Destroyed by illness and pain, rebellious in attitude, detached from the world and everyday life, an artist of the finest genius defeated by life. On February 8, 1943, Raphael Gambogi took leave of the world: alone, poor, desperate, ravaged by alcohol and an existence with few joys. For some twenty years he had forgotten about everyone, and everyone had forgotten about him. Of the circle of postmacchiaioli, who had formed in the wake of Giovanni Fattori’s lesson, Raffaello Gambogi was perhaps the least linear, and also the most unfortunate. And to think that, when he was a young man of only twenty-three, he had received a couple of excellent endorsements , we would say today: that of the master, Fattori precisely (although years later he would change his mind), who had been his teacher after Angelo Tommasi had initiated him into art, and that of Telemaco Signorini. It was 1897, and the year before Gambogi had participated in the Festa dell’arte e dei fiori, a great kermesse that offered artists the chance to display their work in an international exhibition, presenting Il riposo delle gabbrigiane, one of his best paintings, and gaining approval and appreciation. Then, at the risk of falling into cliché, a life worthy of being told in a film had begun for him.

First, the meeting with the Finnish painter Elin Danielson, thirteen years his senior: the two fell in love, married, and worked together, experimenting, opening up to each other in a kind of symbiosis that would radically alter the painting of both. Then, the difficulties of reconciling art with the practical necessities of existence: selling becomes difficult, a marital crisis ensues, Raphael and Elin move to Finland in an attempt to find each other again, perhaps they succeed, but the idyll is short-lived, because already in the woods of the north the first signs of a psychic discomfort take over, which later, upon their return to Italy, will result in a serious illness. Perhaps a serious form of depression, which forces Raffaello Gambogi to be admitted to the asylum in Volterra. Elin must care for her husband and take on all the duties of daily life; she will almost stop painting. Then, his death in 1919 is the fatal blow for Raphael: he will continue to produce, even writing highly original pages, but no longer as he once was, and above all almost isolated, locked in his grief. This is the story that is told by the exhibition Raphael Gambogi. Art as Revelation, curated by Giovanna Bacci di Capaci, which the “Giovanni Fattori” Civic Museum in Livorno is hosting until Feb. 25.

This is not the first time that Gambogi’s production has been made the subject of a dedicated exhibition: tracing for the first time a complete profile of his artistic story, after so many years of oblivion, was, in 2017, the exhibition Raffaello Gambogi. The Time of Impressionism, curated by Francesca Cagianelli at the Pinacoteca Comuanle in Collesalvetti. About forty works reconstruct a complete profile of Raffaello Gambogi: that of an artist who was born a Macchiaiolo, painting works that look to Fattori, after which he grew up a polite Impressionist who cloaked his paintings in a clear Nordic light, and ended his career with sharp, gestural, violent and original paintings that almost anticipate postwar research. The same path is the one that can be appreciated at the exhibition set up on the main floor of Villa Mimbelli, home of the Fattori Civic Museum.

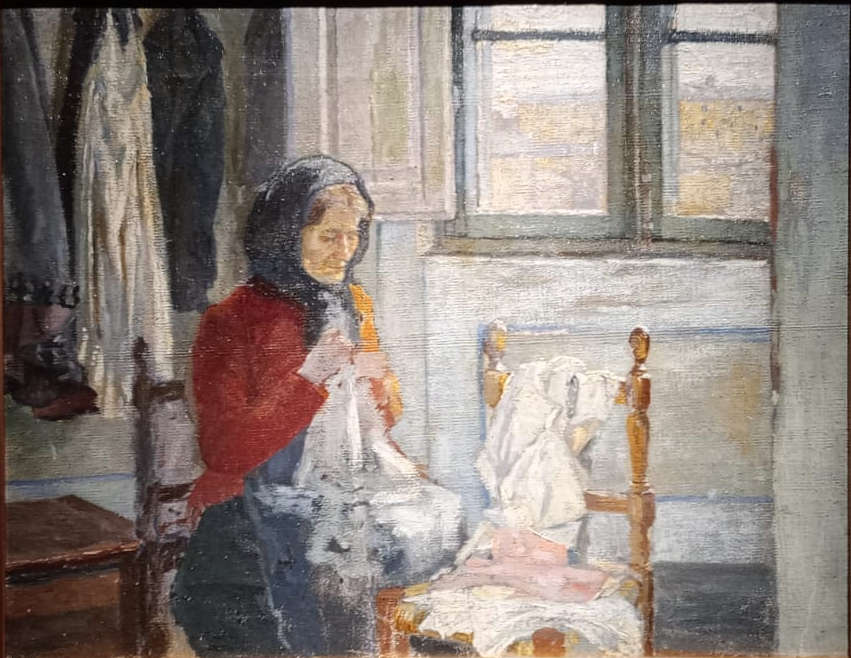

Gambogi, writes curator Bacci di Capaci, first reveals himself to be “particularly interested in the human figure, which is the happy protagonist of many of his youthful paintings.” These are the ones seen in the first room of the exhibition: Le fascinaie in Tombolo, with its overbearing backlight against a blazing sunset, already reveals a highly original personality, developing the lesson of master Angelo Tommasi toward a direction that already seems to anticipate the directions that Tuscan painting will take toward the end of the century in the wake of Nomellini and Grubicy, while the subsequent Ritratto della madre, of 1893, marks a momentary return to a more traditional, closer to the masters Tommasi and Fattori, and the same could be said for Courtyard in Banditella, which despite its humble subject matter, a chicken coop with chickens in the foreground, takes on an almost lyrical tone due to the glow on thehorizon, and demonstrates strong compositional qualities, with the sheaves in the background giving additional movement to the scene and prompting the eye to leave the chickens for a few moments in order to scan the landscape in the distance. The later Sosta(Rest of the Fields), also known as Riposo dei campi (Rest of the Fields), refers instead to the season in which Gambogi began to show off, literally, by participating in exhibitions: the intonation is similar to that of Il riposo delle gabbrigiane (The Rest of the Gabbrigians), with a peasant being portrayed during a moment of quiet, in a painting that hints at the Gambogi of later years. That is to say, a painter who would demonstrate a naturalist streak that would gradually begin to move away from the lesson of the masters and veer toward a delicate impressionism, and above all an interest in light that would become, in the turn of the years between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the preponderant element of his research. We can already sense the warnings of this in this painting: the figure of the peasant against the light, the rays of the sun striking his back and making his white back shine, the fine modulations on the profile of the mountains, the blond fields on the slopes of the heights that stand out in the heat of the summer light.

The “impressionist” Gambogi is the one with whom one becomes familiar in the next room, where a number of paintings resulting from fruitful exchanges with his wife Elin Danielson have been arranged. It is she who brings to Raphael’s painting the cold, delicate light of northern Europe, making her husband an original postmacchiaiolo who sees the landscape of the Livorno coast through his wife’s eyes, through the eyes of a Finn. The two of them, to use an effective image of Francesca Cagianelli, “must have constituted a rather anomalous phenomenon” within the cohort of painters who frequented Puccini’s Torre del Lago (Plinio Nomellini, Giorgio Kienerk, Ferruccio Pagni, and several others), because of their manner that mixed “Impressionist innovation” and “Nordic obsession” directed toward the Skagen School (and Peder Severin Krøyer in particular), which Elin must have known very well. Belonging to this period are paintings such as Pines by the Sea, Fisherman at Antignano, both from the early twentieth century, or the later Hot Hours of 1916, a summer painting about a bath on the Antignano shoreline, a beloved place and more than any other beloved: a woman, nude, walks out to sea, walking in the middle of the rocks, with the horizon fading into the white sunlight. More terse, on the other hand, are the paintings of the early 20th century, mindful of the crystalline light of the Danish painters they met through Elin, perhaps through magazines, or directly, either in Paris in 1900, when the artist stayed in France to join his wife who was participating in that year’s World’s Fair, or in Finland the following year, for their first stay in Elin’s homeland. They had met around 1895: she had come down to Italy for study reasons, they soon found each other, and in 1898, the decision to marry. “We are both happy and content, and are making thousands of plans for our life together in the future,” Elin wrote, shortly before the wedding, to a couple of friends in Finland.

Raphael Gambogi,

Raphael Gambogi, Raffaello Gambogi,

Raffaello Gambogi, Raffaello Gambogi

Raffaello Gambogi Raffaello Gambogi

Raffaello GambogiA room at Villa Mimbelli, moreover, has also been reserved for Elin’s works-a useful insert to allow a comparison with her husband and appreciate the results of the fruitful exchanges that took place between the two great artists, who painted together: it is curious to see a painting by Raphael, Il villino Benvenuti, in which is depicted Benvenuto Benvenuti’s house in which he and Elin lived for some time, and his wife’s Antignano alto , which is none other than the same street painted by her husband, but seen from the opposite side, as if she had set out to paint in front of him. And similarly interesting is the work Incontri, from 1901, where the signatures of Raphael and Elin appear together, probably because they both worked together on this painting that depicts three women, three friends, caught in a moment of happiness in front of the sea of Livorno. The visit then continues in the room dedicated to Raffaello Gambogi’s stay in Volterra: during the period of his hospitalization, art alone manages to give Raffaello a few moments of lightheartedness, a few moments of lightness, art alone seems to have a beneficial effect on him. Elin is aware of this, not least because the director of the frenocomio himself, Dr. Luigi Scabia, sees in painting a sort of antidote to the psychic malaise that had afflicted the artist: Elin, therefore, indulges him, lets him paint in peace, at the price of her being the one to give up art almost entirely in order to take care of the management of everyday affairs, as well as of her husband. Looking at Volterra’s paintings, it almost does not seem as if we are dealing with an artist who feels deep discomfort: on the contrary, Volterra’s works continue the serene and relaxed research that the artist conducted on the Livorno waterfront, showing a radiant city, with the full light of day investing the ancient monuments. It is the churches and buildings of the historic center that attract Gambogi’s attention: little room for the human figure, the artist finds flashes of happiness if he has the opportunity to focus on the landscape. Here, Gambogi’s research, Francesca Cagianelli has written, "seems to proceed in the direction of an emotional amplification of the view, between landscape-state of mind, urban folklore and architectural memories, where certain surprising luminous prodigies function as lyrical catalysts as much as an increasingly evocative, in terms not unlike those impressions conceived by Francesco Gioli on the wave of a kind of musical intuition, of which Matilde Bartolommei Gioli would later grasp ’the character of the fragment tuned to the feeling of color: ’musical seduction would say Baudelaire,’ to the point of judging his Mercato a Volterra not in terms of mere ’illustration of the place, but the result of assimilated impressions.’" When, on the other hand, human beings enter his painting, the tone changes: one of Gambogi’s masterpieces, Fra le pazze, a monumental, six-meter-wide depiction of the inmates of the Tuscan town’s asylum, unfortunately dismembered at an unspecified time and now known in its entirety only through old black-and-white photographs (a life-size reproduction was installed in the Volterra views room in the exhibition), is from the Volterra period. Only one part of it survives today, the central one, preserved at the Turku Museum of Art in Finland, which depicts a woman with her gaze lost in emptiness, cared for by a companion who looks at her somewhat detachedly as he holds her by the arm during a walk in the courtyard in an airy hour. Shown at the 1906 National Art Exhibition in Milan, the work caused a huge stir, but given its theme and especially given its size, it failed to find any buyers, not even among public institutions, the only people who might perhaps have bought a painting of those proportions. The following year, Elin sent the work to Finland with the hope of selling it in his native country, but without positive results: thus, traces of the work were lost, until the recent discovery of the central portion. It is likely that, in order to facilitate the sale of such a mammoth work, the decision was made to dismember it.

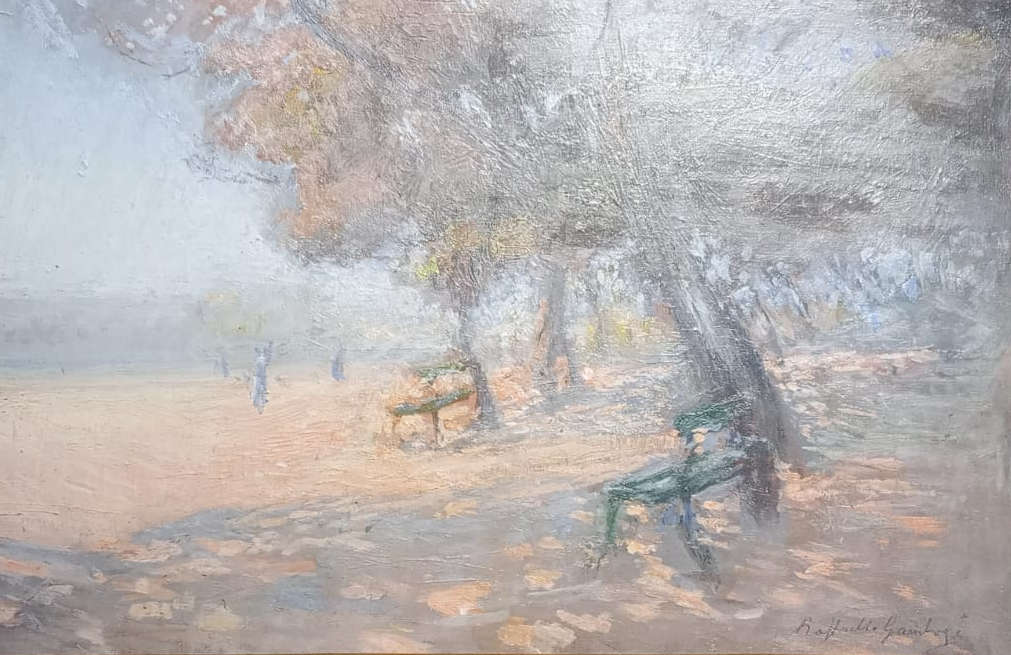

The conclusion, in the last room, is for works painted by Raphael Gambogi after Elin’s death, which occurred in 1919 from pneumonia. Even during the period of depression and hospitalization in Volterra, the artist had not, however, stopped hanging out with his friends: after the death of his wife, however, everything changes. Raphael withdrew into an increasingly mournful isolation (although there was no shortage of exhibitions, some of them even important ones), and his painting suffered from his torment, although the page the artist wrote in the last years of his life marks one of the most original peaks of his career, and this is demonstrated by paintings such as Costa livornese, Via della Bassata or Giardini all’Ardenza, all executed between the 1920s and 1930s. A portion of Gambogi’s career that would deserve new critical insights. The views here break up into coarse, undefined patches, which become increasingly uncertain as the years progress. There is no lack of a search for some effect of light, such as those that can be appreciated in Giardini all’Ardenza, with the sun filtering through the branches, producing luminous patches on the ground, under the foliage of the pines. The painting of these years, however, is decidedly instinctive, gestural; it almost seems as if Raphael paints on impulse, attacking the surface of the painting, sometimes even scratching it, as in Via della Bassata, where one can see, on the foliage of the trees, the characteristic lightning incisions that furrow, horizontally and diagonally, the patches of color with which the artist gives form to the elements of the view. There is no lack, however, even here, of a sense of light: it is enough to linger on the facade of the building to notice it. It is an art of supreme originality, which in some ways anticipates, of course quite unconsciously, the painting of the 1950s and 1960s. It is the product of a man overwhelmed by misfortune. A man who had nothing but his art.

Raffaello Gambogi,

Raffaello Gambogi, Raffaello Gambogi

Raffaello Gambogi Raffaello Gambogi

Raffaello Gambogi

Those who will not stop at the exhibition and decide to visit the entire Fattori Museum can go up one floor to admire Raffaello Gambogi’s most famous work, which is part of the permanent collection of theinstitute, Gli emigranti (The Emigrants), a work from around 1894 that ranks among the foremost and best of those recounting the drama of Italian migrants who, in the late 19th century, left the country to embark for America, often leaving from Livorno: farewells such as those the artist captures on his canvas, centering his attention on a few families saying goodbye (in contrast to master Angiolo Tommasi who, a couple of years later, would provide a less sentimental and more chronicle, we might say, of the migrants’ departure from the port of Livorno) offering to the eyes of the relative an elegiac and melancholic reading of emigration, lingering also on the suitcases, so many suitcases, that become a symbol of the baggage of hopes that the migrants carry with them to the New Continent. Seeing this work as well will provide an even more complete profile of Gambogi, who thus arrives to the public with an exhibition of certain interest, capable of continuing that path of rediscovery of the artist started seven years ago with the Collesalvetti exhibition, the first anthological exhibition ever dedicated to the Leghorn painter, compared to which the’current exhibition is smaller in size while maintaining the same layout and while lacking some important works that were instead present at the 2017 show (for example, the Hunter, of which the new exhibition displays a life-size reproduction, or The Morning of the Feast Day , which is nevertheless adequately accounted for in the catalog).

What emerges is a further, comprehensive portrait of the artist, painted by following the entire itinerary of his life and career, in the rooms of a museum whose visit allows one to further explore the context within which Raphael Gambogi’s art developed. These are the exhibitions one expects to see in Livorno. A worthwhile tribute on the 80th anniversary of his death to that “emotional and empathic painter” and “hypersensitive and restless man,” as Giovanna Bacci di Capaci defines him, who penned one of the most significant chapters in the art of his time.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.