A long, repetitive immersion in Munch's anguish. What the Milan exhibition looks like

It is true that Edvard Munch is one of the most anguished artists ever: he himself claimed that his suffering, anxiety and illness were so much a part of himself and his art that their destruction would also destroy his art, but from the exhibition that Milan’s Palazzo Reale is dedicating to him until January 26, 2025 on the80th anniversary of his death you will probably come out depressed and with a sense of cosmic pessimism if you already tend at times to get caught up in anxiety and restlessness. The chosen title, Edvard Munch. The Inner Cry, already alerts you to the character of the exhibition, but more importantly it serves as a direct reference to theNorwegian artist’s most famous, most significant and most reinterpreted work, The Scream, which you will only see in lithograph form in the exhibition. So if you plan to visit the Milan exhibition to get a closer look at that human figure with a skull-like face, dressed in black, bringing his hands to his ears as he opens his eyes and mouth wide to let out a sonorous cry of despair, a cry that apparently is of only one individual but may represent the cry of all because universal are the feelings of loneliness, anguish and the torments of death, and that fiery, sinuous sky that follows the lines of the landscape, deformed like those of the human figure itself, no, know that you will not see it: neither the tempera painting nor the pastel of The Scream from the collection of the Munchmuseet in Oslo, the museum from which all the works in the exhibition come, arrived in Milan for the occasion; there is only a black-and-white lithograph from 1895.

There is also to be considered that the intent of the exhibition, as stated in one of the prefaces of the catalog, is “to return a more articulate view of Munch that broadens, starting from the necessary psychic biography of the artist, our vision and understanding” of the artist himself; “to broaden the field of investigation to understand, on the one hand, how Munch fits into the evolutionary process of the history of’art and, on the other hand, how artistic-literary manifestations, philosophical speculations coeval with him, in short, his culture affected his art” and to highlight how, beyond personal experience, Munch’s works are framed in the socio-culturalhumus of Nordic matrix. In the exhibition, these intentions are actually concretized in long panels to read (get ready because there will be many of them, written with the support of Costantino D’Orazio) and in the display of a few of the Norwegian’s works depicting the bohemian circlemien of Kristiania (present-day Oslo), a group, in which Munch also joins, of Norwegian intellectuals who fought against restrictive middle-class values, gender and class prejudices, and against constituted power, and in the presence of the portrait to Stanisław Przybyszewski, a Polish writer with whom Munch came into contact in Berlin in the literary circle of Swedish playwright and writer Johan August Strindberg. It was in this context that Munch found himself sharing with other intellectuals reflections around existentialist philosophers such as Kierkegaard, Schopenhauer, and Nietzsche, under the influence of a pessimistic symbolism that hinged the ideas of the circle, as well as ideas about the mechanisms of the unconscious. It would have been useful, in my opinion, to propose comparisons or written documents to bring about a more concrete and direct understanding of that link between Munch’s art and the Nordic cultural context.

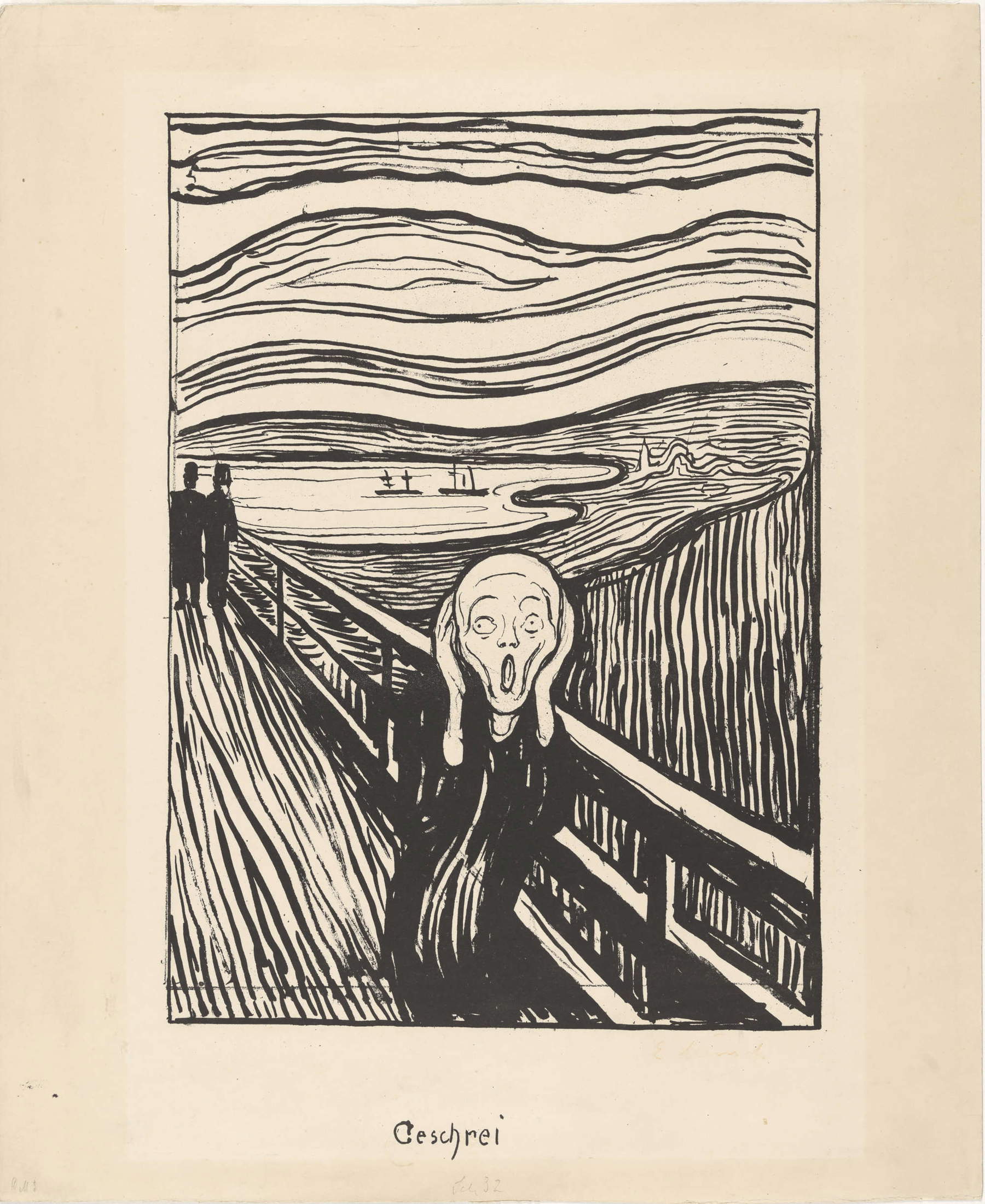

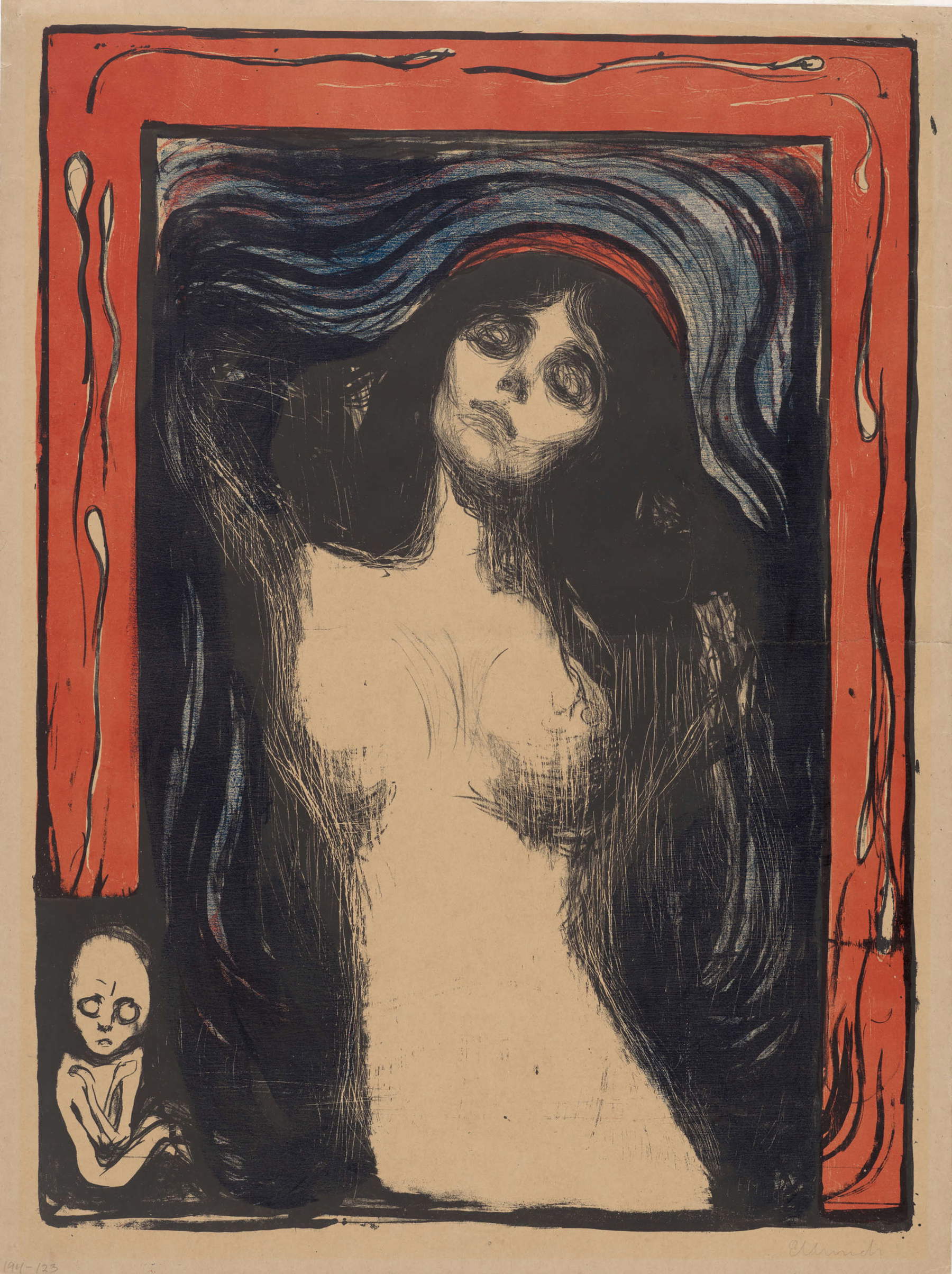

As mentioned, all the works on display come from the Munchmuseet in Oslo, so the Milan exhibition is nevertheless a good opportunity to see live paintings that are not kept just around the corner and that we would be unlikely to come across in Italian exhibitions (it has been ten years since the last major exhibition in Italy of works from the Munchmuseet’s collection was held at the Palazzo Ducale in Genoa, Ga, while forty have passed since the exhibition dedicated to the Norwegian artist that was held at the Palazzo Reale in Milan and at Palazzo Bagatti Valsecchi between 1985 and 1986, for which The Girls on the Bridge, the work that closes the current Milan exhibition, was chosen as the guiding image). Although, as already anticipated, The Scream is present only in black-and-white lithographs, there is nevertheless no shortage of masterpieces such asSelf-Portrait, Melancholy, Despair, The Kiss, Vampire, The Death of Marat, Self-Portrait Between Bed and Clock, Starry Night and The Girls on the Bridge. And some works are presented repeated in different versions and with different techniques to highlight how Munch used to elaborate on the same motifs over the years and throughout his production. Examples are The Sick Child (etching, 1894, and color printed lithograph, 1896), On the Deathbed. Fever (pastel, 1893) and Struggle Against Death (oil on canvas, 1915), Death in the Sick Girl’s Room (oil on canvas, 1893 and lithograph, 1896), Kiss by the Window (oil on canvas, 1891) with The Kiss IV (woodcut, 1902) and The Kiss (oil on canvas, 1897); and again, two lithographs of the famous Madonna and six versions of Vampiro, from oil on canvas (1895 and 1916-1918) to pastel (1893) to wood panel (1902).

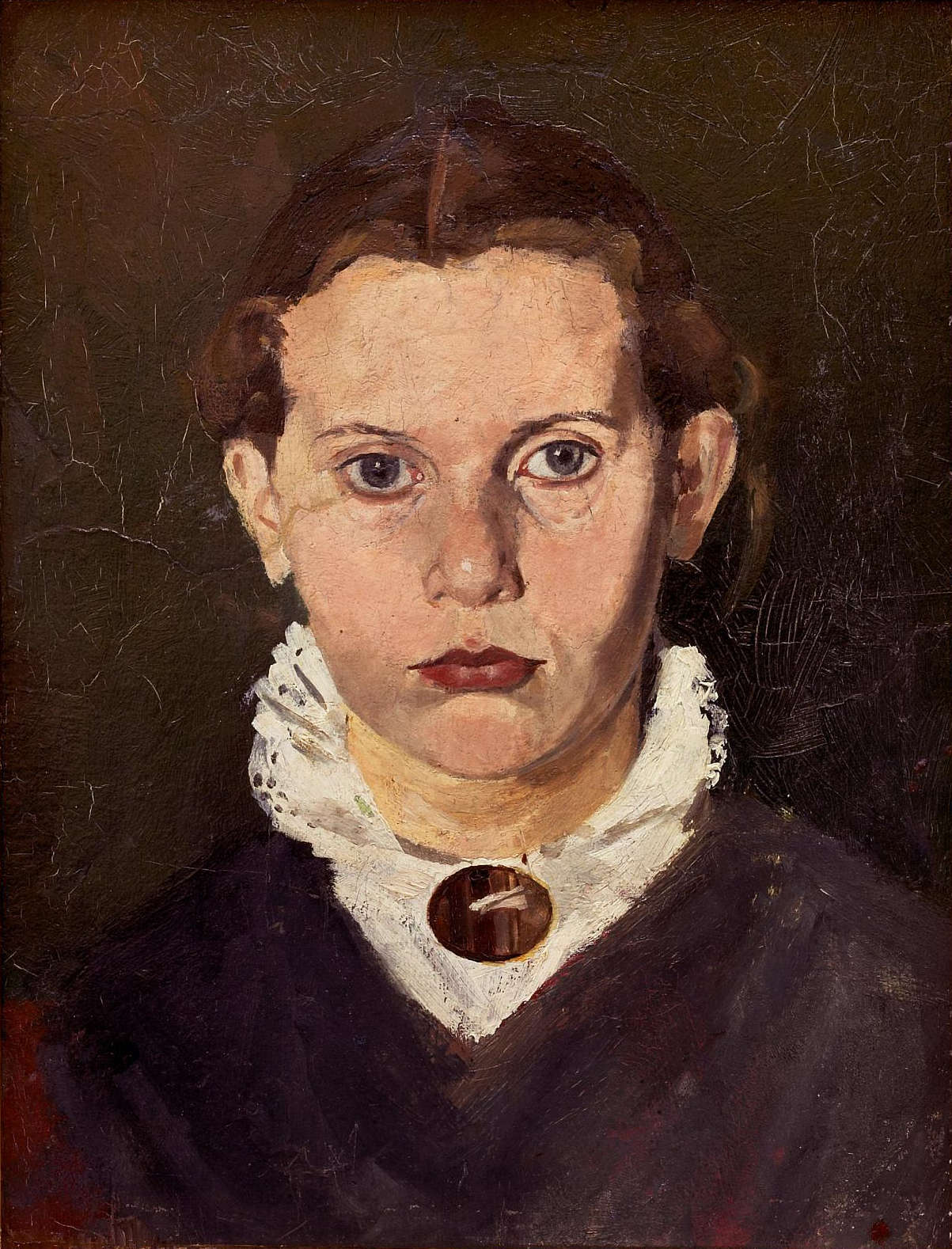

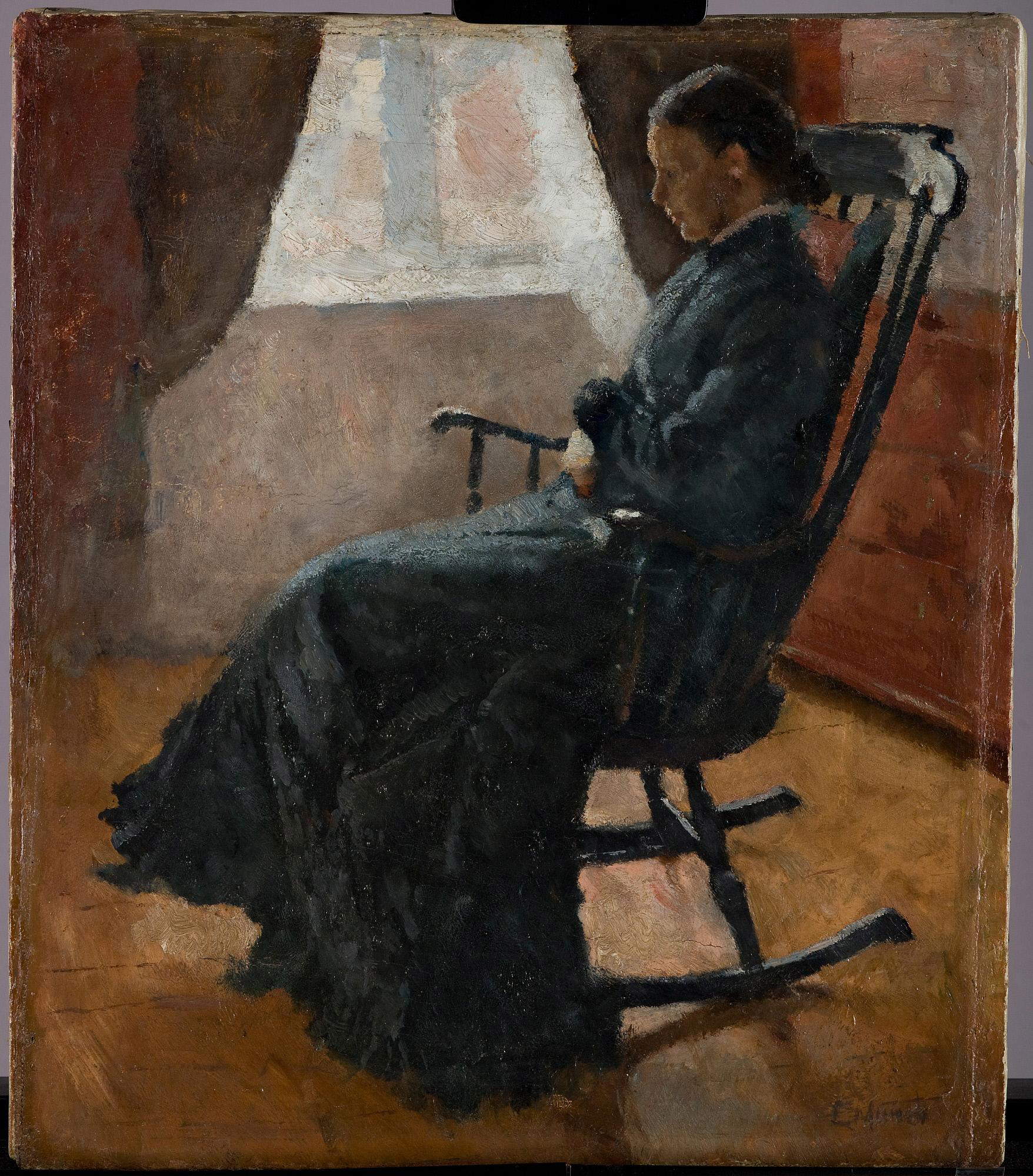

The long and at times repetitive immersion in Munch’s anguish, anxieties, obsessions and encounters with death kicks off in the first section with Melancholy, which depicts a lone woman sitting in a domestic setting, whose expression refers to the painting’s title, and with a portrait of Laura Munch, the fourth of the artist’s five siblings who began to suffer from psychological disorders from adolescence against which she struggled throughout her life. However, the painting is an example of the mixture of elements that belong to his academic training and elements that suggest a freer approach to painting, such as the portrait of Aunt Karen in the rocking chair: Munch’s mother’s sister, who moved into the Munch household when Edvard lost his mother at the age of just five to tuberculosis and who nurtured and supported his artistic talent as an amateur artist herself, is depicted here against the light and with soft brushstrokes that Munch had begun to experiment with under the guidance of Christian Krohg. Above all, however, these are works in which one senses an emotional approach in depicting the subjects influenced by an inner vision and memories. The views shown here of Karl Johan Avenue, the main street in Kristiania not far from where little Edvard lived as a child, are also the result of memories. The first section closes with the aforementioned depictions of Kristiania’s bohemian circle and a portrait of Stanisław Przybyszewski.

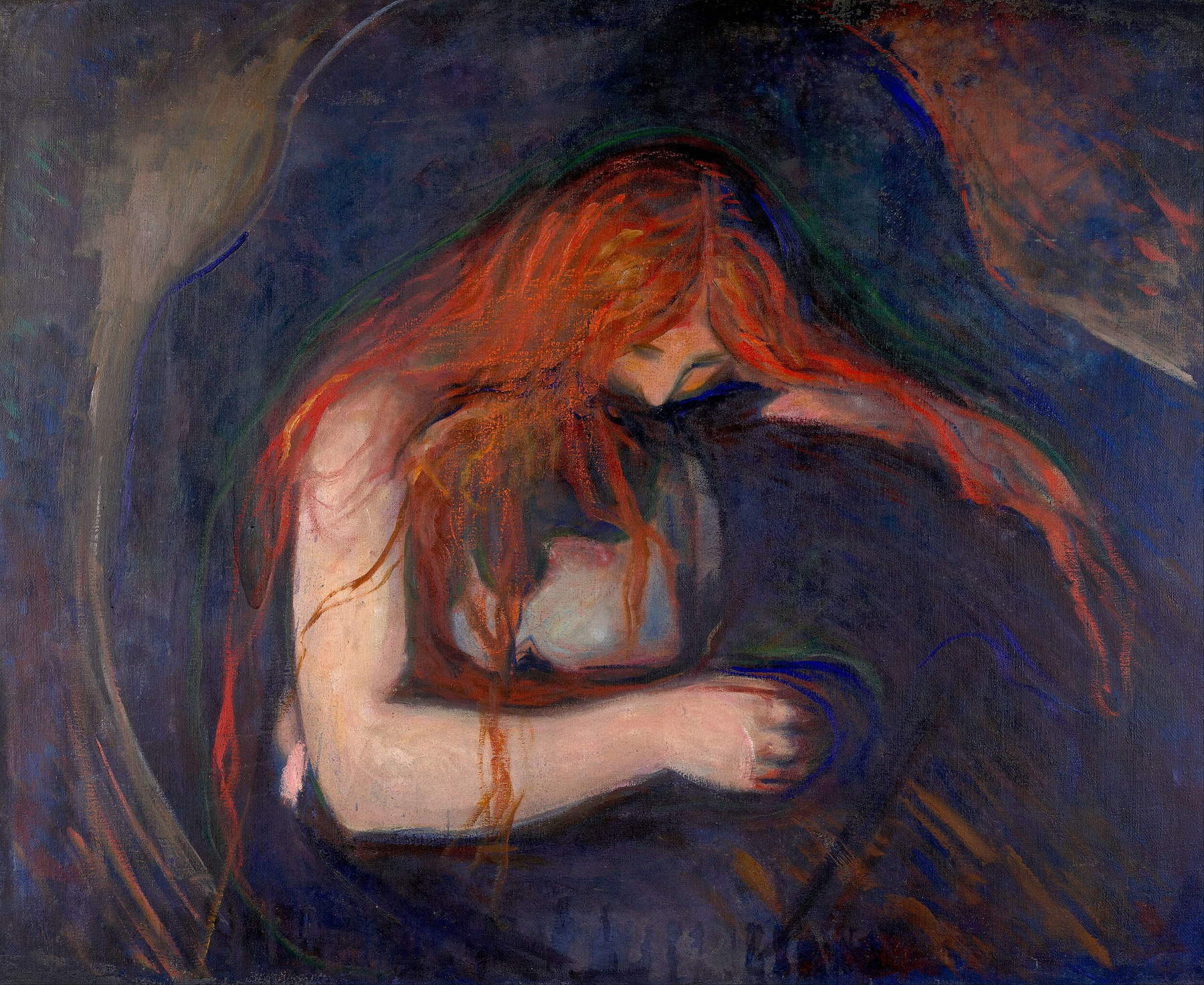

Illness and death, tragic experiences that marked Munch’s family and life, are the protagonists of the second section: the artist eliminates superfluous details and manages to capture the very essence of pain and death. In the works exhibited here, we see figures in despair or ghostly figures immersed in gloomy atmospheres that confront the viewer with the precariousness of the human condition and make him or her empathize with the pain of watching over a sick person, especially if it is a child, or the feeling of loss experienced when faced with the death of a person. These are works that recount the agony of loss, in which mourning becomes tangible in a powerful pictorial image set in a room in the home. Examples are The Sick Child, Death in the Sick Room, Struggle Against Death. From Moonlight. Night in Saint-Cloud, on the other hand, a strong sense of isolation clearly shines through. Disturbing is the painting Vision: a bodiless head with closed eyes emerges from the surface of the water, while a swan and other undistinguished forms float above its head, and still no less disturbing is the Child About to Drown. Standing out in this section, however, is Despair, where a human figure dressed in black is immersed in the same landscape as the famous Scream. In fact, the latter’s lithograph follows, accompanied by a video narrating its history and theft, and finally two woodcuts of Anguish, in which a crowd of people with alienated, wide-eyed faces walk toward the viewer, expressing the human loneliness present even in the midst of a crowd.

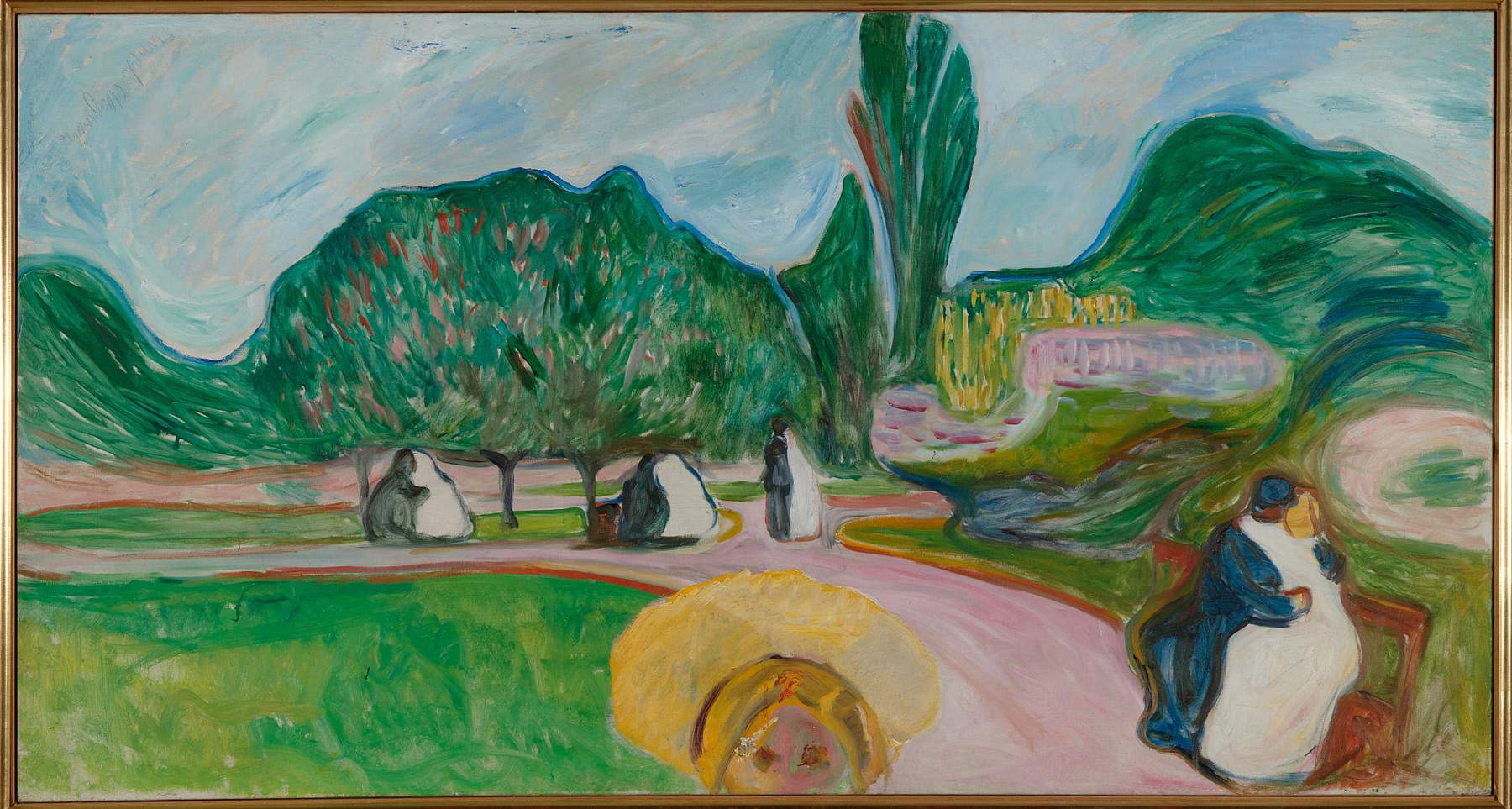

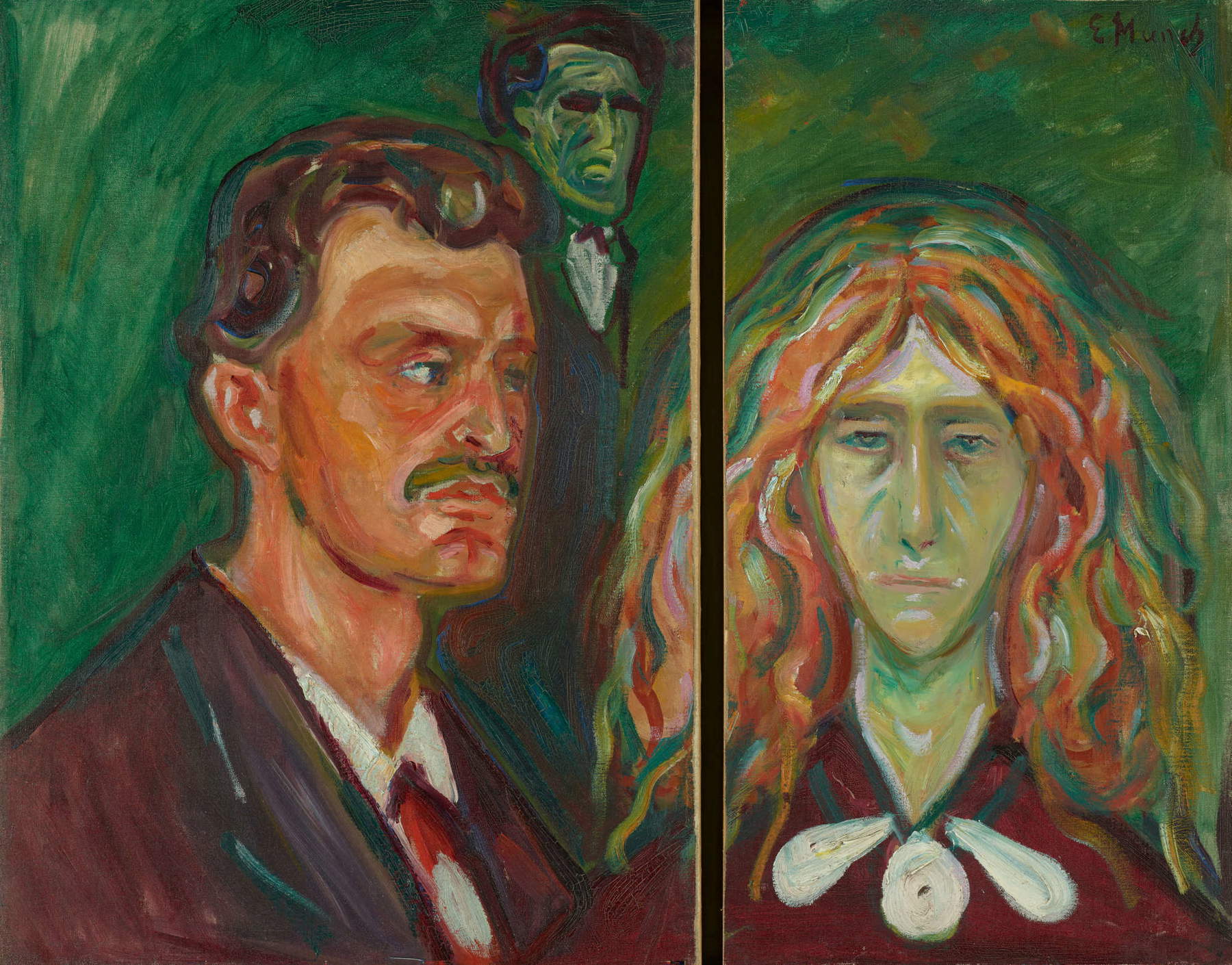

Death continues to be present in the third section: in one case it is at the helm of a sailboat in the middle of the sea; in another case, in the form of a skull, it gives a girl a kiss. But the kiss of love, as well as sensuality (exhibited are two lithographs of his very sensual Madonna), is also seen by Munch in its dual aspect: as a source of fulfillment, made explicit in paintings such as The Kiss or Kiss by the Window, in Couples Kissing in the Park or Attraction, but also in its dark side, in its destructive force, as in Vampire. The artist feels empathy for all people who are ensnared by seduction and ruined by the dissolution of love. Particularly relevant is the relationship with Tulla Larsen, the only woman Edvard Munch considered marrying: their relationship began enthusiastically but then deteriorated as he, convinced that he was incubating hereditary diseases and in need of devoting himself to his art, increasingly resisted Tulla’s desire for intimacy, leading to a traumatic quarrel in which a gunshot mutilated one of the artist’s fingers. Their relationship inspired works that explore the conflictual relationship between man and woman, where the female figure is presented as a seductress and the artist himself as a sacrificial victim: a clear example is The Death of Marat exhibited here, where, in a room, a naked man lies on a bed with one arm hanging from the mattress and his hand and wrist appear stained rust-colored; the woman, on the other hand, is standing naked and motionless like a statue. The scene might depict an erotic scene, but in fact the title suggests that the man has been murdered, in the face of the woman’s coldness. Also emblematic is the split painting with Tulla’s self-portrait and portrait on a green background, signifying the end of their relationship.

Child About to Drown Despair

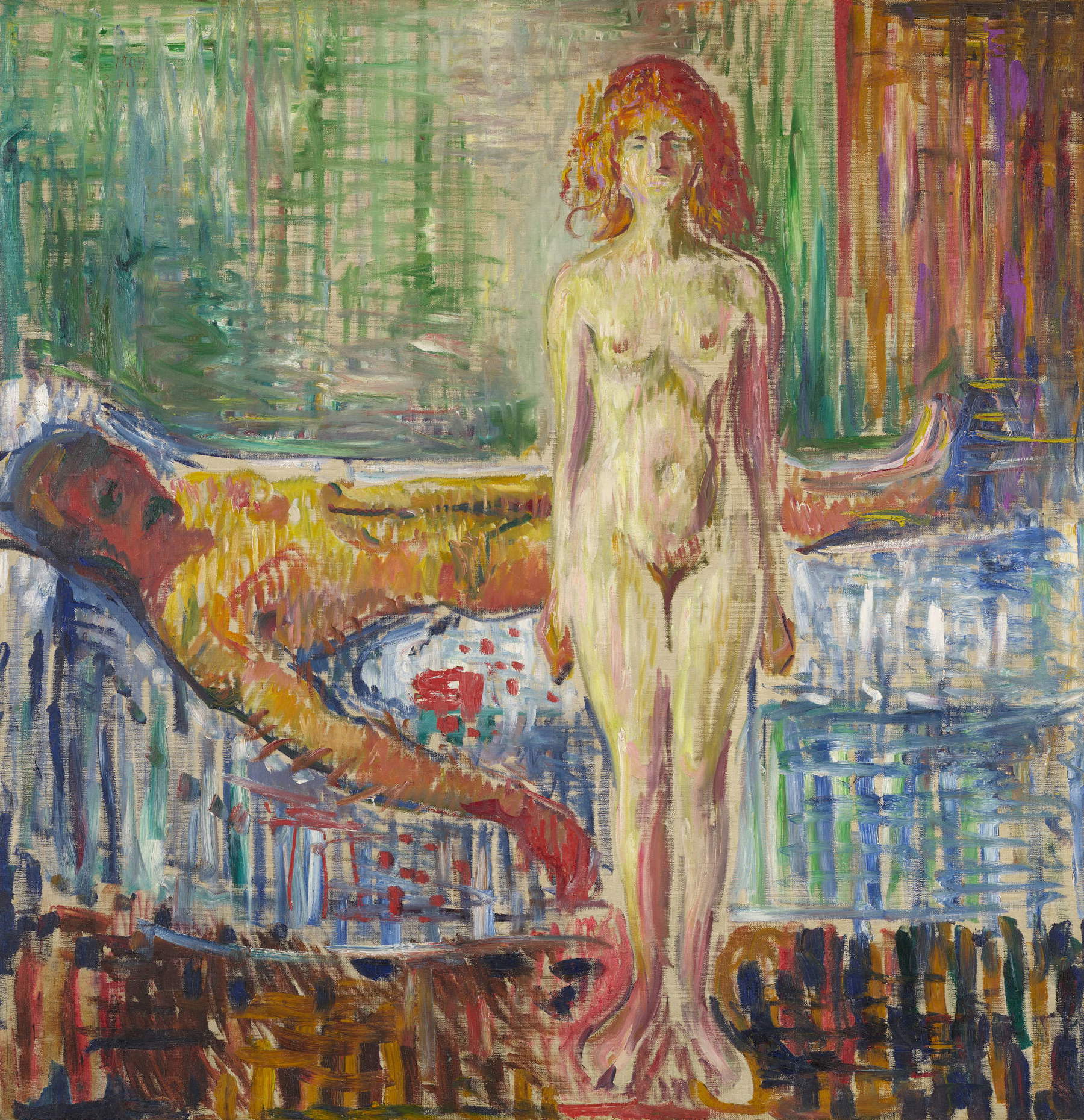

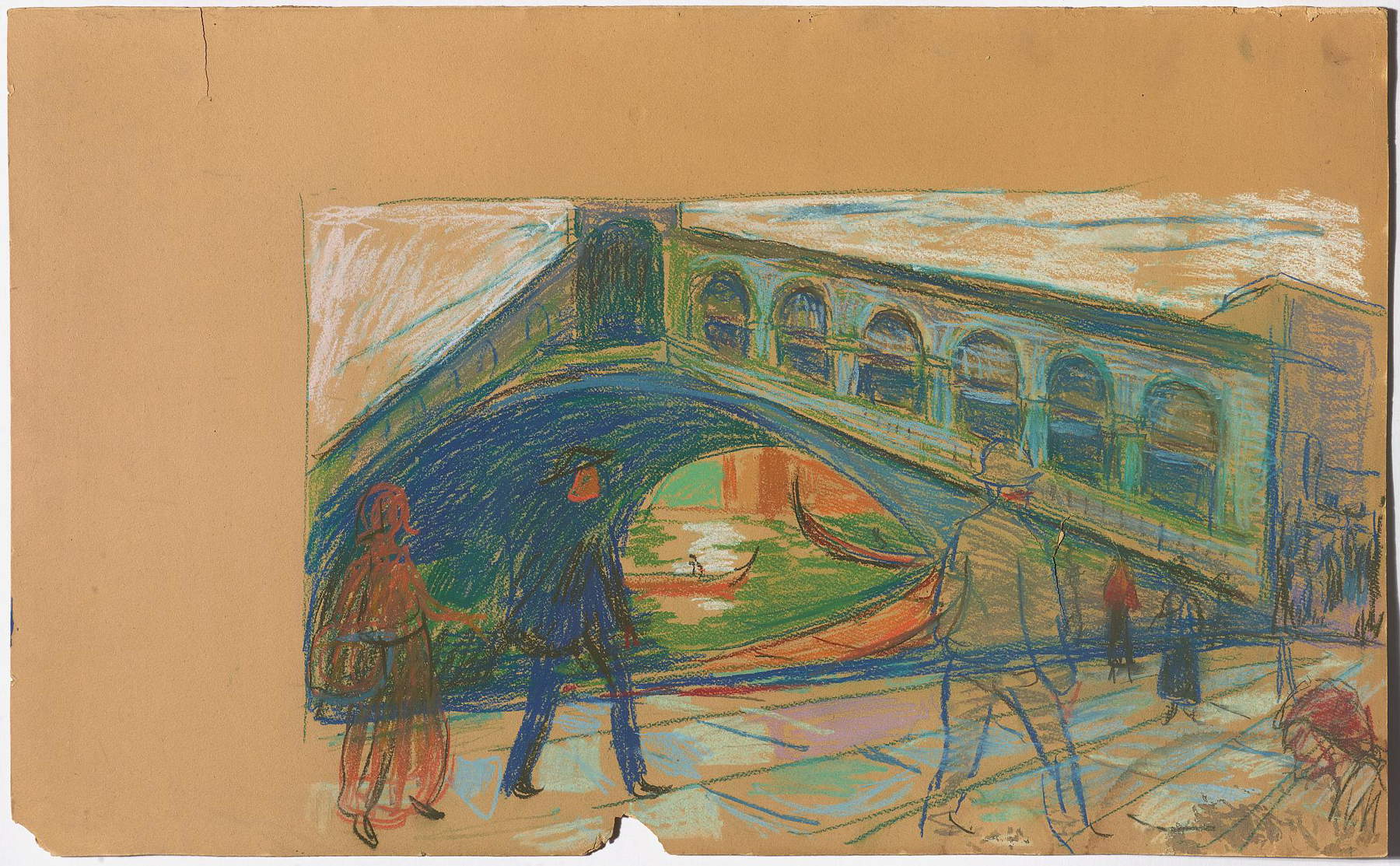

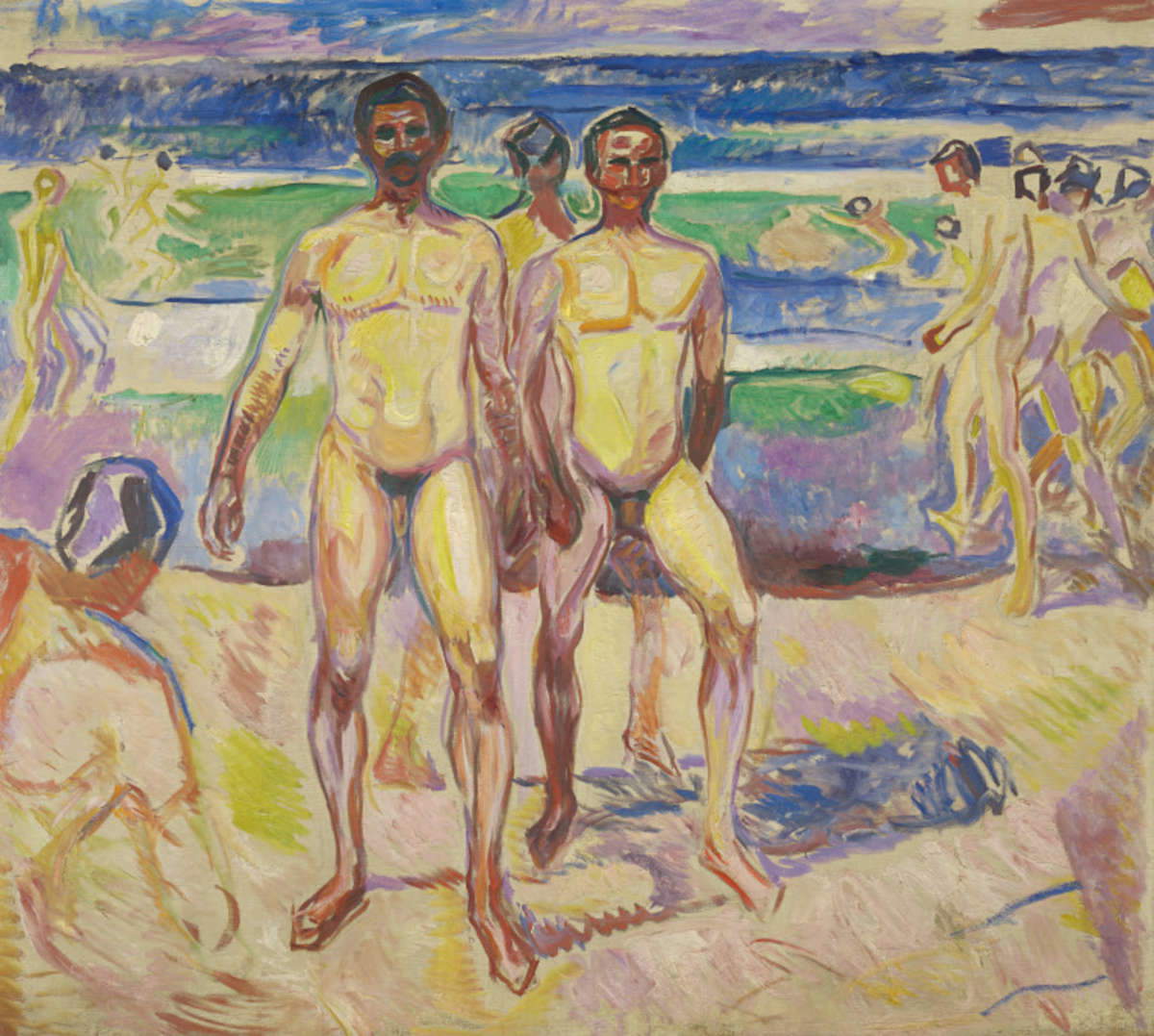

The exhibition then devotes a section to a little-known aspect of Munch, namely his relationship with Italy: he visited it for the first time in 1899 and then again in 1900, 1920, 1922 and 1927. During his stays in Italy, he had the opportunity to engage with Renaissance traditions and was particularly impressed by Michelangelo (he described the Sistine Chapel as the “most beautiful room in the world”) and Raphael. Of the Urbino he executed a portrait on paper, exhibited here, but works such as Rialto Bridge, Venice and The Tomb of P.A. Munch in Rome also testify to his love of Italy and Italian artistic heritage. Munch was also fascinated by doctrines that united matter, energy and spirit, such as monism, and by the possibility that the universe was pervaded by invisible forces, such as solar radiation, electromagnetism, telepathy, and cell growth. Works such as Waves, Men Bathing or Naked Men in a Landscape reflect this interest. For Munch, nature and the human body were deeply interconnected: his cosmological vision did not separate the physical world from invisible energies; this led him to create a visual language in which tangible reality and the invisible merge. All material things, both living and inanimate, were for him interconnected. There is also a photograph showing the artist naked, from behind, in the seaside resort of Warnemünde.

The Sun, Alma mater, The Story and Toward the Light that we encounter below, on the other hand, refer back to the monumental murals for the new Great Hall of the Royal University of Frederick (now the University of Oslo): for the institution’s 100th anniversary , a competition was announced for the paintings, and Munch worked seven years to secure the commission. He designed eleven canvases to celebrate the nation, the university and its academic disciplines, with The Sun at the center, symbolizing both the institution’s own mission to enlighten students with knowledge and the energy that animates all things. However, the committee charged with selecting the winner called the murals colorful “sketches” and never officially accepted them, but they were later purchased by the artist’s supporters and donated by them to the University and then installed in 1916, after other works related to the project were exhibited throughout Europe thus stimulating positive critical reception.

We continue in the penultimate section where the numerous self-portraits made by Munch are brought together: the artist depicts himself with a cod head on his plate, in hell, in front of the wall of his house or with his model. Through the self-portraits Munch explored his own psyche and the passage of time. The Self-Portrait between the Bed and the Clock is emblematic of his confrontation with death and aging. Indeed, in the latter, the elderly artist depicts himself standing in his bedroom with his hands dangling down his sides, those hands that used to be active, with which he drew and painted, are now inert.

The exhibition concludes with a section intended to give an understanding of how Munch’s art influenced 20th-century art, anticipating Expressionism and Futurism. In fact, the viewer is inclined to participate in the emotions conveyed by the scenes depicted, as in On the Steps of the Veranda or in Wall of the House in the Moonlight, where in both cases the shadow of an elongated figure is noted, suggesting the presence of the artist or another entity, toward which the woman in the first painting is looking. It is, however, a hint oftangible invisibility. A shadow, this time more shapeless, so much so as to create in the viewer a certain uneasiness, is also in theSelf-Portrait in Hell exhibited in the previous section, nonetheless hinting back to those invisible forces mentioned earlier. Munch used innovative techniques and bold perspectives to depict landscapes that lead into his personal construction of space, which inspired avant-garde movements of the 20th century. His painting style with broad, bold brushstrokes continues to exert a strong influence, a sign of his modernity. Paintings such as Starry Night and The Girls on the Bridge exemplify his innovative visual language, which transcends the traditional limits of representation to explore the intimacy and emotions of the human soul.

Nothing exciting about Munch’s return to Milan, however, other than bringing works to Italy that would otherwise be seen in Norway. Disappointment in finding masterpieces such as The Scream and Madonna exhibited only in lithograph form, and in my opinion, beyond the intent, it seems to me that there has been too much focus on Munch’s anxieties, which are fundamental to his art, but which as stated in the intent go far beyond his biography since they are influenced by the philosophy of the time and Freud’s psychology that foregrounds the unconscious. These aspects, this “articulated vision” alluded to, is not well perceived in the exhibition. The section on Munch in Italy is interesting, but unfortunately not very thorough.

The catalog, in which the lengthy panels in the exhibition are not shown, includes three essays: the first devoted to Munch’s relationship with Italy, the second, written by curator Patricia G. Berman, devoted to visual perception and inner vision, to the inner eye as subject, thus the subjective dimension of Munch’s painting, while the third essay explores the relationship between Munch’s artistic evolution and contemporary developments in perceptual sciences. Then there are two contributions by writers Melania Mazzucco and Hanne Ørstavik: I Am a Romantic and Who Am I, which relate to works on display in the exhibition. Unfulfilled expectations for one of the most anticipated exhibitions of the year.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.