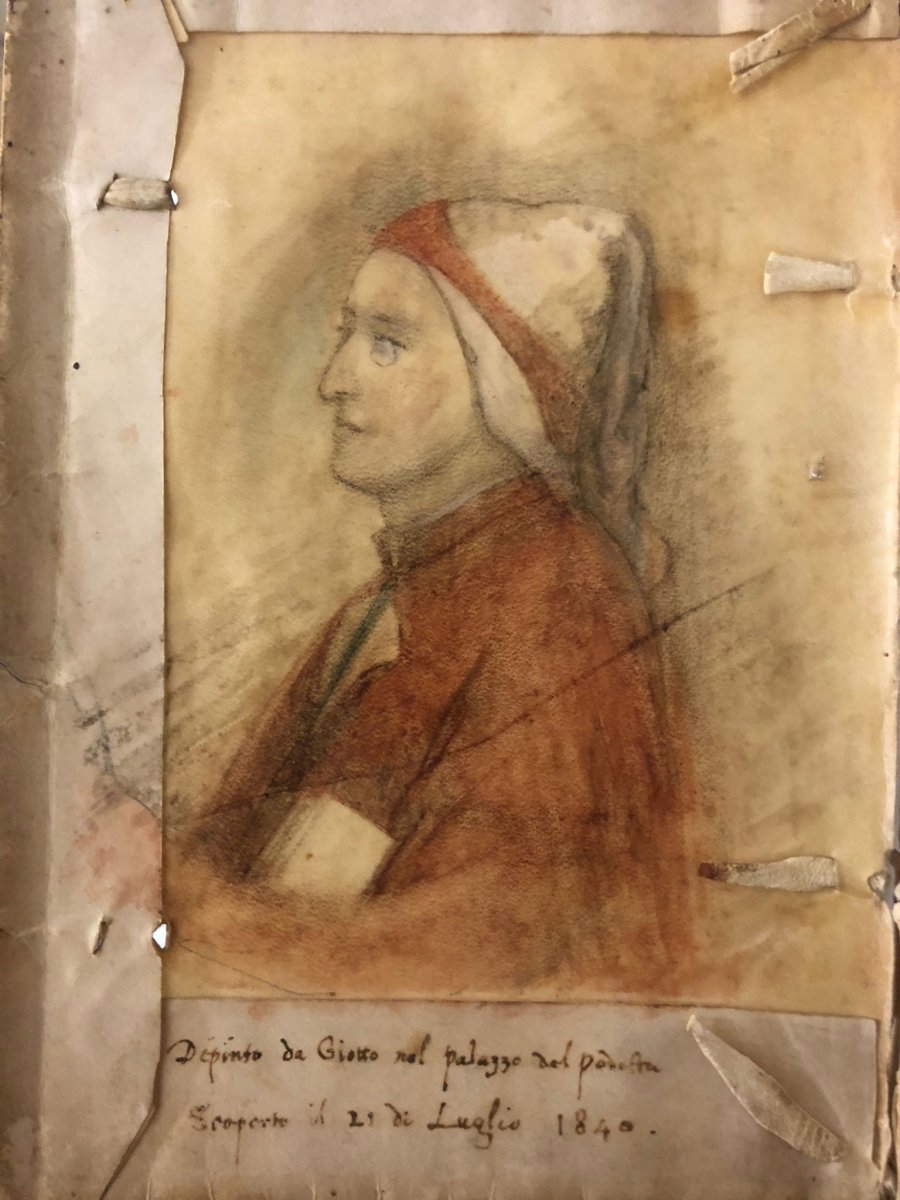

A portrait filled with "sensitivity, kindness, love, and a demeanor that breathes the spirit of the Vita Nova." These are the words that Mary Shelley, in 1844, used to comment on the fresco with the portrait of Dante Alighieri that had recently been found in the Chapel of the Podestà in the Palazzo del Bargello in Florence. At the time there was no doubt: the fresco found only a few years earlier, in 1840, was the work of Giotto. The critical debate on the frescoes in the Podestà chapel has continued for a long time, leading to the new, convinced affirmation of Giotto’s authorship of the work during the recent restoration, but what mattered at the time was the discovery of an entirely new Dante, of a portrait that was capable, Mary Shelley wrote, of “erasing all preconceived notions of the sullen severity of his physiognomy, which arose from the portraits that were made of him when he was advanced in years. Here we see Beatrice’s lover.” The discoverer of the portrait was an English artist, Seymour Stoker Kirkup, a Dante enthusiast, who involved the Piedmontese (but emigrated to England) Giovanni Aubrey Bezzi and the American poet Richard Henry Wilde in his undertaking: the three financed the essays for the removal of the paintwork from the chapel walls, carried out by restorer Antonio Marini and begun in 1839, and finally in July 1840 Dante’s portrait could emerge. Kirkup, Bezzi and Wilde later disputed the primacy of the idea, but it was unquestionably Kirkup who spread everywhere the image of the young Dante that Giotto had painted on the walls of the Bargello.

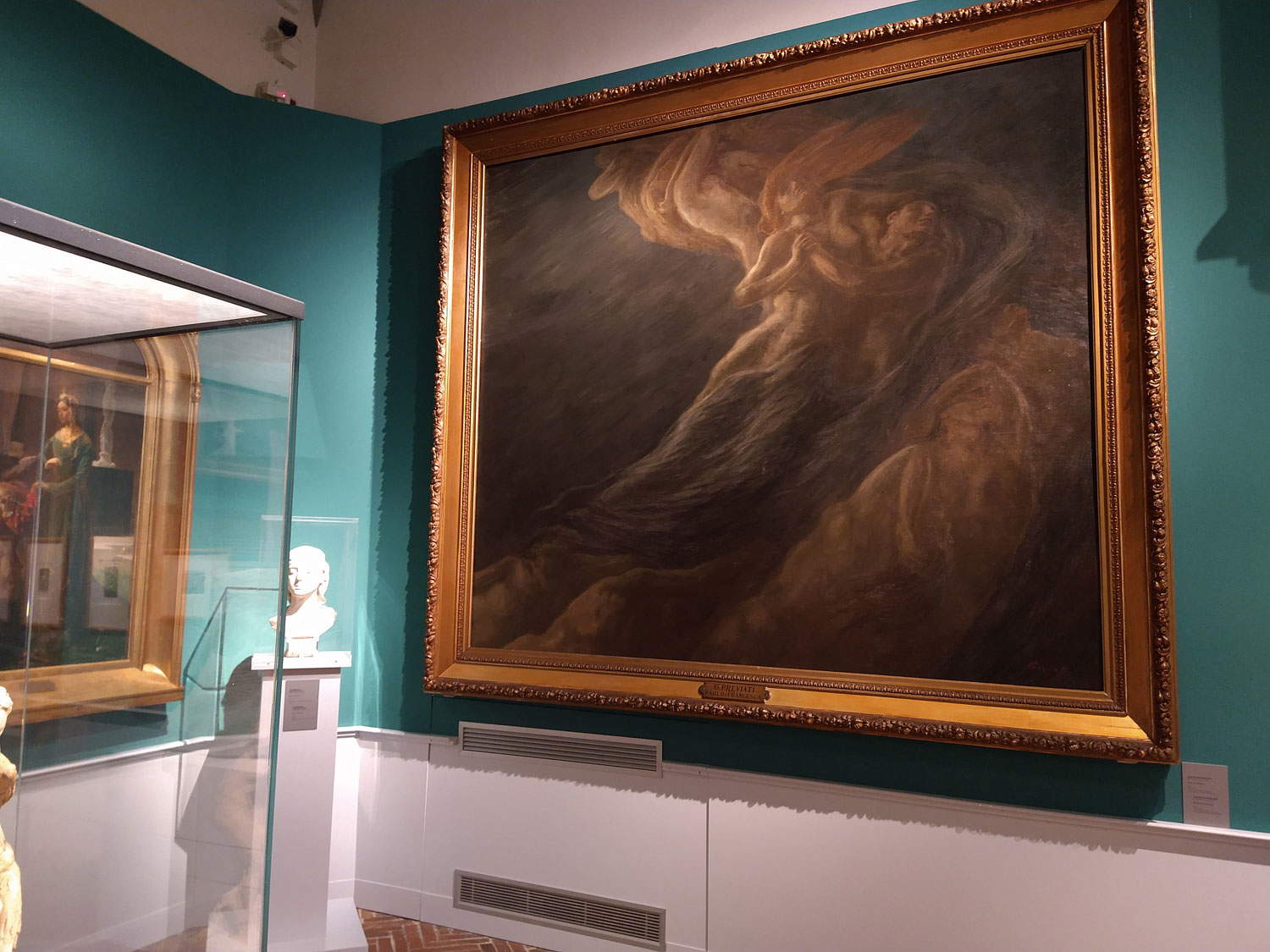

It was the beginning of a Dante sentiment that became far more pervasive throughout the continent. Of course, interest in Dante had already been reborn in the Romantic era: just think of William Blake’s visionary illustrations. But the possibility of giving a face to the Dante of the Vita Nova kindled the spirits and imaginations of artists and literati everywhere in Europe: it was as if a less rigid side of Dante’s character had been discovered for the first time. It is, in short, the beginning of a new story: the one told by the exhibition La mirabile visione. Dante and the Divine Comedy in the Symbolist Imaginary, curated by Carlo Sisi and Ilaria Ciseri, and underway at the Bargello Museum in Florence in the year of its seven hundredth anniversary: an exhibition that thus expands the story of the Podestà Chapel by a new chapter, because if with the summer exhibition Honorable and Ancient Citizen of Florence. The Bargello for Dante the attention was focused on the initial events of Giotto’s frescoes, the autumn exhibition sets the starting point in the nineteenth-century rediscovery, after centuries of oblivion, to then venture on an itinerary along almost one hundred years of Dante’s art. Two rooms, about fifty works: the layout suffers from this, almost like an antique picture gallery, but the exciting itinerary imagined by the two curators is consistent with the objective of the exhibition, which is to retrace some of the fundamental moments of Dante’s fortunes between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in order to offer the public an idea of the passions that the Supreme Poet had aroused in the artistic and literary circles of the time, especially in those most linked to the decadent aesthetic.

One of the triggering events of this fortune was precisely the discovery of Giotto’s portrait, which had widespread and numerous effects. The most immediate was the rise of new Dantesque impulses in that England that had first rediscovered Dante back in the eighteenth century, with Joshua Reynolds, in whom it is possible to identify a kind of father of today’s cult of the poet. Kirkup took care to share the discovery with his compatriots by sending across the Channel copies of the newly re-emerged portrait: this resulted in endless engravings, inspirations for new iconographies related to Dante’s life, interest in Dante’s entire production and in particular in his early works (before, on the contrary, attention was almost entirely captured by the Comedy). It was an “entirely new perception of the poet,” writes Ilaria Ciseri in the catalog, since it centered on a “young Dante, different from the more heroic formula of the laurel-crowned vate consolidated over the centuries.” A more human Dante in short, a Dante man of his time. A perception that spread to Italy as well.

The first of the exhibition’s six sections is devoted entirely to the new image of Dante: the opening is entrusted precisely to a drawing on parchment by Kirkup, preserved in the Bargello collections, reproducing Giotto’s Dante, which is flanked by further copies of the fresco in the Cappella del Podestà, and a canvas attributed to Gabriele Castagnola depicting Dante’s profile updated on the new discovery, but nonetheless still in line with the coruscating image of the poet popularized by the so-called “Torrigiani mask” (also on display in the exhibition), the image, which is difficult to date, believed to have been taken from Dante’s death mask (actually derived in all likelihood from a bust or at any rate a sculpture: the practice of carving funeral masks was not an early fourteenth-century custom). The second section, titled Incipit Vita Nova, examines the fortune of the image of the young Dante observed according to a precise inclination, that of the relationship between the poet and women, and capable of traversing various seasons of nineteenth-century art, including Symbolist visions, Pre-Raphaelite dreams, and Romantic afflatuses. Introducing the audience is a youthful painting by Raffaello Sorbi from 1863, from a private collection, which has as its theme the meeting of Dante and Beatrice: it is from the period when Sorbi was in the habit of frequenting historical subjects, partly declined according to the achievements of Tuscan naturalist painting of the time, and it deals with one of those subjects that, writes Carlo Sisi, “could meet the taste of foreigners attracted by the charm of a city where it was still possible to recompose, with the mediation of imaginative restorations or cordial artisan imitations, an unexpected and consonant harmony of art and life.” The Florence envisioned by foreigners is the one seen in one of the best-known Dante works of the time, Henry Holiday’sMeeting of Dante and Beatrice, among the most vivid witnesses of the enthusiasm for Dante that was spreading in England, and offered in the exhibition in an unpublished copy by Gustav Meisel (there are several unpublished works in the exhibition).

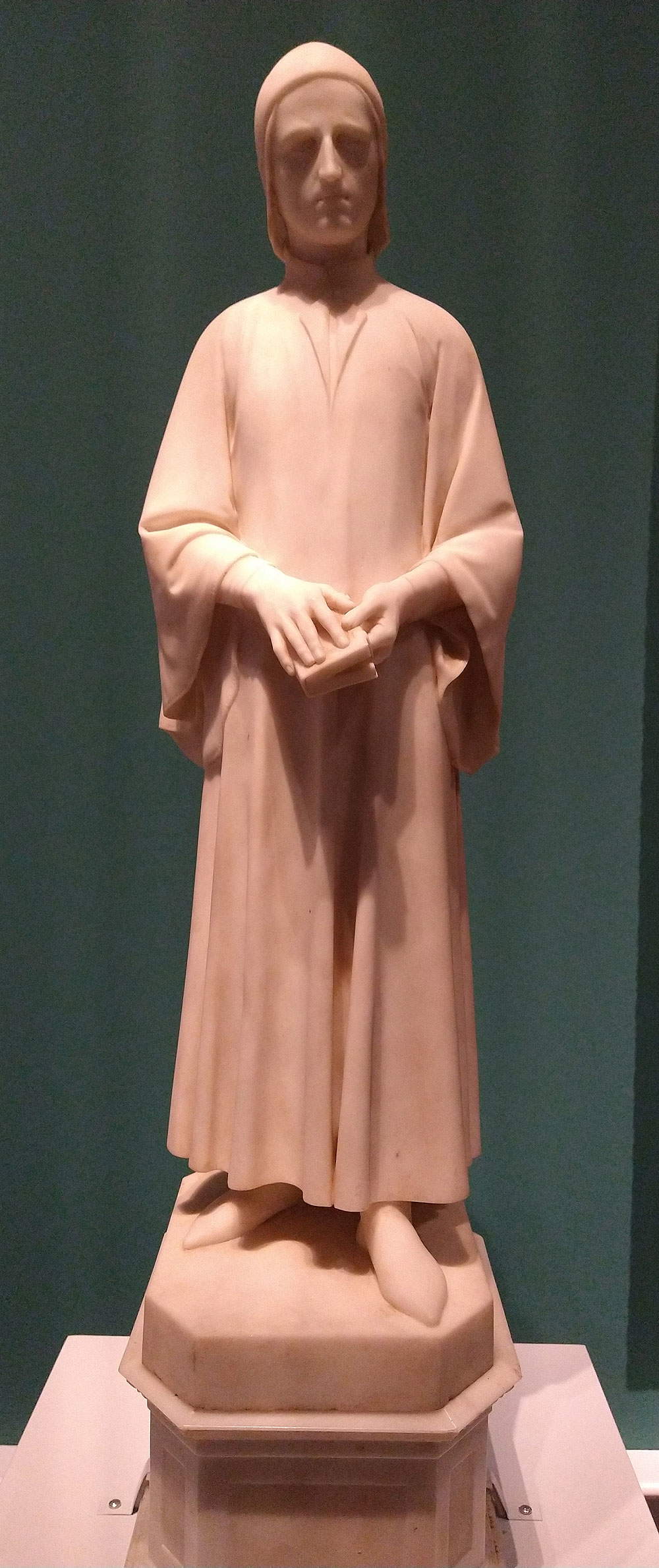

The Dante who inhabits these paintings is a proud and gentle poet, but he is also a man who is captured, with vivid realism, in the midst of his emotions: this is the same image that is conveyed by the two fine sculptures by Giovanni Duprè on display alongside, replicas (among many) of the Dante and Beatrice that were commissioned from him by Grand Duke Leopold II. They are works from the early 1940s and are among the earliest attestations of the iconographic fortunes of this “new” Dante, represented in the exhibition by several significant banners. Among the most observant are those of the Pre-Raphaelites and, more generally, of artists who dreamed of medieval atmospheres: here, then, is Dante Gabriele Rossetti’s Beata Beatrix, recalled in the exhibition by a copy of the Vita Nova with illustrations by Rossetti himself published by Roux and Viarengo in 1902, but perhaps even more eloquent is The Love of the Poet by a devout admirer of Dante such as Federico Faruffini, who with fervent participation, almost bordering on emotion, imagines the meeting between Sordello and Cunizza, with the lunette evoking, perhaps even more poignantly despite its size, the meeting between Sordello and Virgil in Canto VI of Purgatory. On the Symbolist front, in the first room of the Bargello here appears a “sudden and evanescent vision” (so Sisi) by Daniele Ranzoni that transfigures into a mysterious dream with emerald tones the image of Dante meeting a Beatrice who becomes an almost mystical presence. The same dreamlike accents are those on which Henri-Jean-Guillaume Martin, one of the first artists to join Sâr Péladan’s Salon de la Rose+Croix, intones his painting, on the same subject as Ranzoni’s, setting the encounter in a moonlit landscape where Beatrice, guiding Dante, shines with her own light. Finally, less spiritual, but also a luminous reverie image, is Giulio Aristide Sartorio’s Beatrice, which can be considered a conduit to the following section, devoted to the suggestions that Dante’sInferno exerted on naturalist and symbolist imagery.

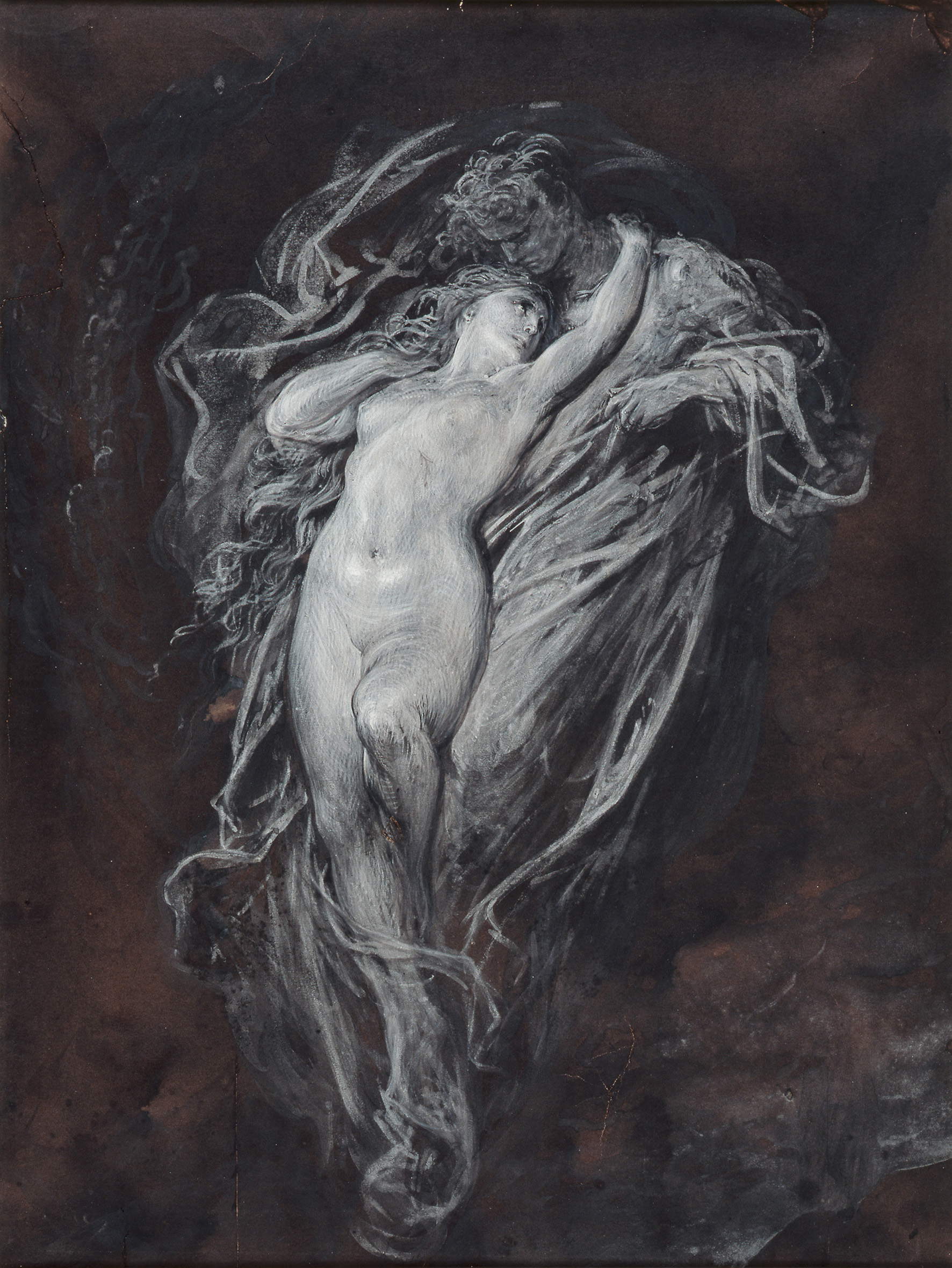

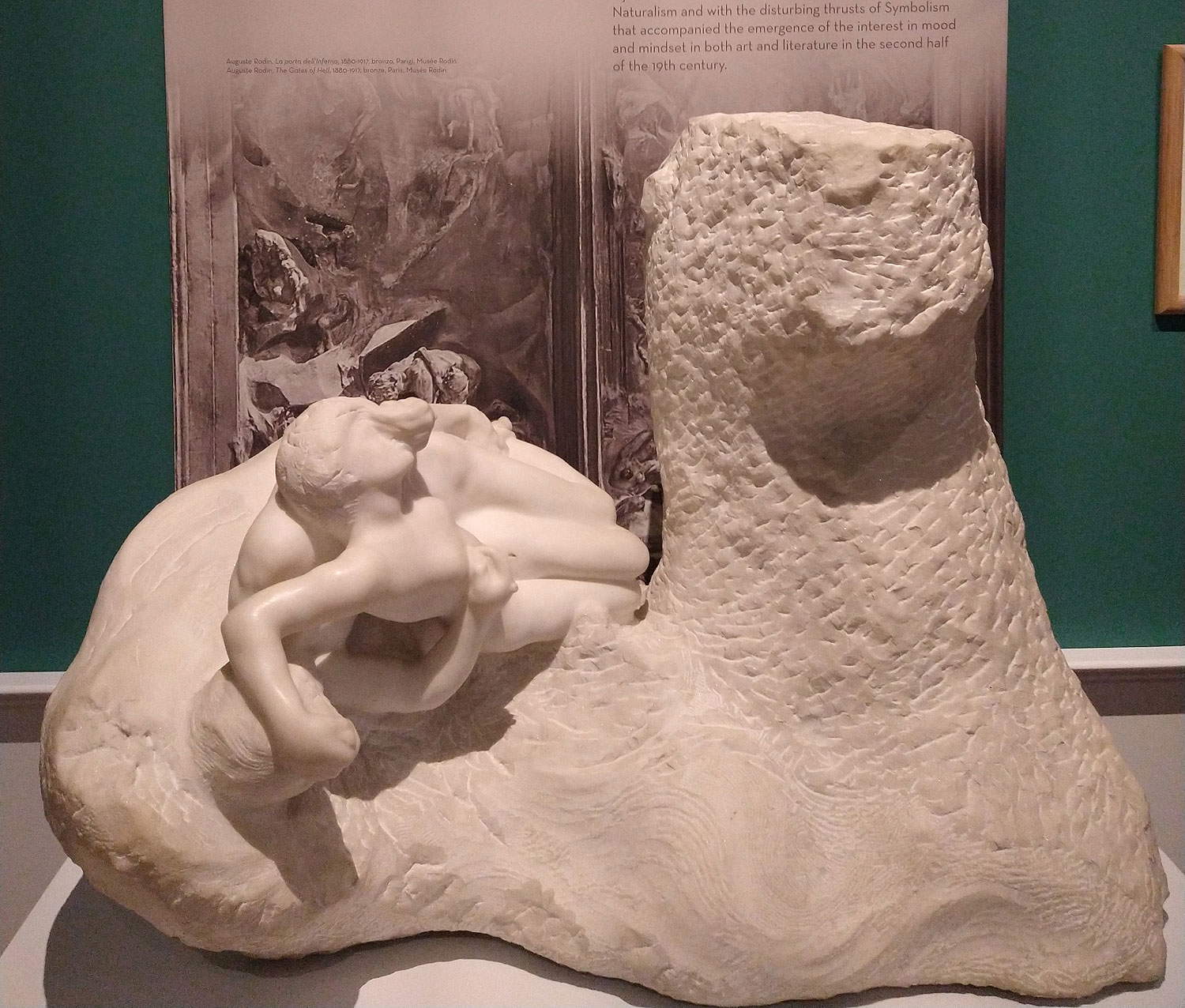

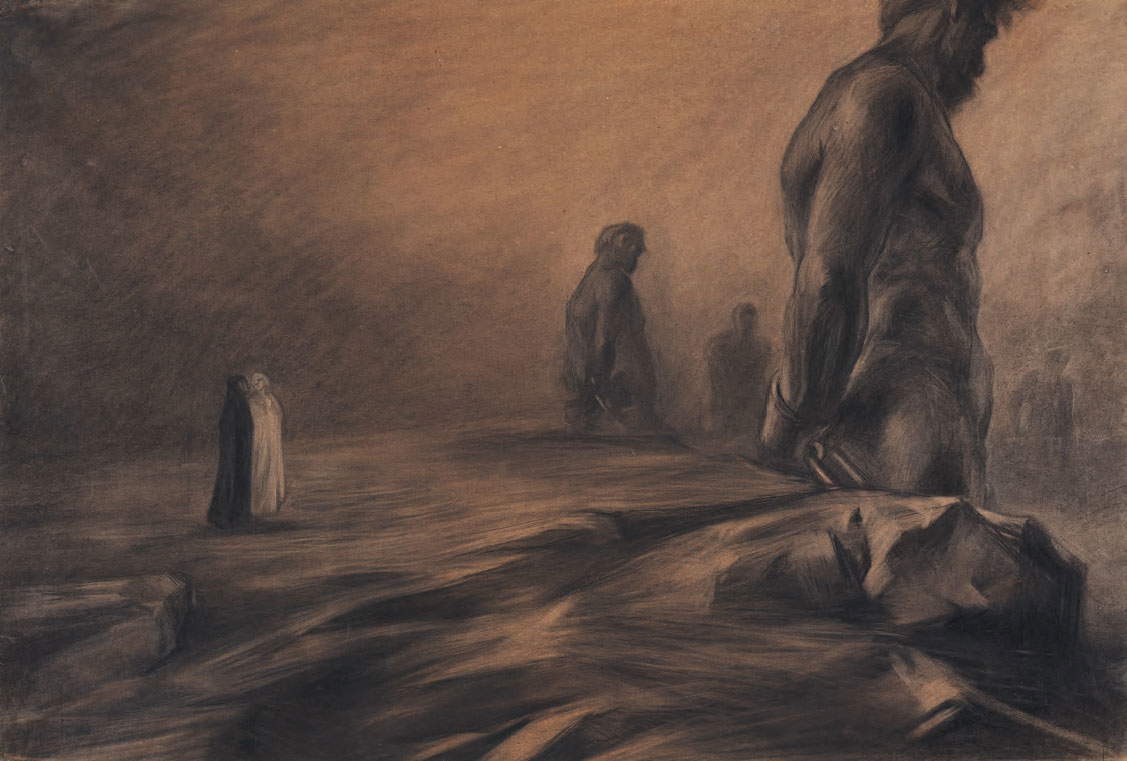

“For the Romantics and Decadents,” writes Silvio Balloni in the catalog, precisely framing the meaning of this chapter of the exhibition, "theInferno is life, because poetry and art embraced the dramatic nature of human experience, moving from an aesthetic vision, that of Neoclassicism, understood as abstract intellectual fiction disconnected from reality, toward a painting and sculpture that was content-oriented and open to the world, progressively extended, as the progress of the sciences and the individualism of consciences evolved, to encompass the whole spectrum of the True." Dante is, in other words, a poet who humanizes the Inferno by charging it with emotions, including love, that of Paolo and Francesca, evoked in the opening of the section by Gustave Doré, who, however, is not present with the well-known illustrations of the Comedy, but with a large paper arriving from the Musée d’Art Moderne in Strasbourg. For the decadent literati, Dante’sInferno is a kind of synthesis of the anxieties enveloping the real world: Leconte de Lisle, enthusiastically reviewing Baudelaire’s Fleurs du mal in 1861, found himself praising “the tortures of passion, the bitter sobs of despair, the irony and contempt” that mingle “with force and harmony” in the “Dantesque nightmare” that was the Parisian poet’s collection (who, by the way, knew Dante well). The bewitching force of Baudelaire’s verses could be approached by Auguste Rodin ’s marble that captures Paolo and Francesca light in the infernal whirlwind, just as Gaetano Previati does in that masterpiece that is the Paolo and Francesca of the Museo dell’Ottocento in Ferrara (unfortunately a bit sacrificed by the layout), clasped in a loving embrace that defies the gloom of that place that, of all places, is precisely the farthest from love. All the humanity of the best-known characters in Dante’sInferno also shines through in the pose of Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux’s Ugolino, gnawed by doubts and remorse as he ponders his atrocious fate, embraced by his young children.

The fourth section of the exhibition is dedicated to the illustrations of the Comedy and in particular to those resulting from the Alinari Competition, announced on May 9, 1900, by the famous photographic company, which aimed to involve the best artists in Italy in the creation of a sumptuous illustrated edition of Dante’s poem, which based its assumptions on the rediscovery of the symbolic values of the Comedy. Thirty-one artists took part in the challenge, including painters and draftsmen, who were required to send the judging committee two illustration proofs of as many cantos, as well as two endpapers and two endpapers. The proportions of the undertaking and the quality of the works that arrived at Alinari, not in line with what the commissioners expected, induced the firm to set aside the initial intention of entrusting everything to a single artist who had won the competition, and to open up, if anything, to a choral work, to which, moreover, Alinari itself also invited artists who did not take part in the contest. The winner was Alberto Zardo, followed on the podium by Armando Spadini, second, and Duilio Cambellotti, third. Better-known names today also took part in the competition: among others, Galileo Chini, Giorgio Kienerk, Adolfo De Carolis, Giovanni Costetti, and even a reluctant Giovanni Fattori, at the end of his career, who was initially disinclined to participate in the competition and later convinced by Anna Franchi. The Bargello exhibition displays many of the most interesting entries for this competition, which compose a sort of fascinating sampler of the trends in Italian art at the opening of the new century (especially since the works were all exhibited in one show): they range from Cambellotti’s powerful, mysterious and disturbing visions to the rawness of the older Fattori, from De Carolis’s realistic depictions to the torments of Alberto Martini, who participated out of the competition. Also on display are two illustrations by as many artists who were called ex post facto to participate in the Alinari venture: the sinuous Nymph Elice banished by Diana for Canto XXV of Purgatory, by Plinio Nomellini, and the moving St. Francis by Giuseppe Mentessi, for Canto XI of Paradise.

Also deserving of attention are the three etchings(The Meeting of Dante and Beatrice, The Death of Beatrice and Dante in his Cabinet) belonging to the series on the Vita Nova executed by the versatile Leghorn artist Alfredo Müller on behalf of the Parisian publisher Ambroise Vollard, an experience that was part of the climate of the French Dante revival of the time (Müller had moved to Paris) and that, writes Emanuele Bardazzi, "constitutes a different chapter, one that contrasts with the softer, more persuasive images, especially of women in contemporary and à la page attire, that [Müller] was going to engrave and that would establish him among the most significant and appreciated masters in the Belle �?poque of color etching and aquatinting."

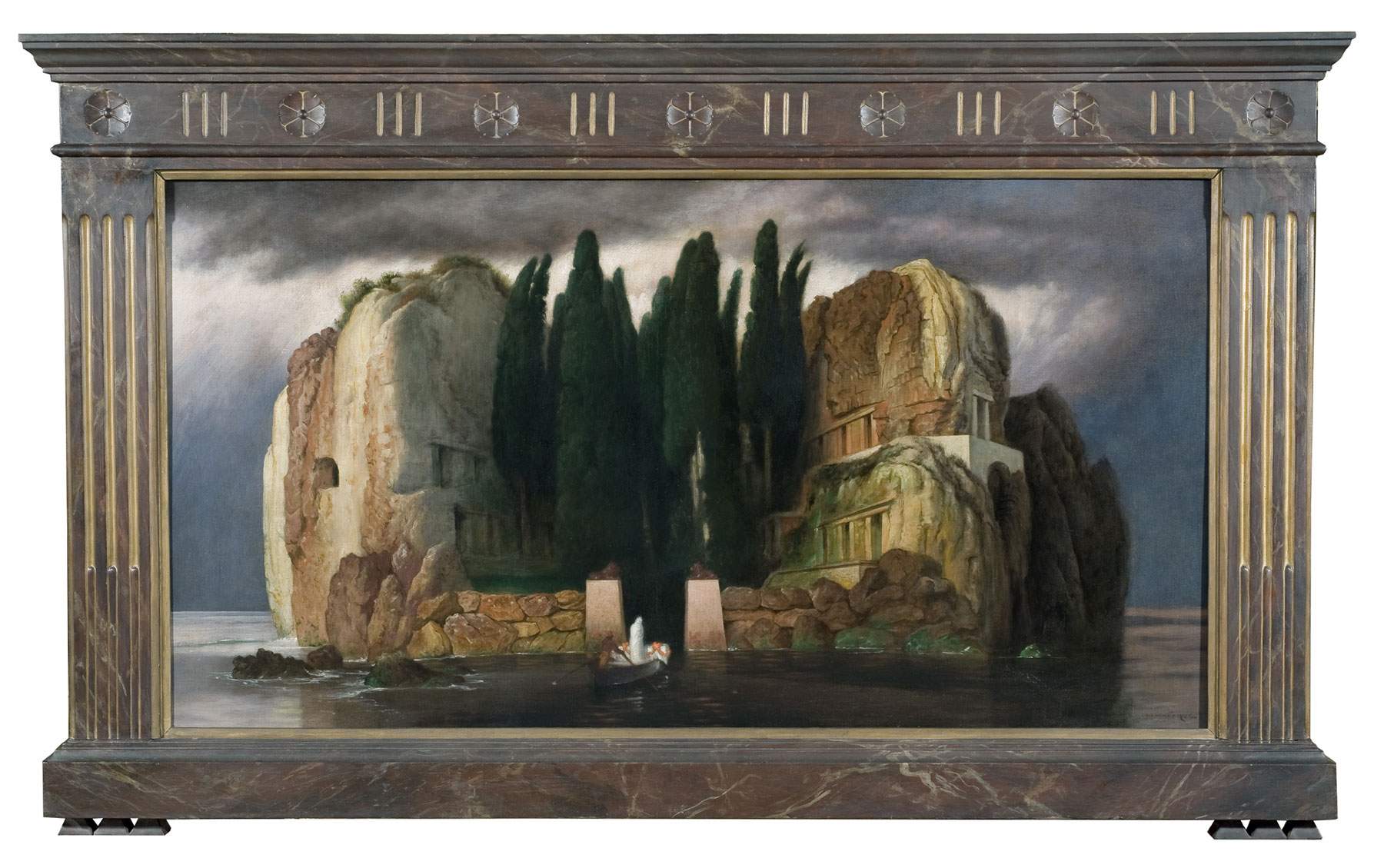

It continues with a brief literary digression on the long-distance clash between Giovanni Pascoli and Gabriele d’Annunzio over their readings of Dante: Pascoli (the title of the exhibition refers right to his essay La mirabile visione) believed himself to be the most sensitive interpreter of Dante’s word and resented his rival’s success as a commentator on Dante, having been thunderstruck by the great poet after rereading him, past the age of thirty-five, during a leisurely stay in Corfu. The exhibition displays a number of objects that reveal the bond that united Pascoli and d’Annunzio with Dante: editions of Gabriele d’Annunzio’s Francesca da Rimini, Pascoli’s essay Sotto il vemale, and the Commedia published by Olschki with an introduction by the Vate alternate in a showcase that leads the audience to the conclusion, delegated to a single painting, a copy of Böcklin’sIsle of the Dead executed by Otto Vermehren, placed at the close to return to where the dream was born, that is, to the Florence that inspired the Swiss painter’s vision of his island, a sort of fantastic translation of the hillock of the English Cemetery in Florence, with a ferryman approaching it, calling to mind the poem’s Charon.

If, therefore, the Dante who inspired patriotic and bellicose sentiments in the Risorgimento era is well known (think of Canto VI of Purgatory, just as an example, but think also of the Supreme Poet’s exile past), the Dante considered a kind of prophet of free and independent Italy, the Dante of the great post-unification monuments (starting with the one that can be admired in Santa Croce in Florence), perhaps not so much that more human and less heroic Dante, capable of pandering to a more modern sensibility, who moved the souls of Romantic, decadent, Symbolist artists and literati: and an exhibition investigating this aspect of the reception of Dante’s work could only start from the Bargello, since part of the credit is due to Giotto’s portrait of Dante and his rediscovery by Kirkup. It is obviously not a complete or exhaustive exhibition (in the section on theInferno, for example, the curators have focused only on the figures of Paolo and Francesca and Ugolino), since that is not its intent, but it is a small and valuable review, perhaps a bit too concise in its illustrative apparatus, but nevertheless refined and clear in the scanning of its path. What emerges is an intimate Dante: that proud but at the same time sensitive, gentle and full of love Dante who so fascinated Mary Shelley.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.