Andrea Baboni celebrated in Correggio with a valuable and fascinating exhibition

Curated by Francesca Manzini and Francesca Baboni, the city of Correggio honors with an exhibition(Viaggio tra Otto e Novecento. The Andrea Baboni Collection: a creative journey between painting and collecting) its illustrious son Andrea Baboni, born in 1943, whose studies have nourished the entire international culture by enhancing and revealing the extraordinary heritage of nineteenth-century Italian painting. In the incipit of his independent life, this attentive and highly sensitive young man became part of the artistic tradition of the small capital of the Po Valley - once the home of the great Allegri - and approached well with the strong personality of Carmela Adani (1899-1965), an admirable sculptor and painter herself, who had carried out studies and works of considerable stature in Florence, first inheriting the marble practice from Giovanni and Amalia Dupré, and then jousting with the formal freedoms of Graziosi.

Drawing and painting, as will also be seen in the exhibition, Andrea carried out a careful examination of his own personality in order to fully understand the aptitudes he possessed, to which he added the certain fascination of the capital of the arts, and all of which made him choose the faculty of Architecture in Florence: a distant location and a university line hitherto never attended by a fellow citizen, but a singular and just idea. He perceived that the vast ray of creative possibilities and radiating contexts, which would be offered to him by architectural endeavor, would involve him in a broad and desirable enrichment of culture. And so it was! In his early returns to his homeland he would tell us about building and compositional aspects, examinations on load-bearing beams, balancing loads, bolting metal crossbeams, etc., etc.; but then, to our surprise, he began to tell us about Maggio Street (but how so?), the street where antiquarians and art dealers displayed and proclaimed paintings and prints. Among these he was particularly interested in the nineteenth-century pieces, with their character of immediate relevance, of imminent truths, of luminous natures, of enchantments no longer veiled by powders or vexatious gestures. And hence began his path as an exceptional capturer of the values of early modernity, until he became that “doctor magnus” of knowledge about the nineteenth century in an Italy that, like other countries that had now emerged from Romanticism, was reaching extreme heights of poetry and fragrance in painting.

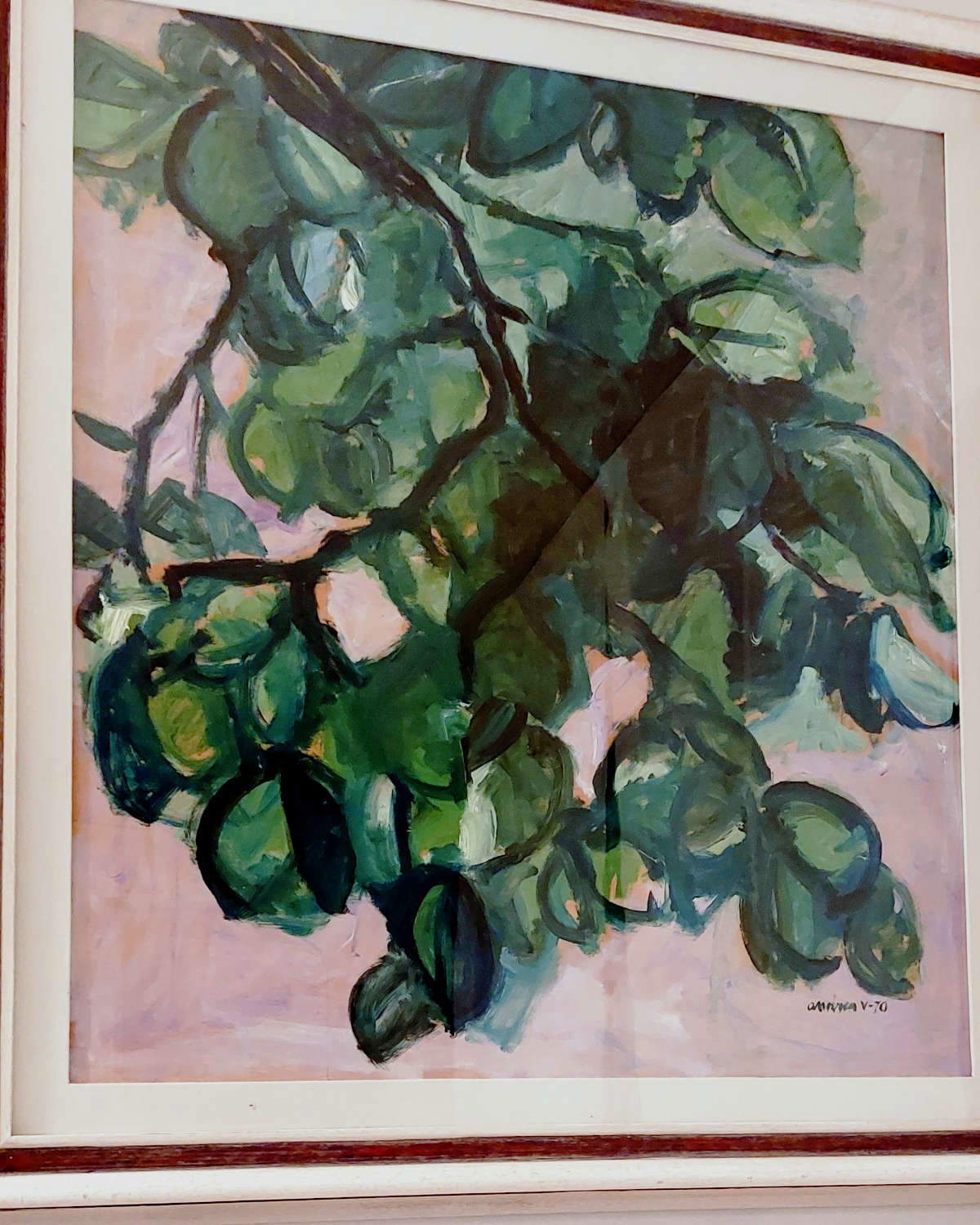

Andrea Baboni, even before and after graduation (1970) began a systematic and formidable undertaking of studies and had the merit of accompanying every observation, every even branched research, every pictorial phenomenon of the national nineteenth century, with a historical and rationally significant corollary that had never occurred in Italian criticism, and that showed in his time how that certain widespread disinterest in the century of transformations was by no means forgivable. He can be said to have determined the absolute critical-philological values of each of the artists considered during his long and still lively work of exploration concerning the masters of the century of the Risorgimento up to the enigma-filled twentieth-century gates. His personal career soon records excellent publications and critical presence at specialized reviews. He became responsible for Italy, with consultancy for the New York and London offices, for the Art of the 19th Century Department at Christie’s International Auction House, thus completing with rigorous competence that panorama of Italian painting ranging from the Accademia to the Vero, even through systematic contacts with scholars and collectors. At the same time he himself exhibits works between abstractionism and figuration, such as the well-known “Leaves,” with the beloved supervision of Adani.

Therefore, this exhibition, held aristocratically in the princely seat of his hometown, becomes the epinicium of a life, of a convincing achievement that critically sees the great Andrea as the “master of masters” for a very high Italian period: that extended nineteenth-century arc that, leaving with honor the last neo-classicism of perfect forms, arrives at the heroic naturalism of the macchia and then travels the freedoms of realistic vigor, restless verismo, and the most intimate lyricism of luminous, ecstatic and moved painters.

The exhibition presents Baboni’s early creative path as a painter and then in wide expanse the careful selection of about fifty works divided by regional “schools,” among the most important in Italy: an exhibition of national value for a century that was truly a protagonist.

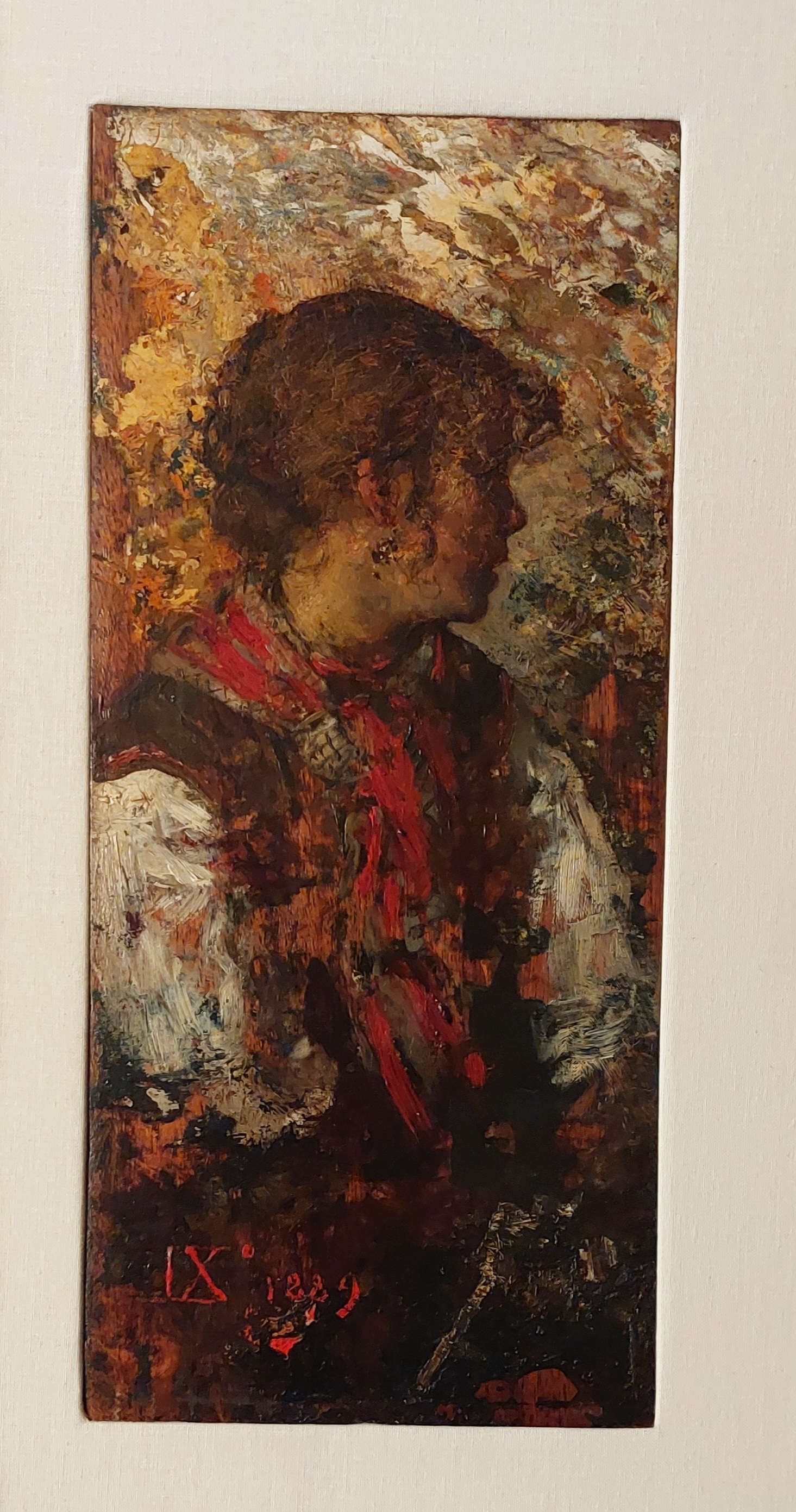

Works by Andrea Baboni

They are among the fragrant works of the young Baboni, intensely addressed to nature. The plant cycle is much more intense than the only two examples we present here, but it fully reveals the vocational address of the painter, who would later be an architect and a great scholar of the real.

Tuscan School

The Tuscan sphere was a crucible of heralds, then of artists, groups, movements, improperly called “schools,” that ferried painting from an academic education to an encounter with the real, that is, to an evident, unprepared reality, and for this very rich in prehensile and emotional impulses. Andrea Baboni was the lucid critical organizer of a process that saw at its beginnings the unexpected but very vivid trials of Gelati, Pointeau, Ademollo, and afterwards the appearance on the scene of the other “progressives” of the Caffè Michelangiolo who fulfilled the brief but dazzling experience of the “macchia” and from there the subsequent expansion of that “after the macchia” that became, with many well-known names, the admirable universe of the Tuscan mater.

Substantial body then is the Tuscan regional school, where verist painting was born with the debate held at the famous “Caffè Michelangiolo” in Florence among some young revolutionary painters. Artists who were also fighting on the front lines in the wars of independence; who wanted to revolutionize the academic rules of the time by going on to paint the countryside, the work of the fascinaie, soldiers on horseback, the rough and rugged realities of everyday life. The most prominent exponent was Giovanni Fattori, along with others scornfully called “macchiaiuoli” (Abbati, Sernesi etc.), for macchia-like pictorial draftsmanship, such as Vincenzo Cabianca, Silvestro Lega, and Telemaco Signorini, until we reach the twentieth-century dawn with Fattori’s pupil Plinio Nomellini, who would approach Divisionism in the early twentieth century, and the Leghorn artist Oscar Ghiglia, an artist much loved by Modigliani.

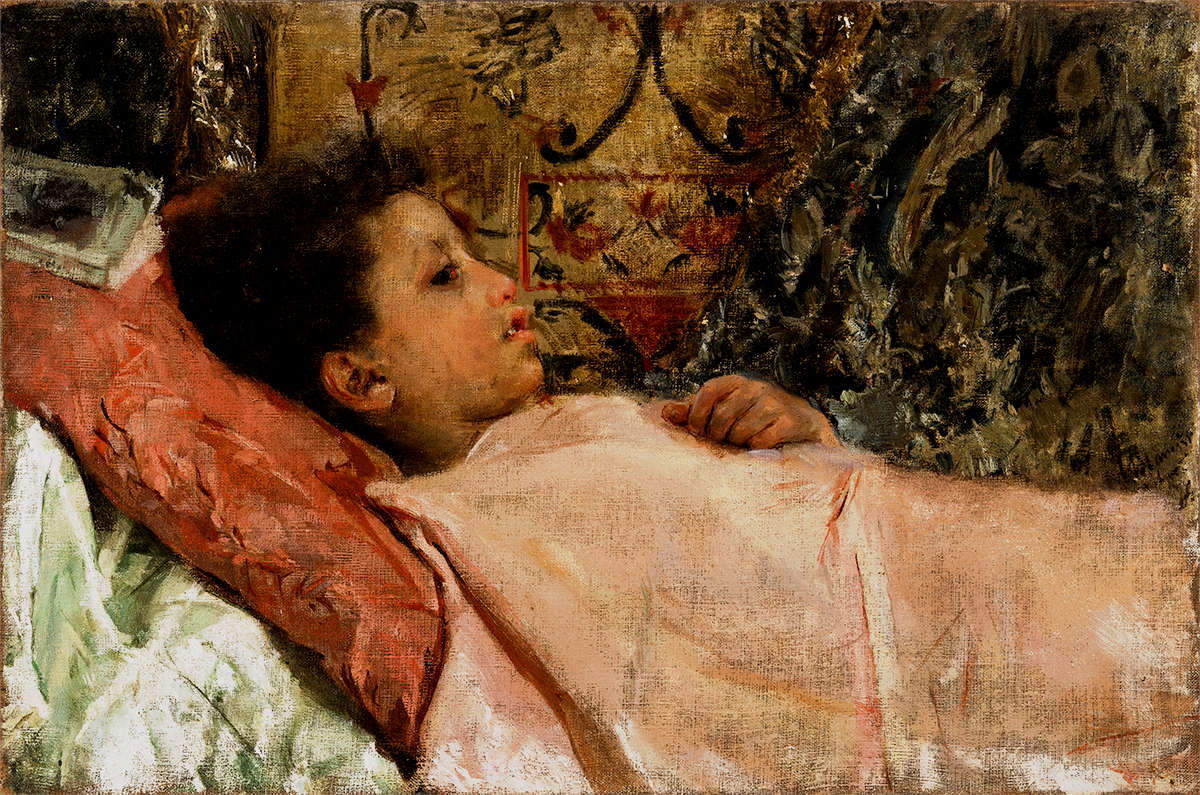

Southern School

Here the name of the Apulian Giuseppe De Nittis stands out, who in Paris approached French currents but maintained the strong figurative framing he had learned in Naples and which made him famous. It was precisely in Naples, alongside and after the school of Resina, that a group of strong artistic personalities of the second half of the nineteenth century started up, bearing the names of Francesco Paolo Michetti, the moving Antonio Mancini, Raffaele Ragione Attilio Pratella, Rubens Santoro, Vincenzo Irolli, Edoardo Dalbono and others. Their painting touches on the great outdoors, the sea, some urban interiors of character, as well as the most intense human situations, without forgetting Domenico Morelli, with his almost romantic desire, Filippo Palizzi, great verista, and Francesco Lojacono, trepid and wide-ranging landscape painter.

Also on the great Neapolitan school lies the precise analysis of Andrea Baboni, who knows how to distinguish with acumen the inspirations and compositional and chromatic translations of these proclaimers of the innumerable varieties offered to sight, feeling, and heart.

Veneto School

Northeastern Italy had a peculiar affair. In their time Giorgione, Cima and Giambellino made their poetics rest most sweetly on the soft hills of the terrestrial Venices, thus leaving room for landscape. A few concessions were also given by Titian, but the torrentiality of Tintoretto, the courtly language of Veronese and the seventeenth-century rumination covered those germs that finally resurfaced first in urban vedutismo and then in the freer vedutismo of the Guardi and their contemporaries. It took the “minor poets” of the Julian sea and enchantments to offer us a fascinating and prehensile anthology, itself absolutely enhanced by Baboni’s studies. We are faced with magnificent names, and we point them out with lively pleasure.

Poor and lagoon Venice is taken as a subject by the free painters of the maritime and Julian area, among whom stands out the strong and lyrical personality of Pietro Fragiacomo, also from a modest family but full of splendid pictorial enthusiasm, who succeeds in giving us beautiful visions of inland water lanches as well as of the marinas. He is joined by Guglielmo Ciardi with a painting of impetus, in broad strokes, but strongly constructed. Venetian painters very attentive to the life of the people and the facts of the popular calendar were also Luigi Nono and Giacomo Favretto who illustrated customs and events.

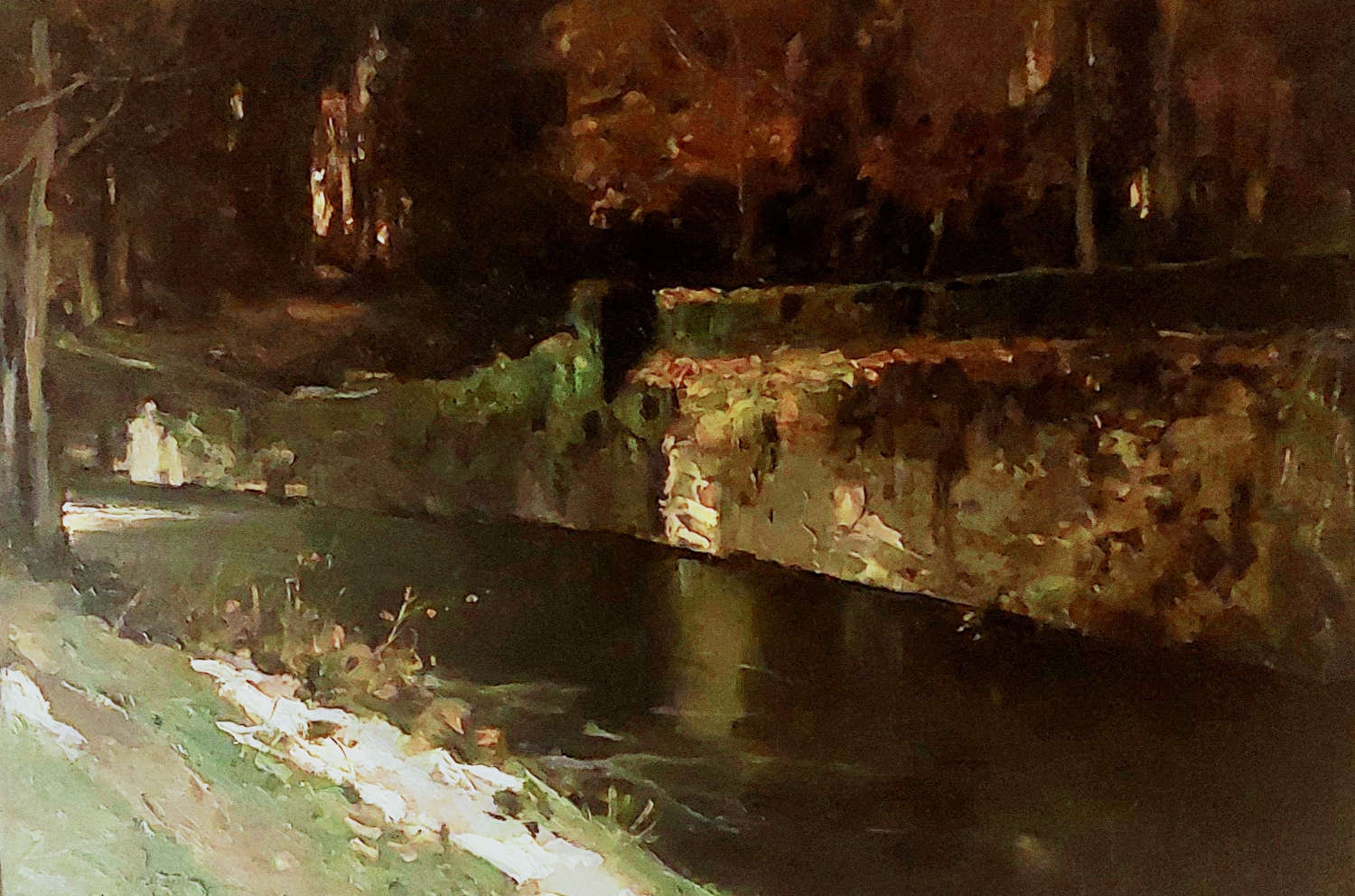

Piedmontese School

Among the best-known artists who held high the Piedmontese school of painting, which was very attentive to Europe, were the celebrated master Antonio Fontanesi (1818-1882), very rich in pathos; then Lorenzo Delleani, Vittorio Avondo, Matteo Olivero, Carlo Pittara and his flankers in the Rivara School, all of whom were in some way linked to Enrico Reycend (1855-1928), a very sensitive international painter. Intense attention to landscape was the application of a host of these and other young painters, born around mid-century, who were able to compare themselves more directly with the Barbizon School and the French Impressionists: Andrea Baboni gives a careful analysis. In the Savoy capital there was a wide interest especially in painting. For the sake of curiosity we will say that Delleani was among the founders of the Circolo degli Artisti di Torino, which exceeded seven hundred adherents and which also saw Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, as a member!

Delleani, Avondo and Olivero were imbued with an enveloping, often sighing naturalism, always strongly linked to the enchantments of the elements and the breaths of the soul. Later the sublime Divisionist works of Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo and Carlo Fornara would give a quivering dignity, above the times, to the Piedmontese school.

Emilian School

It remains difficult, conceptually and visually, to identify an Emilian School. The very nature of this vast area and the imprecise - we would like to say available and polyvalent - character of its population must make us prepared for solutions among them. The nineteenth-century Emilia is rich in many names that we could hardly call “minor,” scattered among a thousand dedications and among them some very straightforward ones of smug verismo, and others adventurous, sustained by theatrical practice and a taste for surprise. Nineteenth-century Emilia could have remained under the great poetic wing of Antonio Fontanesi, from Reggio Emilia, but the very temperament of the master did not keep him still for a routine profession; nor would Po Valley, agricultural practicality have sustained a lyrical naturalism as fragrant, intimate and totally engaging as his.

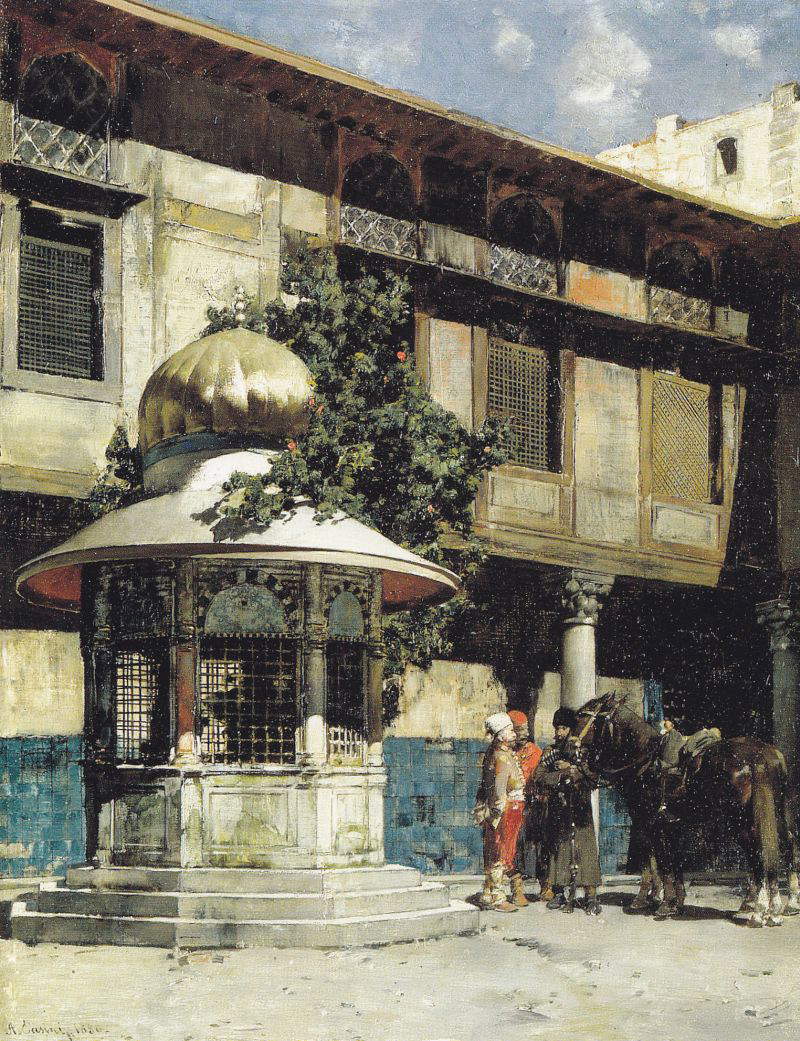

This has been carefully noted by Andrea Baboni in his extensive critical work. We thus meet three different artists: Gaetano Chierici, with a great performing hand, who repeatedly allowed himself to be attracted by the innermost scenes of peasant families, children, old men, and musicians; then the adventurous Parma-born Alberto Pasini, who was one of the first Italian orientalists and who brought here colors and scenes from the world “beyond the sea”; and as a third instead Stefano Bruzzi, from Piacenza, who truly painted nature in its most varied aspects, especially with snow, and with its most direct inhabitants, such as peasants, wagons, donkeys, and beautiful sheep.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.