A unique journey through the history of photography. The Bachelot Collection on display in Rome

An art collection always has a unique narrative power: it tells the story, from the point of view of the person who put it together, and it tells about the collector, his passion, his taste, the life anecdotes that accompany each purchase. Thus it becomes a kind of self-portrait, or family portrait, as in the case of Mr. and Mrs. Florence and Damien Bachelot. Their collection is on display at Villa Medici, home of the Academy of France in Rome, a stone’s throw from Trinità dei Monti, until Jan. 15 with a discreet but capital-lettered title, COLLECTION, which represents well the dual soul of this collection: a family collection that is also an exceptional set of photographs.

It began as a corporate collection, that of Aforge Finance, created by Damien Bachelot and his associates. In 2009, during the financial crisis, Damien and his wife redeemed it so that it would not be dispersed, and since then they have enriched it with new prints and, in years when authors from large photo agencies did not have much attention on the market, managed to secure valuable pieces. “We never had a definite will to create a collection. For a long time we didn’t even have the awareness that we were building one,” declares Damien Bachelot. Yet today, his is one of the most important collections of photographic prints in France and a true synthesis of the history of photography with works by Henri Cartier-Bresson, Diane Arbus, Dorothea Lange, Vivian Maier, Paul Strand, Sabine Weiss-just to name the most known-which is offered here at Villa Medici in a selection of 150 images, curated by Sam Stourdzé, historian of the image, director of the French Academy in Rome, and who has led the Rencontres de la photographie d’Arles for years.

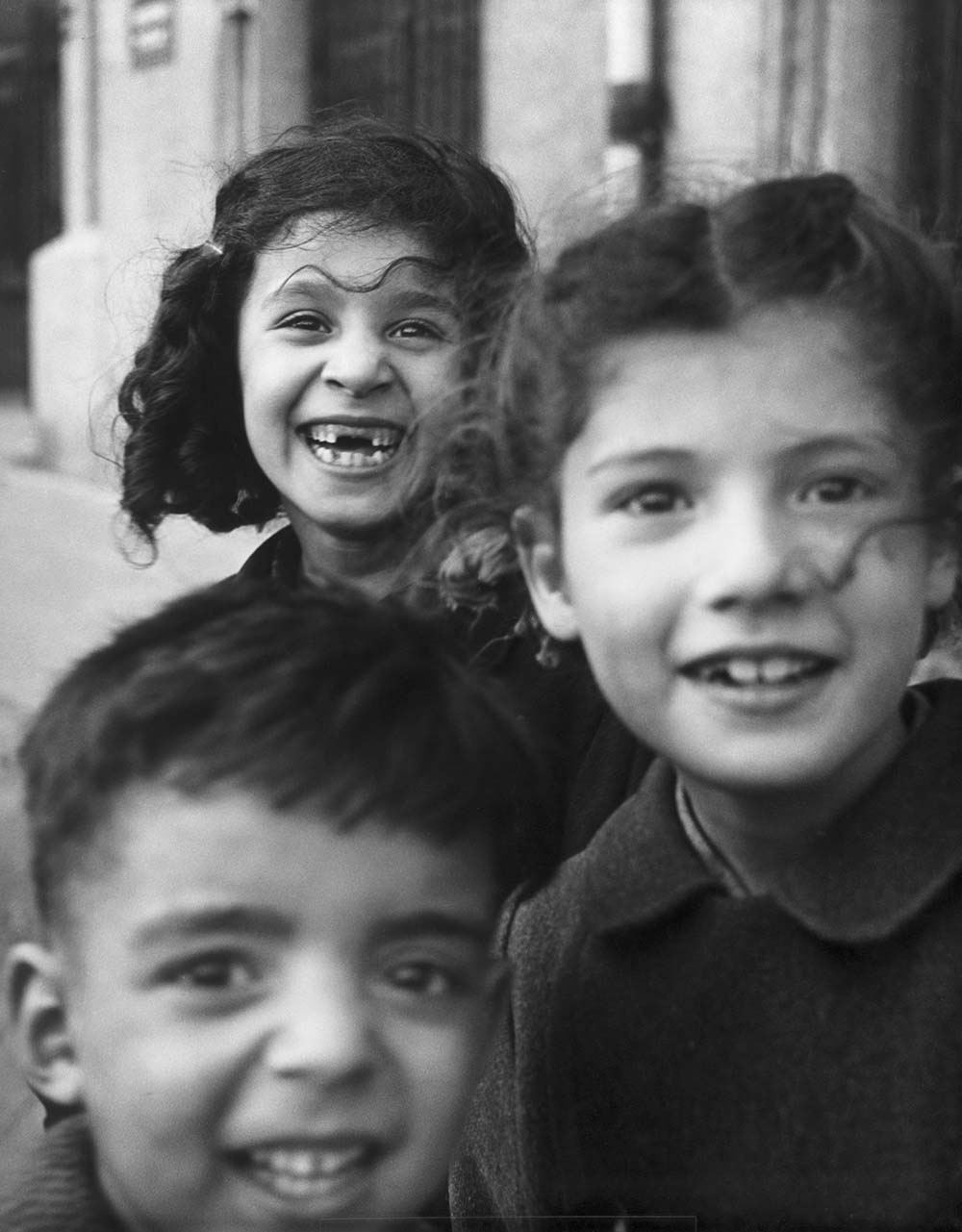

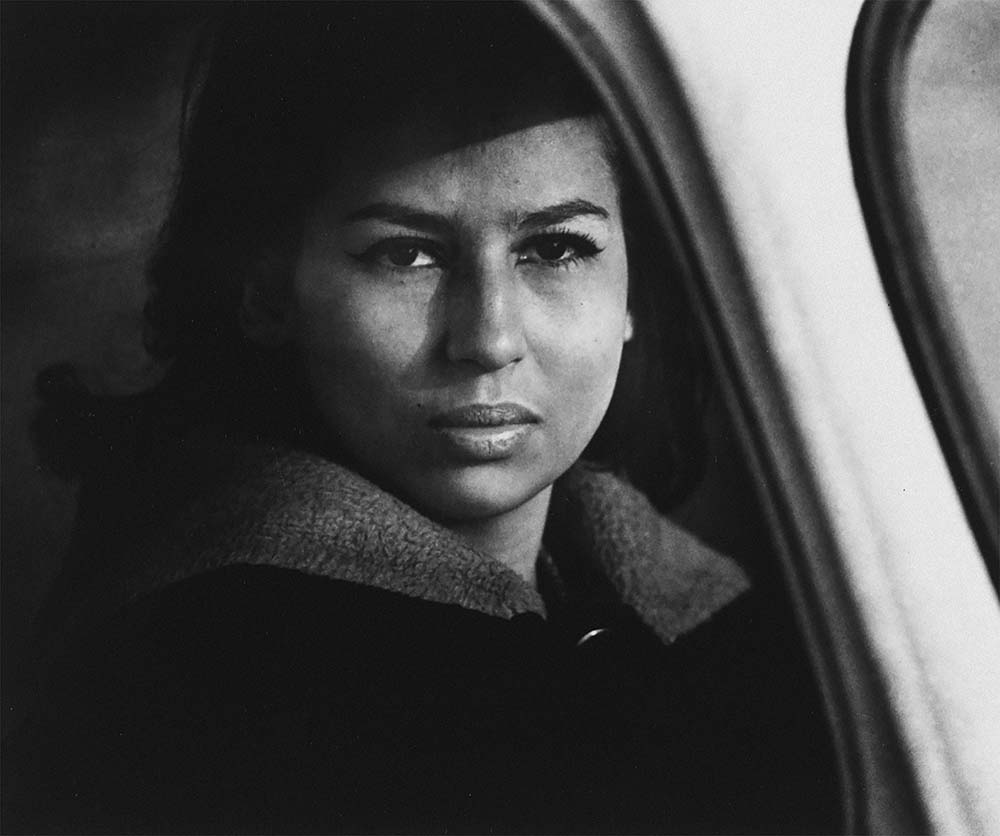

The original part of the collection focuses on humanist photography, which characterized postwar Europe and particularly France. The photographic gaze at that time is devoted to simple people and their daily lives and “corresponds perfectly to our deepest social and moral aspirations,” the Bachelots recount.

Paris is the center of this change: already from the beginning of the century it is a cosmopolitan city, and artists, and even photographers from all over Europe, arrive here. It is then that “photography becomes a democratic art and no longer just the pastime of the bourgeoisie,” writes Michele Poivert, photography historian and contributor to the exhibition. And that is when Henri Cartier-Bresson, who had left behind the Resistance and the experience of photographing the war, perfected his poetics of storytelling and gave rise, in fact, to modern photography. On display are some of his lesser-known works, such as The Bougival Dam (1955), one of his most original compositions.

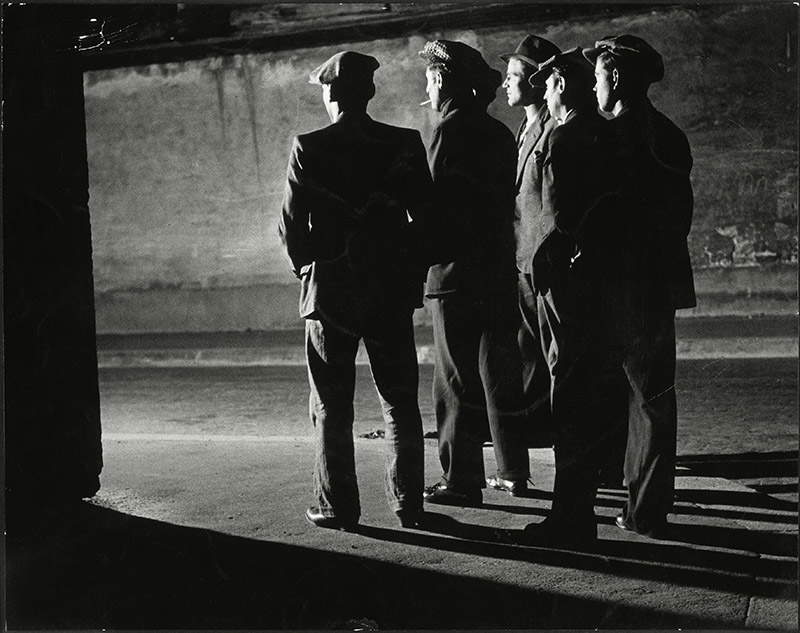

In the same period Robert Doisneau works with his irony made of details, as in Homme au tableau (1950), but also Brassaï, stage name of Gyula Halasz, whom Henry Miller had nicknamed “the eye of Paris” for his unique ability to capture the unknown sides of a city so photographed. And already at the time, photography was not just about men, as evidenced by the photos of Sabine Weiss, shown with Paris, enfants (1955) or Janine Niépce, art historian and member of the French Resistance, one of the first women in France to work as photojournalists. Her Marriage Seen from My Window, on the Louis Blériot Riverfront (1943) surprises with its contemporary gaze on an image that betrays its age.

In their adventure as collectors, the Bachelots often refer to the American market. There the demand for photographic works is less, and prices are more affordable than in France. It is there that they discover American Street Photography, and begin to acquire documentary classics from Dorothea Lange to Diane Arbus to Vivian Maier. The common trait is still the individual, in his human and social condition, but surely American photography reveals “a harsher, darker representation of human nature,” Sam Stourdzé points out. Striking in the exhibition The Defendant, Alameda County Courthouse, Calif . (1957) by Dorothea Lange, this man with his face hidden in his large, seemingly trembling hand, but also a simple and very painful portrait of Helen Levitt, Boy with gun (1942).

It was in New York that the Bachelots discovered Saul Leiter, a pioneer of color in the 1950s. A personal bond was born with him, late in his life when he was not yet very famous. This friendship is reflected in a series of prints in Cibachrome, “a lost process unparalleled for the depth of color,” says Damien Bachelot, displayed in the staircase that leads from the first floor to the last rooms of the exhibition.

We then come to the second part of the collection, which shows a greater focus on the contemporary and its experiments. And here, between the hardness of Josef Koudelka’s grays in his pictures of Eastern Europe, and Paul Fusco’s saturated-color American tales, there is also a bit of Italy, with the “pretini” of Giacomelli(Io non ho mani che mi accarezzino il volto - 1961/1963) exceptional extremes of black and white, and the pastel colors of Luigi Ghirri(Atelier Morandi, Grizzana - 1987). Then we come to contemporary reportage, with Luc Delahaye, Mohamed Bourouissa, Véronique Ellena, and then Laura Henno, who is striking in her artistic ability to recount the most difficult human conditions.

In short, it reads almost like a photography history textbook. One hundred years of shots of life, encapsulated in a simple and engaging display. It is a unique experience for the visitor, who rarely has occasion to be confronted with artistic objects such as these: vintage prints, yellowed over time, with ruined outlines, prints of all sizes that bring one closer to a physicality of photography to which large exhibitions have unaccustomed us. After all, attention to the authenticity of prints is proper to the collector. At a time when “the digital image reigns supreme and the photographic print has become unwieldy,” says Sam Storudzé, the works in this collection are instead physically unique.

Each object has its own story: there is a newspaper photograph that served as a reproduction for a magazine, a print presented at the Museum of Modern Art in New York for a particular exhibition, as evidenced by the label on the back, and a favorite print of a photograph that the author kept with him all his life(Lella by Edouard Boubat, 1948). It is a journey through photographic technique, starting with the silver salt print, characteristic of the 20th century, through various formats, from the 24x36 mm of the Leica to the 6x6 cm of the Rolliflex, Brassai’s favorite camera, and ending with Laura Henno’s video art, suggestively housed in the ancient cistern of Villa Medici.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.