by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 05/11/2017

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'Ambrogio Lorenzetti' in Siena, Complesso di Santa Maria della Scala, October 22, 2017 to January 21, 2018.

To get an idea of how important and how much esteem the art of the great Ambrogio Lorenzetti (Siena, c. 1290 - 1348) has enjoyed since ancient times, a simple exercise might suffice: scrolling through Lorenzo Ghiberti ’s Commentarii and dwelling on the pages devoted to the Sienese fourteenth century. The surprises are several: first of all, we would discover that Ghiberti considered Lorenzetti not only “otherwise learned than none of the others,” but even “much better” than another of the greatest exponents of the Sienese school of the time, Simone Martini, a name with which perhaps art lovers are more familiar. Above all, someone might notice that, in the Commentarii, the space devoted to that “famosissimo et singularissimo maestro” who was Lorenzetti, is greater, if only slightly, than that reserved for a pillar of Italian art history such as Giotto, an artist who, needless to say, needs little introduction. We might almost be astonished by such consideration, since critical fortune has arisen more for Simone and Giotto than for Ambrogio, whose name, in the course of history, has known ups and downs: held in high esteem in the Renaissance, little considered in the seventeenth century and almost forgotten in the eighteenth century, reevaluated toward the end of the century and again in vogue in the nineteenth century, snubbed by Berenson and at first even by Longhi, returned to scholarly attention around the middle of the last century.

And even today there is a certain resistance to considering Ambrogio Lorenzetti beyond what is the work that more than any other has consigned him to the history of art, namely the cycle of good and bad government that adorns the Sala dei Nove in Siena ’s Palazzo Pubblico and that so much glory procured and continues to procure its author. It is no coincidence that the last monograph on the painter is an outdated work (it was published in 1958, and the author was George Rowley, an American scholar at Princeton University who made a decisive contribution to today’s reappraisal of Lorenzetti’s genius) and that no monographic exhibition had ever been devoted to him until now. To fill in the gaps, to focus attention on the whole production of the great Sienese artist, to take stock of the studies concerning him and, ultimately, to try to establish as complete a discourse as possible on Ambrogio Lorenzetti, comes this year an exhibition of paramount importance, entitled, quite simply, Ambrogio Lorenzetti, underway in the spaces of the Santa Maria della Scala complex in Siena.

An event that the three curators, Alessandro Bagnoli, Roberto Bartalini and Max Seidel, do not hesitate to call unprecedented. But it is not a mere commercial formula used to attract hordes of visitors to the shadow of the Duomo. The Siena exhibition is truly unique, and not only for the fact that it represents the first monographic exhibition ever dedicated to Ambrogio Lorenzetti. Indeed, at Santa Maria della Scala we have the opportunity to see gathered together almost the entirety of the artist’s movable production-an occasion that will probably not be repeated, or at least not in the near future. We have the opportunity to see the torn frescoes of Montesiepi (whose restoration carried out for the occasion ended a few months ago) organized in an arrangement that takes us ideally inside the hermitage of St. Galgano, first at ground level to look closely at the frescoes of the first register, and then as if we were three feet high to look at the lunettes in a way otherwise impossible without climbing any scaffolding. We have the opportunity to enjoy an exhibition itinerary that makes use of a few but timely and effective comparisons, that frames Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s production in a chronological sense and presents it with a very clear and sober didactic apparatus, as well as, of course, with a project endowed with a high scientific rigor. An itinerary that, it is worth pointing out, is particularly suitable for a heterogeneous public, which will thus be able to familiarize itself with the many faces of Ambrogio Lorenzetti, who in the Sala dei Nove was a painter capable of achieving the most admirable result of the time in a fresco of civil destination (so wrote Alessandro Conti), but who was also a painter capable of surprising iconographic inventions, a learned connoisseur of the literature of his time, a refined, versatile and innovative artist.

There is then a further reason for interest: Siena, in the years of crisis, had lost the leading role in Italian cultural life that it had long held. Just thinking in the area of exhibitions, the last major event had been the exhibition on the early Renaissance in Siena seven years ago. This year, the exhibition on first the “good century of Sienese painting,” then the Salini collection, and now the monographic exhibition on Ambrogio Lorenzetti, and again the securing and reopening of Palazzo Squarcialupi, the portion of the Santa Maria della Scala complex that houses the exhibition and whose rooms are as suitable as ever for large-scale exhibitions, make up a picture that could make us remember 2017 as the year of the city’s cultural revival. Any consideration is obviously premature, but the premises bode well.

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti exhibition in Siena |

|

| A room from the Ambrogio Lorenzetti exhibition in Siena |

|

| Corridor with works by Ambrogio Lorenzetti at the exhibition in Siena |

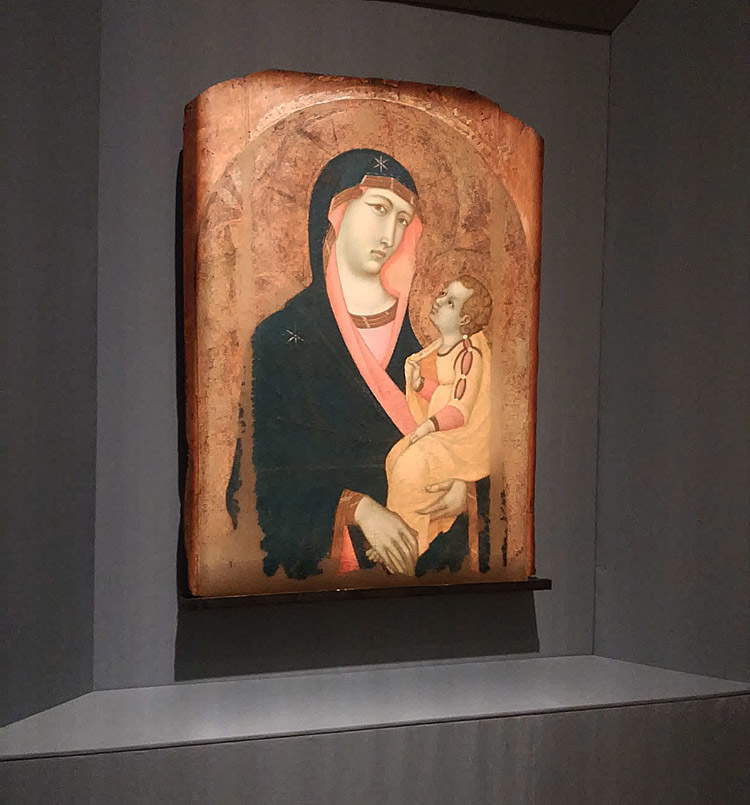

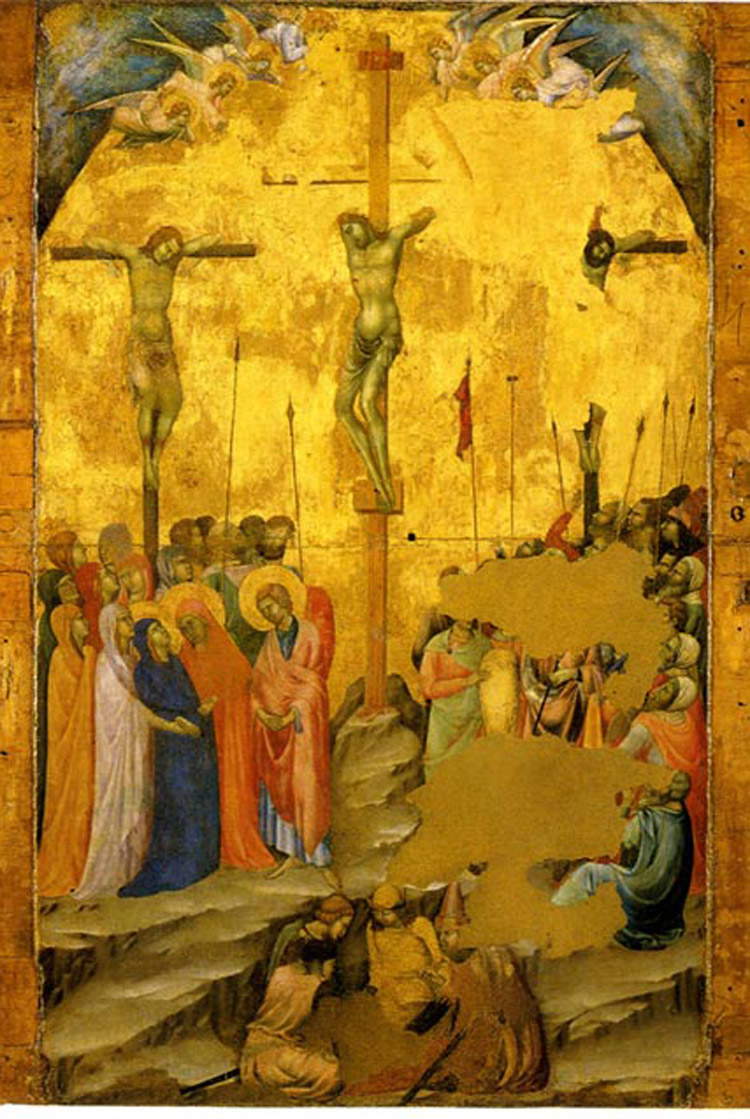

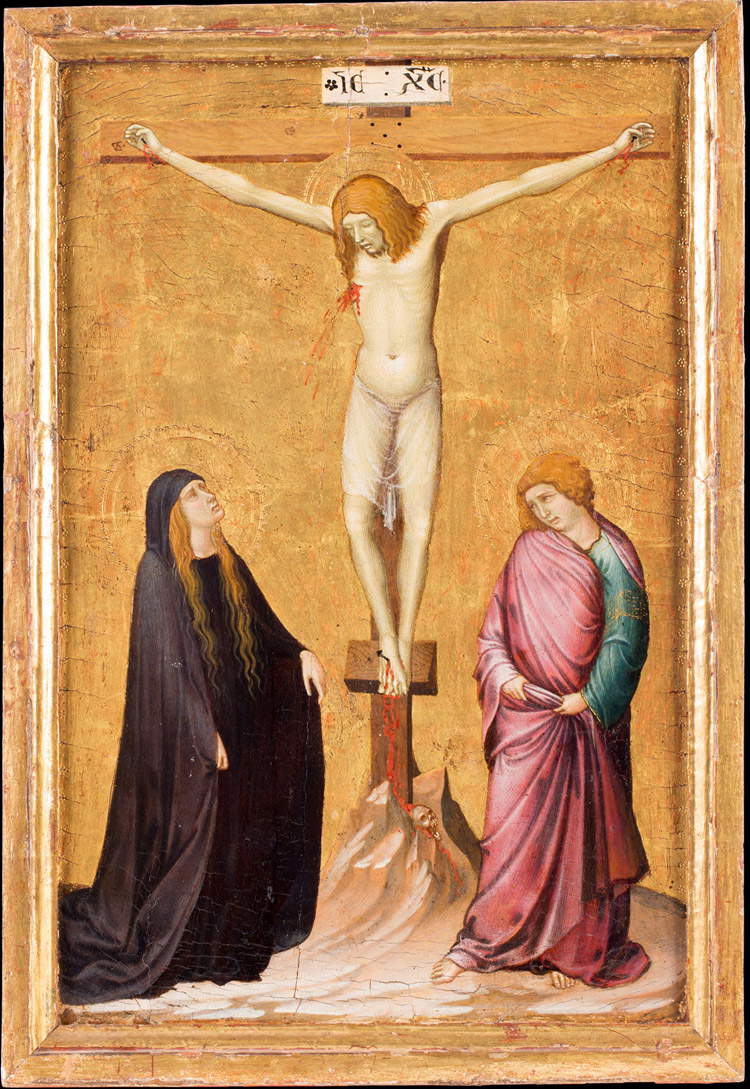

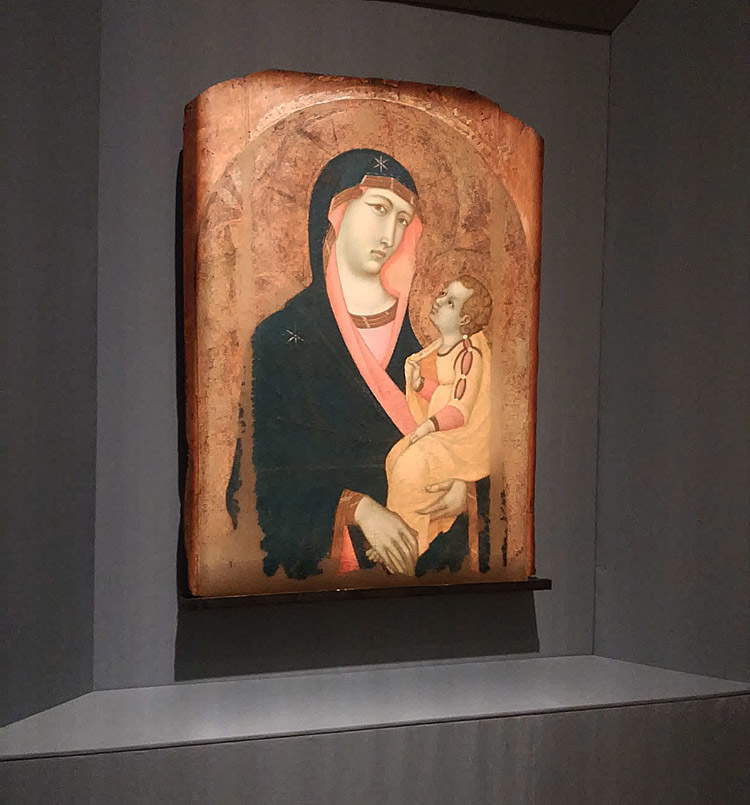

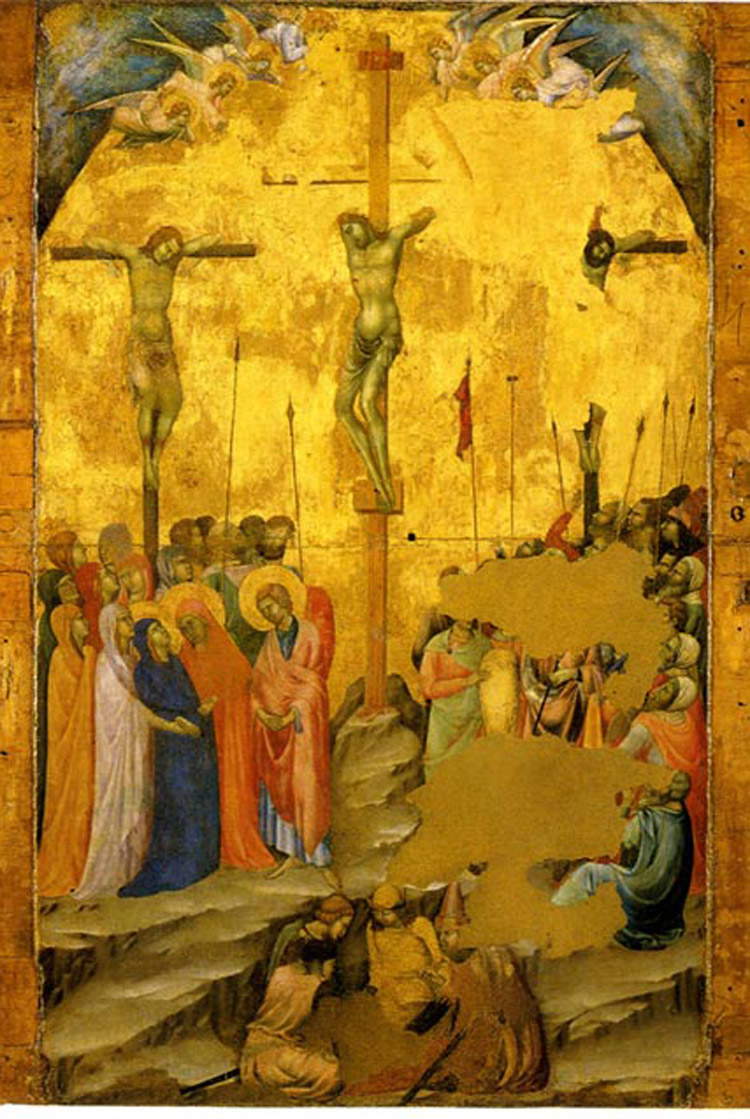

The exhibition itinerary opens with a reconstruction of the context within which Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s genius was born and developed. And it is left to his brother Pietro to initiate it: on the right, as we enter the first room, we find the Madonna and Child of Castiglione d’Orcia, a slender Virgin with a Duchy-like flavor (the work can be traced back to the first phase of Pietro Lorenzetti’s career) who holds in her hands a baby Jesus who, in turn, turns to her with a lively expressiveness, indicative of how the new generation, to which Ambrose also belongs, is already taking a different path from that traced by the great master, under the banner of a more defined plasticism and a more natural rendering of the affections. It is necessary to keep this Madonna in mind for when one encounters Ambrose’s works in later sections. Then there is Simone Martini’s firm and traditional Redentore benedicente (Blessing Redeemer ), close to the master to the point that several scholars have considered it an early work, while a date of 1318-1320 is proposed in the exhibition, due to the presence of details similar to those detectable in works painted by the artist in that time frame. To conclude the roundup of the great Sienese painting of the 14th century, we find Duccio di Buoninsegna himself: the Stories of the Passion from the Massa Marittima Majesty, a work that is, moreover, decidedly problematic given the stylistic dissimilarity that characterizes it, leaves the field open to hypotheses that want a young Ambrose to be particularly impressed by the crucifixion scene, of which we find some characteristics in his first work that we meet in the exhibition, the Crucifixion of the Salini Collection.

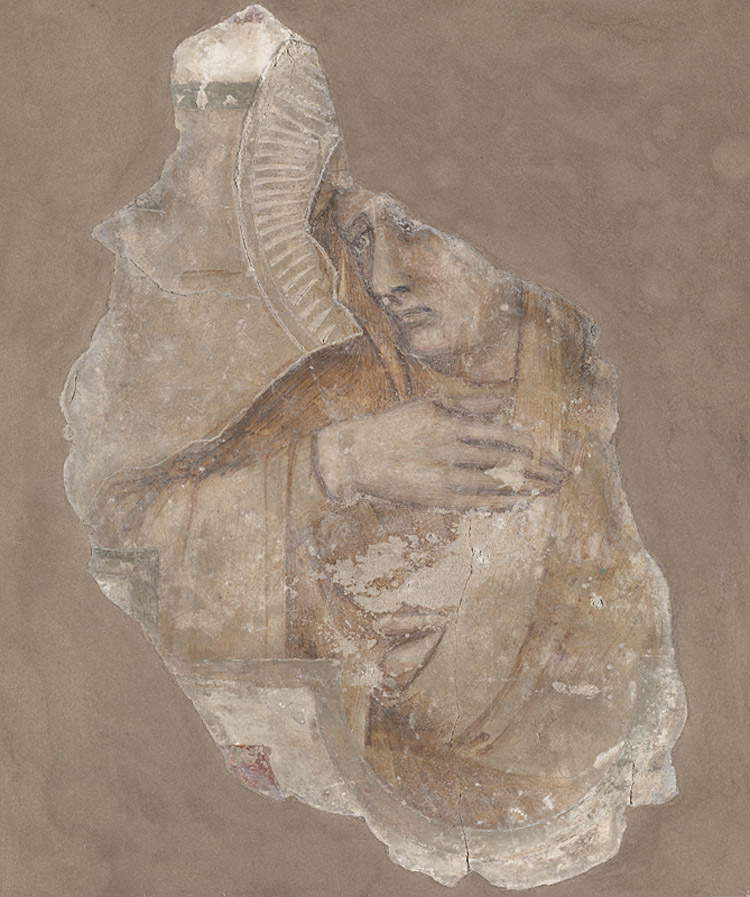

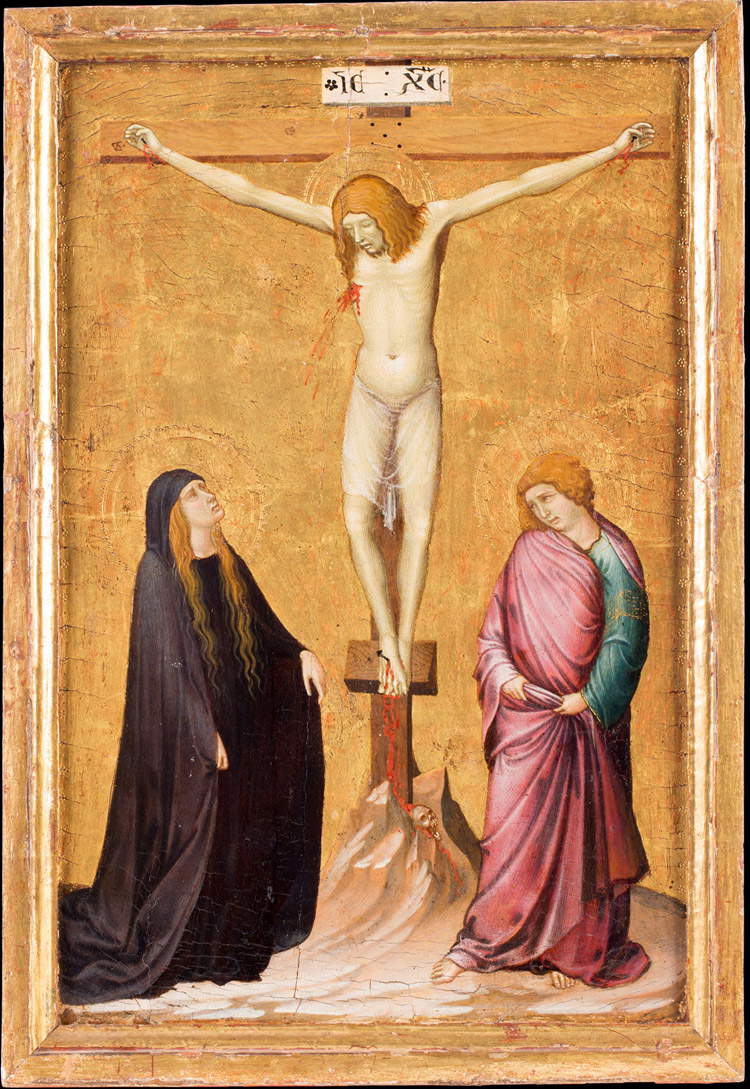

The latter is a small picture, authoritatively first referred to Ambrose by Miklós Boskovits in 1986, and is distinguished as much by its debts to Duccio di Buoninsegna (note the landscape within which the scene takes place, quite similar to that which could be appreciated in Duccio’s Stories of the Passion, but also the figure of John the Evangelist, which is clearly inspired by the angels of Duccio’s Crucifixion in Massa Marittima) as much as by a new sensibility made evident by certain formal solutions (the lowered point of view of the crucifixion, for example) and by certain details such as the connotations of the Virgin, who is almost identical to the Madonna we find in the Crucifixion in the basilica of San Francesco in Siena or the fragmentary Sorrowful Madonna in the chapter house of San Francesco, both works by Peter: the latter, moreover, is featured in the exhibition (it arrives on loan from the National Gallery in London). Dated 1319, on the other hand, is the sumptuous Madonna di Vico l’abate, preserved at the Museum of Sacred Art in San Casciano in Val di Pesa: The volumetric fullness of the Madonna, capable of contrasting the severe frontality of the archaic taste that is in turn mitigated by the lively gaze of the Child, has given rise to more than one debate among scholars about possible links with Giotto’s painting, which the artist certainly knew (probably also through Simone Martini and Pietro) and to which the attempts at three-dimensionality that the throne in perspective reveals would also seem to refer. Certainly it is precisely that contrast between the mother’s fixity and the son’s restlessness (note then the splendid detail of the little right hand pulling the veil from underneath, allowing a glimpse of the forms beneath the red folds) represents one of the first iconographic innovations experimented with by Ambrogio Lorenzetti.

|

| Pietro Lorenzetti, Madonna and Child (c. 1310-1315; tempera, gold and silver on panel, 73 x 52 cm; Castiglione d’Orcia, pieve dei Santi Stefano e Degna) |

|

| Simone Martini, Blessing Redeemer (c. 1318-1320; tempera and gold on panel, 38.3 x 28.5 cm; Vatican City, Vatican Museums) |

|

| Duccio di Buoninsegna, Stories of the Passion, detail with the Crucifixion scene (in progress 1316; gold and tempera on panel, 161.5 x 101.5 cm; Massa Marittima, Cathedral of San Cerbone) |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Crucifix with Mary and St. John the Evangelist Mourning (c. 1317-1319; tempera and gold on panel, 33.5 x 23 cm; Asciano, Castello di Gallico, Salini Collection) |

|

| Pietro Lorenzetti and workshop, Mourning Madonna (c. 1320-1325; detached and applied fresco on rigid honeycomb-textured support, 39 x 30 cm; London, National Gallery) |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Madonna and Child Enthroned (1319; tempera and gold on panel, 148.5 x 78 cm; San Casciano in Val di Pesa, Museo d’Arte Sacra “Giuliano Ghelli”) |

The Virgin loses her rigidity, acquiring a maternal lovingness, and becomes again more slender, but equally firm in her volumes, in the marvelous Madonna of Milk in the Museo Diocesano in Siena, where the vivacity of the Child, kicking with unusual naturalness as she grasps her mother’s breast with all-childlike voracity, touches one of her peaks: further achievements toward a painting closer to the viewer’s sensibility, a painting that, Enzo Carli stated in the 1960s, demonstrates, compared to Peter’s, “a more complex, subtle and variegated sentimental disposition,” to which must be united that “sharper and more alacreous spirit of research in both the stylistic and iconographic fields” to which reference has been made several times. An experimentalism that led Ambrose to measure himself also with the art of glass: the Sienese exhibition also presents us with a Saint Michael the Archangel painted on glass, whose face, with its almost almond-shaped eyes and the chiaroscuro highlighting the chin and neck, refers without too many doubts to the Madonna del Latte itself, leaving open the hypothesis that the two works, though without having footholds for a sure and incontrovertible dating, were created at close range.

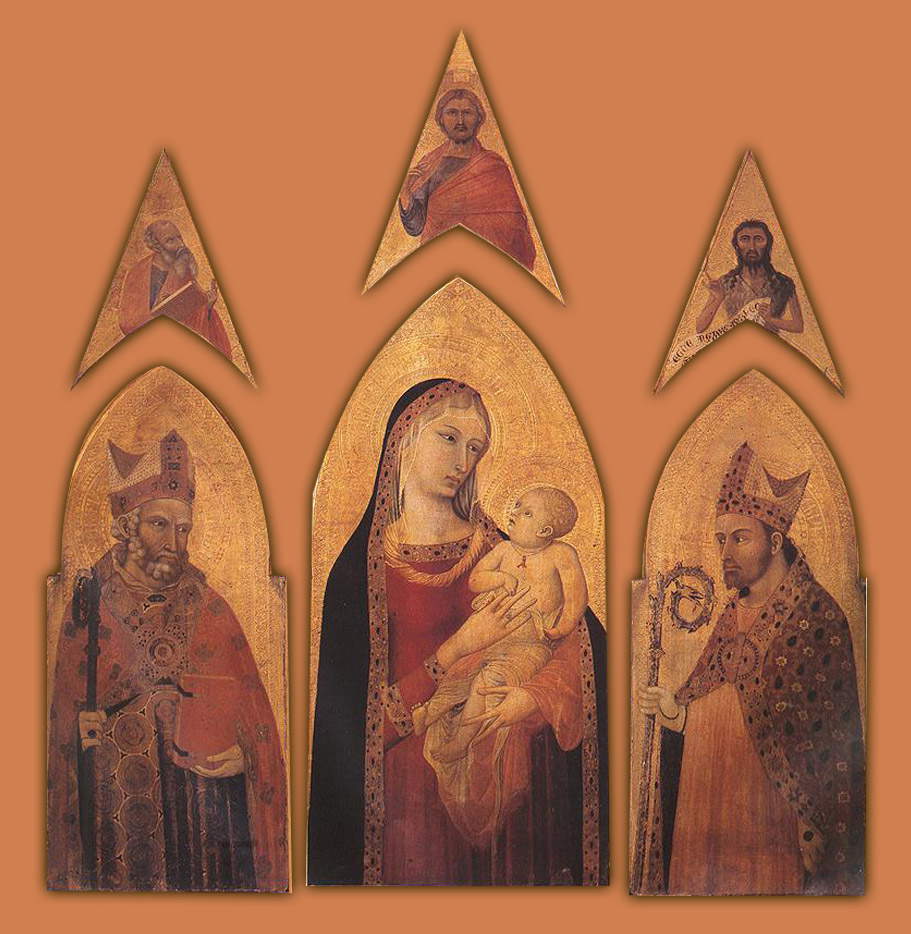

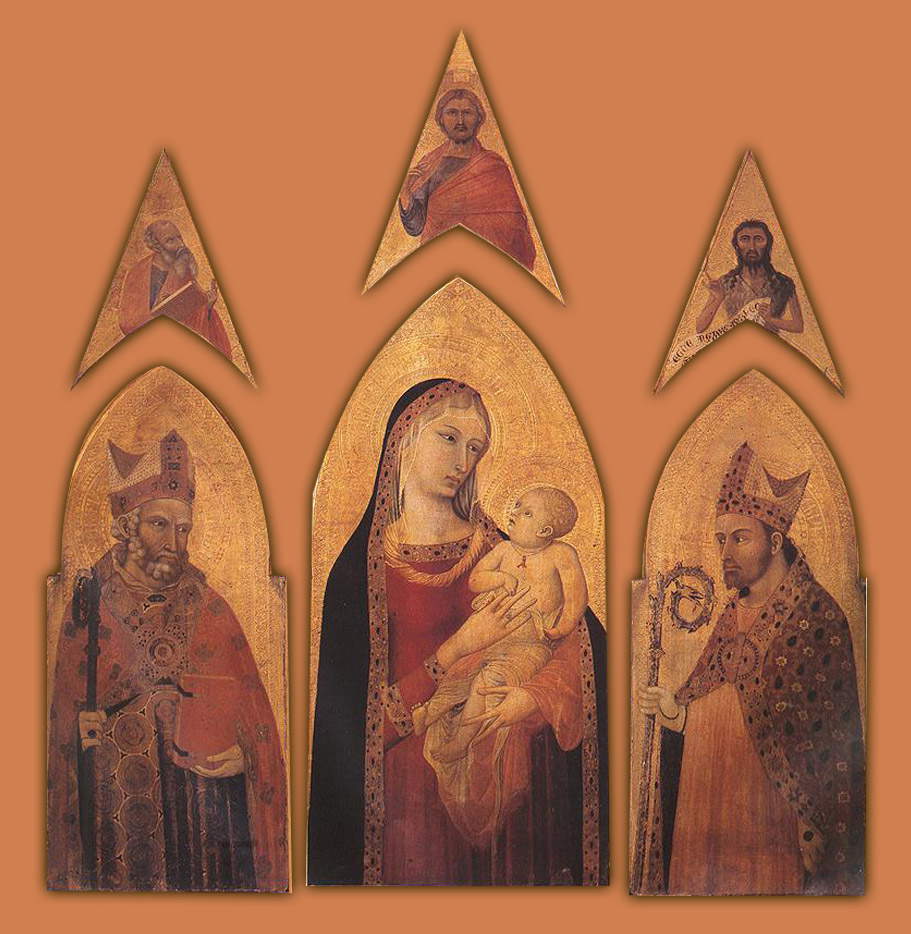

By contrast, it is a staple of Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s production that the visitor encounters in the next room, the famous Triptych of St. Proculus, which is part of the group of works restored for the exhibition. The three panels feature a Madonna and Child in the center, and on the sides St. Nicholas on the left and St. Proculus on the right: the three figures are surmounted by cusps presenting, respectively, the Blessing Redeemer and Saints John the Evangelist and John the Baptist. A firm point, and yet not immune to problems, since the three panels were divided when the church of St. Prokulus in Florence underwent modernization works, with all that ensued: commentators, seeing the solitary side panels, attributed the figures of the two saints to other hands, while the Madonna went missing. Clarity needed the insight of Frederick Mason Perkins, who in 1918 re-established the Lorenzettian authorship of the two side panels, and that of Giacomo De Nicola who, in the 1920s, tracked down the Madonna, which had been purchased in 1915 by Bernard and Mary Berenson on the antiques market, and traced it back to the dismembered Ambrose triptych. Berenson then decided to donate the panel to the Uffizi in 1959, so that the work could finally be reunited. A problematic work, then, also from a stylistic point of view, since a certain qualitative gap in the figures of the two side saints has led some to speculate on the presence of collaborators. However one wants to think of it, it is undeniable that Ambrose, in this triptych of his, welcomes a preciosity andformal elegance that bring his art closer to that of Simone Martini: the more slender figures, the taste for refined ornaments typical of Sienese art of the time, which was unparalleled in the refinement of its decorations (note the liturgical vestments of the two saints, decorated with motifs of the greatest finesse, the crosier of St. Proculus, the edging of the Virgin’s mantle, and even the veil gathered on her neck), are signs that well highlight this relationship. Ambrogio, then, certainly does not want to lose the freshness that characterizes the rendering of feelings: the play of hands between the Madonna and the Child, with her holding him affectionately and casually on her right arm, and with him teasing with his mother’s index finger, is a detail endowed with great emotional force.

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Madonna of Milk (c. 1325; tempera and gold on panel, 96 x 49.1 cm; Siena, Museo Diocesano) |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Madonna of Milk, detail |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, St. Michael (c. 1325-1330; polychrome glass painted with grisaille and partly sgraffito, assembled with tin-soldered lead profiles, 82 x 63 cm; Siena, Palazzo Pubblico, Museo Civico) |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Triptych of Saint Proculus (1332; tempera and gold on panel, 169.5 x 56.4 cm the central panel, 146.5 x 41.4 cm the side panels; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

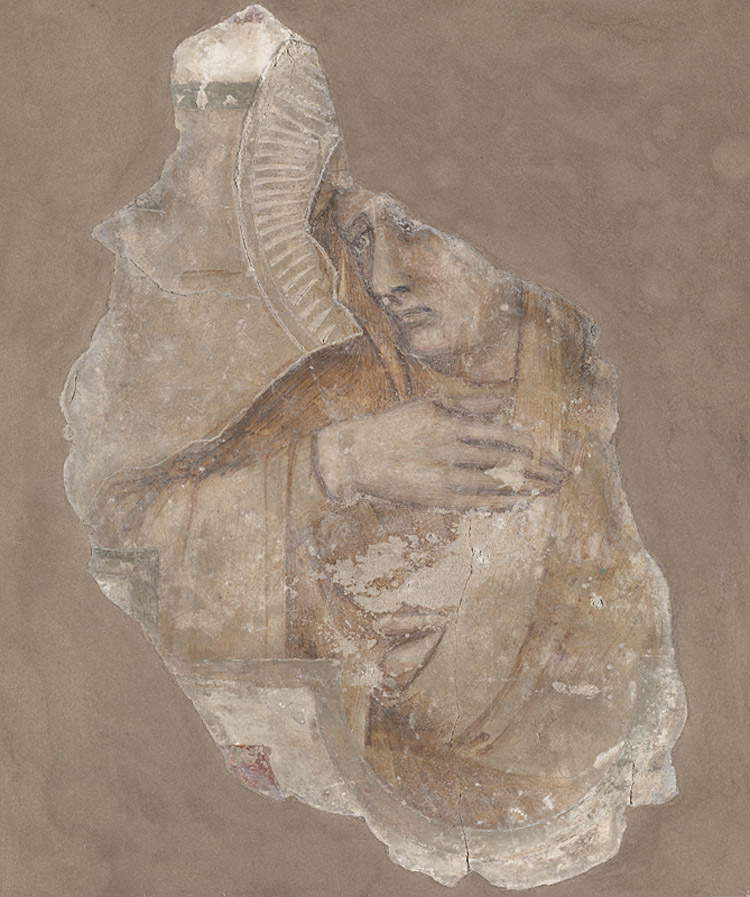

A narrow passageway then leads us into the first of two rooms devoted to the frescoes of the Hermitage of Montesiepi. The curators wasted no opportunity, in presentations and interviews, to recall how much of a stir the cycle that Ambrogio Lorenzetti imagined for the hermitage built on the site where Saint Galgano spent his own hermitage caused among patrons. We notice this by looking at the scene of theAnnunciation, with the figure of the Virgin repainted in a more canonical and traditional way, after the artist had come up with a highly original iconographic solution, which the patrons probably did not like: Mary was initially clinging to the column, frightened by the presence of the angel. Lorenzetti, explained scholar Eve Borsook in her 1969 contribution (which the catalog gives us an account of: the file devoted to the Montesiepi frescoes compiled by Max Seidel and Serena Calamai is actually, in terms of its consistency and level of detail, an essay that could easily stand alone), drew on the descriptions of pilgrims returning from the Holy Land who recalled how in the room where, according to tradition, the Annunciation had taken place, there was the column to which the Madonna clutched in fear when the announcing angel arrived. Also belonging to the scenes in the lower register, which we see in the first room, is the view of Rome that recalls the pilgrimage that Saint Galgano made to the Eternal City: a refined urban view where the mass of Castel Sant’Angelo, a building dedicated to Saint Michael, Saint Galgano’s protector, stands out. We see the archangel on the top of Castel Sant’Angelo, depicted in the act of putting away his sword: a further invention by Ambrogio Lorenzetti intended to recall the gesture of Saint Galgano who, spurred on by Saint Michael, abandoned his life as a knight to give himself to asceticism and meditation.

The encounter between St. Galgano and St. Michael is summarized in the lunette frescoes, which we find in the next room: Galgano, still dressed as a knight, proceeds toward Michael bringing him the sword in the rock (the one that we can still observe today in the hermitage of Montesiepi), to seal the definitive abandonment of his previous warlike existence to embrace a life of monastic rigor. With his hand, the archangel points to the central lunette, where we find a depiction of the Madonna enthroned among saints, an allusion to one of Saint Galgano’s visions: central is the meditation on the theme of redemption, alluded to by the foreground figure of Eve, placed at the foot of the Virgin’s throne (a further iconographic invention by Ambrogio Lorenzetti, destined to suggest several artists of later generations) and bearing a scroll in the vernacular explaining to the viewer how Eve sinned “pe(rc)hé passion ne soferse Xr(ist)o che questa Reina sorte nel ventre a nostra redentione.” Having brought together all the frescoes in an arrangement that recomposes their arrangement inside the hermitage is an indispensable prerequisite for a full understanding of the scope of the cycle, which Ambrose conceived according to a substantial unity of composition, well illustrated in the catalog: in fact, the artist did not want to give an account of the events of the saint according to a paratactic scansion, but aspired to “condense all the narrative ideas into a single figurative conception: Mary Queen enthroned with the celestial court that unifies the three lunettes.” And it is within this unity that the episodes of Saint Galgano’s life find their place.

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Montesiepi Frescoes, Annunciation (1334-1336; 238 x 441 cm; fresco, Chiusdino, church of San Galgano in Montesiepi) |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Montesiepi Frescoes, View of Rome (1334-1336; fresco, 240 x 598 cm; Chiusdino, church of San Galgano a Montesiepi) |

|

| The environment showing the lunettes of Montesiepi |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Montesiepi frescoes, detail of the figure of Eve |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Montesiepi frescoes, detail of the encounter between Saint Galgano and Saint Michael |

It continues with masterpieces from the 1930s: particularly happy the idea of having placed in dialogue the Badia a Rofeno Triptych, a work preserved at the Museo Civico Corboli in Asciano and endowed with a lively narrative rhythm in which Ambrogio opposes “the excitement of the central panel with the hieratic calm of Saints Bartholomew and Benedict on either side of him” (so in the catalog the very young Marco Fagiani, who for the work proposes a date close to 1337), with the four saints of the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Siena: these are in fact two related works, and the triptych from Asciano, in the 1920s, was assigned to Ambrogio Lorenzetti precisely because of the similarities of its figures with those of the four Sienese panels, which in turn are similar to the saints of the triptych of San Procolo, from which, however, they are distinguished by a greater plasticity. The room is closed, at the back, by the spectacular Massa Marittima Majesty, a work filled with literary references. The depiction of the three theological virtues (Faith, Hope and Charity) at the feet of the Madonna, on the three steps of the throne, which are presented in their respective three colors (red for charity, green for hope, white for faith), is pregnant with references to literature, from Dante Alighieri ’s Commedia (Canto XXIX of Purgatorio: “Three women walking around, from the right wheel, / came dancing: one so red / that she barely pierced inside the fire she noticed; / the other was as if her flesh and bones / had been made of emerald; / the third seemed to be snow that had been moved”) to Jacopone da Todi (“Amor de caritate, perché m’hai così ferito? / Lo cor tutt’ho partito, ed arde per amore. / Arde ed incende, nullo trova loco: / non può fugir però ched è legato; / sì se consuma como cera a foco”), while in the figures of the saints, who appear to us individually characterized, we can see a certain taste for narrative, particularly evident if we observe the figure of Saint Cerbone, the patron saint of Massa Marittima, accompanied by geese, his typical iconographic attribute: in fact, legend has it that the saint spoke to some wild geese, and the latter followed him, accompanying him to Rome.

We turn back and enter the last corridor, where we find the works of the last years: the late 1930s and early 1940s mark the great success of Ambrogio Lorenzetti, who was engaged in the Sala dei Nove in the Palazzo Pubblico, and at the same time active for commissions that came to him from all over the territory of the Republic of Siena (it is, moreover, in the Sienese area that most of his known production is still preserved). Among these, the polyptych of the Magdalene, attributed to Ambrose in the nineteenth century and possibly coming from the convent of Santa Maria Maddalena in Siena, is interesting: in the exhibition it has been reconstructed, complete with a “communichino,” the grating that allowed the cloistered nuns to hear Mass. The figures are characterized by that search oriented toward even firmer volumetries that marks the extreme outcomes of Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s art, and which we punctually find again in the last works that the Sienese exhibition presents to us, notably the one that concludes the itinerary, theAnnunciation from Siena’s Palazzo Pubblico (it is a work of civic commission, as evidenced by the names of the authorities inscribed in the base of the panel) and currently kept at the Pinacoteca Nazionale, a work that “concordantly represents today one of the masterpieces of Lorenzetti’s maturity, in which a meditated sense of space is happily combined with the refined exquisiteness that pervades the work” (so Alessandra Caffio in the catalog entry). In fact, unprecedented here is the search for a three-dimensionality to which the artist tends with a spatial setting that sees its main protagonist in the checkered floor that the painter tries to foreshorten in a perspective that is albeit empirical, but for the time extremely coherent and innovative. It is the clearest symptom of a greater tendency toward naturalism that, without renouncing the refinement that looks to Simone Martini (note the figure of God the Father made in sgraffito with goldsmith’s preciosity), connotes Ambrose’s later works, as is likewise demonstrated by the volumetries of the figures and certain solutions such as the thumb that the archangel Gabriel points toward himself and the sculptural rendering of the throne of the Virgin. It is impossible to leave the exhibition without taking a look at a peculiarity such as the wooden cover of the revenue and expenditure register of the Gabella (an ancient magistracy of the Municipality of Siena) bearing an allegory of the city, depicted as a canute man enthroned dressed in the colors of Siena, black and white (personification of the Municipality, or good government) who rests his feet on the Capitoline she-wolf, symbol of Siena as an allusion to the mythical founding of the city by the sons of Remus. It should be pointed out, however, that not all critics agree in ascribing the blanket preserved in the State Archives of Siena to Ambrogio’s production.

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Triptych of Badia a Rofeno (c. 1332-1337; tempera and gold on panel, 123.1 x 102.5 cm the central panel, 103.8 x 45 cm the side panels, 88.5 x 91.8 cm the central cusp, 43 x 35 cm the side panels; Asciano, Museo Civico Archeologico e d’Arte Sacra di Palazzo Corboli) |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Maestà (gold, silver, lapis lazuli and tempera on poplar wood panels, height 161 cm the central panel, 147.1 the side panels, width 206.5 cm; Massa Marittima, Museo d’Arte Sacra) |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Majesty, detail of the figure of Charity |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Polyptych of Magdalene (c. 1342-1344; tempera and gold on panel; Siena, Pinacoteca Nazionale) |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Annunciation (1344; tempera and gold on panel, 121.5 x 116 cm; Siena, Pinacoteca Nazionale) |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Annunciation, detail |

|

| Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Allegory of Siena, Gabella Register Cover (1344; tempera on panel, 41.8 x 24.7 cm; Siena, State Archives) |

Visitors can continue their journey through Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s production outside the exhibition, in the city, where the frescoes of Palazzo Pubblico, those of the basilica of San Francesco, and the Majesty of St. Augustine await them, an ideal continuation of the exhibition that unfolds in the halls of Santa Maria della Scala and which, as anticipated at the outset, represents one of the outstanding exhibitions of the year, as well as one of the most important exhibition events for the art of the 14th century in quite some time, capable of restoring a consonant dimension to one of the great protagonists of 14th-century European painting.

The catalog, a considerable tome of almost five kilograms, while lacking an essay that gives the reader a concise overview, stands as a new updated monograph, which avails itself not only of the essays by the curators and some established art historians, but also of the contributions of a pool of very young scholars, all between thirty and thirty-five years of age, who deserve to be mentioned one by one, given also the consistency of the sections they curate: Alessandra Caffio, author of an essay on Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s lost frescoes for the façade of the hospital of Santa Maria della Scala (it is therefore necessary to reiterate how there was no more suitable place for the exhibition), Serena Calamai, co-author with Seidel of a long essay on Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s iconographic inventions, and again Marco M. Mascolo, who together with Alessandra Caffio authored the essay on Lorenzetti’s “civic painter” in the Sala dei Nove in the Palazzo Pubblico, Gina Lullo, who had the task of compiling the essay on the Maestà and the lost frescoes of Sant’Agostino, and finally Federica Siddi, with a contribution on the panel for the altar of San Crescenzio in Siena Cathedral. It is also necessary to add the names of other young people, between the ages of twenty-six and thirty-six, who, together with their colleagues just mentioned, dealt with some boards: Gianluca Amato, Federico Carlini, Marco Fagiani, Francesca Interguglielmi, Sabina Spannocchi, Ireneu Visa Guerrero. To the exhibition, therefore, the very high merit of having been able to focus on young people: an operation that, out of all rhetoric, can be said to be very successful, and gives the exhibition a fresh flavor, which makes it even more worthy of being visited.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.