More than fifty years have passed since Dario Durbè could still write that Raoul Dal Molin Ferenzona was an artist who was “unfortunately forgotten and difficult to reconstruct due to the lack of biographical news and documentation.” It can be said that this is no longer the case: although still little or not at all known to the general public, Ferenzona’s personality, in the last five decades, has taken on a solid, robust, secure physiognomy, thanks to the great work that has been done first and foremost by Emanuele Bardazzi, the greatest expert on the artist, by art historians such as Francesca Cagianelli, and by scholars of early 20th-century literature for whom Ferenzona is an unavoidable presence. A young Italianist at the University of North Carolina, Danila Cannamela, has called him a " maudit artist.“ an overused adjective, but one that is well suited to the figure of Raoul Dal Molin Ferenzona, a painter and engraver (although better as an engraver than as a painter) with a tormented and restless life, alternating fortunes, varied and eclectic interests, a protean art ready to drink from any source, but always following a very firm conviction: art, for Ferenzona, is not investigation of the phenomenal, it is not registration of the real, it is not a search for impression. For Ferenzona, art is the form of dreams, it is poetry made flesh, it is the image of an imagination, it is thought painted, drawn, engraved. ”Imagination makes real what it invents." was the title of the sixth of the Paradoxes de la Science Supreme by Éliphas Lévi, an occultist and scholar of esotericism whom Ferenzona appreciated and whom he probably quoted in his many discussions with his colleagues, in early twentieth-century Rome, where theartist, Florentine birth, distant aristocratic origins, and cosmopolitan culture, had moved as early as 1904, at the age of twenty-five, to see the research of Giacomo Balla up close.

The results of so much work are summarized in an exhibition that, until March 15, 2025, the Pinacoteca Comunale di Collesalvetti is dedicating to Ferenzona(Raoul Dal Molin Ferenzona. Enchiridion Notturno. Un sognatore decadente verso l’occultismo e la teosofia, conceived and curated by Emanuele Bardazzi and Francesca Cagianelli) to reconstruct and reread the stages of the story of this singular artist, first investigated in two small exhibitions held between 1978 and 1979 in Rome and Livorno, curated by Mario Quesada, then followed by Bardazzi’s monograph organized by Gonnelli in Florence in 2002. In terms of the completeness of the exhibition itinerary, the breadth of the catalog and the volume of unpublished works, the Collesalvetti exhibition is nevertheless the most important one ever devoted to the Tuscan artist, who emerges from the review not only as a “decadent dreamer”, but also as a singular protagonist of the events of his time, even though at first glance he might seem a minor comprimario, a lingering pursuer, a gregario agitated by Symbolist tremors even after World War I had ended, a provincial Pre-Raphaelite thunderstruck by the word of Rossetti and Hunt when by then almost all the members of the fraternity had been in the ground for years. Yes, he often found himself pursuing, but one would be doing Ferenzona a disservice if one did not also consider him an artist capable of lightning-fast intuitions that in his career he alternated with tenacious stubbornness, if one did not consider him a visionary open to the’East, an artist “endowed with rare versatility of wit and vast culture” as he was called in his time, a man of letters capable of drawing or a draughtsman capable of writing. Enrico Crispolti had also taken it on board that Ferenzona, although coming from a Symbolist background with a markedly D’Annunzian bent, was in contact with the avant-garde (a point, this, that the exhibition touches on without delay).

It may be that his fortunes were not helped by this constant hybridization, this propensity for contamination, this closeness to literature that inevitably conditioned his critical reception: presented sometimes as a poet even before he was an engraver, sometimes as a poet tout court, sometimes considered a better draughtsman than a poet, at others a mere illustrator, Raoul Dal Molin Ferenzona probably paid the price for his versatility and eclecticism. It is, however, in the literary sphere that his formation is consummated, and it is by considering his habitual, long-standing frequentation of the literary milieu of his time that the ripest and juiciest fruits of his work as an artist can be gathered. The very title of the exhibition reflects this passion of his: theenchiridion was anciently a small manual, to be read while holding it in one’s hand. A “pocketbook,” we might say, adopting an anachronistic term, but one that can perhaps render the idea. In 1923, in Livorno, Ferenzona printed an extravagant, mysterious book, conceived together with another Symbolist, Charles Doudelet who, having arrived from Belgium on the shores of the Tyrrhenian Sea, had contributed to arousing interest in the esoteric in Livorno as well (and to Doudelet, it should be recalled, a careful exhibition was dedicated, again at the Pinacoteca di Collesalvetti). That book was entitled AÔB (Enchiridion notturno), was presented during a Book Exhibition organized in the halls of the Livorno gallery Bottega d’Arte, and represents one of the pinnacles of Ferenzona’s printed production, as well as one of the elements that most linked him to Livorno’s cultural circles. That book came, however, after other experiences.

In Rome in 1904, Ferenzona had arrived because he was attracted, it has been said, by Balla’s Divisionist research. Once he arrived in the capital, however, his interests shifted. Looking for Giacomo Balla, he would find Sergio Corazzini. With the crepuscular poet, Ferenzona formed a friendship of very short duration (Corazzini, younger but sicker, would die at only twenty-three, in 1907, ravaged by tuberculosis), but one of overflowing intensity. “Brother of art,” Ferenzona would call him in a prose dedicated to him after his death. We do not know how Ferenzona was painting at the time of his meeting with Corazzini, but we do know (from what he wrote in his early twenties, from the memoirs of those who were already with him at the time) that he was already interested in the occult and esotericism: the earliest pictorial evidence in the exhibition, a somewhat naïve but very convinced Woman with Hat and Bats from 1906, indicates with manifest clarity what Ferenzona’s disposition was in those years, a disposition that, albeit with frequent changes in reference points (first and foremost artistic ones), would sustain almost all of his production: Ferenzona’s was a soul that favored, Bardazzi writes in the catalog, “dreamy, mysterious and suggestive languages, the kind of aesthetic that expressed vague and unformulated sensations.” he was an artist who "declared his feeling of belonging to the variegated international Symbolist coté of which the Pre-Raphaelites, especially of the second generation, had been the precursors, giving rise to heterodox, more complicated and nonconformist filiations in England itself by queer artists close to Oscar Wilde such as Charles Ricketts and Aubrey Beardsley." Ferenzona was not isolated, nor was he lagging behind: the fascination with esotericism, in those years, was directing the researches of artists halfway across Europe; it was the answer to the grayness of industrialization, to the materialism of bourgeois society, to the alienation of existence in a world moving toward massification. And the glance toward earlier experiences was the result of a definite conviction: “No modern artist,” Ferenzona himself would write in 1923, “can boast of complete originality: the power of the great men of the past weighs on our brains, even that of a futurist.”

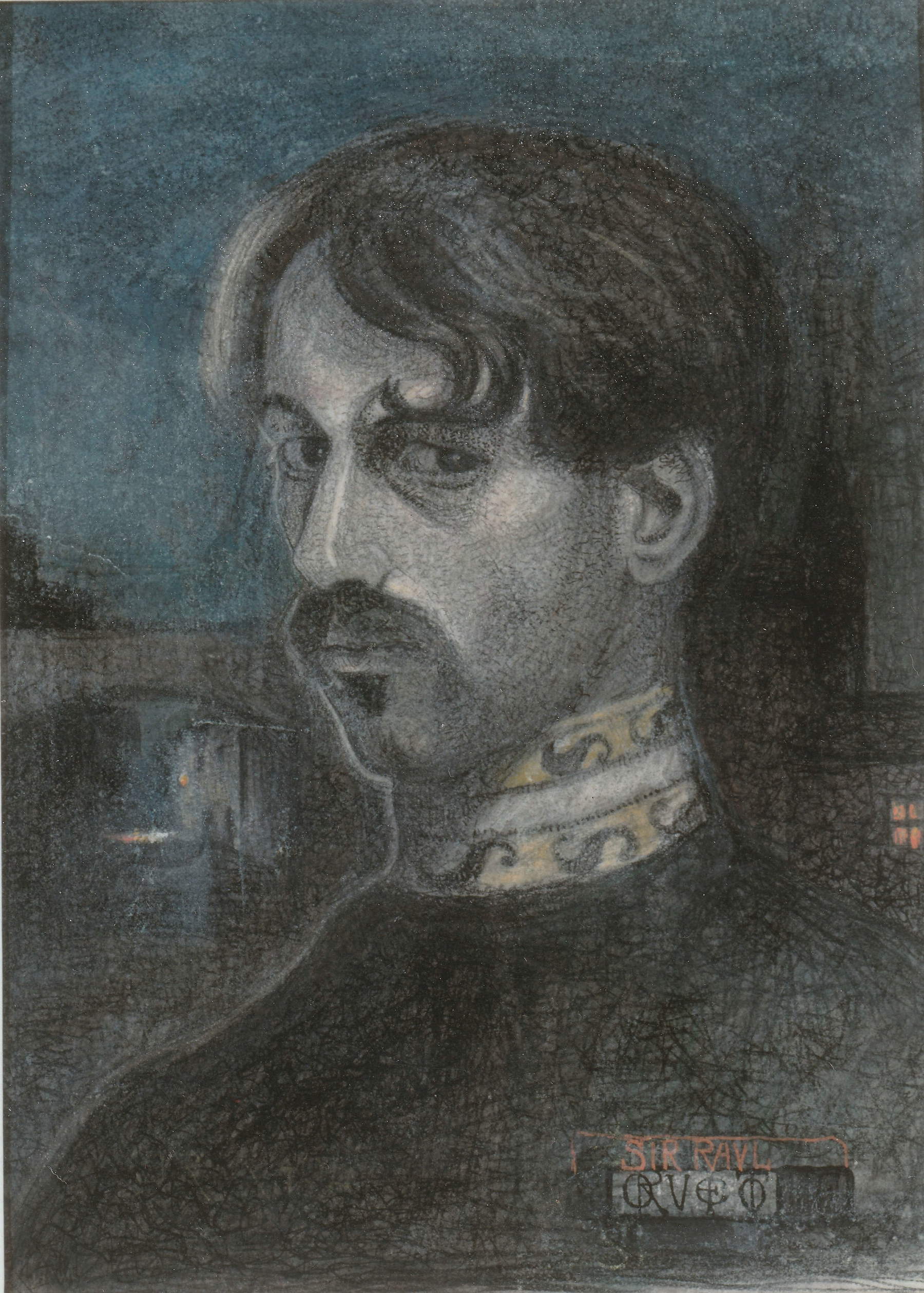

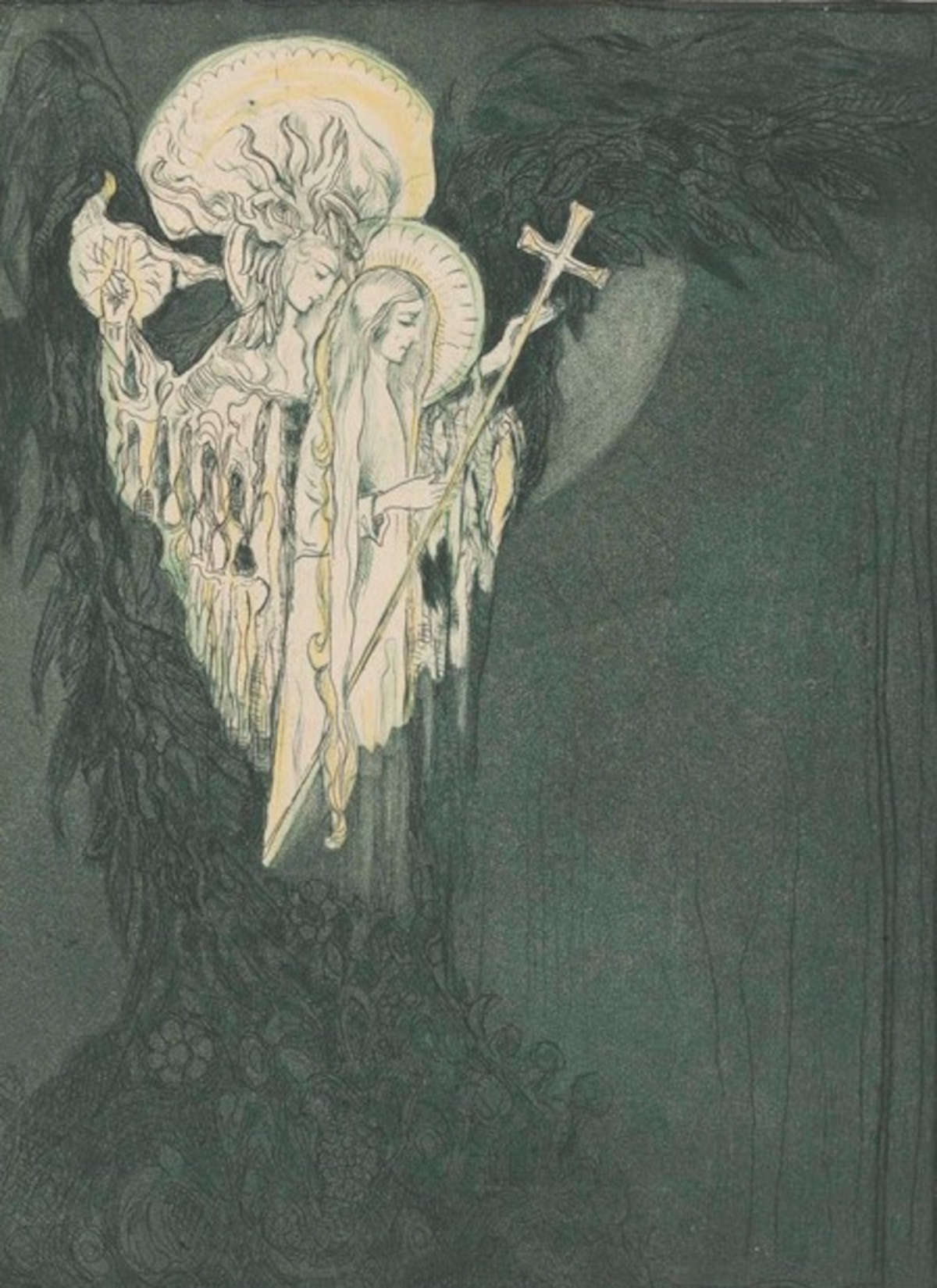

This adherence to a Pre-Raphaelite brand of symbolism was not an isolated moment in Ferenzona’s career: the fascination with that language runs through at least four decades, from the engraving Gravis dum suavis, a work of 1909 that the public of the Pinacoteca di Collesalvetti finds in the second room, a sweet portrait of a nun that looks to the Flemish of the fifteenth century and bears the title of’a D’Annunzio motto from the Triumph of Death, to works from the 1930s such as Fulvia and anAnnunciation that mix, albeit with some rigidity, recourse to early Renaissance sources with the dreamlike language of French Symbolism, passing through a singular novelty such as the triptych Ave Maria with an obvious British imprint. In between, Ferenzona had known so much more, and this can be seen by wandering around the first room of the exhibition, all dedicated to paintings: the Battle of the Medusas, for example, is a work that is presumed to have originated from the comparison with the underwater symbolism of Gino Romiti (another protagonist of a fine exhibition held in Collesalvetti between 2022 and 2023), in a Livorno indebted to Doudelet’s research. Again, The Eyes of Angels and The Summit of the 1920s certify Fenzona’s interest in the international researches of the Cubofuturists, Krishna Playing the Flute of 1933 sanctions the closest approach to Oriental philosophies, along with the probable portrait, circa 1930, of Jiddu Krishnamurti, the Indian philosopher close to the Theosophical Society who, in the 1930s, divested himself of his possessions, dissolved himself from membership in any organization, nationality or religion and spent the rest of his existence sharing his own worldview, all aimed at the quest for freedom from any conditioning. There is also no shortage of meditations on magic realism (the Portrait of an Old Lady), just as there is no shortage of looks turned to Belgian symbolism: the Masks of circa 1935 echoes the production of James Ensor, theetching Il n’y a rien de plus beau qu’une clef, tant qu’on ne sait pas ce qu’elle ouvre bears in its title a quotation from Maurice Maeterlinck, and then, in the second room, two unpublished tondi, a pair of enigmatic and rarefied pastel pencil drawings that evoke the atmospheres of Fernand Khnopff, another inescapable point of reference for Ferenzona, who also sought also his Bruges in Orvieto, where he resided for some time between 1908 and 1909 at the urging of his friend Umberto Prencipe, who had moved there(The Orvietane, along with the two pencil drawings, mark perhaps the closest he ever came to Khnopff). And if for the great Giancarlo Marmori, Khnopff was a “kind of D’Annunzio or Wilde in the plastic field,” one could say that Raoul Dal Molin Ferenzona was a kind of Sergio Corazzini moving between painting and engraving. The intimate, melancholic, crepuscular, dark vein that cloaks Raoul Dal Molin Ferenzona’s works flows from the very first self-portrait (a work from 1904-1907, therefore executed when the artist had the opportunity to associate with the man of letters), and it innervates much of his production. “Love, then, the shadow, and flee the light for, like the weather, it is naively malignant and terribly just. And with the shadow, love silence, for the shadow of words is silence. Love it as the Calvary of your Images, as the Cross of your Dream, as the Tomb of your Soul. It will know how to give you a star for a word, an eagle for a cry, a cry for a memory, always. You will live only by the Past: it will be in this way, far less grievous to you to flee hope and vain happiness”: so wrote Corazzini in his Exhortation to his brother. And Raoul Dal Molin Ferenzona’s art is an art of shadow and silence. Even in the choice of some subjects one glimpses the reflection of the friendship with Corazzini, to whom the artist would later, in 1912, dedicate La ghirlanda di stelle, a visionary collection of illustrated poems: Bardazzi noted that the poet’s existential (as well as physical) precariousness had led him to interpret his life "as the martyrdom of a predestined man in a sort of Imitatio Christi“ that prompted Ferenzona himself to ”internalize the Passion of Christ by reflecting in it his own tribulations and spiritual evolution" (and this as early as the Via Crucis of 1919).

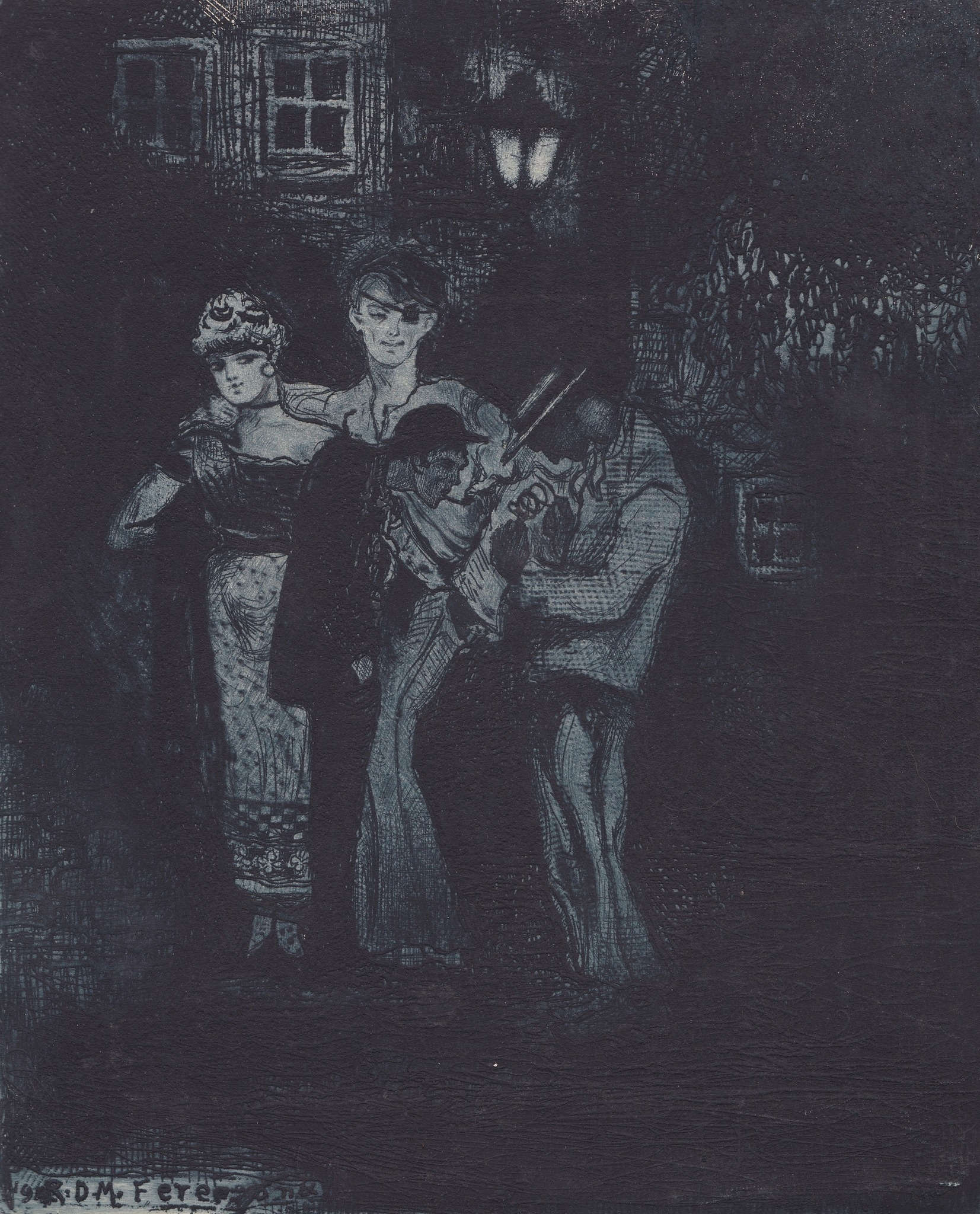

Inevitably, such a gloomy view of existence also reverberated in Ferenzona’s conception of woman, a conception on which, however, his interest in Baudelaire also weighed: now a demonic and luciferous female(The Sisters), now a distant, unapproachable, untouchable muse, shrouded in a haze of mystery(Woman with Moth), now a cold manipulator who dominates man, enslaves him, his puppet, as seen in The puppets, one of Ferenzona’s best etchings, indebted to Rops’s Dame au pantin , and in which one wanted to see the portrait of his beautiful wife Stefania Salvatelli, from whom he would later separate (the life of an artist like Ferenzona, after all, was not to be easily endured), but in whom Ferenzona saw a kind of his own feminine ideal, even salvific, since woman, in his works, is also a savior virgin (Ferenzona would also dedicate a portfolio of engravings, Life of Mary, to the Madonna). In general, for Bardazzi, Ferenzona’s female portraits seem to adhere to that “ambiguous” Baudelerian ideal, “of voluptuousness surrounded by sadness, all the more beautiful in that they are melancholy, weary, full of regret and refluent bitterness.”

One room of the review is all about exploring Raoul Dal Molin Ferenzona’s relationship with Livorno: an eminent personality, along with Doudelet, Romiti, Benvenuto Benvenuti, and Gastone Razzaguta, of that esoteric and spiritualist strand of Livorno art that sought, in the early 20th century, to propose analternative to the Factorian, post-Macchiaiola line, and which found a privileged meeting place in the Caffè Bardi (even Renato Natali, at first, was attracted by the group’s interests: The Thieves of 1914 is the point of maximum tangency between Natali and Ferenzona), Ferenzona was a protagonist in Livorno, from the exhibition at the Bagni Pancaldi in 1916 to the many participations in Bottega d’Arte’s exhibition schedules up to Ferenzona’s presence at the sixth and seventh exhibitions of the Gruppo Labronico in 1923 and 1924 (in the first he would exhibit the Life of Mary panels, in the second five works). It was in Livorno that Ferenzona, as mentioned above, published, for the types of the Belforte publishing house, with which he would have collaborated several times, the book AÔB (Enchiridion notturno) that gives the title to the exhibition, a collection, dedicated to Fryderyk Chopin (whom Ferenzona called “unforgettable, indivisible, invisible brother”), of twelve poems illustrated by as many pointed engravings, twelve “nomadic mirages” that, wrote Francesca Cagianelli in her catalog essay, dedicated precisely to Ferenzona’s Livorno presence, “amplified Ferenzona’s nocturnalist vocation in a Rosicrucian direction.” Francesca Cagianelli’s contribution also gives an account of an episode, hitherto unknown, which has emerged from a search following a trace in the archives of the National Gallery in Rome: Ferenzona, in Livorno, was also the set designer of some musical performances for children with a fairy-tale theme(Nel regno delle farfalle, Natale in soffitta and Il giardino incantato) that were staged at the city’s Teatro dei Piccoli.

The exhibition bids farewell to Ferenzona with some of his macabre works (such as A cup of tea, The Drop of Poison and The Perfidious Vegetables) that hark back to a world of spells and demonic anxieties capable of reflecting, in some ways, his Prague experiences, and to which, however, an illustrated postcard, The Dawn Greeting, which is instead filled with hope and comes at the end of the journey like a clear morning after a stormy night, like a rosy sun making its way in the midst of a gloomy sky covered with black clouds (“Consider this day / For it is life / True life of life // In its fleeting course / This day encompasses / All the varieties, / All the realities / Of your existence, / The happiness of flourishing, / The glory of action, / The splendor of beauty. // For yesterday is but a dream / And tomorrow / Is but a vision // But today well lived, / Makes of every day passed / A dream of happiness, / Makes of every day to come / A vision of hope / So consider this day.”) A last room, at the end, gathers a large group of engravings that makes explicit the sources, inspirations, and cues on which Ferenzona’s art was formed: here are graphics by Rops, Khnopff, Georges De Feure, and the Prague group Sursum (Josef Vachal, František Kobliha and Jan Konůpek). Of particular note is the famous poster of the first Salon de la Rose+Croix in 1892, a work by Carlos Schwabe who has often been the protagonist of even recent reviews on the themes of mystical and spiritualist symbolism.

The exhibition on Raoul Dal Molin Ferenzona closes in Collesalvetti a cycle that began with Doudelet and continued with Romiti, Macchiati and Benvenuti, with which curator Cagianelli has explored many of the rivulets of Tuscan, and specifically Tyrrhenian and Leghorn, symbolism of the early twentieth century: a palimpsest that has ringed important exhibitions, supported by solid projects, full-bodied research work, the discovery of numerous unpublished works (the exhibition on Ferenzona is no exception, perhaps the richest in unpublished works and novelties of the cycle: some of these unpublished works have been accounted for here), and always accompanied by meetings and conferences that have deepened the themes presented in the rooms. Raoul Dal Molin Ferenzona. Enchiridion Notturno is a scientifically impeccable, eventful and fascinating exhibition, which was able to reconstruct an early twentieth-century Italian event that was perhaps not forgotten, but certainly set aside, and in any case little known to the general public, at the close ofa cycle that was held in a small museum, but which, even in economy of means and resources, held high the level of what has been organized in the Livorno area in recent years. It is increasingly rare to see exhibitions of this kind in Italy, which are able to shed light on little-known episodes of an art history that may be local but which is intertwined with indissoluble ties to national vicissitudes, which provide the public with opportunities for vertical insights into artists and events fundamental to the history of the area, which make use of robust scientific apparatuses, small milestones in the historiography on the relevant artists. In the last four years, in little Collesalvetti, important pages of Italian art history of the early 20th century have been written. Now it is good that this work continues and, indeed, perhaps manages to expand to the capital city as well.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.