by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 28/12/2016

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'Ai Weiwei - Free', in Florence, Palazzo Strozzi, from September 23, 2016 to January 22, 2017.

Is there, on the contemporary scene, an artist who, in terms of power, strength of message, vitality, originality, can somehow be compared to Michelangelo? It is a difficult question to answer, but if we had to express a shortlist of candidates, we would certainly include the name of Ai Weiwei (Beijing, 1957), to whom Palazzo Strozzi is dedicating, this year, its first Italian retrospective, entitled Libero. A title from which the leitmotif of the exhibition emerges with extreme clarity: the art of Ai Weiwei as a civil commitment, as a warning against all discrimination, as a powerful and (indeed) free outlet against censorship, with a narrative that unravels along the entire path of the exhibition going to touch, by necessity, on the artist’s stormy relations with the Chinese government and the instruments of repression. At the beginning of the year I interviewed Arturo Galansino, director of Palazzo Strozzi and curator of Libero, and asked him for anticipations about the exhibition: he promised a far-reaching, international event. I can say that the promise was kept.

It is just a pity that Reframe, the large installation specially conceived for the facade of Palazzo Strozzi that has entered, with all its disruptive vigor, into the canon of Ai Weiwei’s best works, has caused discussion to the point of making many forget that behind the inflatable boats that dialogue with the Palazzo’s windows there is a great artist endowed with an original personality, who has taken a coherent and never banal artistic path: a path that in Florence has been worthily narrated by Arturo Galansino. It is a pity because those who wasted their energies in belligerently bellowing against the facade installation overshadowed an engaging exhibition, extremely effective in terms of communication (aided in this by the art of Ai Weiwei himself, who among the most successful contemporary artists is certainly one of the least hostile for the general public) and which includes all the most interesting outcomes of the Chinese dissident’s production in recent years: in this context, Reframe constitutes but one stage, admittedly a fundamental one, but one that is linked to a broader discourse, one that starts from afar, one that tells us about an artist who is hated by the authorities, openly on the side of the weakest, capable of anticipating trends and being perfectly at ease among the tools that contemporary society offers him, Ai Weiwei being a blogger as well as a great and valid user of social networks.

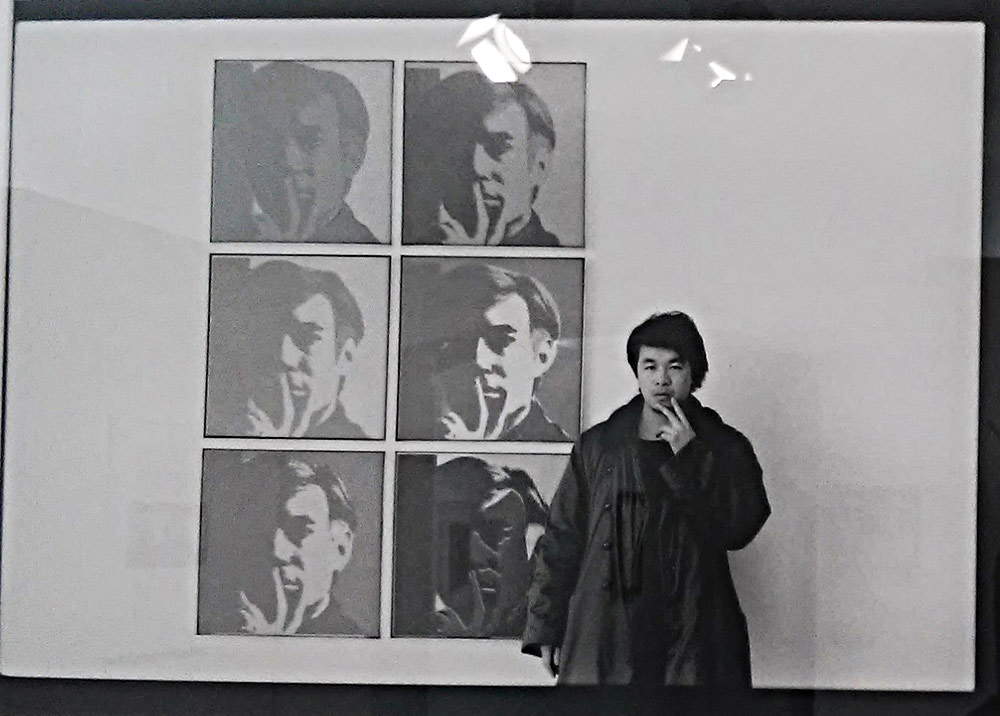

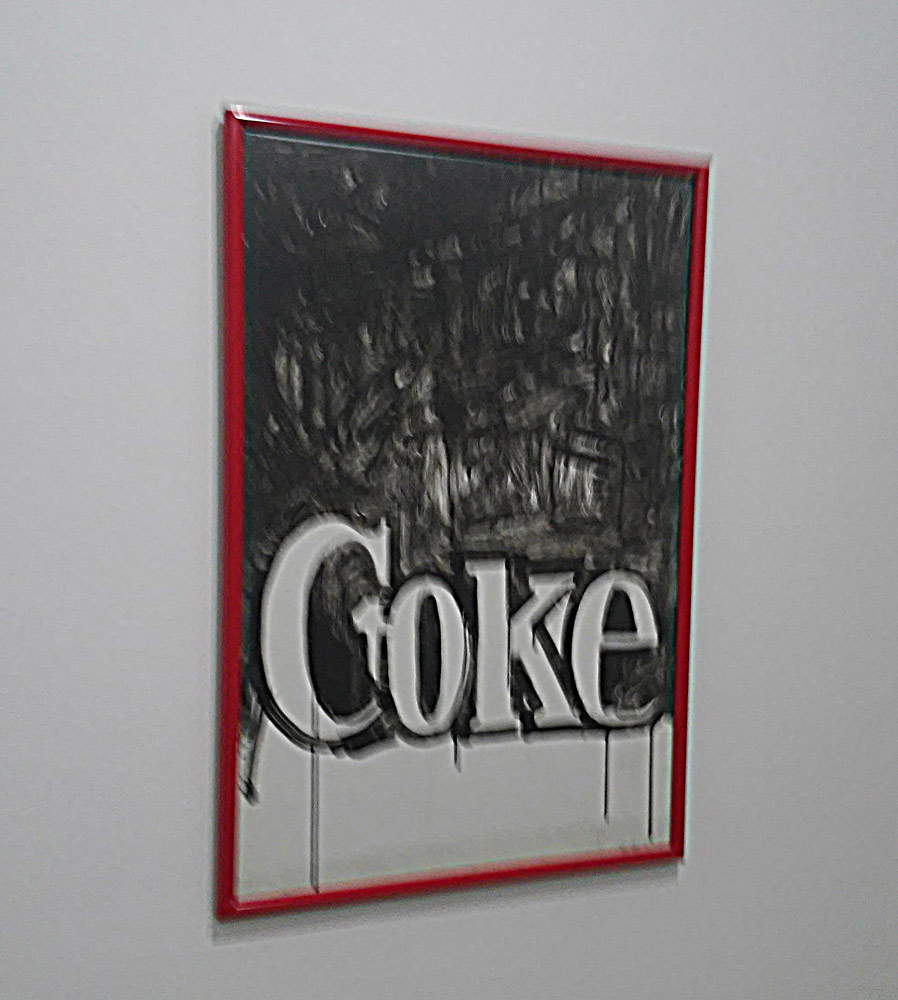

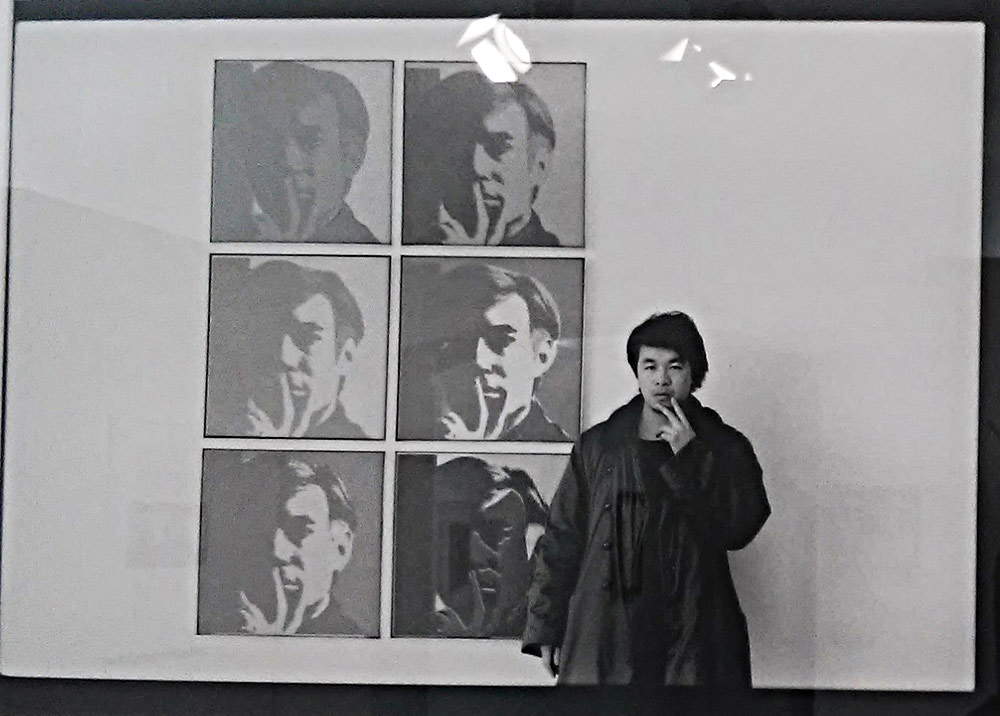

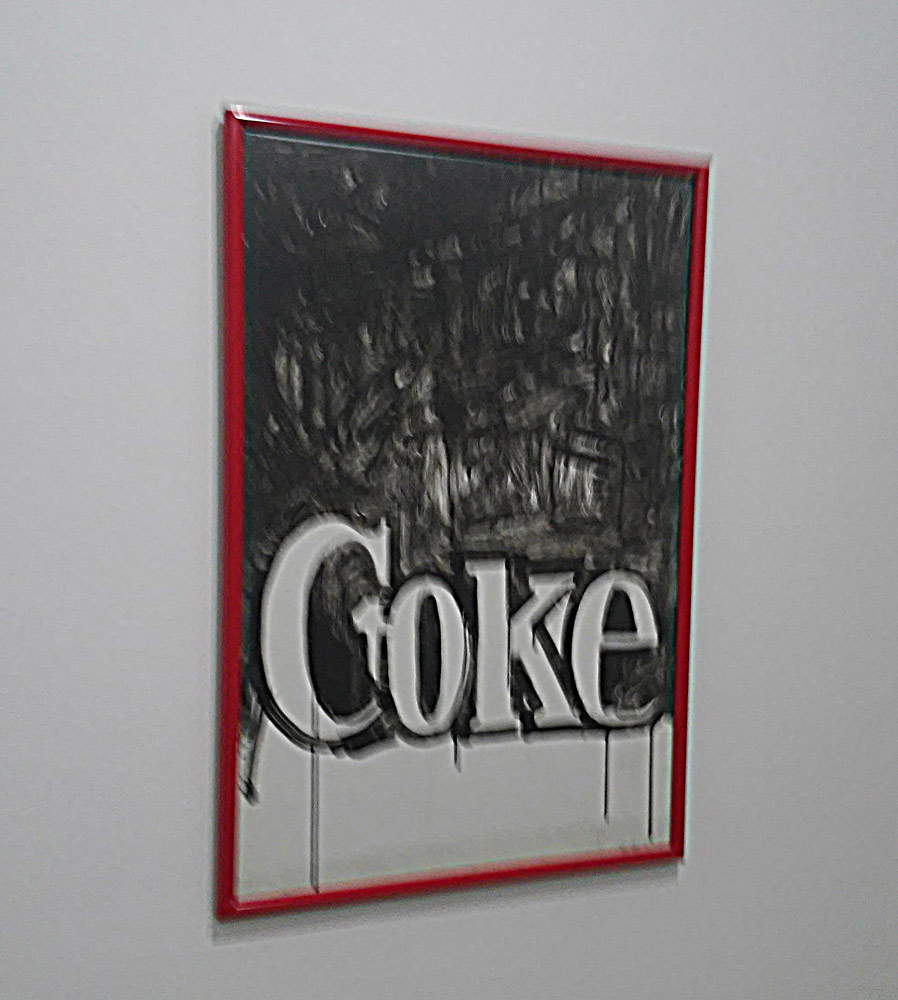

It is precisely for this reason that the visitor to Libero can perhaps benefit more by starting the visit from the rooms of the Strozzina rather than those on the main floor. For if one has not yet ascended, the underground rooms offer a vast overview that may well serve as an introduction to the works, many of them monumental in flavor, that fill the rooms on the upper level. The narrative, in fact, in room number thirteen of the exhibition (titled “New York”: in fact, each section bears a different name) begins in 1981, the year in which Ai Weiwei, son of a Chinese poet, Ai Qing, also a dissident like his son would be and subjected to long periods of exile and isolation, moved to New York with a handful of dollars in his pocket and a meager suitcase towering in the center of the room: Paying homage to Duchamp, one of the artists who most influenced him, so much so that he prompted him to dedicate a special work to him (a little man modeled with Duchamp’s profile), Ai Weiwei creates a ready-made entitled Suitcase for bachelors, through which the artist elevates the few things he had with him at the time of his relocation to the status of a work of art, making the difficulties he had to encounter upon his arrival in the United States (think only of the language barriers) very obvious. The thirty-seven photographs that paper the walls of the thirteenth room of the exhibition tell the story of Ai Weiwei’s New York years: there are not only the environments that the artist frequented (his home, his friends, the places where he spent his days) but also tributes to the artistic culture of the time. In particular, we see Ai Weiwei photographing himself together with a portrait of Andy Warhol (conceding a shot also to the caption that accompanied it at MoMA), but we also see a work, Coke, an ink drawing on paper, which is an obvious homage to the great pop artist and which also becomes a kind of prelude to many later works, those that investigate the relationship between contemporary society and tradition and of which we find some examples on the upper floor of Palazzo Strozzi.

|

| Ai Weiwei, Suitcase for bachelors (1987; suitcase, soap, toothpaste and toothbrush, 20 x 30 x 40 cm; Courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio) |

|

| Ai Weiwei photographs himself along with Andy Warhol’s self-portrait in the 1980s |

|

| Ai Weiwei, Coke (1982-1983; ink on paper, 91 x 63.5 cm; Courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio) |

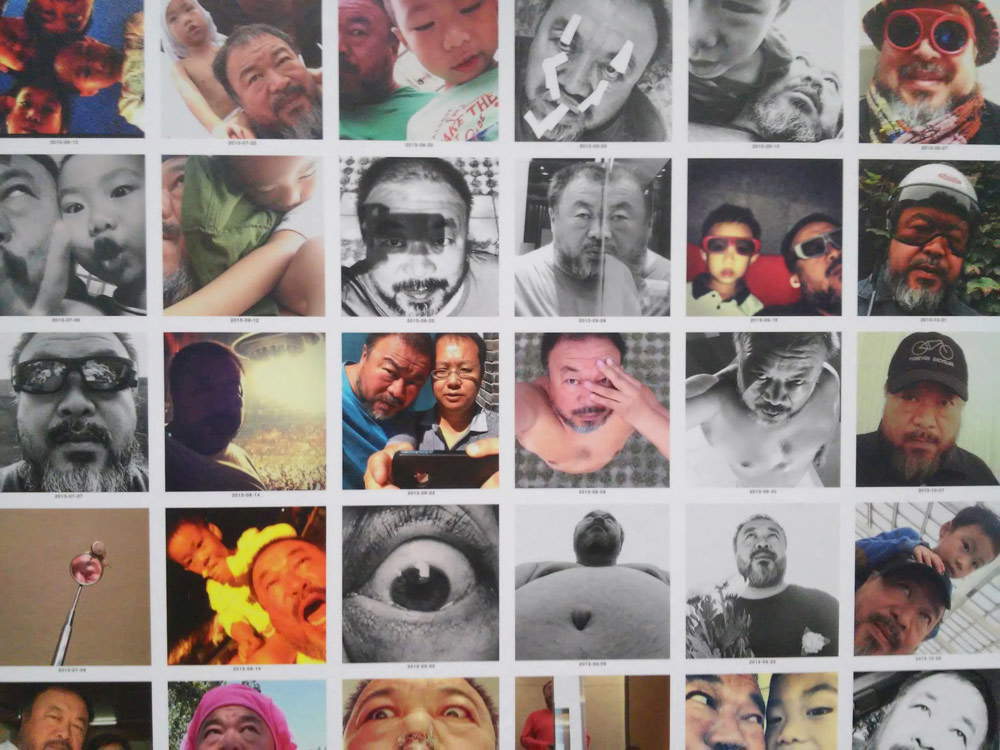

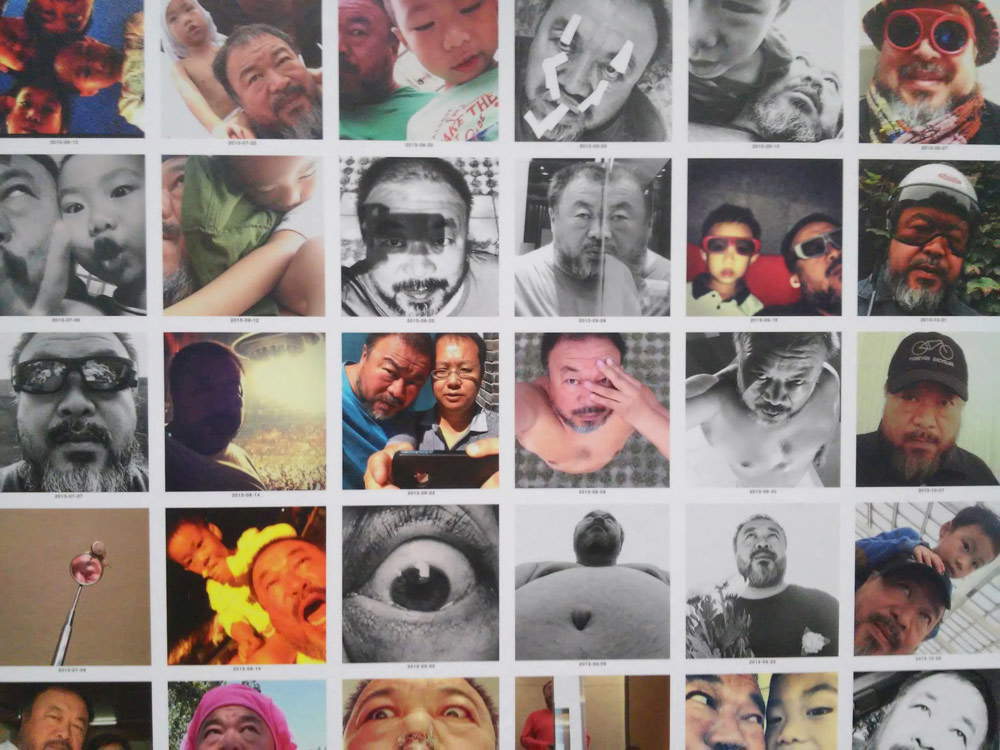

Through the 1990s, to which the fifteenth section is dedicated, entitled Beijing East Village (named after the community of artists that formed in Beijing in 1993, of which Ai Weiwei was an integral part, and which wanted to present itself as an alternative, albeit clandestine, to the cultural climate imposed by the communist regime), we come to the most recent developments in the Chinese artist’s career: the rooms of the Strozzina are covered with photographs that attest to the tight regime of surveillance to which Ai Weiwei has been subjected (the documentary Disturbing the peace tells in part why the Chinese government has paid and continues to pay special attention to the artist). These are images taken almost always by chance, with a cell phone, in the moments when the artist noticed that he was being followed by plainclothes officers who punctually end up in the photographs, often with expressions of surprise: testimonies as eloquent as the works of art that Ai Weiwei has dedicated precisely to the theme of surveillance (such as Surveillance Camera, a marble camera exhibited in two examples: one on the piano nobile, and the other at the Uffizi), and particularly effective in communicating that art and reality never travel on separate tracks. Also connected to the theme of repression is a work such as Taxi Window Crank from 2012 (crystal reproductions of cab window handles, an allusion to the regulations that, in 2011, required taxi drivers to remove window handles so that any demonstrators would be prevented from using them as improper weapons), placed at the head of a rapid succession that sees it followed by 2013’s Mask, a gas mask that emerges from a slab on the floor (a kind of denunciation of the pollution that grips China’s big cities), and 2016’s Tyres, a work that, despite its small size, strikes the viewer with force: they are reproductions of life jackets used by migrants to save themselves from the waters of the sea. Scenes that the artist witnessed in Greece, on the island of Lesbos, where he recently decided to open a studio: his closeness to migrants is much more concrete than one might think. Closing the “underground” itinerary are rooms dedicated to Ai Weiwei’s very latest “social activities”: Leg Gun is a tribute to all the social media users who have photographed themselves in the gesture of a leg held like a rifle, conceived by the artist as a protest against repression and which has gone viral, but it is also perhaps the most concrete proof of Ai Weiwei’s mastery of social media, while Selfie is a collection of self-shots that the artist has posted on social media from 2012 to the present.

|

| Ai Weiwei, Taxi Window Crank (2012; crystal, 3.6 x 11.5 x 4 cm; Continua Gallery, San Gimignano/Beijing/Les Moulins/Havana) |

|

| Ai Weiwei, Mask (2013; marble, 30 x 80 x 80 cm; Courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio) |

|

| Ai Weiwei, Tyres (2016; marble, 50 x 80 x 72 cm; Courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio) |

|

| Some photographs from the Leg Gun series (2014) |

|

| Some photographs from the Selfie series (2012-2016) |

|

| Ai Weiwei, Surveillance Camera with plinth (2015; marble, 117 x 52 x 52 cm; Courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio) |

Going up to the main floor, one encounters the installation Refraction, from 2014, consisting of a series of solar cookers that take the form of a wing, which, however, remains attached to the ground: it is still a symbol of the freedom to which the artist aspires, but which repression constantly and in every way tries to stop. The passage from Reframe to Refraction is one of the most intelligent in the entire exhibition: it is both introduction and summary, high praise to those who try by their own strength to win freedom, declaration of intent and effective presentation of the message that the artist wants to communicate not only to those who visit his exhibition, but to anyone who happens to pass by Piazza Strozzi(Refraction is located in the courtyard of the palace). Thus, by extension, to the entire world. But the two installations are also characterized by the sense of precariousness they suggest to those who observe them: the dinghies at the mercy of the waves of the sea, the solar kitchens gathered in a huddled wing, animated by a yearning for freedom as unstable and almost unrealistic as it is vague. But freedom necessarily passes throughuncertainty, and Ai Weiwei explained this concept well in an interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist, included in the exhibition catalog (in addition to this contribution, of note is a lengthy essay by Karen Smith devoted to the production, especially the recent one, of the protagonist of Libero, and a further interview done with Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson, who worked with Ai Weiwei on the Moon project): uncertainty is that of the migrant “willing to sacrifice everything he knows, what he knows, language, habits, memories, and relationships” in order to travel to a foreign (and perhaps hostile: he cannot know before he leaves) country, but it is also that which characterizes our time and "shakes the foundations of Western civilization and the so-called establishment."

|

| Ai Weiwei, Reframe (2016; PVC, polycarbonate, rubber, 650 x 325 x 75 cm each; Courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio) |

|

| Ai Weiwei, Refraction (2014; solar cookers, kettles, steel, 222.5 x 1256.5 x 510.6 cm; Courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio) |

The task of welcoming visitors to the part of the exhibition set up on the piano nobile of Palazzo Strozzi is left to Stacked, an installation from 2013 (but reimagined in a new layout specifically for Libero) that stacks a series of Forever brand bicycles (the only ones circulating in China during the artist’s childhood): the reference to the mobility problems affecting China is quite immediate, as is the reference to the famous Duchampian ready-made of the bicycle wheel, which, however, is better read and framed if one decides, as mentioned above, to visit the Strozzina’s rooms first. If Stacked amazes but also draws a smile, in the next room the dramatic Snake bag overwhelms us in all its tragedy: it is an installation made from school backpacks belonging to children who died during the 2008 earthquake in Sichuan province. Ai Weiwei’s is a strong indictment: the snake is one of China’s symbolic animals, and the message that leaks out from the work tells us about the failings of the regime, which is guilty of building schools out of shoddy materials, as well as covering up investigations into the tragedy. Ai Weiwei’s worst annoyances with the Chinese government came about as a result of an investigation into the earthquake in Sichuan province.Interesting, then, is the choice to cover the next room, Wood, with one of Ai Weiwei’s latest achievements, The Animal That Looks like a Llama but is Actually an Alpaca, from 2015. It is a white wallpaper with gold decorations whose protagonist is the Twitter bird intertwined with chains and surveillance cameras: the reference is to the period of detention the artist had to endure in 2011 (the alpaca was the protagonist of a meme widely used by activists on the web to protest government censorship).

|

| Ai Weiwei, Stacked (2012; bicycles, steel, rubber, 571 x 1214.7 x 733.9 cm; Continua Gallery, San Gimignano/Beijing/Les Moulins/Havana) |

|

| Detail of Stacked |

|

| Ai Weiwei, Snake bag (2008; 360 backpacks, 40 x 70 x 1700 cm; Courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio) |

|

| Ai Weiwei, The Animal That Looks Like a Llama but is Actually an Alpaca (2015; wallpaper; Courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio) |

Also in Wood, the exhibition introduces visitors to another of the fundamental themes of Ai Weiwei’s art: the reworking of tradition and its relationship to contemporary society. A work such as Grapes, a kind of cluster formed by a series of traditional wooden stools joined together, lends itself to multiple interpretations: it can allude to the strength that individuals can gain if they decide to come together, it can be a symbol of the radical transformation that Chinese society has undergone in recent years, but it can also be read as a tribute to the artist’s creative ability to take a mundane, familiar, everyday object and turn it into a work of art. If Map of China is a work with a vaguely romantic flavor (a large wooden map made up of several pieces joined together into a single entity: exactly like the various ethnic groups that populate the territory of China), so is, in the room named Jingdezhen (a large Chinese city known for its porcelain production), the wonderful little Free Speech Puzzle, where thirty-two porcelain tiles symbolizing the Chinese provinces form yet another map of China characterized by the motto “Freedom of Speech” inscribed on each of the thirty-two pieces, the works encountered in room nine, Vases, appear to us to be decidedly more radical and animated by an iconoclastic will to be interpreted, however, in a positive, almost nouveau réaliste sense. Han Dynasty Vases with Auto Paint and Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn are two of Ai Weiwei’s most famous, discussed, and controversial works: in the first case we have a series of vases dating back to the Han Dynasty (between the third century B.C. and the third century A.D.) that the artist has covered with coachbuilder’s paint, while the second is the celebrated performance, from 1995, during which the artist destroyed a Han urn dating back some two thousand years. Ai Weiwei is aware that there can be no future that does not take into account tradition, the cultural identity of a people, and historical memory: consequently, in these works, thedeliberate annihilation of tradition is a provocative method of affirming its enormous importance. Don’t know what you got til it’s gone, said a famous ballad from the 1980s: trivializing with some violence, the concept, from Man Ray to Ai Weiwei via the Cinderellas, is more or less the same, with all the nuances of the various cases and for all the situations to which it can be applied, but always somehow linked to a “negation-presence/absence-destruction” chain that cyclically chases itself.

|

|

|

| Ai Weiwei, Map of China (2013; wood tieli from destroyed Qing Dynasty temples, 55 x 195 x 195 cm; Courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio) |

|

| Ai Weiwei, Free speech puzzle |

|

| The works in the Vases room (foreground, Han Dynasty Vases with Auto Paint; behind, Lego brick reproductions of photographs from Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn) |

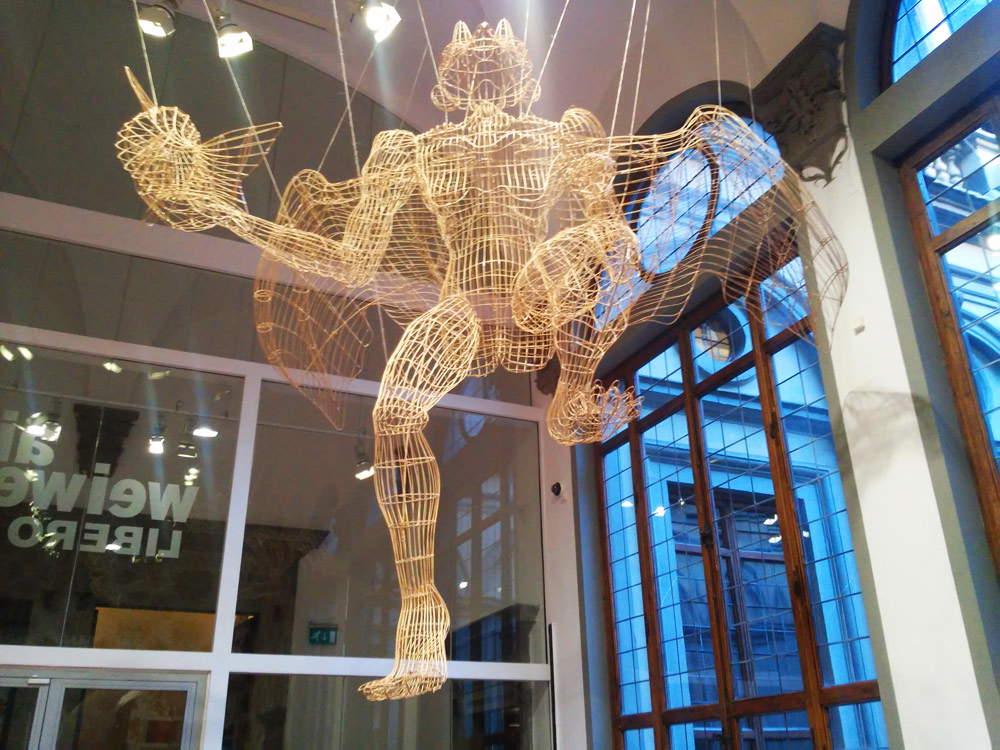

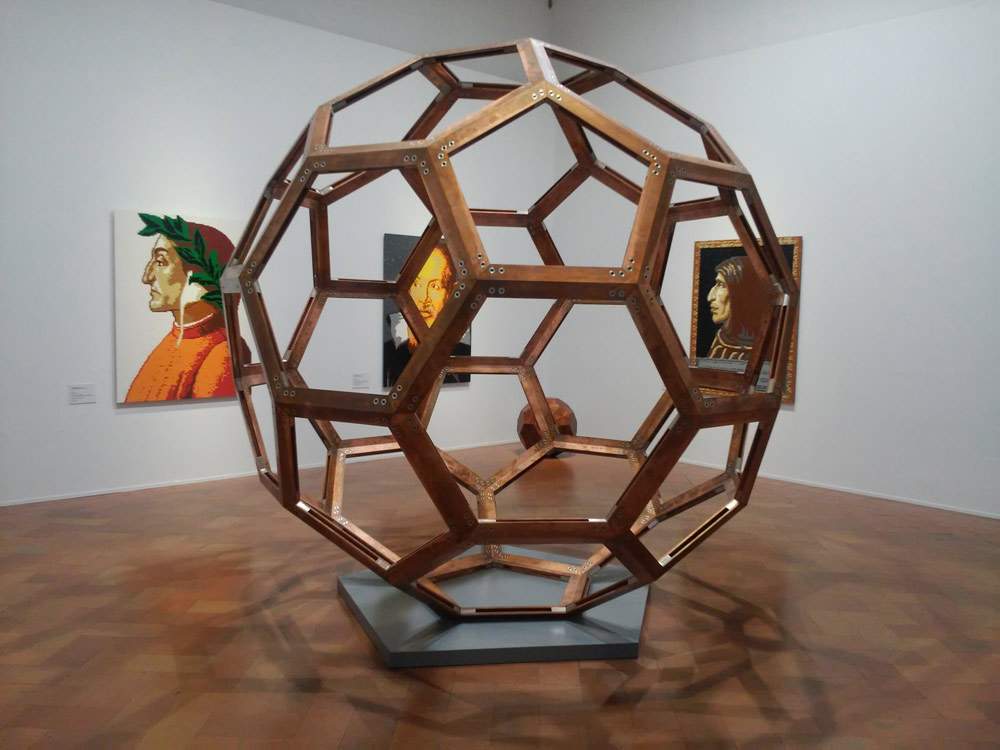

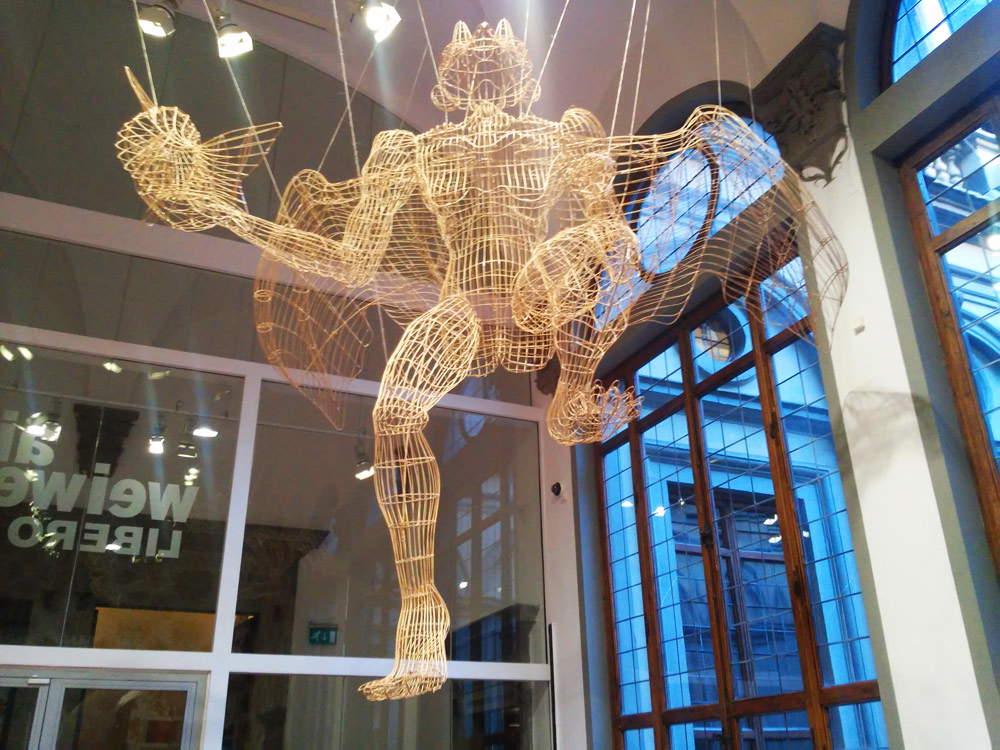

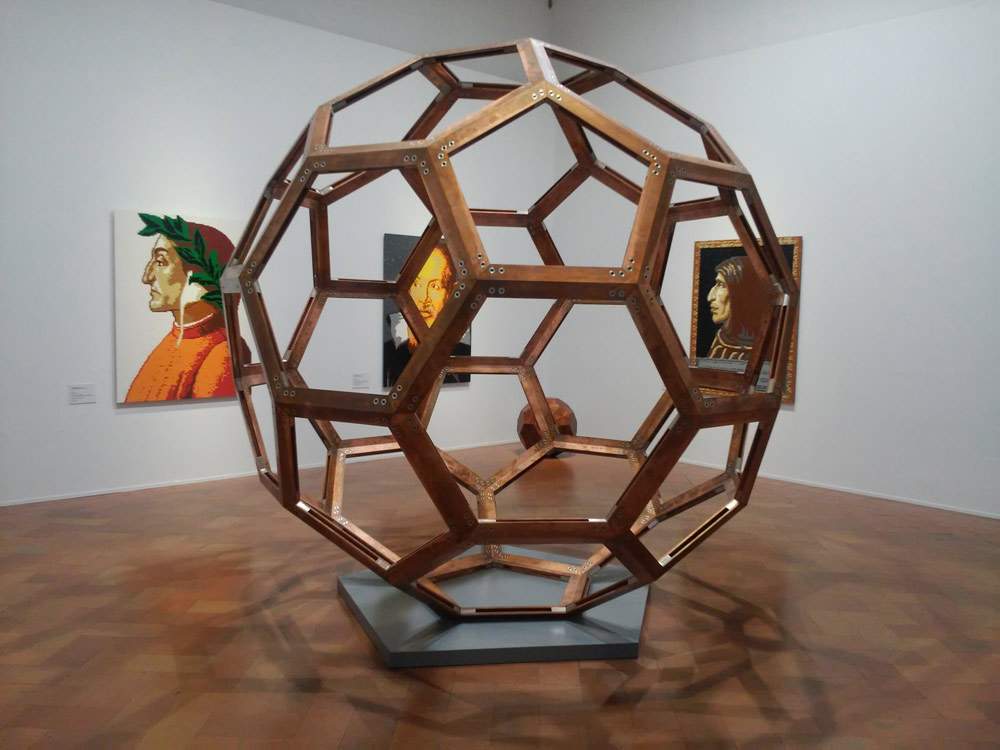

And that Ai Weiwei is an artist particularly attached to tradition is evident not only from his skillful use of traditional techniques (many ceramic and wood works can be found in the exhibition) but also from his continued inspiration from themes typical of Chinese culture and history: one room, Mythologies, features some splendid silk and bamboo sculptures(Taifeng, the “great wind,” Huantouguo, the bird man, and Feiyu, the flying fish) that, in addition to being made with traditional techniques, depict characters inspired by creatures from the Shan Hai Jing, “The Book of Mountains and Seas,” a geographic-mythological description of China whose origins date back some two thousand years. These fantastical figures hanging from the ceiling of the room not only show us Ai Weiwei’s keen interest in traditional Chinese culture: since the Shan Hai Jing was a book banned by the regime, they also become symbols of contestation, and it is no coincidence that they are included along with several photographs from the provocative Study of Perspective series. Their presence in the exhibition constitutes one of the simultaneously most interesting and exciting passages in the entire show. It’s just a pity we can’t see the full Zodiac Heads series, as happened in other Ai Weiwei exhibitions: we have to make do with the monkey, to remind us of the animal that represents the year 2016 in Chinese astrology. But it is nevertheless a particularly significant presence, because the Chinese attribute instability and unpredictability to the sign of the monkey: thatuncertainty mentioned in connection with Reframe and Refraction (but which never actually leaves the exhibition itinerary) returns openly. And if we talk about culture and tradition, we cannot fail to mention the homage that, in the exhibition, Ai Weiwei dedicates to Italy: in Renaissance we have Divina proportio and Untitled - Wooden ball, sculptures avowedly inspired by the illustrations Leonardo da Vinci made for Luca Pacioli’s De divina proportione, and above all we have the Lego brick portraits of four dissidents of the past (Dante, Galileo, Savonarola and Filippo Strozzi) that inevitably connect to the creeping motif of the entire exhibition. Again, a choice perfectly consistent with the meaning of Libero.

|

| Ai Weiwei, Feiyu (2015; bamboo and silk, 60 x 320 x 200 cm; Continua Gallery, San Gimignano/Beijing/Les Moulins/Havana) |

|

| Ai Weiwei, Huantouguo (2015; bamboo and silk, 250 x 400 x 170 cm; Continua Gallery, San Gimignano/Beijing/Les Moulins/Havana) |

|

| Ai Weiwei, Taifeng (2015; bamboo and silk, 200 x 170 x 86 cm; Continua Gallery, San Gimignano/Beijing/Les Moulins/Havana) |

|

| Ai Weiwei, Monkey (2011; bronze with gold patina, 69 x 33 x 38 cm; Faurschou Foundation, Beijing/Copenhagen) |

|

| The photograph from the Study of Perspective series “dedicated” to Palazzo Strozzi |

|

| The Renaissance room with Divina proportio in the foreground, behind Untitled - Wooden ball, and on the walls Lego brick portraits of Dante, Galileo and Savonarola |

The main floor itinerary closes with a further cry against censorship: He Xie (hundreds of small porcelain crabs, whose pronunciation in Chinese resembles that of the word “harmony,” a government slogan, thus turned upside down in an ironic key, and irony is an important stylistic feature of Ai Weiwei) and Souvenir from Shanghai recall the story of the artist’s studio razed by the Chinese authorities in early 2011. All that remains of the studio are a few shreds, rubble collected by Ai Weiwei and framed by the frame of a wooden bed, dating back to the Qing dynasty. Tradition, again, holds up the scraps of an uncertain present, and the visitor ends the exhibition with perhaps even more questions than he had at the beginning of his journey through Ai Weiwei’s art.

|

| Ai Weiwei, He Xie (2011; porcelain crabs of various sizes; Courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio) |

|

| Ai Weiwei, Souvenir from Shanghai (2012; concrete and brick rubble from the artist’s demolished studio in Shanghai, which includes a wooden frame, 260 x 380 x 170 cm; Courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio) |

But the answers, perhaps, must come from within. Or, at least, the artist’s intent is to prompt us to reflection, about ourselves and the world around us. Thus, each work is an invitation that follows along an unbroken thread that gathers around a few main themes: these are the main themes of Ai Weiwei’s art, which Arturo Galansino has excellently summarized in a review with few smears (a couple of examples: the Sex Toy, which appears in the Objects section and on which Galansino and Ludovica Sebregondi, curators of the exhibition texts, glissano, should have been better contextualized, and the same goes for the large Crystal Cube that seals somewhat awkwardly the room dedicated to Beijing East Village), which leaves full freedom to the visitor, and which obviously has the very high merit of making a city, Florence, often bent on itself and little capable of elaborating a high-level contemporary proposal, reflect on the contemporary. An exhibition that, it must be emphasized, silences those who think that Florence should bask in the glories of its glorious past without ever having to question itself. And finally, an exhibition that confronts (often almost brutally) the visitor with many of today’s dramas, that enriches and helps open our eyes to the world, making us aware right from the facade and courtyard of Palazzo Strozzi that, I quote again from the interview with Obrist, throughout history “we have never been so free, but at the same time this condition enchains us; because the freer we are, the more we realize we are in chains.” A kind of appeal to responsibility, to critical thinking, that appeals to our autonomy.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.