronze with Hercules and Antheus, in which the struggle generated by virtuosic twisting and turning alludes to the tension between human vices and virtues. Finally, on display is the extraordinary Michelangelo bas-relief, a tribute to Donatello’s stiacciato, of the Madonna della Scala from Casa Buonarroti.

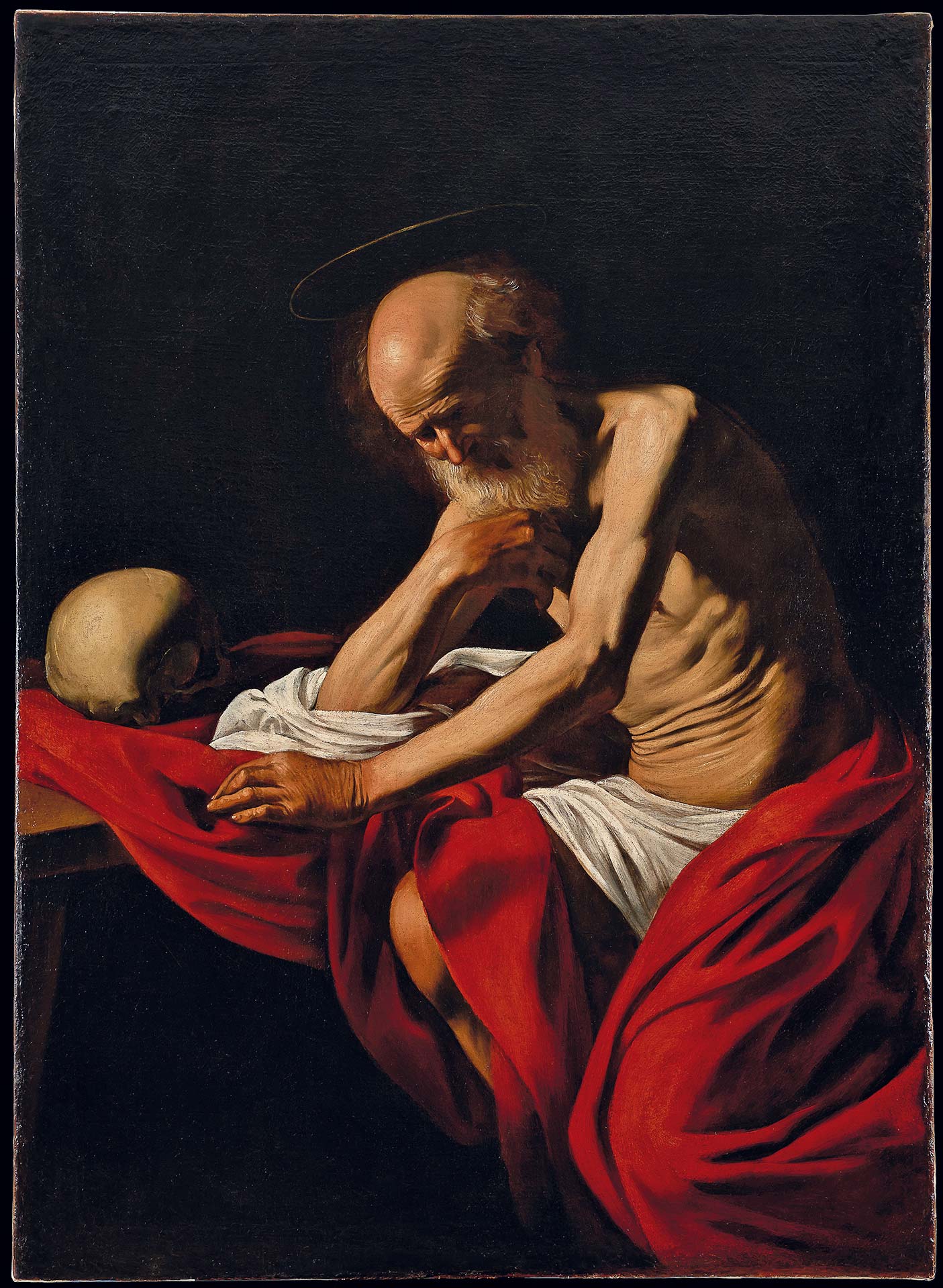

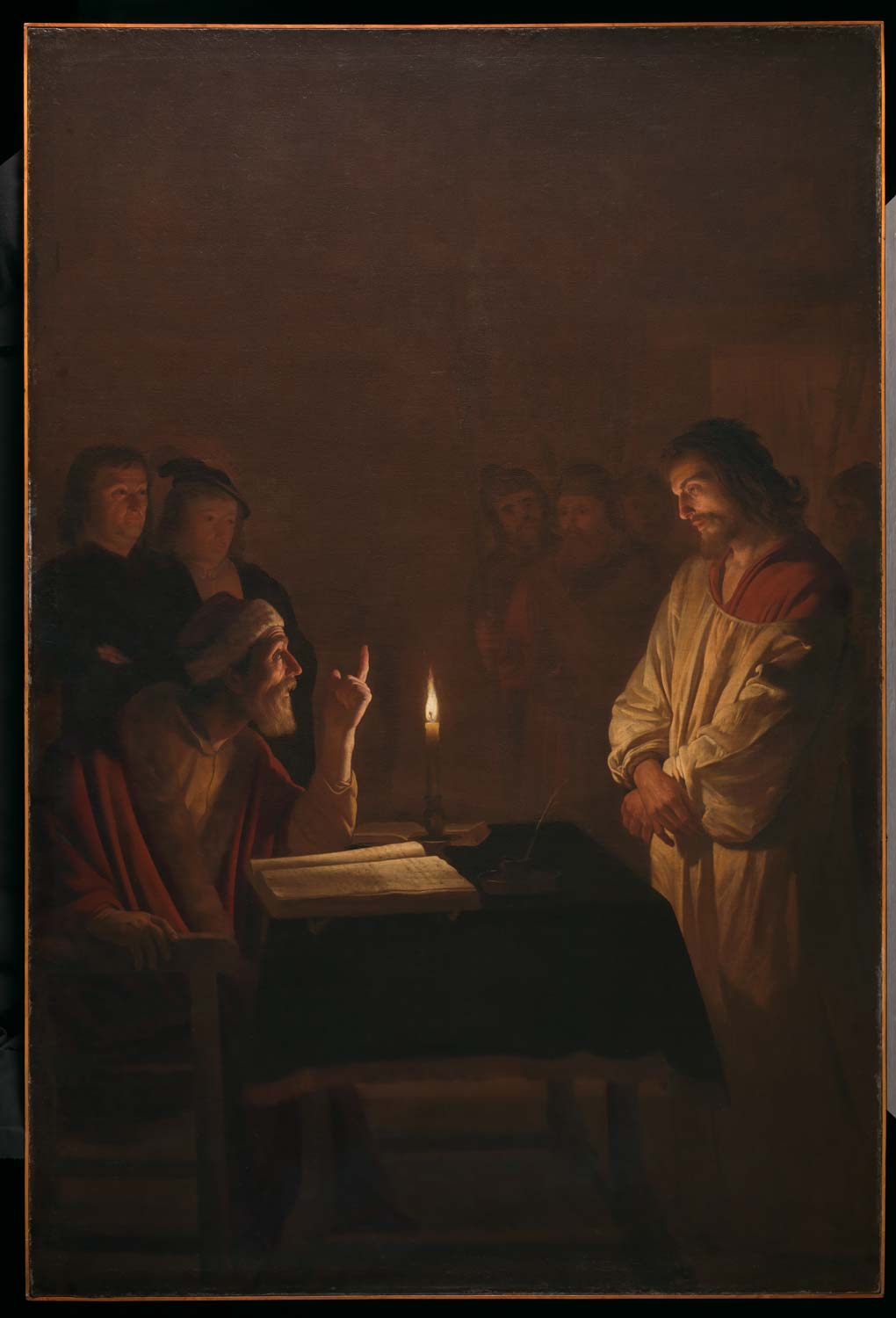

Instead, the affairs of Vincenzo Giustiniani, a banker of Genoese origin who had important financial interests with the Papal States, are Roman. He increased the collection of antiquities already started by his father, acquiring absolute masterpieces such as the Giustiniani Athena. This extraordinary collection was dismembered in the following centuries, but it is known to us thanks to some catalogs of which the celebrated Galleria Giustiniana, accompanied by descriptions and engravings, executed by important artists of the time, and exhibited here as a loan from the Apostolic Library. But Giustiniani also knew how to support the artists of his time: as evidence of this interest we find in the exhibition Caravaggio’s St. Jerome, for which he was among the main patrons, Gherardo delle Notti’s Christ before Caiaphas, a work by Valentin de Boulogne and a fine crucifix by Annibale Carracci.

Less well known to us Italians is probably the figure of Everhard Jabach, heir to a family of Dutch merchants and bankers. From a young age, following the family business, he entertained numerous trips between Flanders and London, to the court of Charles I, and it was from the court painter Antoon van Dyck that he had several portraits made, an example of which we find in the exhibition. In Paris, “the opulent banker,” as Francis Haskell called him, procured works of art for the collections of King Louis XIV. His gigantic private collection included paintings, sculpture, and above all, a substantial nucleus of drawings and prints by great artists, from Raphael to the Carraccis, Rubens, Dürer, Le Brun, and Poussin. Jabach gave part of this immense collection, over five thousand pieces, to the French ruler. These works became the backbone of the Louvre museum and its drawing cabinet, which has granted some loans to the Milan exhibition.

The collecting affairs of the Austrian banker and merchant family Von Fries is also recounted in Milan. In particular Moritz, whose fine painting by Swiss Angelica Kauffmann we can see, was credited with playing a leading cultural role in imperial Vienna around 1800. He was an honorary member of the Academy of Fine Arts and a patron of contemporary artists such as painters Heinrich Friedrich Füger and Josef Abel but also of musicians such as Joseph Haydn and Ludwig van Beethoven. But with the Napoleonic wars his financial fortunes ended and his formidable collection auctioned off was dismembered and a substantial part of his drawings and prints purchased by the Albertina Museum in Vienna.

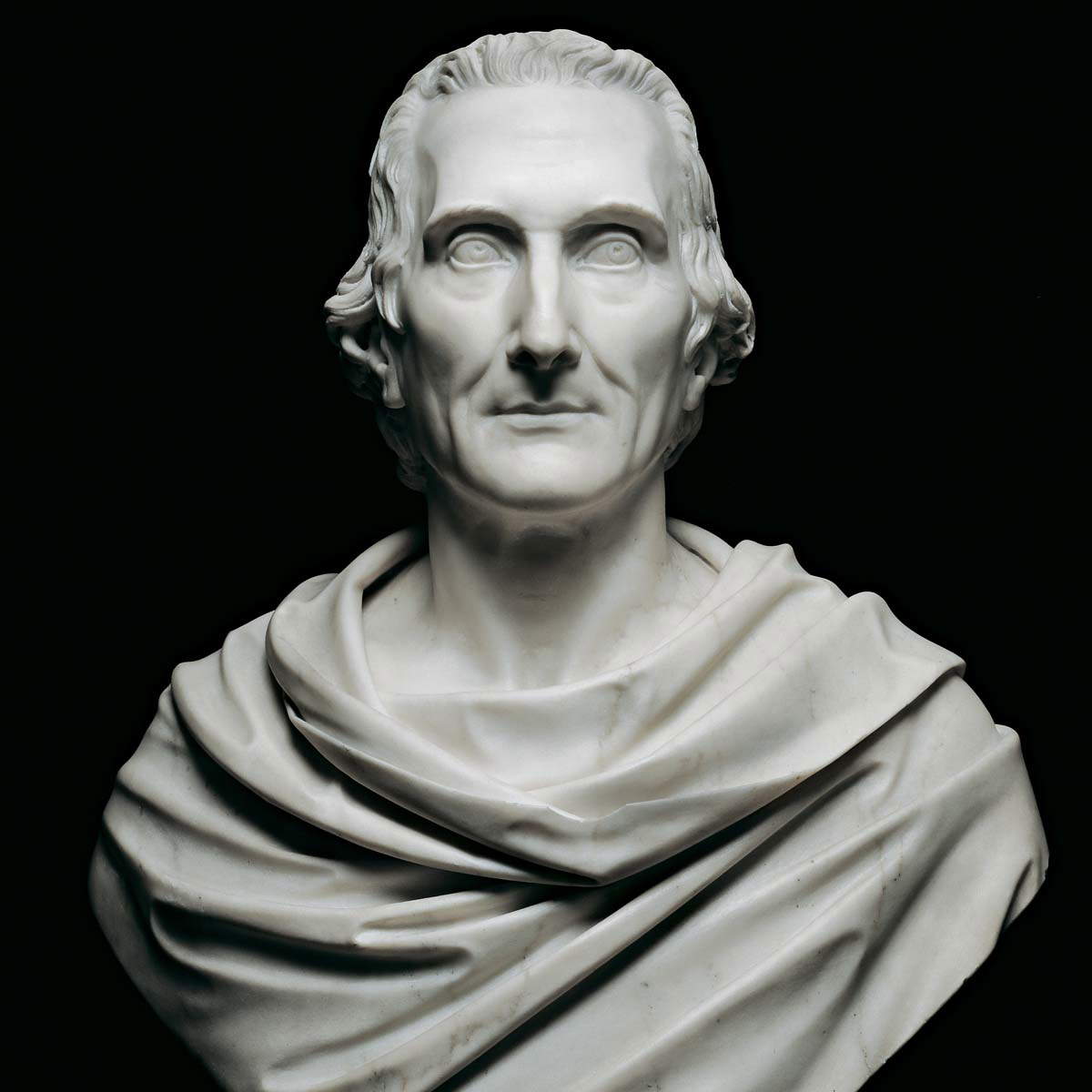

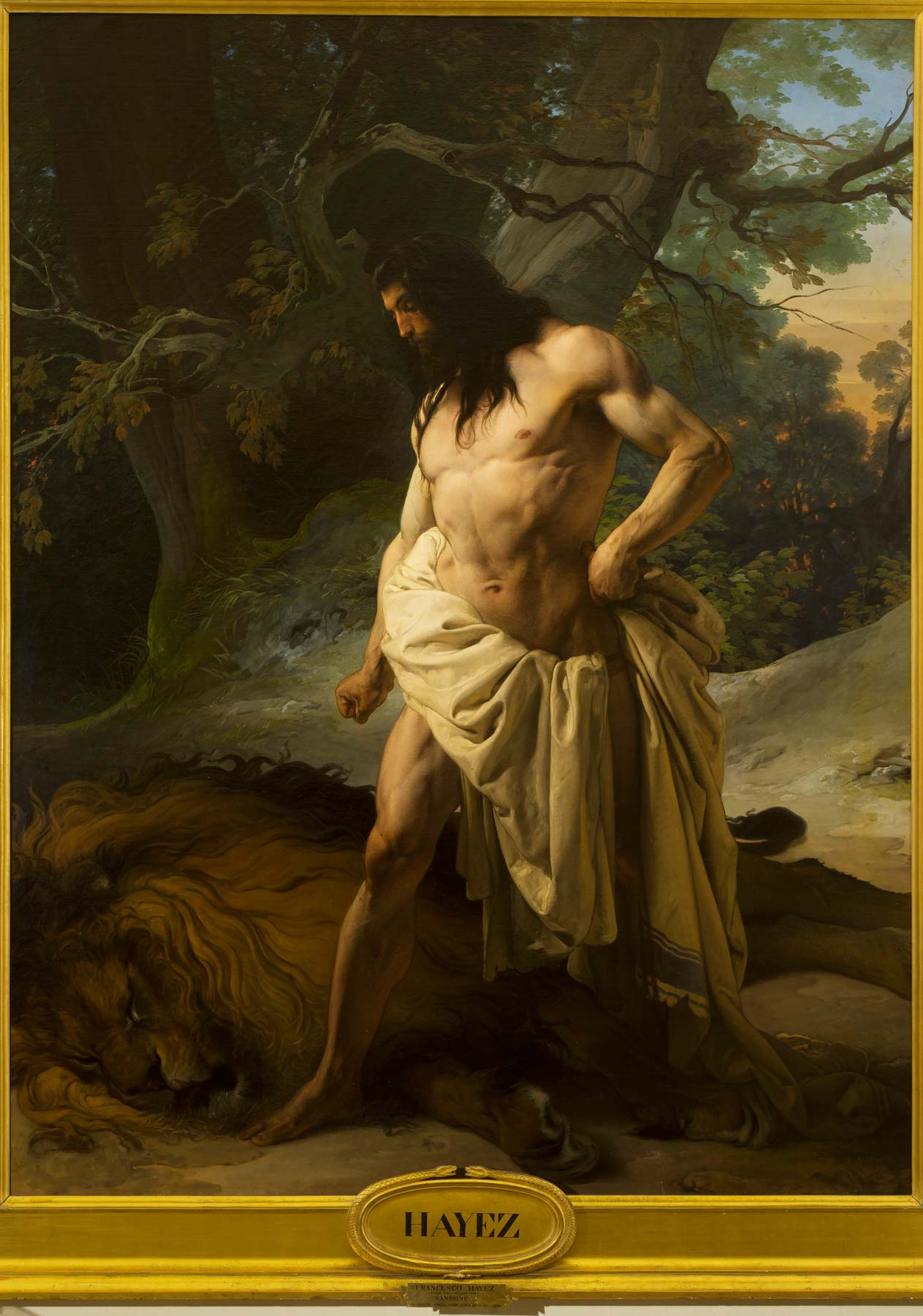

The same years also saw the experience of Giovanni Raimondo Torlonia who, on the contrary, derived economic benefits for his bank from the French occupations, so much so that he obtained the dignity of nobility, accompanied by a great commitment on the arts front. He restored the Basilica of the Holy Apostles in Rome, and obtained, following an extraordinary outlay and beating off competition from European sovereigns, the marble of Antonio Canova’s colossal group of Hercules and Lica, some engravings and bronze replicas of which are exhibited in Milan. The work was later set up together with numerous antique sculptures in the sumptuous palace the family owned in Piazza Venezia, later demolished in 1901, where the decorative apparatus was entrusted to painters Gaspare Landi and Pelagio Palagi, with the collaboration of a young Francesco Hayez. In addition to evidence of these multiple interests, the splendid portrait of the banker sculpted by the Dane Bertel Thorvaldsen also appears in the exhibition.

Also behind the origins of the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin is the figure of a banker, that of Joachim Heinrich Wilhelm Wagner, who, leaving his boundless collection to the King of Prussia Wilhelm I, imposed by testamentary bond that a national gallery be founded.

In Lombardy, on the other hand, the collecting experiences of Heinrich Mylius and Ambrogio Uboldo, two bankers with very different histories who contributed to the rise of Milan as the capital of art and to the support of Italy’s national painter, Francesco Hayez, and numerous others, take place. Also on display is Carlo Bossoli ’s fine painting from the Museum of the Risorgimento in Milan, showing Uboldo’s collection looted by rioters during the Five Days of Milan in 1848, in particular antique weapons were robbed to confront the Austrians.

Another section is devoted to Nathaniel Meyer von Rothschild, a member of the prominent Austrian banking family that had offices in London, Paris, Naples and Vienna. Nathaniel was the patron of a sumptuous palace completed in 1879 by French architect Jean Girette, and whose interior design he also oversaw, so much so that it became a total work of art. Arranged here was his collection composed of masterpieces of Italian art, such as the Portrait of Altobello Averoldi from Francia, on loan from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, and from the great masters of the French 18th century: a sample of which is on display in the Toilette by François Boucher. Here in a meticulously described interior where every object is charged with its own charm a frivolous and typically voyeuristic scene in keeping with the taste of the time unfolds.

From overseas is the story instead of John Pierpont Morgan, who in the United States founded the first investment bank in the modern sense. Morgan was also a major collector of works ranging from ancient art to Renaissance art to contemporary art. Some of his works flowed into the Pierpont Morgan Library, while others went to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, of which he was also president from 1904 to 1913. The American tycoon purchased these works firmly convinced in the cultural elevation of his homeland, and the sculpture Bust of America by Hiram Powers on display shares the same spirit.

Finally, the exhibition concludes with an extraordinary figure with particularly symbolic values for the exhibition, Raffaele Mattioli, who was appointed in 1933 general manager of the Banca Commerciale Italiana, which had its headquarters in the building in Piazza della Scala, where the exhibition is now held. Also called the “humanist banker” for his interest in art and culture, he was a friend of literati such as Benedetto Croce and critics such as Roberto Longhi, and of numerous artists including Guttuso and Manzù and Morandi, helping to decree his international success. He was the author of a number of publishing projects and a supporter of writers such as Gadda, as well as of numerous initiatives for the enhancement of cultural heritage: fundamental, for example, was his help in the purchase of the Pietà Rondanini and the creation of the Roberto Longhi Foundation for the Study of Art History.

For the Bank’s patrimony, he purchased Boldini’s Portrait of Giovanni Fattori painted in 1933, which was followed by Gaspar van Wittel’s Largo di Palazzo in Naples, both of which are on display in the exhibition. Instead, from the Abbey of Chiaravalle comesAngel of the Resurrection, a poignant sculpture by Giacomo Manzù, the sculptor’s tribute for the burial of his friend Mattioli.

The new appointment at the Gallerie d’Italia is thus attested as a pleasant review that consists of important loans and a few masterpieces, enhanced by an evocative setting; the reflection brought forward on bankers in the role of patrons is also interesting; on the other hand, the eleven sections of the exhibition do not seem to be equal in quality and depth, and indeed sometimes it seems to us that the discourse remains all too epidermic and generalist, in contrast instead to the rich and well-done catalog. Moreover, it seems far too arbitrary to want to present these figures of extraordinary but absolutely complex caliber only in their positive sense, forgetting how some of them conducted unscrupulous collecting, with operations sometimes bordering on legality.

For example, the catalog barely mentions the controversies between Roger Fry and John Pierpont Morgan, merely reporting how the English art historian judged the banker’s crude collecting taste, but omitting the criticisms made regarding the intentions of ’spirit that moved the tycoon in his economic transactions; in fact, Fry recalls him “so puffed up with pride and a sense of his own power that it does not even occur to him to think that others have rights.” It is noteworthy, moreover, that the essay in the catalog starts from this negative judgment in an attempt to refute it.

In short, if the intention is to respond to the reputational crisis that has plagued banks in our contemporary times by proposing a path connoted by the noble fathers, perhaps it would have been more genuine to highlight its controversies as well. Lastly, it would have been interesting to find out through the exhibition whether and in what way those who decide to invest munificently in art can still be found in the banking sector today, in order to ward off that negative judgment of being “senescent minors” that Mattioli addressed to those financiers who did not contribute to the progress of civilization and the cultural development of society.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.