Van Dyck between Genoa and Palermo: small but significant Genoese exhibition

The movement of works by great artists kept in permanent collections, especially when it comes to sending them to temporary exhibitions, is increasingly becoming a political operation before it is a scientific one. The underlying reason is quickly stated: a museum that deprives itself of one of its symbols inevitably loses some of its appeal, if only for a few months. And the fact that occasions are multiplying when a wide variety of subjects are calling on museums for the purpose of asking for works on loan (but this is not necessarily a good thing: we notice it from the quality of certain exhibitions) has led lenders to take the necessary precautions: in other words, to ask for adequate compensation in order to compensate for the loss. I lend you a Vermeer, and you send me a Michelangelo. I grant you a Piero della Francesca, however, you guarantee me a Caravaggio. When the name at stake is of a certain stature, it almost always works that way now. However, it is difficult to turn “compensation” into a real, quality exhibition that avoids taking on the appearance of a mere ostension. Well: at the National Gallery of Palazzo Spinola, in Genoa, they have been able to take advantage of an exchange belonging to the genre specified above to create an interesting opportunity for in-depth study.

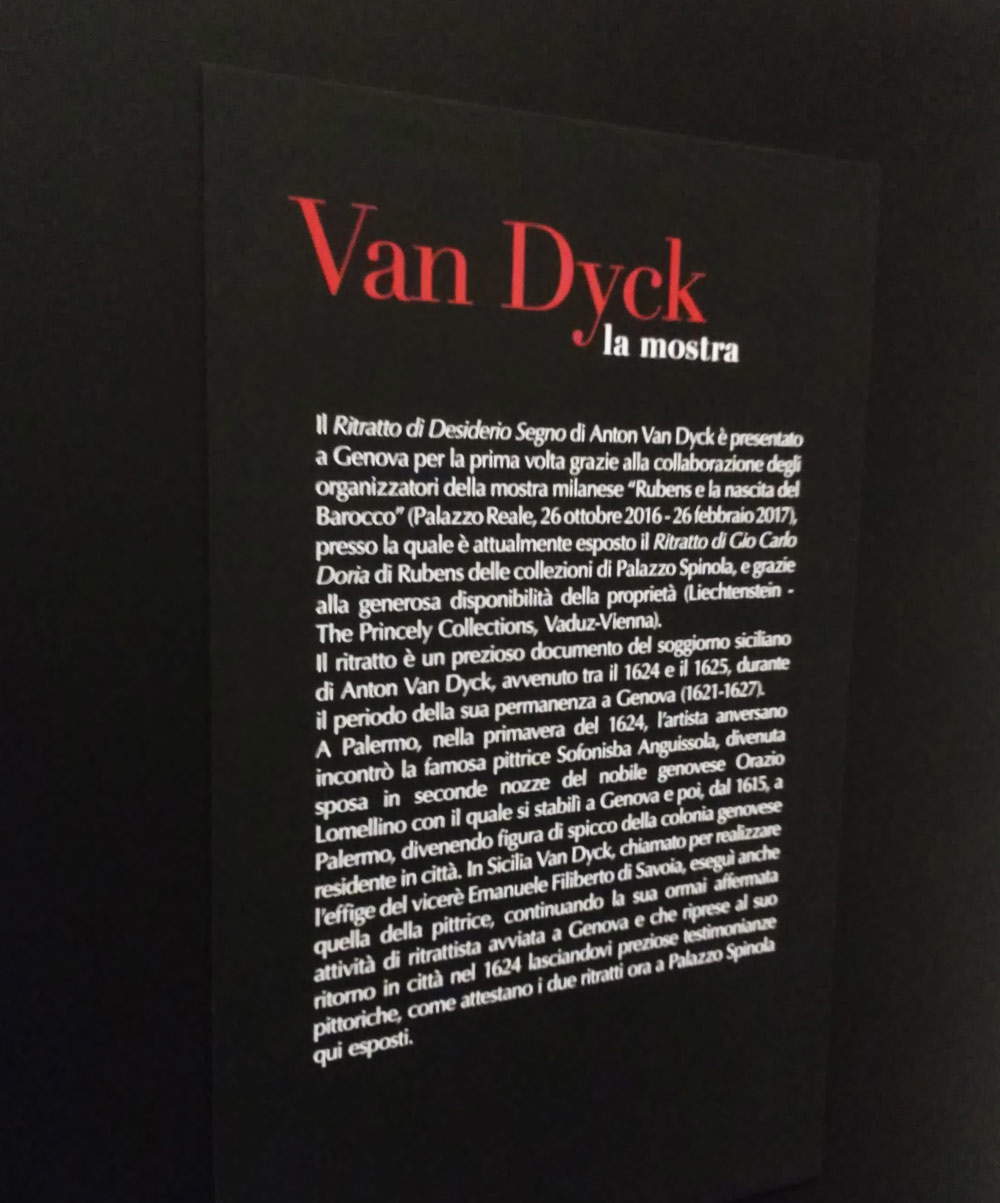

This in-depth opportunity is an exhibition entitled Van Dyck between Genoa and Palermo, which will remain open until February 26, and which has been able to take good advantage of the departure of one of the most illustrious masterpieces of the National Gallery of Palazzo Spinola. Indeed, the Gallery had to deprive itself of Pieter Paul Rubens’ portrait of Giovanni Carlo Doria on horseback, among the collection’s most celebrated works, in order to send it to the Milan exhibition on the great Flemish artist. The organization of the Palazzo Reale’s exhibition on Rubens therefore brought to Palazzo Spinola a painting that could fill the gap: from the collections of the princes of Liechtenstein, a portrait by Anton van Dyck (Antwerp, 1599 - London, 1641) thus arrived on the shores of the Ligurian Sea. It depicts a blond-haired gentleman with a curled moustache and calm, relaxed, almost lost blue eyes. Critics have long identified the subject with a merchant of Genoese origin who in 1624, the year to which the work dates (this is a dated painting), was in Palermo, where he had just been appointed consul of the Genoese nation: a sort of representative of the large Ligurian community that inhabited the Sicilian city. His name was Desiderio Segno, and we know that van Dyck made a painting depicting him because, in the inventory of goods belonging to the merchant drawn up after his death (in 1630), a portrait made by the Antwerp artist was among the various objects. We do not have mathematical certainty that it is the one in Liechtenstein today (after decades of silence, the work reappears in the late 18th century in Vienna, already in the princely collections: how it got there, we still do not know), but there are nonetheless elements that strengthen the conviction. There is the date; there are the striking similarities with the portrait of the viceroy of Sicily, Emanuele Filiberto of Savoy, which van Dyck painted in the same year and which was the reason for the journey that led the artist from Genoa to Palermo; there is the gesture of the right hand, interpreted as a “sign” that alludes to the character’s surname; there are the inventories of the Segno household that show that the man owned clothing and objects similar to those we see in the painting.

|

| The Van Dyck Exhibition between Genoa and Palermo |

|

| Anton van Dyck, Portrait of Desiderio Segno (1624; oil on canvas, 131 x 101 cm; Vaduz, The Princely Collections of Liechtenstein) |

At the National Gallery of Palazzo Spinola we can therefore see a decidedly important portrait. Because the portrait of Desiderio Segno, which arrives in Genoa for the first time, not only presents us with one of the simultaneously most intense and delicate characters in van Dyck’s production, but also bears valuable witness to the relations between Genoa and Palermo in the early seventeenth century, as well as to van Dyck’s activity in Sicily, of which only three sure portraits remain to us (namely the portraits of Desiderio Segno, Emanuele Filiberto and Sofonisba Anguissola). Moreover, the work is inextricably linked to van Dyck’s paintings in the collection of the National Gallery of Palazzo Spinola, with which it has been compared. An extremely interesting and intelligent comparison: the protagonists are the Portrait of Ansaldo Pallavicino, which has climbed two floors (in fact, the exhibition is housed on the top level of the palace), and the Portrait of a Gentlewoman (or Portrait of the Marquise Spinola), which the curators of the exhibition, Farida Simonetti and Gianluca Zanelli, have placed side by side with the portrait of Desiderio Segno, creating an evocative play of gestures and glances. The works, arranged on three large black panels that occupy an entire wall (the one that usually houses the Rubensian equestrian portrait), seem to be part of a single representation, a large harmonious and scenic triptych: the gazes of the figures placed to the side converge toward the center, and the movements seem to suggest to the viewer that they embrace this apotheosis of typically Genoese sobriety (the wealthy, at the time, were required to appear in public dressed in black, exactly like the two adult effigies, to avoid unseemly ostentation).

|

| Anton van Dyck’s three portraits compared |

|

| Anton van Dyck, Portrait of Ansaldo Pallavicino (c. 1625; oil on canvas, 108 x 64 cm fragment; Genoa, Galleria Nazionale di Palazzo Spinola) |

|

| Anton van Dyck, Portrait of a Genoese Gentlewoman with Child also known as Portrait of the Marquise Spinola (1626-1627; oil on canvas, 124 x 96 cm; Genoa, Galleria Nazionale di Palazzo Spinola) |

Particularly apt is the comparison with the portrait of Ansaldo Pallavicino, painted by van Dyck around 1625 and present in Palazzo Spinola since 1650. At that time, however, the painting was still intact: it was in fact cut at later times, because in ancient times the small Ansaldo accompanied his father Agostino, who was appointed protector of the Banco di San Giorgio in 1625 (we do not know, however, what happened to the larger part of the original portrait, the one with Agostino Pallavicino, precisely). The work, which denotes the Flemish painter’s exceptional skill in depicting the tenderness and spontaneity of children (his child portraits are among the most naturalistic and truthful of the entire seventeenth century), reveals a setting quite similar to that of the portrait of Desiderio Segno, with the head almost imperceptibly turned back and the right hand producing much the same gesture. About the same period (we are around 1627, just before van Dyck returned to Flanders) also dates the portrait of the gentlewoman, who may be a member of the Spinola family: a work of no less quality than the two paintings that appear on the same wall and which together with them is distinguished by the soft rendering of the fabrics, the gracefulness of the complexions, the capacity for psychological introspection, and the refinement and care in the depiction of the jewels and decorations.

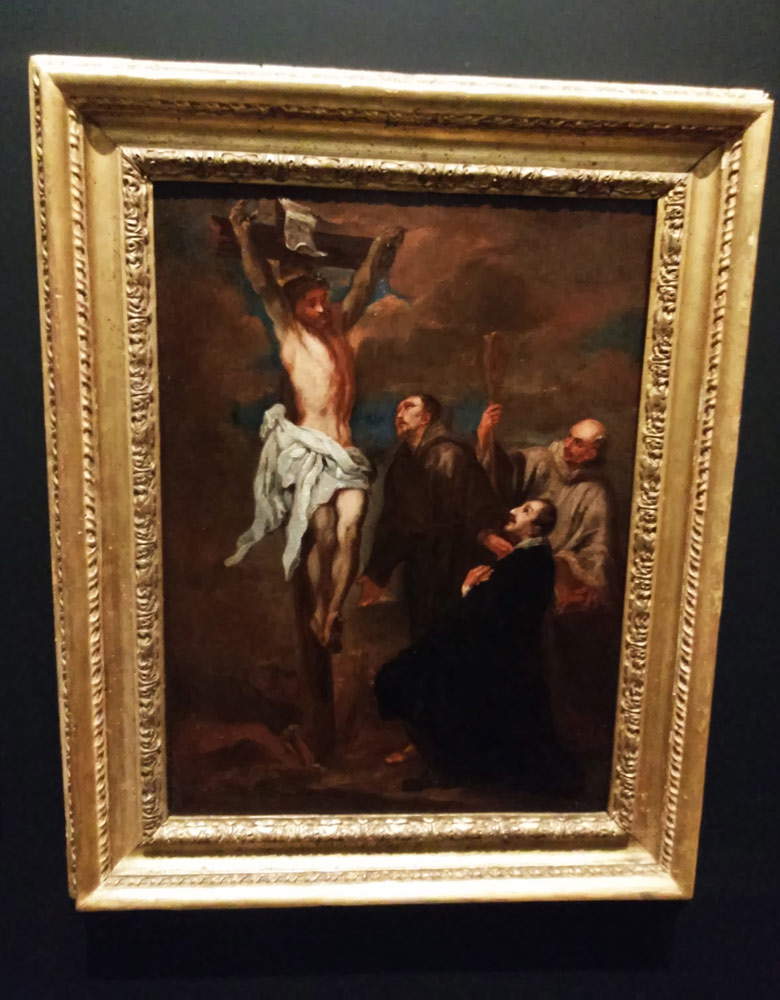

The talk is completed with a small Crucifixion, a copy by an unknown author of the original that Anton van Dyck painted for the church of San Michele in San Michele di Pagana, a hamlet of Rapallo, which is still in situ. In San Michele di Pagana, a wealthy Genoese perfume merchant, Francesco Orero, owned a villa, and it was he who wanted the work for the parish church (so much so that he had himself portrayed in adoration of the crucifix): the work on display can almost be seen as a symbol of van Dyck’s insertion into Genoese high society circles, with which he had become particularly familiar. In fact, his stay in Genoa lasted from 1621 to 1627 (if we exclude the brief interlude in Palermo, during which the artist nonetheless continued to frequent Genoese patrons), and during his stay, in addition to several portraits, the artist painted works of various subjects, and the Crucifixion for the Riviera town is one of the main ones. The work could also serve as an introduction to the exhibition, to better frame the historical context to which the exhibition refers and to convey to the visitor van Dyck’s importance to the Genoese milieu (as well as the Genoese milieu to van Dyck): its presence is thus yet another small touch by the curators, who with just four paintings have managed to put together a very dense and meaningful exhibition.

|

| Anton van Dyck (copied from), Francesco Orero in Adoration of the Crucifix in the Presence of Saints Francis and Bernard (first half of the 17th century; Genoa, Galleria Nazionale di Palazzo Spinola) |

|

| One of the panels of the exhibition |

Also of note is the catalog, published by SAGEP, in the now classic and handy 17 x 22 format that the publishing house has adopted for its Palazzo Spinola publications. There are four contributions, all of the highest caliber: starting with the fine essay by Xavier F. Salomon, curator of the Frick Collection in New York and one of van Dyck’s leading experts, on the painter’s Palermo sojourn and the portrait of Desiderio Segno. This is followed by a very up-to-date contribution by art historian Matteo Moretti (who is also the author of the exhibition’s excellent captioning apparatus) in which, following an investigation that began with an analysis of the Historical Archives of Palazzo Spinola, he takes stock of a conspicuous number of works in the Gallery that documentary sources refer in various ways to the Flemish painter. The essays on the portrait of Ansaldo Pallavicino and the portrait of the Marquise Spinola, on the other hand, are authored by the two curators, Farida Simonetti and Gianluca Zanelli, respectively.

Van Dyck between Genoa and Palermo is a short review that finds its raison d’être in several reasons. The presence of a portrait that makes manifest the relationship between the two cities, perhaps little known to the general public, and that allows us to have in Genoa a fundamental testimony of van Dyck’s artistic activity linked to Genoese patronage. The possibility of seeing three examples of the painter’s portraiture belonging to the last phase of his Ligurian sojourn close to each other (the Palermo interlude can be considered almost an integral part of it, since van Dyck continued to maintain relations with Genoese clients). The opportunity to reconstruct, on the basis of the most recent studies and archival research, and consequently present to the public through the catalog, the history of the nucleus of Palazzo Spinola works referred to van Dyck. The possibility of having a portrait that helps the visitor focus on the stylistic choices of the Flemish painter. The popularizing intent, stated in the opening of the catalog, I believe has been fully satisfied. On the scientific level, we have no sensational novelties, but we have many useful elements (among which it is worth mentioning a proposal “purely by way of working hypothesis” by Matteo Moretti for the identification of the gentlewoman protagonist of the Portrait of a Lady once referred to van Dyck, and traced recently, by Piero Boccardo, to the hand of Jan Roos, van Dyck’s collaborator in Genoa) that will surely advance the state of knowledge on the art of Anton van Dyck, of which the exhibition at Palazzo Spinola already constitutes a further important piece.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.