by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 15/07/2018

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'Andrea Bianconi. Fantastic Planet. Inferno Purgatorio Paradiso', at CAMeC (La Spezia), from June 23 to September 30, 2018.

For Andrea Bianconi (Arzignano, 1974) everything has a direction. When we walk, think, discuss, eat, sleep, make love, perform the simplest of daily actions or plan the most complex decision of our lives, we move following a direction. We walk guided by an arrow, to use perhaps the most characteristic symbol of Andrea Bianconi’s imagery and figurative repertoire. An arrow, because perhaps no other sign better than it is able to refer metaphorically to the constant dialectic between freedom and constraint. The artist had matured these reflections years ago, in New York City: he recounts that they were oppressively hot days, the house was a kind of oven, the always open windows looked out onto the Port Authority bus station, and he could see people coming in and out of the station at all hours of the day. “An overlay of lives, a map in constant construction and deconstruction, in constant transformation.” Bianconi imagined people as arrows: free to choose a direction, but obliged to respect it (after all, one has never seen an arrow that does not respect its direction). From those ideas was born Traffic light, a performance presented in 2008 in Houston for the first time (but, it must be specified, mere repetitions are a rare if not impossible thing in Bianconi’s art: he suffers them as a limitation). It was one of the first occasions in which the arrow had a leading role.

His new solo show, at CAMeC (La Spezia), is all about moving around following arrows in search of that Fantastic Planet that gives the exhibition its title. Fantastic Planet: two words that had entered, almost overwhelmingly, into Andrea Bianconi’s mind as he, simply, drew arrows. “I was drawing directions of looks and directions of languages,” he said, “I kept looking for unique looks and few words.” When the two words appeared: Fantastic Planet. He began writing them in succession and obsessively, they became the subject of a performance that was also held in Houston, in 2016, and of an exhibition that closed in Milan last week. Here, in the spaces of the Nuova Galleria Morone, visitors were invited to sit on a stool in the center of a room whose walls had been covered with the two words Fantastic Planet written continuously over almost the entire surface of the wall. The objective was to spur them to wonder if their Fantastic Planet somewhere existed, and then to search for it. To undertake, in essence, a kind of journey into themselves.

And it is Andrea Bianconi himself who presents his La Spezia exhibition as a journey. But there is none of the rhetoric of the many artists who, running out of ideas, fall back on the easy theme of travel. The exhibition of the Venetian artist is extremely coherent with his artistic path, it is the continuation of an itinerary already traced, it is a summa of different experiences, it is a set of suggestions proper to an educated artist: there is the stream of consciousness of Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, there is the homage (made explicit in a 2016 exhibition) to Alighiero Boetti and his Mettere al mondo il mondo, there can be found the paradoxes of Beuys, the Sartrian concept of freedom (one cannot demand one’s own freedom if one does not also want that of others), the oddities and independence of the group Co.Br.A. (especially Alechinsky), the researches of the sign painters from Capogrossi onward. And of course there is the reference to Dante’s Commedia, if only because Bianconi’s Fantastic Planet passes through Inferno, Purgatorio and Paradiso.

|

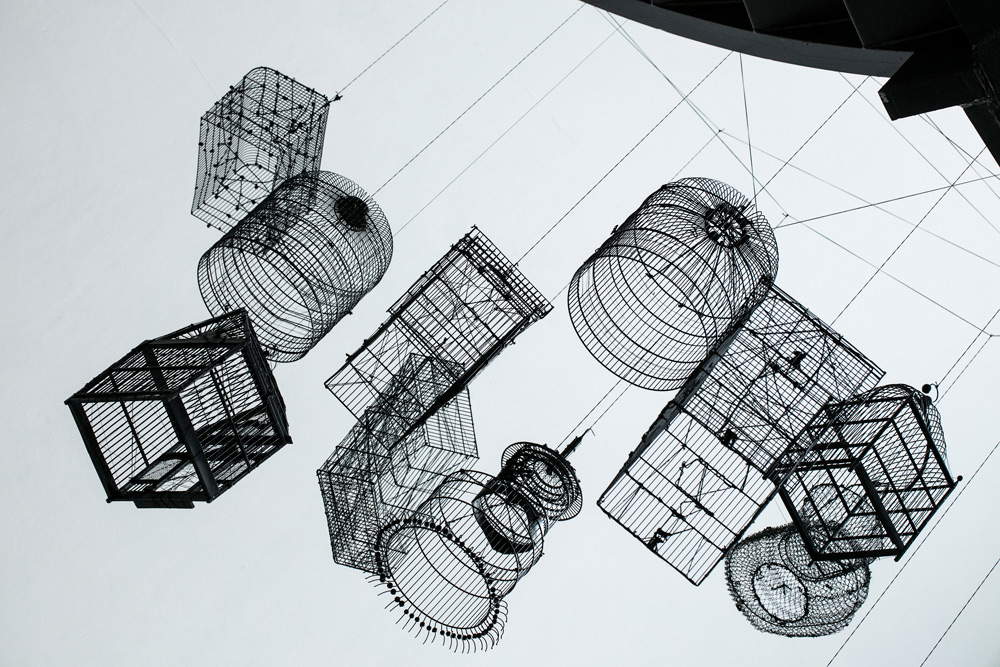

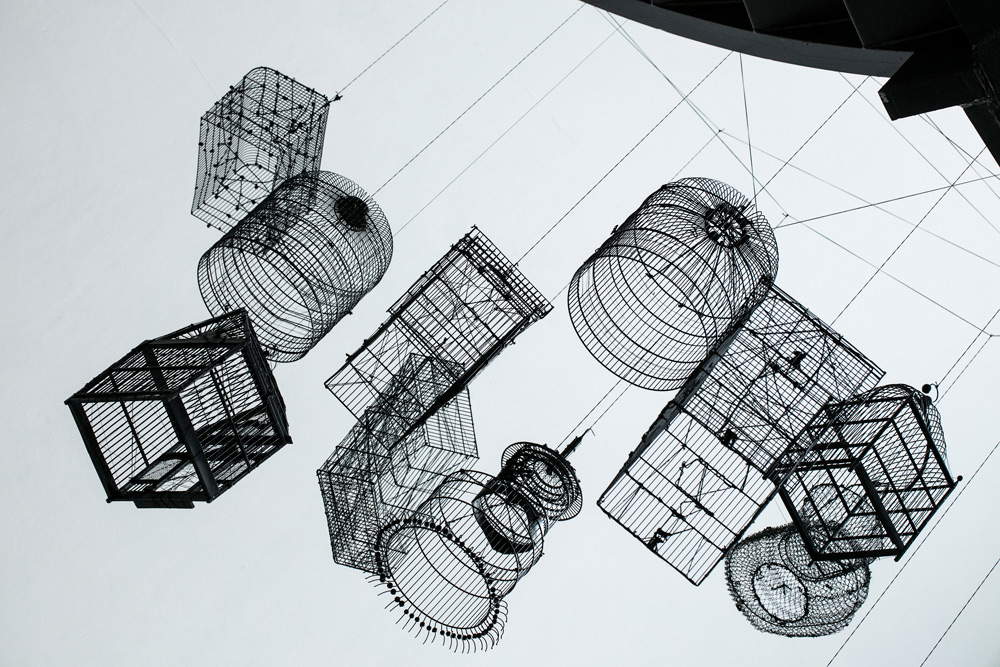

| Andrea Bianconi, Trap for clouds (2011; installation with cages, dimensions variable; courtesy AmC Collezione Coppola, Vicenza). Ph. Credit Enrico Amici |

|

| View of the hall of hell at the Fantastic Planet exhibition (La Spezia, CAMeC) |

|

| View of the hall of heaven at the Fantastic Planet exhibition (La Spezia, CAMeC) |

Bianconi’s play, however, starts from quite different assumptions than Dante’s. There is no straight path from which to stray: the alternative, for the Venetian artist, is always an opportunity. “In Andrea Bianconi’s work,” wrote the curator of the exhibition at CAMeC, Vittoria Coen, “one perceives a continuous force that is open to possibilities, to changes, that in the course of our lives we are involved in. Without any preconceptions, the artist leads us, step by step, in a direction, but also proposes an alternative.” So too, Bianconi’sInferno is not a hell similar to the horrific and violent one we might imagine: it is, if anything, a kind of existential hell. It is the anxiety brought about by our everyday reality, it is the doubts that assail us during our daily lives, it is our hesitation in facing certain choices, it is the darkness within which we often move: everything in Bianconi’s inferno tends to communicate this aspect, starting with the large black paintings that symbolize our blindness but which, when seen up close against the light, reveal a dense web of arrows (signifying that even in the deepest night there is still a direction to follow), there are the maps made of everyday objects trapped under pours of gray paint (scissors, buttons, rings, squares, rulers, toy cars and electric trains), there are the cages that the public gets to appreciate on the stairs of the CAMeC with the dreamy installation Trap for clouds (“Trap for clouds”), and which are typical of the artist’s language (visitors are reflected in the mirrors Bianconi has placed there, with the result that they really find themselves caged in), and there is also Too Much, the singular sound installation that sums up the seven songs that have underscored important moments in Andrea Bianconi’s life (for the record: Pavarotti’s Nessun dorma performed by Pavarotti, Domenico Modugno’s Meraviglioso, Bob Dylan’s Blowin’ in the wind, Gloria Gaynor’s I am what I am, Michael Jackson’s Man in the mirror, Eugenio Finardi’s Extraterrestre, and Aretha Franklin’s I say a little prayer ). All brought together in a single track to try to see if all the moments of one’s life can come together in a single moment. The effect is alienating: exactly like when we think of so many memories all at the same time.

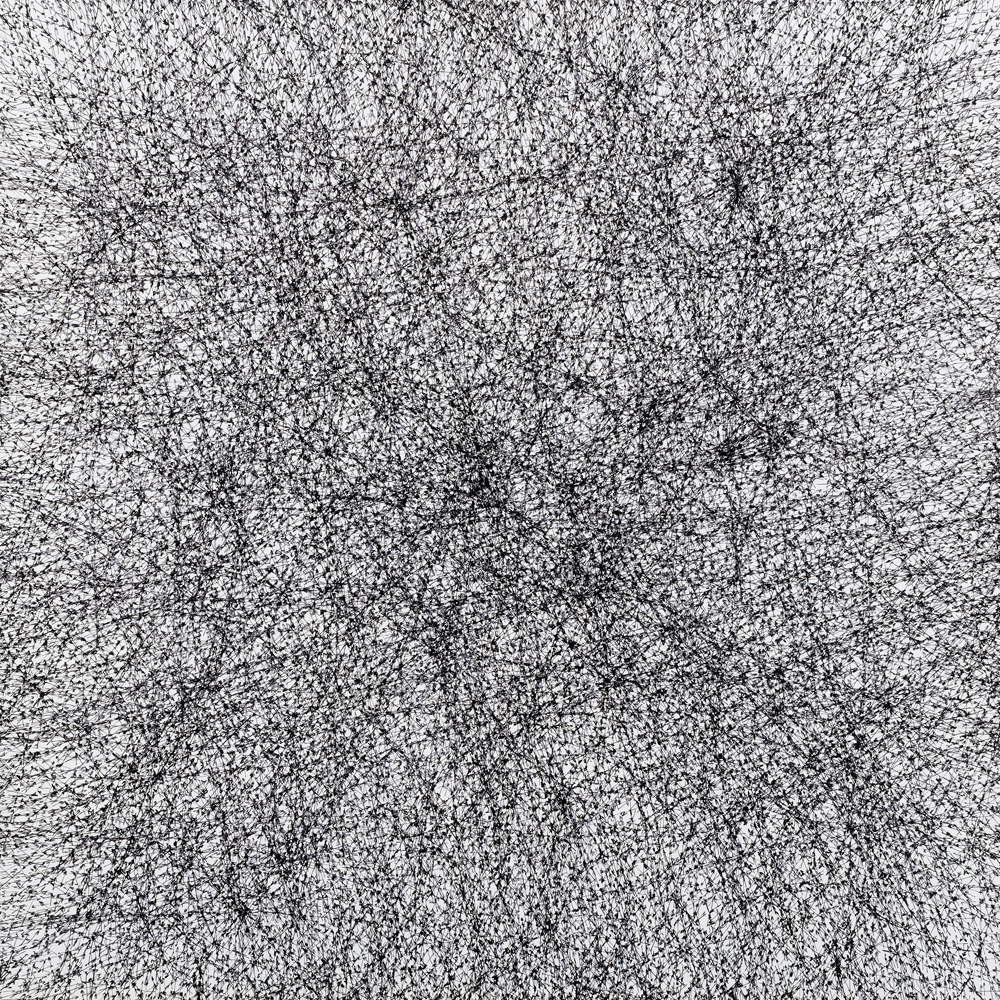

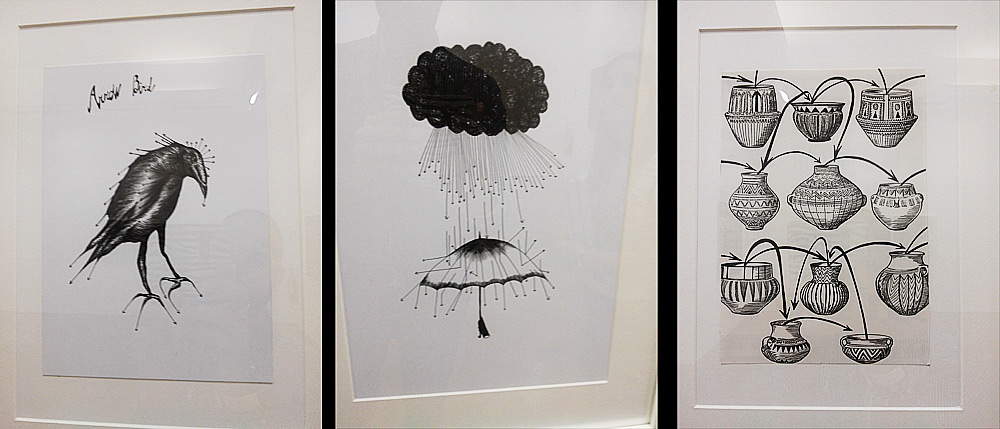

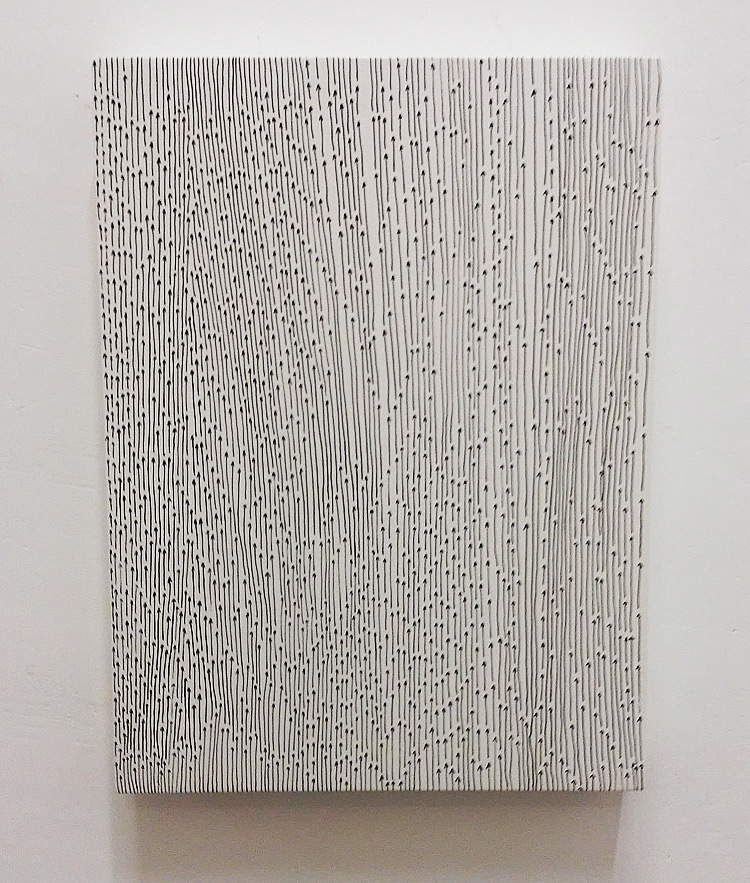

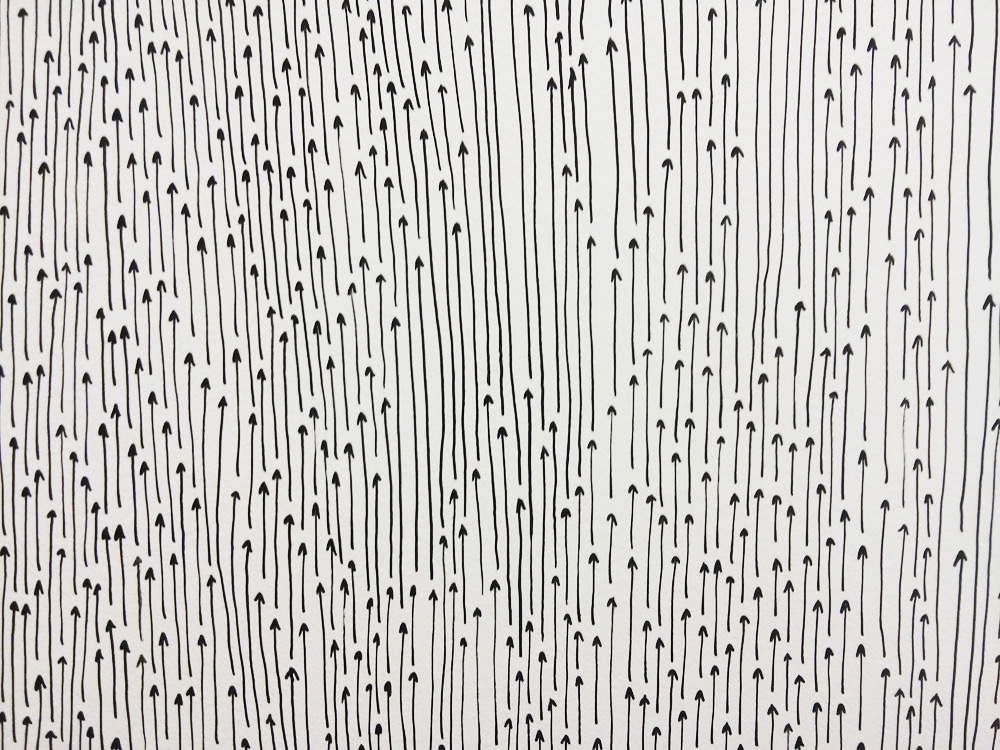

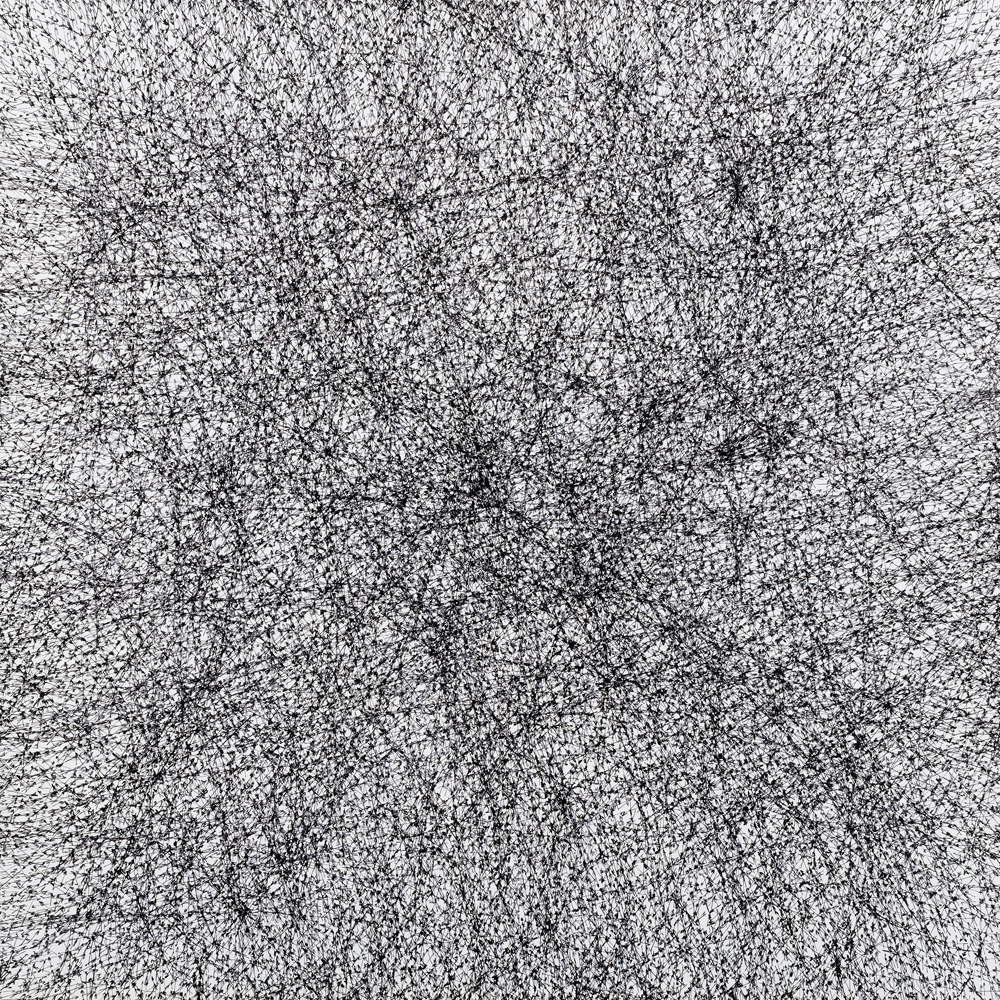

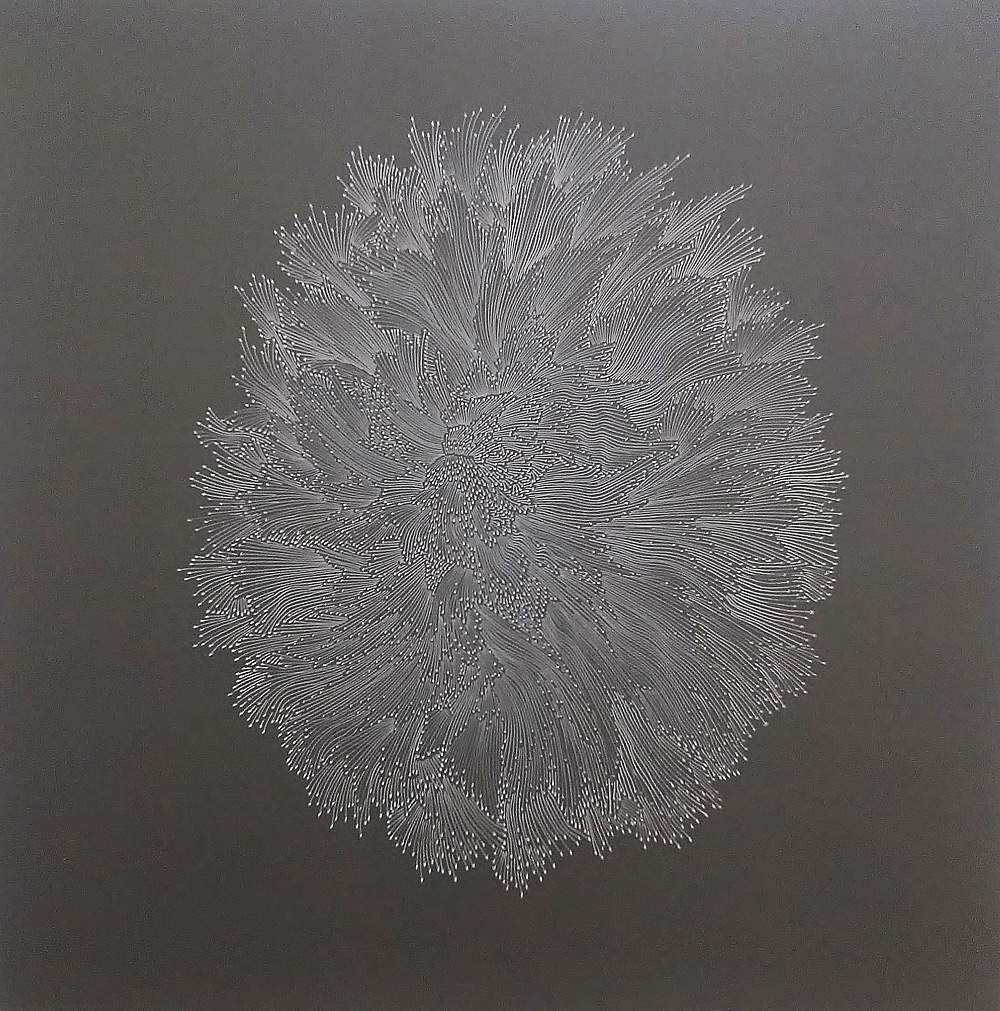

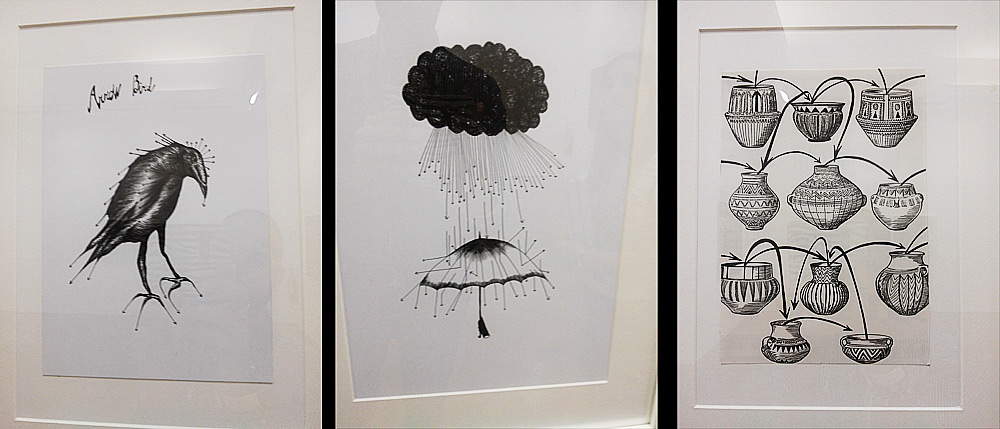

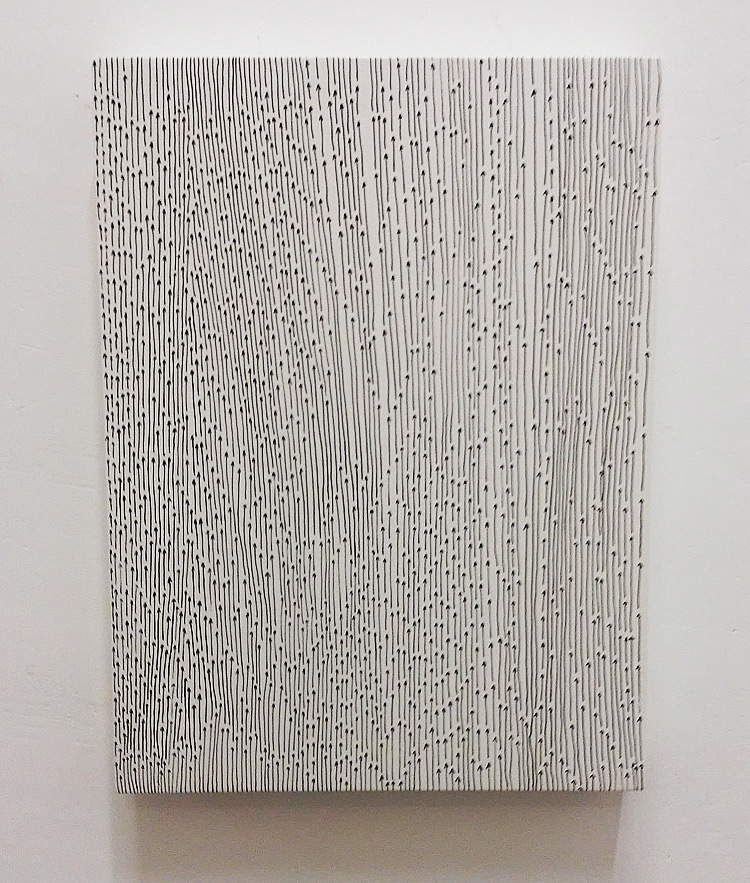

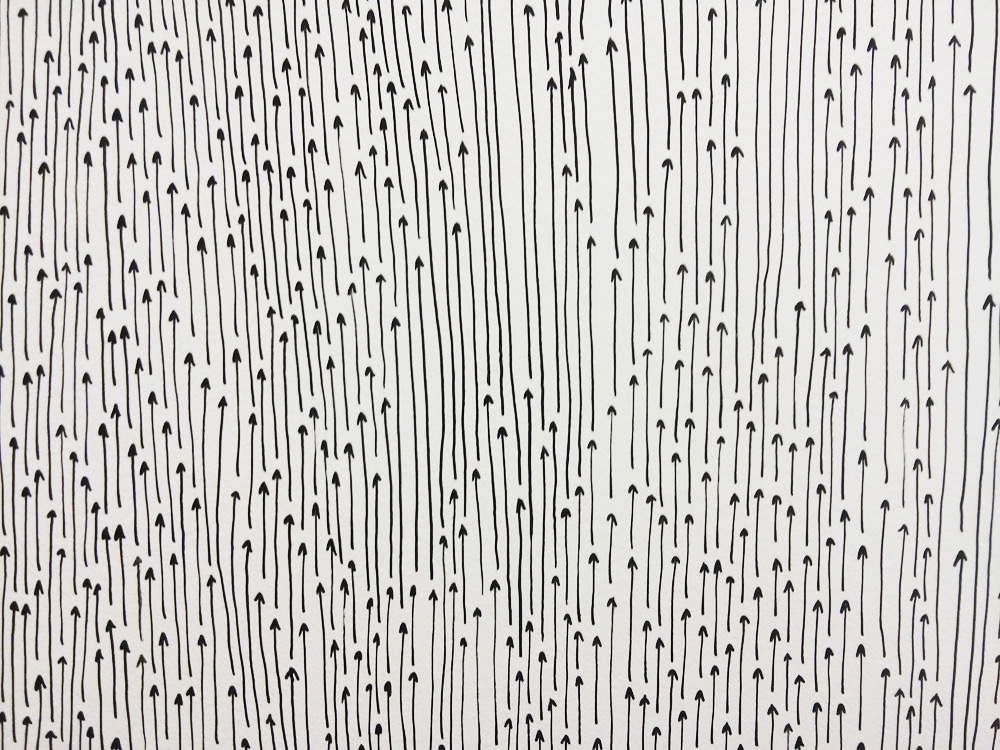

In the next room we move on to purgatory. Black is abandoned and gray arrives: in Bianconi’s easy symbolism, it is the color of suspension, of the middle ground, of stalemate. It is the place where drawing triumphs, a practice that lies somewhere between the idea and the finished work. An entire wall is filled with the drawings to which Bianconi has entrusted his ideas: feathers and fish in the form of arrows, vessels that communicate, arrows that transform, incredible spider-arrows, even a poem dedicated to the arrow. “Drawing,” the artist said in an interview with Catherine de Zegher in 2017, “is the beginning, the path, the journey. I draw all the time, everywhere. I often find myself drawing while talking. In my life, drawing is like drawing a series of concentric circles, it involves everything, it is construction and deconstruction.” But that’s not all: drawing “allows you to make unpredictable connections,” it allows you “to find a relationship between things, between two ways of feeling or between two different cultures,” it is like “waking up suddenly and opening your eyes for the first time,” and drawing is “the child of the hand and the father of memory.” And then there are the Tunnel Cities, sophisticated canvases where Andrea Bianconi’s imaginative drive takes the form of tangles of arrows indicating the infinite directions our existence can take (and the tunnel becomes, again, a metaphor for existence itself). Finally, a white canvas with black arrows, all pointing upward, indicates, at the end of the journey, the direction to heaven.

|

| Andrea Bianconi, In Between (2014; cage and mirror, 69 x 43 x 45 cm; courtesy Barbara Davis Gallery, Houston TX, USA). Ph. Credit Enrico Amici |

|

| Andrea Bianconi, In Between (2013; cage and mirror, 158 x Ø 30 cm; courtesy Dream Collection, Vicenza, New York). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Andrea Bianconi, Map 13, detail (2013; mixed media on canvas, 180 x 145 cm; private collection/private collection, Verona, Italy). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Andrea Bianconi, Too much (2015; photography and audio, 54 x 44 cm; courtesy Dream Collection, Vicenza, New York). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Andrea Bianconi, Purgatory (2018; ink on canvas, 90 x 90 cm; courtesy Barbara Davis Gallery, Houston TX, USA) |

|

| ndrea Bianconi, Tunnel City Grey (2018; ink on canvas, 100 x 100 cm; courtesy Barbara Davis Gallery, Houston TX, USA) |

|

| Andrea Bianconi, Tunnel City Grey, detail |

|

| Some drawings by Andrea Bianconi |

|

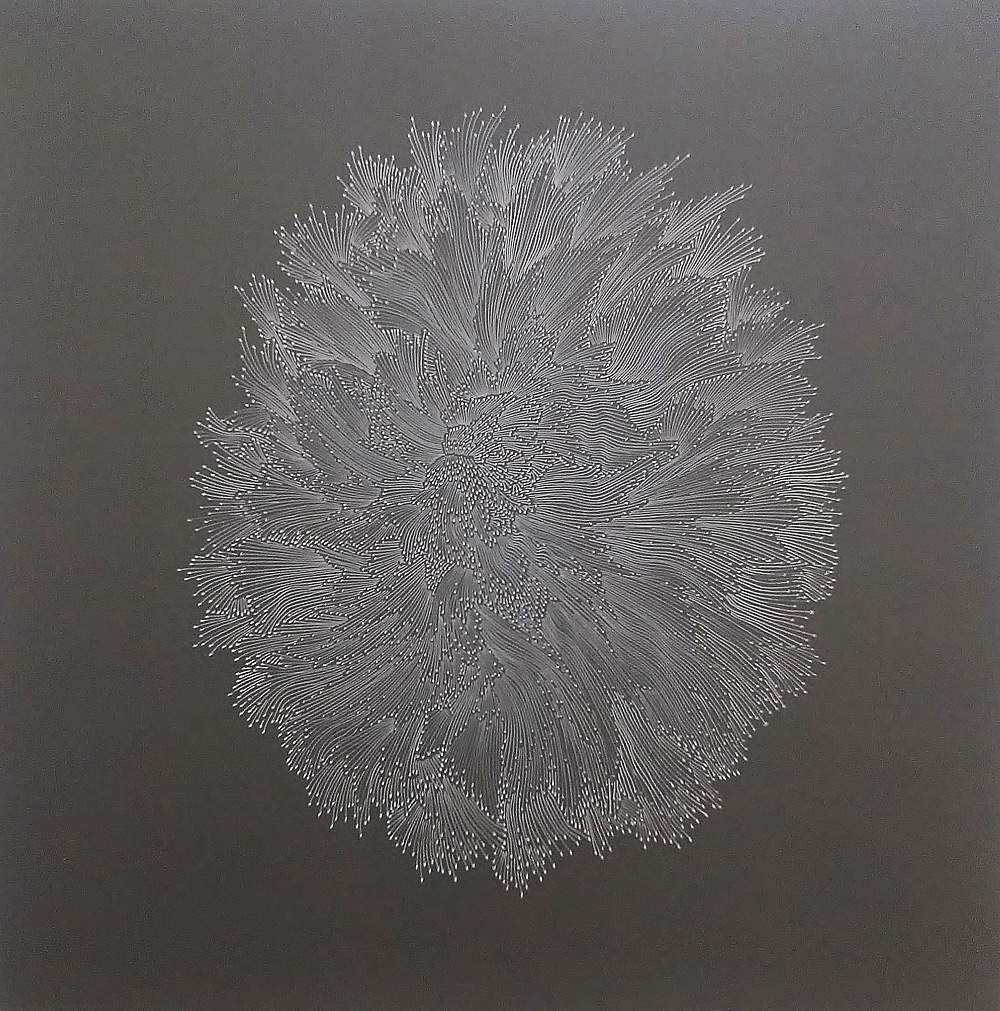

| Andrea Bianconi, ( Paradise) (2018; ink on canvas, 40 x 30 cm; courtesy Barbara Davis Gallery, Houston TX, USA) |

|

| Andrea Bianconi, (Paradise ), detail |

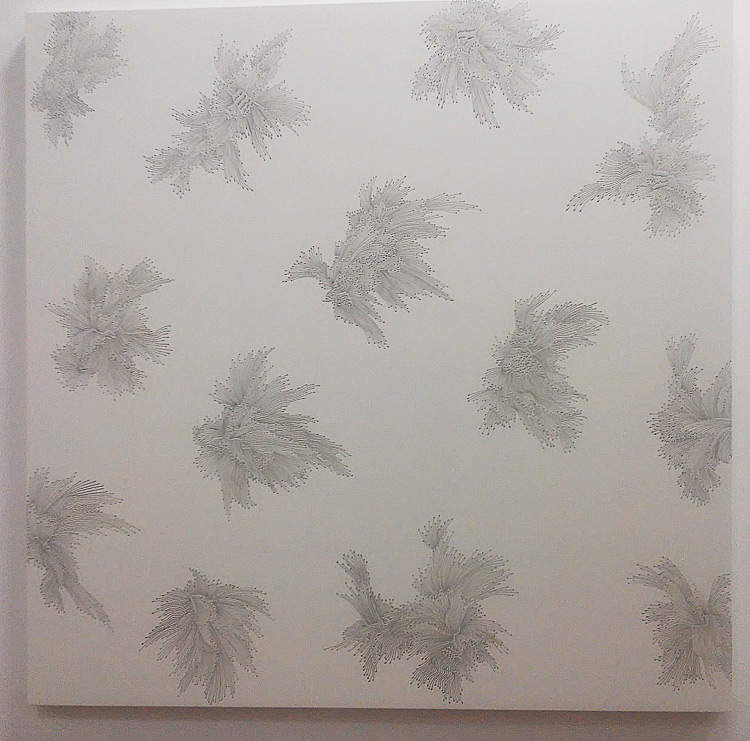

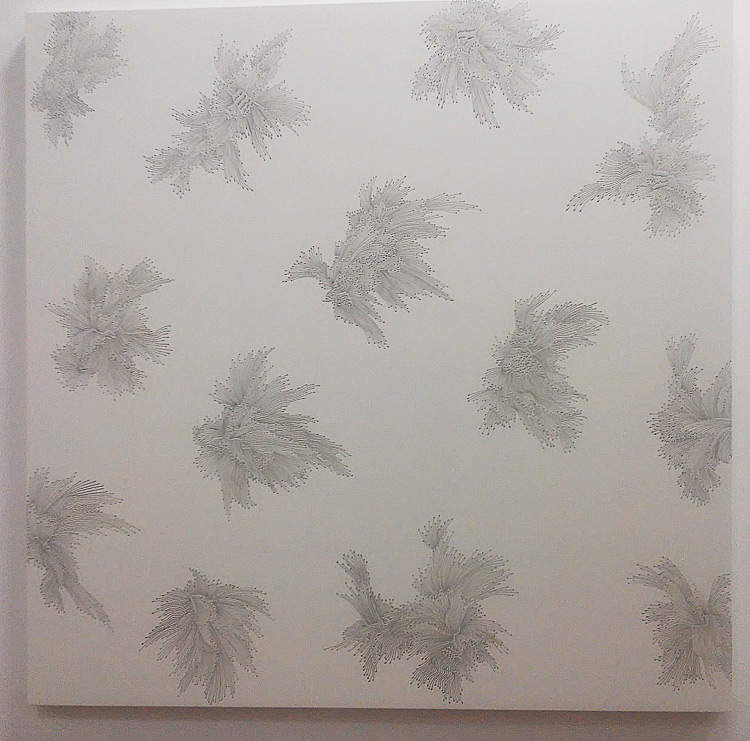

And Paradise appears, finally, in the next room. Visitors are greeted by a large wing: Bianconi plays on the fact that the term for drawing in English, drawing, contains the word wing, “wing” (drawing is therefore movement and freedom). The wing is the only element with religious connotations in the empyrean of the artist from Vicenza. In fact, we find ourselves in a world in which harmony is guaranteed by themeeting of opposites generated by his Earthly Paradises, canvases where arrows collide, find each other, run away, chase each other, meet in a whirling movement that the artist has traced with his eyes closed, by instinct, as if to return to a primordial dimension in which the sign becomes almost a product of the unconscious, of the artist’s deepest feeling. Here, then, Paradise becomes anything but the final destination of the journey: it is a place of creation and meditation, representing nothing more than a further stage in the journey of knowledge undertaken by the artist.

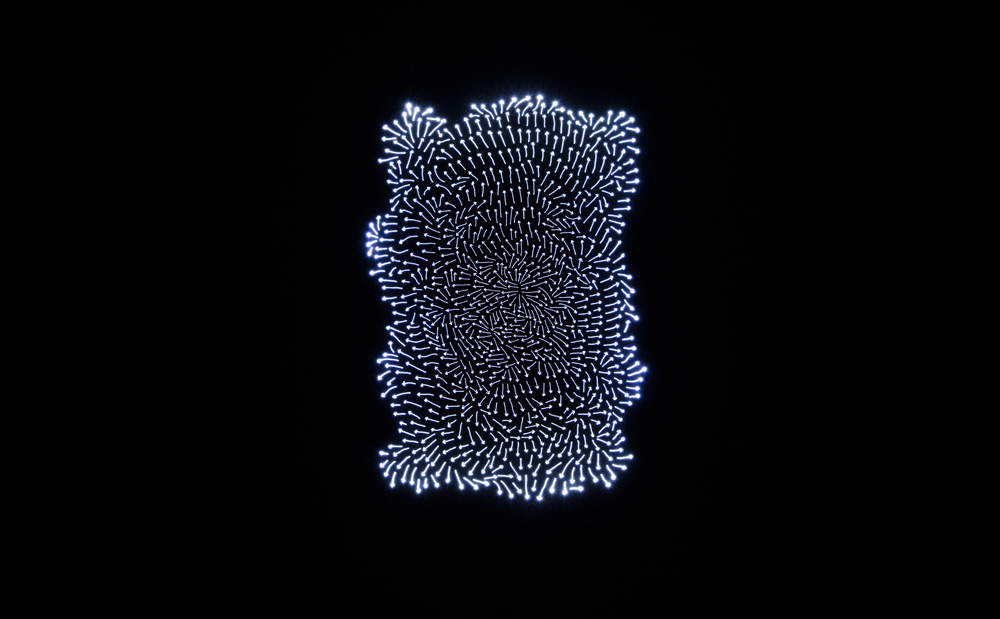

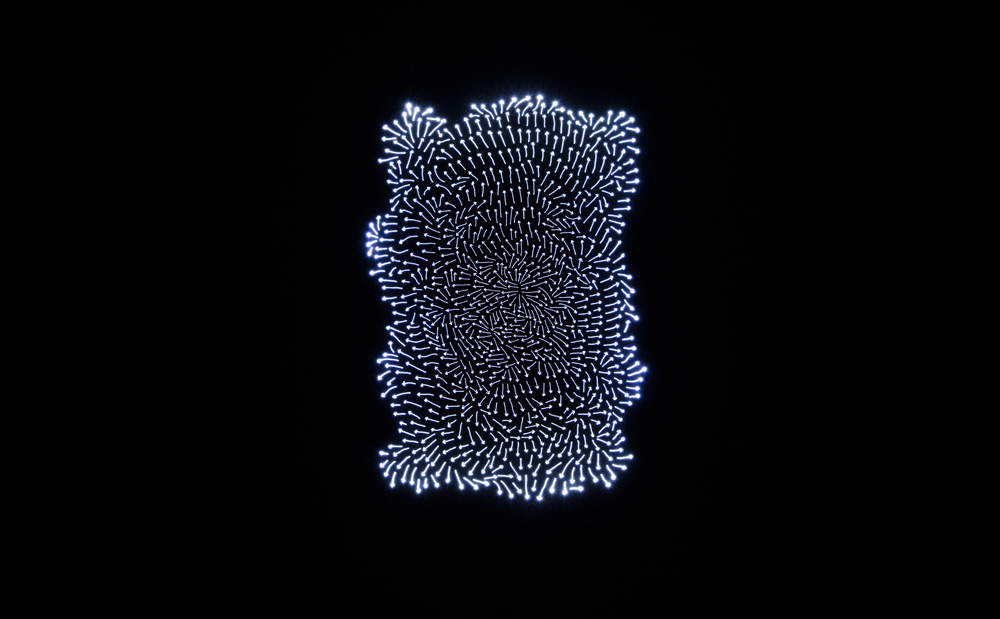

A journey that, at the end of the exhibition, after having made us appreciate the imposing wall drawing, a large site-specific wall drawing that is almost a sort of summary of the journey between the three otherworldly worlds, takes us inside a completely dark room to propose a new journey, this time within ourselves. We are alone, in a decompression chamber, we cannot look anywhere because everything is dark: there is only, at the back of the room, an aluminum lightbox carved with a myriad of arrows(City Map) that invites us to look inside ourselves in the darkness and silence of the room. We turn around, and at the back of the room the Hole installation makes the “map” appear behind us, as if it is illuminating us, as if we have found our direction. The effect is almost irreproducible in photography: one must go live to see it.

|

| Andrea Bianconi, Earthly Paradise 2, detail (2017; ink on canvas, 80 x 70 cm; courtesy Barbara Davis Gallery, Houston TX, USA) |

|

| Andrea Bianconi, Drawing 1 (2018; ink on canvas, 150 x 150 cm; courtesy Barbara Davis Gallery, Houston TX, USA) |

|

| Andrea Bianconi, Where (2018; ink wall drawing 54 X 861.5 cm). Ph. Credit Enrico Amici |

|

| Andrea Bianconi, City Map (2017; aluminum lightbox, carving, 192 x 142.5 cm; courtesy Dream Collection, Vicenza, New York) |

|

| Andrea Bianconi, Hole (2018; ink on framed mirror, 66.5x57 cm; courtesy Barbara Davis Gallery, Houston TX, USA) |

Where, then, is Andrea Bianconi’s Fantastic Planet? The artist leaves the answer to visitors. “His Fantastic Planet,” writes Vittoria Coen, “is also a question mark, a questioning that the artist addresses to himself and to all of us [...]. Bianconi urges us, exhorts us, almost, to question ourselves, in a relationship of cause and effect in which the work appears as an ecosystem, a place, rich in propositions and propositions that goad us [...].” Andrea Bianconi’s Fantastic Planet is encounter and clash, idea and concreteness, dream and reality, it is an infinity of possibilities, it is linked to the dimension of memory but is deeply rooted in the present and is a spur for the future, it is experience, it is beauty and ugliness. In essence, in Andrea Bianconi’s Fantastic Planet, “everything is art and everything is life,” also because perhaps there is not just one Fantastic Planet: probably, fantastic planets are infinite. Anyone who looks at one of his works will surely find reasons to recognize themselves in his Fantastic Planets, or find a trigger to get to (or return to) their own Fantastic Planet. His works deeply involve the relative, they manage to establish a fruitful dialogue with the viewer, they take the viewers by the hand and manage to initiate an extraordinary, delicate process of identification.

This is also because Andrea Bianconi’s art is easy, simple, to the point of bordering, but only on the surface, on banality (because in reality his is a cultured and profound art). And it is, at the same time, an art endowed with great inner strength and, above all, great concreteness: Bianconi is not a faint-hearted dreamer living in castles of clouds, but an artist perfectly aware that there is a daily reality with which to come to terms. Of course: Bianconi certainly would like to live outside of reality. But this is impossible, for him as for everyone: art is therefore, for Bianconi, not a way to elevate reality, as other artists have tried to do, but a way to protect himself from reality (even cages fulfill this symbolic function of protection: the example is that of libraries that hold ancient volumes) and, above all, to try to improve it. This is perhaps the highest sense of Andrea Bianconi’s art.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.