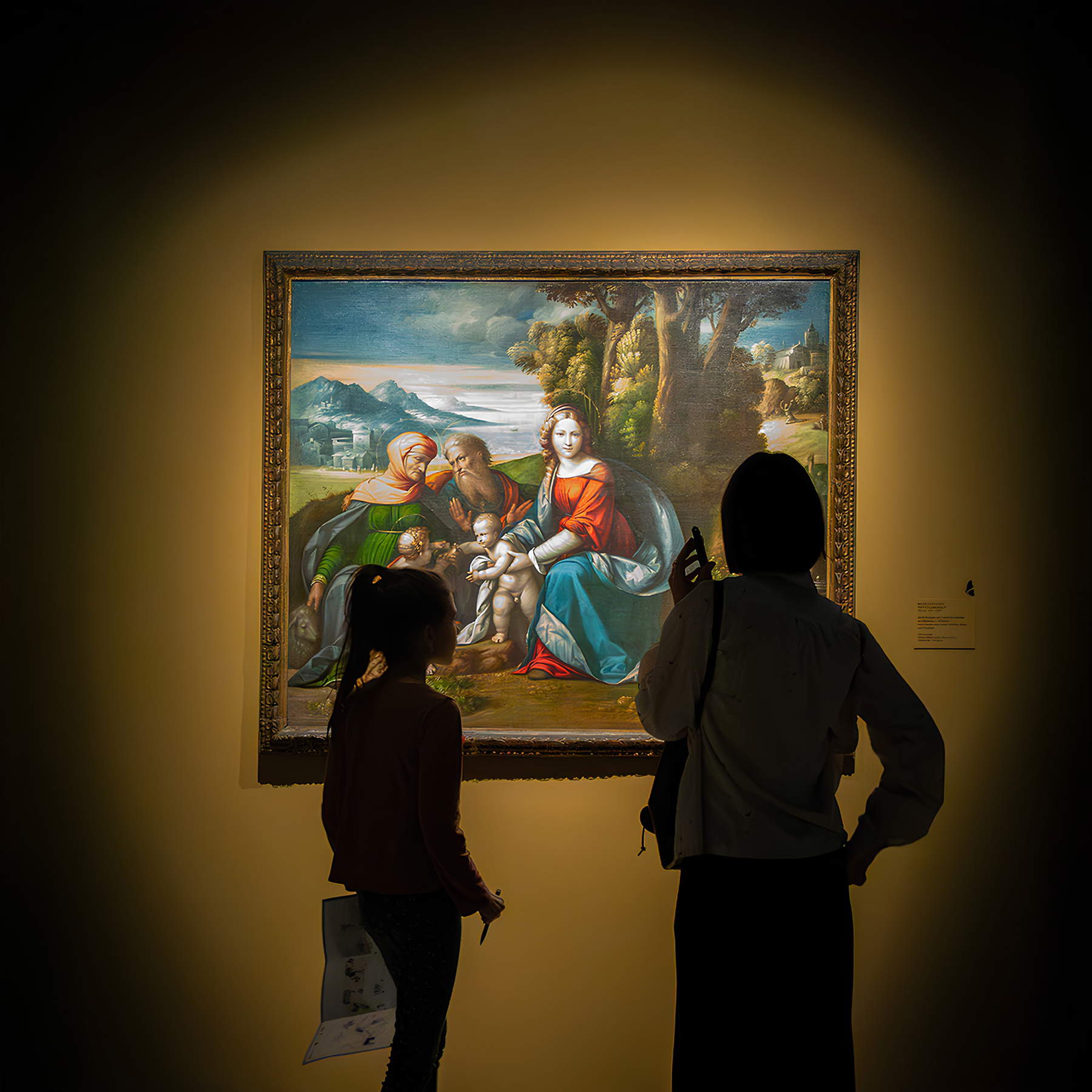

An intense journey among the great and forgotten of the 16th century in Ferrara. What the exhibition at the Palazzo dei Diamanti looks like

If we were to accompany Jacob Burckhardt on his visits to the galleries of Rome and listen to him as he pauses to describe the pieces that most and best captured his interest, we would most likely derive sharp adjectives from them, suitable for defining most of the artists uncovered inside the picture galleries. It also applies to all the four greats of early 16th-century Ferrara painting: here then Ludovico Mazzolino might be the “brilliant,” because his paintings, Burckhardt writes, “can be seen shining from afar in the galleries like precious stones.” Dosso is the “fiery,” the painter who “overwhelms Raphaelesque classicism with his chromatic moods and his often disjointed and overflowing forms.” Garofalo is the “elegant,” a balanced and measured painter “like a sixteenth-century Nazarene,” while Ortolano is the “frank,” the essential painter “always touched by a light of exciting intensity.” Burckhardt also added Girolamo da Carpi to the four, but he was of a younger generation, which is why he was not included in the exhibition that Palazzo dei Diamanti dedicates to the four brightest stars of the early 16th-century Ferrara firmament(Il Cinquecento a Ferrara. Mazzolino, Ortolano, Garofalo, Dosso), the second chapter of a tetralogy that began last year with the exhibition on Ercole de’ Roberti and Lorenzo Costa, ideally anticipated by the 2007 exhibition on Cosmè Tura and Francesco del Cossa, and which will continue, as has been announced, with the monograph devoted, precisely, to Girolamo da Carpi, and with the epilogue on Bastianino and Scarsellino. The lens of the two curators Vittorio Sgarbi and Michele Danieli is now focused on the first thirty years of the sixteenth century and on those four extraordinary artists, all born in the 1980s, children of a world that was changing with great rapidity, open to the most diverse experiences, heirs of a Ferrara that lost its three leaders, namely Tura, Cossa, and Roberti, when they were children or little moreThey were the heirs of a Ferrara that had lost its three masters, Tura, Cossa and Roberti, when they were children or little more, brilliant and intelligent renewers of a tradition that had been carried to the dawn of the sixteenth century by the devoted Domenico Panetti and Michele Coltellini, masters of most of these prodigious, imaginative, modern youngsters, capable of painting delicate poems, each with his own temperament, each with his own models, each developing his own language, defined, original. One does not get bored at Palazzo dei Diamanti, one does not run the slightest risk of being disappointed by this solid exhibition, well anchored to the pillars of its scientific project, capable of preserving intact the international scope of the chapter that preceded it.

Yet the names of the four protagonists are certainly not among the best known in art history. Perhaps only Dosso is surrounded by anallure comparable to that of the three masters (it should be noted, incidentally, that the exhibition completely banishes the form Dosso Dossi, which has now entered common usage but is the result of an eighteenth-century error). The others are little more than three unknowns. Ask even an insider if he has ever seen a work by Mazzolino (Garofalo may not have, for he was among the most prolific painters of his time, and his works can be found in museums throughout Italy): puzzled looks will be exchanged. On the Ortolano even more so. Why were these four artists, despite having made Ferrara shine in a varied and radiant light, almost forgotten? Some say it was the fault of the Devolution: when Ferrara came under the pope in 1598, their masterpieces that adorned the churches of the city and territory took their way to all corners of the Papal States. A despoliation that cannot be compared to those to which Napoleon forced Italy two centuries later, but that great damage was done to the artistic fabric of Ferrara. Then there are those who, like Mazzolino, had the opportunity to work mainly for private patrons: its rarity in public contexts has therefore not favored its knowledge. Yet these facts alone do not explain why the spotlights on Ferrara’s early sixteenth-century generation have been extinguished, do not explain why the manuals that also devote ample space to the three masters on the contrary ignore their sublime continuators, do not explain why their names tell the public little or nothing. Even of Tura, Cossa and Roberti there is not much left in Ferrara. The reasons then are varied.

On some of them, meanwhile, burdened prejudice. Take Benvenuto Tisi known as the Garofalo, perhaps the most studied along with Dosso, yet long considered a repetitive artist, a sort of anonymous provincial who at a certain point in his career was thunderstruck by Raphael and who for the rest of his life would continue to paint under the secure foliage of a composed and pleasing classicism. In reality, his experience was much more varied and multifaceted, and that same versatility was perhaps the most common feature of all four of them, but at the same time it was among the reasons that decreed their poor fortunes, and not only because in the past any form of eclecticism was looked upon with certain suspicion by critics: the dispersion of their works made their personalities more difficult to reconstruct, the sudden changes in their manners complicated scholars’ work in no small measure, and the scarcity of documents about them accomplished the rest. Dosso has been saved in part because of all of them he was the most true to himself despite the extravagances of his paintings, and Garofalo because he was an artist not only with a very long career and abundant production, but also because he used to time his works with a constancy that perhaps has no equal in the sixteenth century (Danieli recalls that there are more than forty works of his dated: there was probably no other artist at that time who was so meticulous in reporting the year of the works). Besides, their fortunes were also partly marked by the fact that the Ferrara of Mazzolino, Ortolano, Garofalo, and Dosso suffered, at least from a critical and art-historical point of view, the end of the polycentrism of the Second Renaissance, the end of that’balance (a balance that was not only political, but to some extent also cultural) that had been broken by the Italian wars and that had made Rome and Venice emerge, at those chronological heights, as the two poles toward which the interests, cultural and economic, of most of the artists of Italy converged. Including those from Ferrara: in 1512, Alfonso d’Este, on a diplomatic mission to Rome from Pope Julius II, brought some artists with him, who had the opportunity to climb the scaffolding of the Sistine Chapel before Michelangelo finished the work. Garofalo was impressed. And when one could not go directly to Rome, one nevertheless suffered its reflection: the arrival in Bologna of Raphael’sEcstasy of St. Cecilia , painted in Rome, convinced Garofalo and the Ortolano to convert to the word of a Raphaelism that was never, however, a pale imitation for them, as is easily seen in the exhibition. Lastly, Ferrara’s total extraneousness to the events that followed the diaspora of artists after the Sack of Rome should be noted: none of the artists who left Urbe came to bring Roman novelties to Ferrara’s soil. Novelties that would be grasped, later, to a certain extent by the anonymous Master of the Twelve Apostles and then, much more convincingly, by Girolamo da Carpi, called to Ferrara by Ercole II d’Este, successor to that Alfonso who had died in 1534 after holding power for thirty years. And 1534 is also the date that closes the chronological horizon of the exhibition.

As was the case for its sister exhibition last year, this second chapter of the Renaissance in Ferrara is conceived as a compelling journey through time that takes its starting point in the context, and thus begins in a Ferrara that had been deprived of outstanding personalities: at the end of the fifteenth century Ferrara painting, with no more Cosmè Tura, no more Francesco del Cossa, no more Ercole de’ Roberti, and with Lorenzo Costa who had been called back home from nearby Bologna just to measure himself against thefeat of the fresco decoration of the apse of the Cathedral, could no longer count on the brio of the three great masters and had taken refuge in the compassed ways of Domenico Panetti, to whom the role of dominator of the city scene fell for a few years. His is the Madonna and Child from the Grimaldi Fava Collection, among his few paintings on display (but to see more of Panetti’s work, simply go up one floor and visit the Pinacoteca Nazionale, in the other wing of the Palazzo dei Diamanti), a work that reveals an interest in Lorenzo Costa but also in theanother Ferrarese of his age, Boccaccio Boccaccino, who among the artists active in Ferrara at the end of the century is to be considered the most original, especially by virtue of his early interest in Leonardo’s innovations mixed with what he had learned at home. On display here is his Adoration of the Shepherds, on loan from the National Museum of Capodimonte, a work of solid Robertsian implantation, as can be seen by looking at the hut, but with eyes also turned toward the Milan of Leonardo and the Leonardoesque. Boccaccino was a wandering painter, however, who had already traveled extensively as a young man, and who was then forced to leave Ferrara for good in the year 1500 for having murdered his wife “ch’el trovò farli le corna et g’el confessò” (so in a chronicle of the time reported in the nineteenth century by Giuseppe Campori).

It is especially between Panetti and Boccaccino that the beginnings of Ludovico Mazzolino and Benvenuto Tisi known as Garofalo, the first two artists of the Ferrara tetrarchy to be encountered along the exhibition itinerary, move, compared with the elusive Reggio Emilia artist Lazzaro Grimaldi: His is the dreamy 1504 altarpiece from a private collection, a rare opportunity to see an artist even more scarcely considered by critics than the exhibition’s protagonists, yet capable of whimsical finesse that perhaps did not fail toexert a certain fascination on those two young men who, at that very end of the 15th century, could see him at work (along with Lorenzo Costa, along with Boccaccio Boccaccino, along with the Tuscan Niccolò Pisano) on the building site of the apse of the Cathedral, the main artistic endeavor of that era: Grimaldi is an artist who transfigures the extravagances of Ercole de’ Roberti a suspended, dreamlike atmosphere, some reflection of which can perhaps be felt in the youthful Adoration of the Magi by Mazzolino on display next to him, a loan from France and an essay in the experimentalism that must have characterized his genius even at a very young age (he was 20 at the time). Less exuberant, on the other hand, is Garofalo, who in his Madonna and Child , “extremely youthful” (so Danieli) still bears the memory of the teachings of the master Panetti (Vasari already reported the news of his alumnus at the older elder fellow-citizen), touching, however, as can be detected by lingering on the gazes of Mary and the infant Jesus, an emotional intensity that was unknown to his mentor and that reveals his interest in Boccaccino’s painting. The reference to Lorenzo Costa, on the other hand, seems to bring to life theAnnunciation from the Cini Gallery that occupies the center of the room, and the same is true of Giovanni Battista Benvenuti, known as l’Ortolano perhaps because of his father’s profession, who is encountered as one is about to leave the room and who, with theAdoration of the Child with Saint John the Baptist, a “tiny gem” as Davide Trevisani defines it in the catalog, attentive and devout, simple and fine, provides the visitor with an icastic example of the beginnings of a painter as welcome in his time as he is uncertain today. Of the four, he is the one about whom news is most scanty, but according to the most up-to-date reconstructions he is an artist whose tooling appears characteristic from the outset, for an artist who, Trevisani again writes, “has something of the plasticatore and of ’lombardo’ of Bramante’s ascendancy in him, so much so that the enameled and cut rendering of the material evokes his taste.”

This “enameled and sharp rendering” is not so much felt in the Circumcision encountered in the next room, an unpublished painting that appears as a sort of melting pot of references to which Ortolano might have turned at the beginnings of his career, and which is compared with a small, delicate, precious Giorgionesque pearl by Garofalo(Saint Luke portraying the Madonna and Child) and with Ludovico Mazzolino’s Nativity equally ready to listen to the Venetian echo, as much as, if anything, in Baura’s Lamentation , which figures as one of Giovanni Battista Benvenuti’s main masterpieces. In the exhibition it might seem to be a kind of hapax because there are no other comparable paintings, but in fact there are other peaks in his production (such as the Lamentation of the Borghese Gallery or the later St. Sebastian of the National Gallery in London, unfortunately not in the exhibition but reproduced in the catalog) of this astonishing classicism made of strong chiaroscuro, metallic folds, sculptural profiles, which condenses the fascination with Ercole de’ Roberti by implanting it on patterns and delicacies inferred from the great Bolognese Francesco Francia and opening it to modernity (and perhaps it is precisely Baura’s Lamentation that is dense with a modernity that not even in the works absent from the exhibition touches comparable heights). In parallel, the review has us follow a Garofalo who follows in his lovable variations on Giorgione (the Madonna and Child with Saints Sebastian and Margaret of Antioch) and a Mazzolino who, on the contrary, prefers to look elsewhere. At this point the review dedicates a lunge to him to prove his bizarre autonomy (“restless and eccentric talent” Silla Zamboni had defined him, in the first monograph ever written on the painter): the reference to an Ercole de’ Roberti is an inescapable fact for him as well, but his production refuses to frame the legacy of his ideal master within the meshes of a sober classicism. If anything, Roberti’s extravagances lead him to look sometimes toward the stranger artists of Renaissance Emilia (Amico Aspertini, on display with a Saint Christopher), sometimes toward the north, toward Dürer. One cannot otherwise explain a cornerstone of his production such as the Sacra Famiglia of the Lia Museum in La Spezia, a signed work in which Ludovico Mazzolino’s narrative ease is at its best, a signed work in which there is no shortage of wacky inserts (the monkey, an obvious Dürerian quotation, or the battle that decorates the relief resting on the arch brackets: elements, moreover, also present in his other paintings, so much so that the exhibition also features battle scenes by Ercole de’ Roberti and Amico Aspertini to make explicit the models Mazzolino had in mind), just as it is difficult to explain two other masterpieces of Nordic taste, namely the Circumcision of the Cini Gallery and especially theAdoration of the Magi of the Magnani-Rocca Foundation, the pinnacle of a fantasist who among the objects brought by the Magi also puts one of those splendid pastille caskets that were typical of Ferrara production of the time (Palazzo dei Diamanti dedicated a few months ago a small, tasty exhibition to this singular production as well).

Continuing on, from the Gemäldegalerie in Dresden comes a staple of Garofalo’s career, the Minerva and Neptune , which subtends an allegory of Alfonso I d’Este, depicted in the guise of the god of the sea, indicated as victorious by the goddess of wisdom: the duke probably wished thus to celebrate Ferrara’s victory in the naval battle of Polesella in 1509, an important episode in the war of the League of Cambrai during which the Ferrarese fleet had succeeded in soundly defeating the Venetian fleet, which sank almost entirely in the Po delta. It is Garofalo’s earliest known dated work, and more importantly, it is Garofalo’s first response with respect to his trip to Rome where he got to meet Michelangelo and Raphael, complete with a probable quotation, albeit reworked, of the gesture from the Sistine Chapel’s Creation of Adam : but beyond this detail, notes Michele Danieli, “the turning point with respect to the previous production is undeniable, starting above all with the setting: never before had Garofalo measured himself with such a calm, symmetrical and solemn rhythm, with a group of such monumentality, and his achievement shows the uncertainty of the beginner.” A breakthrough that also becomes a discovery in the Argenta altarpiece, displayed next to the Minerva and Neptune, Benvenuto Tisi’s first known ecclesiastical commission, and the first work he painted after meeting Raphael. Ortolano also knows a turning point, and even in his case the impetus is imparted by the vision of Raphael’s works (to be read in this sense is the Holy Family in the Pallavicini Gallery), but according to Michele Danieli awork such as Christ Supported by Nicodemus, a late work by the Ferrara artist, denotes a certain interest in Dosso’s painting, to be read especially in the “psychological depth” that Ortolanus infuses his figures with. Dosso, the youngest of the four early 16th-century Ferrarese, enters the scene at this point, anticipated by the John the Baptist from the Palazzo Pitti and the amusing San Girolamo (amusing because of the way Dosso signs himself: a D and a bone on the lower edge of the painting) displayed in the previous room.

Of the four, Dosso, a witch painter, is the most magical, most surreal artist, most interested in myth and literature, most inclined to be subjugated by the poetry of Giorgione but at the same time open to the ancient epic of Mantegna, the grace of Correggio, the country delicacy of Lorenzo Costa. And he is a painter at ease with a wide range of genres: from myth (the Nymph and the Satyr, the Giorgionesque debut of his activity) to portraits (that of Niccolò Leoniceno or the even more intense one of an old man in fur coat traditionally identified as Antonio Costabili, the patron of the sumptuous polyptych that Dosso painted together with Garofalo and that s’admired at the Pinacoteca Nazionale, to be considered, it is worth reiterating, an in situ extension of the exhibition), passing through the genre scene (the very special Zuffa at Palazzo Cini). Again, the room also presents Dosso as one of Alfonso I’s favorite painters: evidence of this is the Young Man with Basket of Flowers from the Longhi Foundation, formerly part of the decoration of one of the rooms in the duke’s apartment at the Castello Estense. A work that, writes Vasilij Gusella, stands out for its “great realism” in the “physiognomic characterization of the face” and for the "’preseicentesco’ character of the still life piece that aroused Longhi’s admiration in the pages of his Officina." Qualities that Dosso would maintain very high even in the continuation of his career.

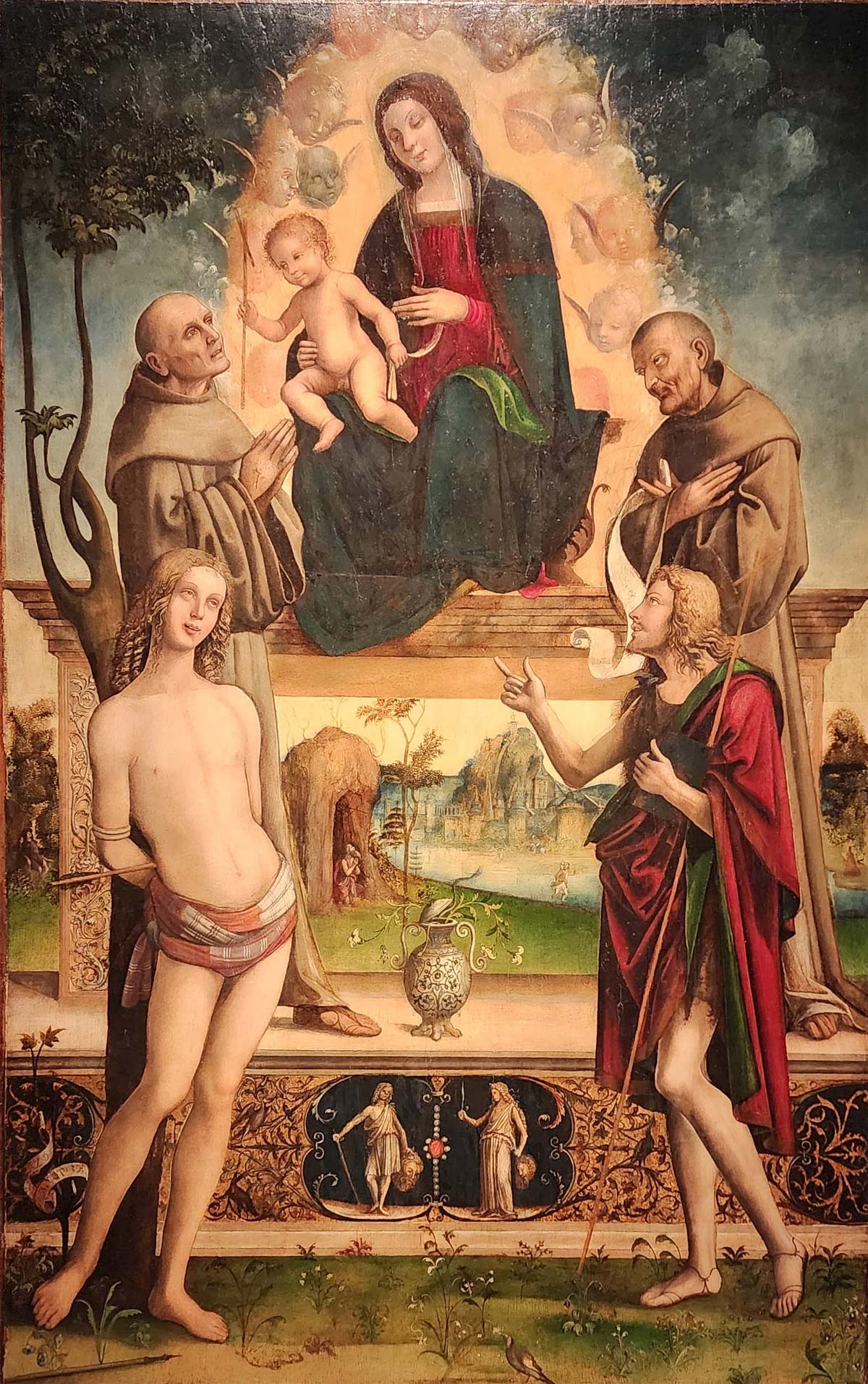

The following room is perhaps the most spectacular of the exhibition since it gathers a conspicuous number of altarpieces, to show the audience of Palazzo dei Diamanti how Mazzolino, Garofalo and Dosso (the Ortolano is missing from the roll call) had to try their hand at this genre. Garofalo, in particular, was of the four the painter who received the most ecclesiastical commissions: admirable is the Raphaelesque calmness, simple and immediate, of the Crespino altarpiece, especially when compared with Mazzolino’s Cremona altarpiece, a late work that in the throne seems almost to open itself up to a sort of Cossesque revival , but which because of its closeness to Dosso (especially in the way Mazzolino rendered the saints’ robes) has often been likened to the painter of Trentino origin, although the physiognomy of the faces leaves little doubt as to the name of its true author. It is, however, a work that Valentina Lapierre calls “enigmatic” since little is known about it (we do not even know where it was originally placed), and “anomalous” precisely because of this unusual proximity to Dosso, who is present in the room with the powerful and monumental St. Sebastian altarpiece. L’Ortolano returns in the next room, the one with which the Palazzo dei Diamanti exhibition bids farewell to him, who of the four is the one who died first, in 1525: in the last, Giovanni Battista Benvenuti is a painter who deepens established formulas, sometimes with some return to the past, more often with the refinement ofa manner that looks to Raphael, as in the Saint John the Baptist on loan from the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, or as in theAdoration of the Magi at the Magnani-Rocca Foundation, which does not conceal a continuing fascination with antiquities, and even the reception of some of Mazzolino’s cues. The exhibition also salutes him, who passed away in 1528, in a room that compares him with the Garofalo of the 1920s, to show how to the latter’s composed order (an example the seraphic Christ Carrying the Cross), Mazzolino responds with a disorder made up of crowded compositions (such as that of the violent Massacre of the Innocents) and meditations already imbued with mannerist, unreal and charged atmospheres (the Noli me tangere, Christ before Pilate).

Dosso takes a lone starring role in the following room, all dedicated to his masterpieces, to the works of the 1920s affected by “a classicist turn and a progressive adherence to the Roman manner” (so Marialucia Menegatti), to the more fairy-like products of his hand: not to be missed is the opportunity to see up close, in a perfect light, the Jupiter butterfly painter loaned from Wawel Castle in Poland, a work with a long and troubled history and a meaning that still remains obscure, probably to be read by focusing on the interests of Alfonso I. Parading through are the finest fruits of Dosso’s 1920s palette: the monumental, restless and beautiful Apollo from the Galleria Borghese, the dismayed Psyche from the Quadreria di Palazzo Magnani in Bologna, and then the excitement of the Jupiter and Semele, the country fable of Circe that arrived from the National Gallery in Washington, with those unmistakable late Gothic nostalgia animals. Closing the exhibition itinerary, the vicissitudes of the arts in Ferrara in the last years of the duchy of Alfonso I, before his death and the consequent handover to the new duke Ercole II (portrayed, moreover, allusively by Dosso in the form of a giant in the midst of pygmies in one of the last paintings on the tour itinerary): In the general climate of updated and restless classicism that pervades Emilian culture, evidenced in the exhibition by the presence of the terracotta busts by Alfonso Lombardi, the now 50-year-old Garofalo retains his Raphaelesque stance, as s’appreciates in the Madonna and Child with Saints in the Pinacoteca Capitolina mindful of the Urbinate’s Foligno altarpiece, while observing the innovations that Giulio Romano brought with him from the Eternal City. The Dispute of Jesus in the Temple is perhaps the painting where this slight shift is best grasped: the setting cannot fail to call to mind the School of Athens in the Vatican Rooms, but the central presence of the twisted column seems, rather than a quotation from the Healing of the Cripple, to be an insert motivated not only by the need to emphasize the presence of Jesus, but also by the desire to break the balances, albeit in a somewhat restrained manner. However, the new painting, the art of Ferrara at the dawn of the duchy of Hercules II, is closer to that of the Master of the Twelve Apostles, whose works close the exhibition: an unpredictable, versatile artist who, in the mid-1930s, Pietro Di Natale observes, “enriched with suggestions derived from Mazzolino, Battista Dossi and Girolamo da Carpi the education matured on the models of Garofalo,” an artist who in these years, as seen in the whimsical Adoration of the Magi, matured an eccentric and affected taste adapting to the trends of the time.

It will start from here, it is to be expected, the third chapter in the series that began with Renaissance in Ferrara, a project that, as was the case with last year’s exhibition, offers visitors to the Palazzo dei Diamanti another reconstruction of the highest level, a’deep and absorbing immersion among the vicissitudes of four protagonists of the culture of their time, who re-emerge from this focus with solid confirmations, relevant novelties, and pointed reconstructions where critics had long set aside their cares (the thought runs, of course, to the figures of Mazzolino and Ortolano, who emerge from the Palazzo dei Diamanti exhibition with updated redefinitions of their physiognomies). For the steadfastness of its scientific structure, for the quality of its installations, for the completeness of its selection, for the supreme value of its loans and for the intelligent and exciting construction of the exhibition itinerary, The Sixteenth Century in Ferrara. Mazzolino, Ortolano, Garofalo, Dosso can undoubtedly be considered one of the best exhibitions of the year. Therefore, the public interested in the vicissitudes of Renaissance art should not miss the opportunity to visit a vintage exhibition, it would be said, with positive meaning, as it is increasingly rare to encounter exhibitions built with the will to shed light on a particular historical period without pandering to fashionable tastes, organized with lofty but millimeter-accurate deployment of international loans, thus without unnecessarily displacing works that would add nothing to the discourse, and accompanied by a catalog useful for study and producing novelty.

In the catalog, Vittorio Sgarbi’s introductory essay is flanked by Michele Danieli’s chronological reconstruction of the vicissitudes of the arts in Ferrara from the year of Ercole de’ Roberti (1496) to that of Alfonso I (1534), and then David Lucidi’s contribution on a theme that is only touched upon by the exhibition (i.e., sculpture in Ferrara in the period examined), and an in-depth study by Roberto Cara on artistic commissions around Alfonso d’Este. This is followed by brief reconnaissance on the four protagonists, with Valentina Lapierre dealing with Mazzolino, Davide Trevisani with Ortolano, Michele Danieli with Garofalo, and Marialucia Menegatti with Dosso. Finally, two dutiful notes: first, on the itinerary to discover what remains in the city that the curators propose just before the exit: to be photographed with your smartphone to have it with you during the walk through the historic center. The second, on the philological musical accompaniment that gladdens visitors to the Palazzo dei Diamanti: since Renaissance Ferrara was one of the main musical centers of Europe, the curators thought it would be interesting to offer the public the suggestion of the music that was composed and played at the Este court in the late 15th and early 16th centuries: we have enough material to accurately reconstruct what Alfonso d’Este and his artists could hear at festivals, during religious celebrations, and in the streets when they crossed paths with wandering musicians. In the rooms, therefore, contemporary performances of the music of Ferrara at the time can be heard: there are panels offering insights into the subject and also playlists of what the speakers are playing. It is a symptom of supreme attention to the audience and of commitment that advances even beyond what is due. Shazam in hand, then, to also take home the musical memory of a memorable exhibition.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.