by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 10/04/2018

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'Spain and Italy in Dialogue in Sixteenth-Century Europe,' in Florence, Uffizi Gallery (Aula Magliabechiana), Feb. 27-May 27, 2018.

In one of his seminal essays published in 1985, the great British scholar Michael Baxandall asserted that the problem of so-called “influence” is something of a curse for the art historian. It is a curse, argued Baxandall (the following translation is by the writer), because of his “erroneous grammatical bias about who is the agent and who is the patient [...]. If someone says that X influenced Y, he seems to be saying that X did something about Y, and not that Y did something towards X. But if we think about great works and great artists, the opposite is always true. And it is very strange that such an incongruous term plays such a fundamental role, because it goes in the opposite direction from the real strength of the lexicon. If we think of Y instead of X as the agent, the vocabulary is much richer is much more pleasingly diverse: draw on, resort to, make use of, appropriate, adapt, equivocate, refer to, take up, assume, relate to, have recourse to, react to, quote, differ from, assimilate from, align with, copy, address, paraphrase, absorb, make a variation from, bring back to life, continue, remodel, ape, emulate, imitate, parody, extract from, distort, deal with, resist, simplify, reconstitute, elaborate, develop, cope with, master, subvert, perpetuate, reduce, promote, respond to, transform, counteract... and you name it. And many of these relationships cannot be thought of in the terms of X having done something about Y, but in the contrary terms. To think in the abrupt terms of ’influences’ is to impoverish these differences.”

It was decided to start with Baxandall because the ground plowed by the great art historian more than 30 years ago (and still the terrain of contention today) is the one on which the exhibition Spain and Italy in Dialogue in Sixteenth-Century Europe was sown, staged at theAula Magliabechiana of the Uffizi Gallery until May 27 and curated by Marzia Faietti, Corinna T. Gallori and Tommaso Mozzati. Underlying the exhibition is the idea that in the 16th century, and to be exact in the period beginning with the Wars of Italy and continuing until at least the end of the age of Philip II of Spain (this is the time frame examined by the exhibition), the Mediterranean was the site of fruitful exchanges between Italy and Spain that took place not according to a unidirectional perspective (or that, at most, produced results that could be rigidly framed in compartmentalized schemes), but in a reciprocal, open and continuous manner. Consequently, a first problem is to ensure that the design of Spanish and Italian artists of the period, as well as those from anywhere else, is properly situated. It is worth remembering, moreover, that Spain and Italy in Dialogue is above all an exhibition of drawings, largely from the Uffizi’s nucleus of Spanish drawings, dating back to the donation, dated 1866, of Emilio Santarelli, the Florentine sculptor who left the museum thousands of sheets by artists of every place and era. Tackling these topics means, writes Marzia Faietti, “constantly broadening the horizons of research, coming close to the breaking point of the notion of school [...] without, however, renouncing the philological recovery of the artistic fabric of a specific place and the analysis of the transmission of knowledge in the different workshops.” Conscious, then, that modern art history can reconsider the concept of “national school” also in the light of the “revisiting of the notion of the nation-state taking place in the field of historiography” (Marzia Faietti continues by referring to Hobsbawm’s studies), it is possible to look at the themes of the Florentine review from a broader and deeper perspective.

A second, considerable problem consists in the circumscription of the adjective “Spanish” in reference to the works of Iberian Renaissance artists: an issue well pointed out, in his catalog essay, by Benito Navarrete Prieto, who questions whether it is not more correct to speak of “drawing in Spain” rather than “Spanish drawing.” The point is that in the sixteenth century, Navarrete Prieto points out, “in the different artistic workshops active in the Iberian Peninsula in the sixteenth century, we do not detect a real evolution nor any continuity of practices,” contrary to what would have happened in the seventeenth century, but not only that: the sixteenth century was a period of great transformations and radical changes in Spain. The crowns of Castile and Aragon were united de facto in 1479, but it was not until much later, with the move of the capital to Madrid, desired by Philip II, that a court was formed that could guarantee artistic homogeneity to the Spanish kingdom (and it still took a long time to achieve the goal, so much so that regionalisms and localisms are still clearly distinguishable throughout the course of the sixteenth century). Then add a couple of further pieces to shape an extremely composite picture: the strong presence of foreign artists, especially Italian and Flemish, and the sojourns that the Spanish artists themselves made in Italy, bringing back to the lands of their origins cues and suggestions.

|

| The exhibition Spain and Italy in Dialogue in Sixteenth-Century Europe. |

|

| The exhibition Spain and Italy in Dialogue in Sixteenth-Century Europe. |

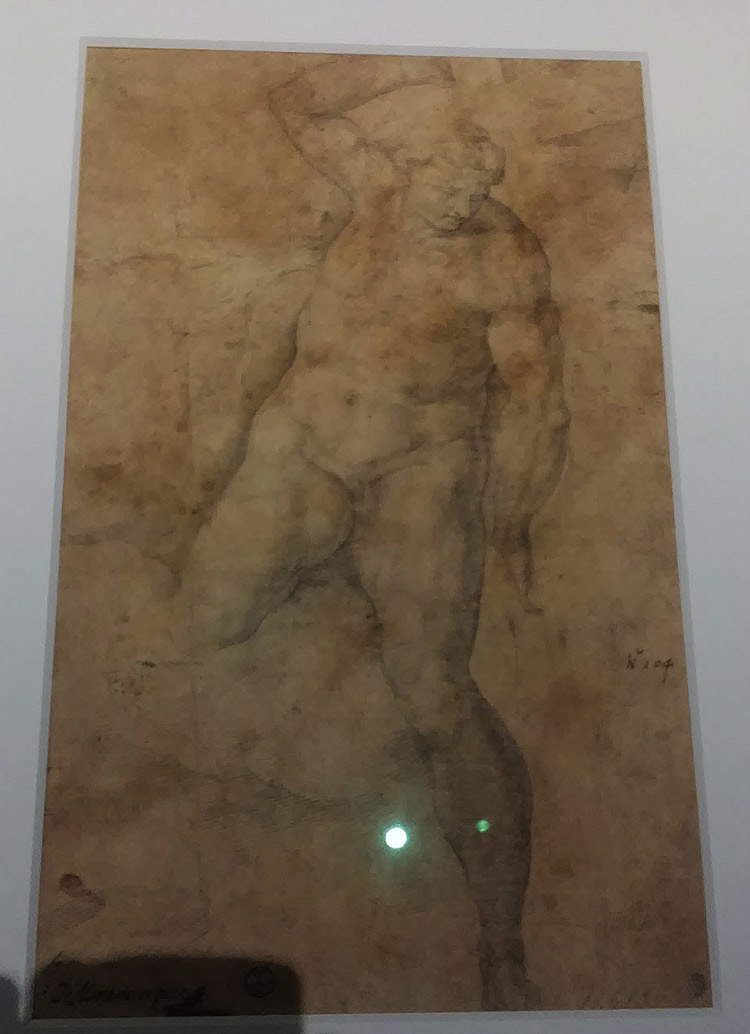

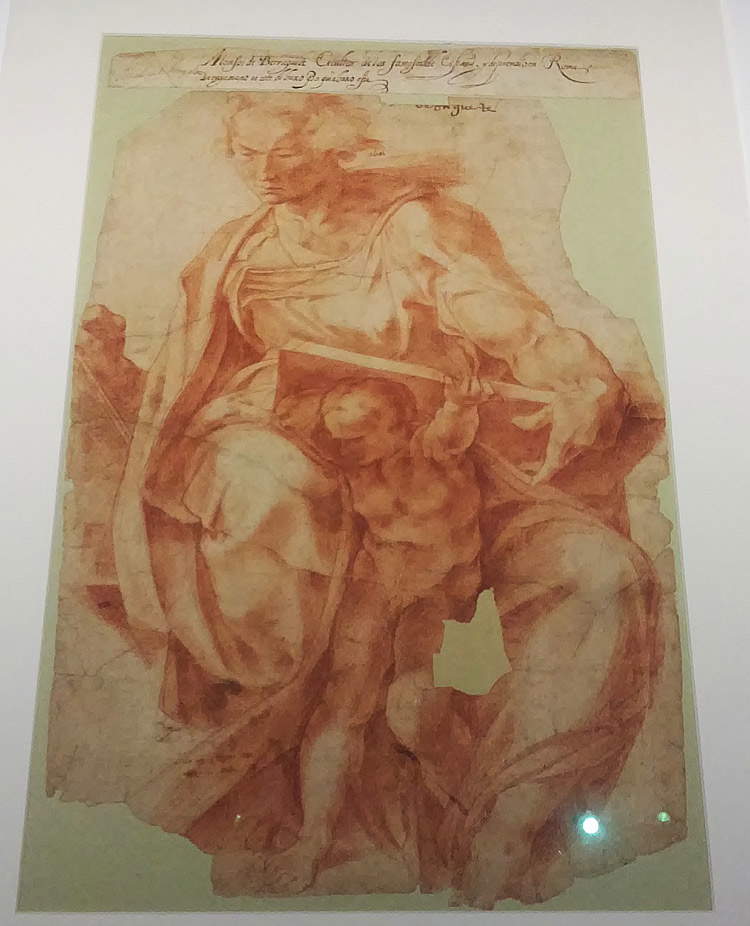

The exhibition, moreover, starts precisely from a trip to Italy: the one that Alonso Berruguete (Paredes de Nava, c. 1488 - Toledo, 1561), son of the great Pedro court painter in Federico da Montefeltro’s Urbino, made at a very young age, between 1506 and 1518, mainly in Florence, but without neglecting a parenthesis in Rome. The experiences he accumulated during his Tuscan sojourn found their zenith in the so-called Loeser Tondo, a work that combines a fascination for vigorous Michelangelo-esque figures (inferred from an impassioned study of Michelangelo’s Battle of Cascina ) with obvious Donatello suggestions, as attested by a sheet attributed to Berruguete (albeit dubiously) that copies Donatello’s Madonna of the Clouds: indeed, it could almost be said that the Loeser Tondo represents a sort of Mannerist actualization of Donatello’s anti-Classicism of the Madonna “of Verona,” placing itself, as Giuliano Briganti noted by developing a Longhi cue, “in clear anticipation of certain witch-like effects of Rosso.” Berruguete himself was one of the first (as well as one of the few) Spanish artists to use drawing as a means of fixing what he had learned from studying his great contemporaries, as evidenced by a copy of the Prophet Daniel from the Sistine Chapel (and note how the Castilian painter, as a great connoisseur of human anatomy, marks the muscles that can be glimpsed beneath the robes), and the same can be said of one of his contemporaries, of a later generation but equally animated by a desire to make extensive use of the graphic medium, Gaspar Becerra (Baeza, 1520 - Madrid, 1568), whose copy of Michelangelo’s Last Judgment Disma is on display in the exhibition.

Toward Rome turned the research of Pedro Machuca (Toledo, c. 1490 - Granada, 1550), who in his Madonna and Child, St. John and St. Joseph from the Národní Galerie in Prague, exhibited for the first time in Italy on this occasion, seems almost to want to combine Michelangelo’s energy with Raphaelesque grace “within a pictorial impasto made of broad, liquid brushstrokes , of bodies with a texture as soft as wax” (so Anna Bisceglia in the catalog), demonstrating that he has absorbed “the interweaving” that connotes, for example, the Madonna della seggiola, but also manifesting Mannerist impulses (the proposed reference is Domenico Beccafumi) for the restlessness of the characters, especially the Child who, with his difficult and contorted pose, seems to care nothing for his mother. Rome became the favorite city of Spanish painters passing through Italy from at least the mid-sixteenth century onward, and it is interesting to note, however, that Raphael and Michelangelo were not the only artists to whom painters arriving from the Iberian peninsula looked. The Florentine review well highlights the Spanish artists’ debts to Sebatiano del Piombo (Venice, c. 1485-Rome, 1547): his idealized devotion, which finds one of its peaks in the celebrated Pietà of Viterbo (a study for the deposed Christ, minimally scratched by the sufferings of the cross, is in the exhibition), inspired more than one young Iberian artist, as evidenced by the Christ Carrying the Cross from the workshop of Luis de Morales, derived from a prototype by the master, mindful of the suffering scenes of the Venetian painter, but devoted more to impressing the relative than to make him meditate, as certain details that Sebastiano del Piombo would never have imagined for one of his Christs suggest (the example of the rope around the neck, of a heaviness totally unknown to the art of the great Venetian, is worth mentioning).

|

| Alonso Berruguete, Madonna and Child known as the Loeser Tondo (1513-1514; oil on panel, diameter 83 cm; Florence, Palazzo Vecchio, Loeser Collection) |

|

| Alonso Berruguete (?), Madonna and Child, by Donatello (c. 1508-1510; red stone on paper, 364 x 268 mm; Florence, Uffizi Galleries, Drawings and Prints Cabinet) |

|

| Gaspar Becerra, Disma, by Michelangelo (before 1533; black stone on paper, 340 x 210 mm; Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe) |

|

| Alonso Berruguete (attributed), The Prophet Daniel, by Michelangelo (c. 1512-1517; red stone on paper, 399 x 281 mm; Valencia, Museo de Bellas Artes) |

|

| Pedro Machuca, Holy Family (c. 1520; oil on panel, diameter 72 cm; Prague, Národní Galerie) |

|

| Sebastiano del Piombo or circle, Christ Deposed (c. 1512; red stone on paper, 120 x 290 cm; Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe) |

|

| Workshop of Luis de Morales, Christ Carrying the Cross (c. 1550-1560; oil on panel, 59.5 x 56 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

The second part of Spain and Italy in Dialogue, corresponding to sections from the fourth to the sixth, deals instead with the reverse path, that of the artists who traveled from Italy (and often from other parts of Europe as well) to Spain. The fourth section, in particular, focuses on Spain as a center capable of attracting painters from abroad thanks mainly to the actions of Philip II who, as mentioned in the opening, after moving the capital from Toledo to Madrid, wanted to form a culturally and artistically advanced court around him. Not only that: the ascension to the throne of Philip II, who succeeded his father Charles V of Habsburg in 1556 following the latter’s abdication, entailed the beginning of a series of commissions that drew to Spain several artists attracted by the possibility of turning their careers around. Singular is the example of a painter like El Greco (real name Domínikos Theotokópoulos, Iraklion, 1541 - Toledo, 1614), an artist of never-to-be-forgotten Hellenic origins, “who seemed to assimilate the very essence of the places where he had spent his life and matured his knowledge, expressing it in an artistic language that could not be precisely localized in a particular country” (Marzia Faietti). On display is the Healing of the Blind Man Born commissioned by Farnese (thus preceding his move to Spain), which shows how El Greco had made Venetian figurative culture his own (notably the dynamism, flashes and spatial openings of Tintoretto), combining it, following a stay in Rome, with Michelangelo’s plasticism: these are the experiences he brought with him to Spain. There are no other works by Theotokópoulos in the exhibition, but it should be noted that El Greco’s Spanish graphic production is rather scanty and in poor condition, and that the addition of further paintings for a more comprehensive presentation of his artistic career presumably fell outside the objectives of the exhibition. However, in the catalog, Almudena Pérez de Tudela recalls how El Greco, in 1580, had been commissioned to create a work for one of the altars of the Escorial: the final result, however, did not please Philip II, with the consequence that the Cretan artist was no longer able to procure commissions as part of the prestigious undertaking that the sovereign had been undertaking for a few years.

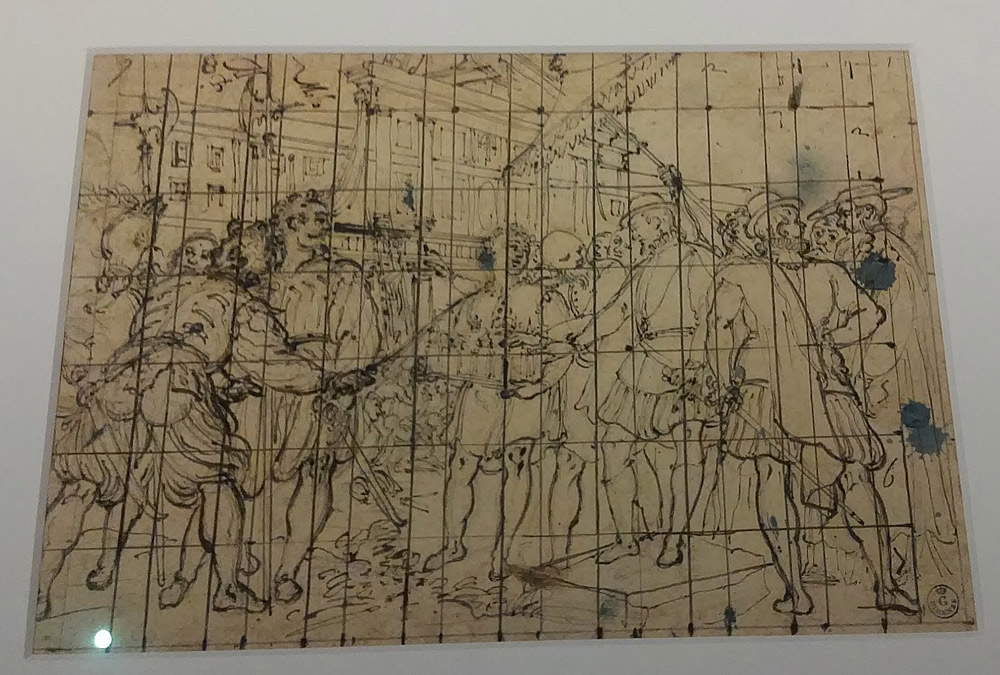

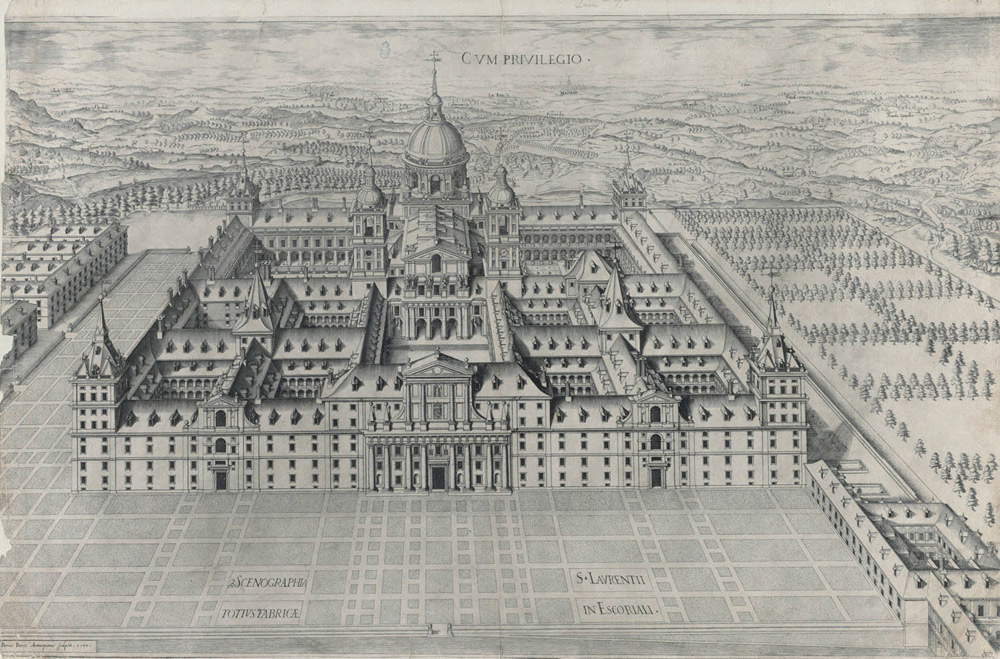

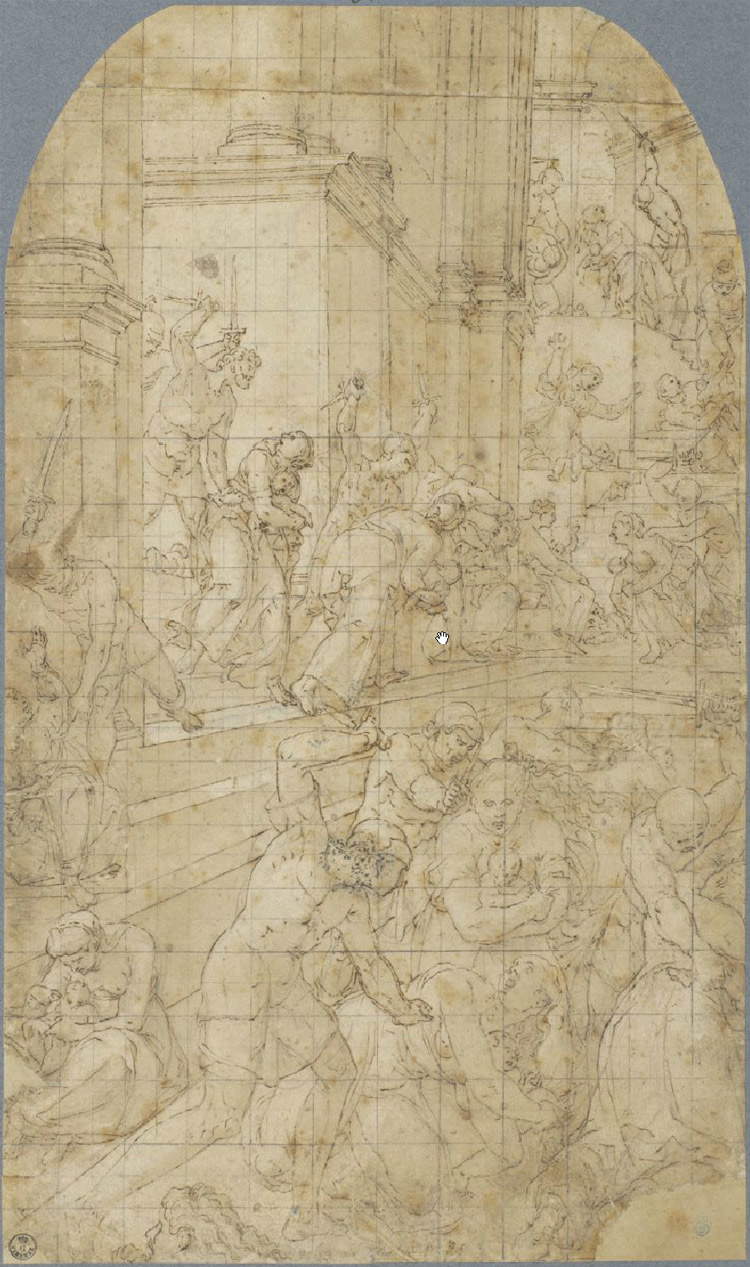

It was precisely the construction (and subsequent decoration) of the monastery of the Escorial that catalyzed energies from all over Europe and channeled great wits to Madrid. Following the first wave of Italian artists who plumped up Philip II’s court from the moment the young monarch ascended the Spanish throne (among them Pompeo Leoni, Romolo Cincinnato, Giampaolo Poggini), there was a second, far more substantial wave involved in the undertaking that started in 1563. It is necessary to emphasize that rather than the events that led to the construction of the imposing building destined to become not only a monastery but also the residence of Philip II and the burial place of Spanish rulers, the exhibition focuses on the role of drawing and printing in the Escorial adventure. On the one hand, drawing represented a way for Philip II to control the progress of the work. Indeed, it appears that the king had considerable expertise in architecture, and projects had to obtain his personal approval in order to be approved: in this sense, the preparatory sketch by Gregorio Pagani (Florence, 1556 - 1605) for the sets of the sovereign’s funeral apparatus, depicting Philip II approving the Escorial model, offers an interesting example. On the other hand, drawing was an effective means of fostering the circulation of ideas. Printing, on the other hand, was useful in spreading the fame of the enterprise, a goal to be achieved programmatically with engravings such as that by Pedro Perret (Antwerp, 1549? - Madrid, 1625) showing the general perspective of the entire San Lorenzo de El Escorial complex, based on a drawing by Juan de Herrera.

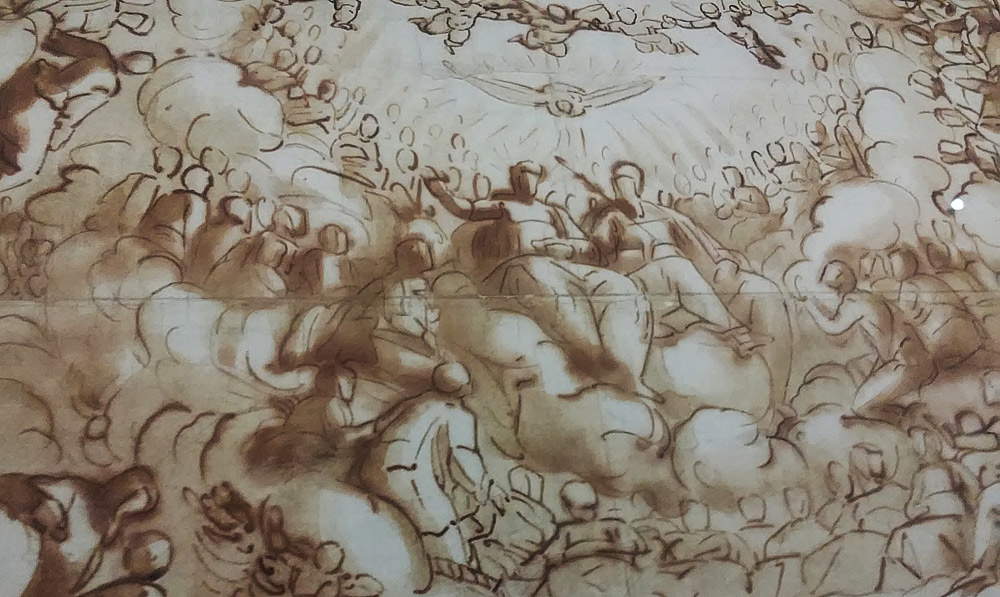

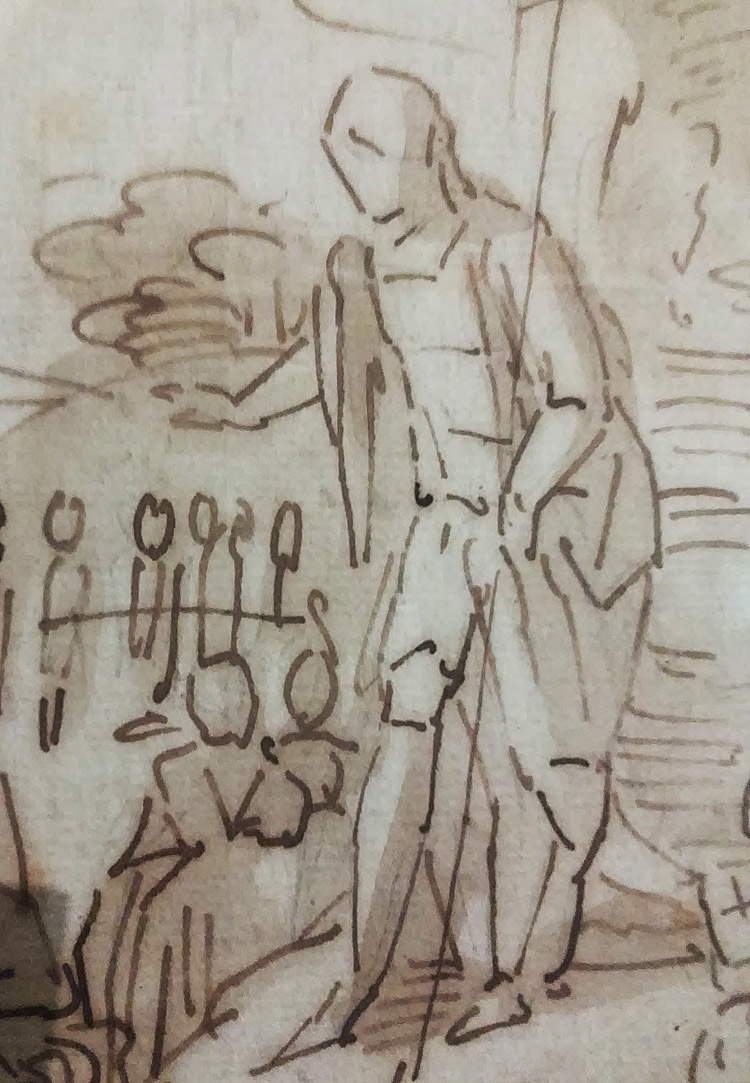

Italian artists participated mainly in the decorations. The most famous name is that of the great Luca Cambiaso (Moneglia, 1527 - El Escorial, 1585), who was called to Spain in 1583 and remained there for two years until his death: he was the first Italian summoned to the Escorial. His stereometric drawings are not to be missed, starting with that for the Glory of the Blessed (however, a copy is on display in the exhibition), the large fresco destined for the vault of the choir of the Escorial church, which the Florentine exhibition presents in its first version, the one that according to Raffaele Soprani was rejected by Philip II because the composition was contrary to the logic according to which “the saints of heaven did not stand in the same site [...] but that rewarded, according to their merits, they were distributed in various hierarchies, among which some were superior, and nobler, and inferior many others”: this motivation, “more pious than picturesque,” according to Soprani had the effect of destroying what he said was the most ingenious design ever to come out of Luca Cambiaso’s pen. Far removed from Cambiaso’s reduction to geometric forms was, on the other hand, his contemporary Pellegrino Tibaldi (Puria di Valsolda, 1527 - Milan, 1596), who even in his drawings did not fail to cloak his figures with the sense of monumentality that he derived from his long contact with the works of Michelangelo: moreover, his habit of structuring his compositions within architectures of a clearly classical stamp (for all these elements, observe the Strage degli Innocenti) was particularly consonant with the taste of Philip II’s court. His evidence was so successful that, after Luca Cambiaso’s death, he was the painter who took charge of much of the decoration of the complex.

|

| El Greco, Healing the Born Blind (c. 1570-1576; oil on canvas, 50 x 61 cm; Parma, National Gallery) |

|

| Gregorio Pagani, Philip II Approves the Design of the Escorial (1589; pen and ink, black stone, black stone squared repainted in stone and ink, black stone squared, paper, blue ink stains, 260 x 366 mm; Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe) |

|

| Pedro Perret, El Escorial, séptimo diseño, perspectiva general de todo el edificio on a drawing by Juan de Herrera (1587; burin, 562 x 857 mm; Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional de España) |

|

| Luca Cambiaso (copy from), Glory of the Blessed, detail (1584-1585, pen and ink, diliuted brush and ink, traces of black stone, paper, 495 x 412 mm; Palermo, Regional Gallery of Palazzo Abatellis) |

|

| Luca Cambiaso, Preaching of the Baptist (1583-1584; black stone, pen and ink, diluted brush and ink, paper, 346 x 199 mm; Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe) |

|

| Pellegrino Tibaldi, Massacre of the Innocents (c. 1587; black stone, pen and ink, brush and diluted ink, black stone squaring, paper, 402 x 237 mm; Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe) |

What, finally, were the consequences of all the exchanges seen so far? The answer lies in the last two sections of the exhibition. In the seventh, we review some of the artists who, in the wake of the results produced at the Escorial building site, began to update the artistic circles of Spain: the drawing of Luis de Velasco (Toledo?, c. 1530 - Toledo, 1606) with Fernando de Antequera in front of the Virgen de Gracia shows how well the artist assimilated the “practices used by the painters then active in the Escorial,” particularly in the conception of the scene “according to a continuous space that does not take into account the final division of the triptych, although the ordering of the masses clearly highlights its subdivided structure” (Roberto Alonso Moral). In fact, the work is the preparatory drawing for the Triptych of the Virgin of Graces in Toledo Cathedral, where in the central scene St. Anthony presents the infant Ferdinand of Antequera, later to become King Ferdinand I of Aragon in 1412, to the Virgin. The same can be said of Blas de Prado (Camarena, c. 1545-1546 - Madrid, 1599), whose loose and rapid stroke, like that of the Madonna and Child with Saints, is close to the drawings of Federico Zuccari (Sant’Angelo in Vado, 1539 Ancona, 1609): the artist from Marche went to the Escorial in 1585 and also stayed briefly in Toledo between 1586 and 1587, but there is also speculation that Blas de Prado traveled to Rome (and if it really occurred, the two may have met on that occasion).

Federico Zuccari’s legacy was also picked up by a naturalized Spanish Italian painter, Vicente Carducho (born Vincenzo Carducci, Florence, c. 1576 - Madrid, 1638), who came to Spain as a child, along with his brother Bartolomeo (also later hibernized into Bartolomé Carducho), who had followed Zuccari himself when he was called to the Escorial. The review concludes by presenting the visitor with the affairs of the Carducho family and those of another family of Italians who emigrated to Spain, the Cascese (or Cajés), namely Patricio Cajés (Arezzo, c. 1540 - Madrid, 1612) and his son Eugenio Cajés (Madrid, 1574 - 1634). Patricio and Bartolomé, painters with zuccaresca training, passed on their essentially Tuscan-Roman heritage to Vicente and Eugenio, who knew how to modify it, update it and use it to impart a remarkable development to the Madrid school. A substantial amount of Vicente’s drawings remain: particularly interesting is a sheet with Studî of angels, which is effective in suggesting the purposes of drawing according to the Italian-Spanish artist, who conceived it as a means of creating vast repertoires to be reused in later compositions and to provide models for the students in his workshop, who were used to copy and reproduce his drawings in order to progress in their mastery of artistic technique. Less “practical” is the only graphic example by Eugenio Cajés in the exhibition, a Visitation that, in contrast to what we observe in Carducho’s sheets, seekspainterly effect: clear evidence of how by now, at the end of the sixteenth century, drawing had become even in Spain a creative tool whose full potential was being explored, and how, for that reason, the sheets were carefully preserved.

|

| Luis de Velasco, Fernando de Antequera in front of the Virgen de Gracia (c. 1583-1584; pen and ink, diluted brush and ink, black stone, paper, 176 x 345 mm; Florence, Uffizi Galleries, Drawings and Prints Cabinet) |

|

| Blas de Prado, Madonna and Child (c. 1593-1599; pen and ink, black stone, paper, 100 x 80 mm; Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe) |

|

| Vicente Carducho, Studies of Angels (c. 1600-1606; pen and ink, paper, 186 x 149 mm; Florence, Uffizi Galleries, Cabinet of Drawings and Prints) |

The section on the Cajés and the Carduchos takes the form of a small exhibition within the exhibition that comes at the conclusion of a fascinating journey, but perhaps not for everyone, partly because the Uffizi exhibition tackles (with merit and quality) a field, that of relations between Italy and Spain in the Renaissance, which has recently begun to be explored in depth (a milestone was the exhibition Norma e capriccio, held in 2013 at the Uffizi) and which is therefore still far from the sensitivity of the general public, and partly because it is a review that is best approached if one starts with some knowledge, even basic, about the art of the time. It is not, in other words, an exhibition that concentrates its focus on popularization (and this is evident, for example, from the absence of captions to describe individual works, or from the idea of not using as many panels as there are sections, but of grouping information into individual panels that serve several portions of the exhibition), although the introduction and conclusion videos provide valuable support to the visitor: in the one the audience finds at the beginning of the itinerary, views of the Mediterranean restore with immediacy the idea of exchange and travel by immersing visitors in the full scope of the themes addressed by Spain and Italy in Dialogue, while the concluding film shows some of the works that have arisen from the preparatory drawings on display.

Spain and Italy in Dialogue focuses on its aspect as a research exhibition: a research that, in the curators’ intentions, also invests some important methodological aspects such as, quoting curator Marzia Faietti again, “the opportunity to conceive open catalogs” that aim to overcome orderings too rigidly set on regionalist schemes or on the concepts of national school (“consequences of specific historical moments and not criteria endowed with universal validity”), and again the opening of the museum to a “global circulation of culture” in line consistent “with the uninterrupted exchanges between European and non-European countries favored by historical, economic and exocial vicissitudes,” the construction of a broader perspective around an author or an artistic context. In other words, the fine-tuning of a new artistic geography: this seems to suggest between the lines a review that therefore not only achieves, effectively and with the quality guaranteed by a solid scientific framework, the objective of developing a thorough investigation of the Spanish folios preserved in the Uffizi, of contextualizing the practice of drawing in sixteenth-century Spain (and in this sense the catalog becomes a valuable tool: note how descriptions are lacking in the worksheets, although detailed descriptions exist for many drawings on the Euploos project website) and to outline the developments of the arts in the same area and the dialogues that came into being in those years, but it insists on pointing out a precise path for art-historical research. And in this respect it can certainly be said that Spain and Italy in Dialogue is animated by a modern and forward-looking vision. A further note of merit, finally, for the layout, which has allowed theAula Magliabechiana to free itself for the first time from the dividing panels and temporary walls that had occupied it in previous exhibitions, thus offering the public an open space that is also more congruous with the very name of the exhibition venue.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.