A Little Tour on the Grand Tour. What the exhibition at the Lia Museum in La Spezia is like.

Collecting ancient art also follows trends. Those who look at this world from the outside may find it hard to believe, but it is so, it has always been so, and there is no reason to believe that it will cease to be so. And although it often happens that one is forced to read hagiographies of collectors who never bowed to the trends of the moment, the fact is that there is nothing wrong with buying a painting, or a group of paintings, because the name of their author is among those trending in a given period. As long as the work purchased, even if à la page, still touches the heart of the buyer. Otherwise it is just soulless show-off. Now, as chance would have it, Amedeo Lia, who was among the greatest collectors of the last century, harbored a sincere passion for Venetian arts from almost every century, and as chance would have it, between the 1980s and the early 2000s, Canaletto was one of the fashionable artists among the wealthiest collectors. There was a time, in the recent history of collecting, when a Canaletto was considered a kind of quality mark, an endpoint of a collection, or more trivially a must-have. Those who could not get their hands on a Canaletto were content to replenish their collection with some other vedutista. Amedeo Lia managed to get his Canaletto: a delightful capriccio with a Gothic building inside which clearly echoes the painter’s British sojourn, recalled by the palace in the background that is identical to King’s College Chapel in Cambridge. A landscape in which, as he often did, Canaletto mixed real elements and scenes of invention. A work of undoubted autography, specified Federico Zeri, who was Lia’s closest ’consultant,’ so to speak. And alongside this caprice, alongside this sparkling essay of Canaletto’s art, Lia was able to build a dense, rich, complete nucleus of Venetian vedutisti: very few museums in Italy can show the public a similarly balanced and accomplished corpus . Good then that Canaletto was in fashion 30 years ago, one would say.

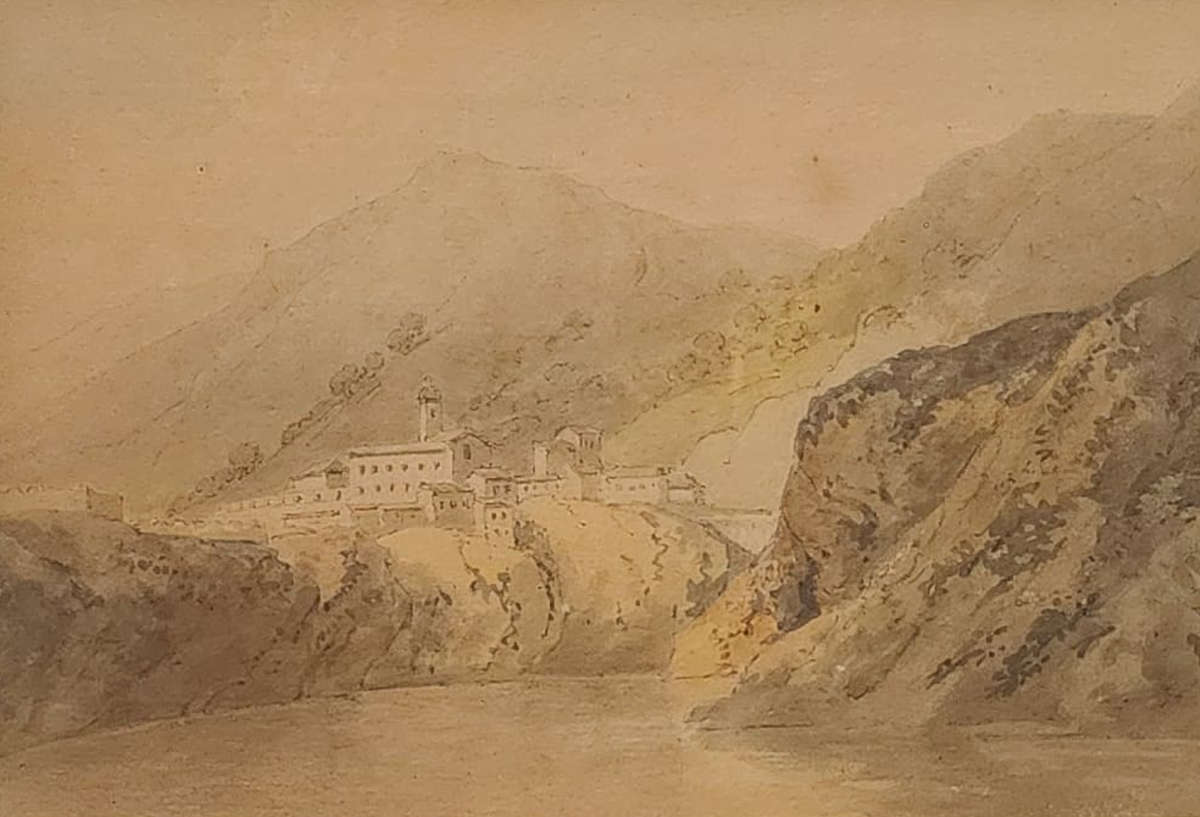

There are, in the eighteenth-century collection of the Lia Museum in La Spezia, the civic museum that grew out of the engineer’s collection, also landscapes depicting other parts of Italy. Amedeo Lia had, however, one would say, a particular passion for Venice. Eighteen years ago, an exhibition-focus on all the Venetian art in his collection-was organized at the museum. This year, however, the collection’s core of 18th-century views provided a good excuse to mount an exhibition devoted to the Grand Tour(The Art of Travel. Italy and the Grand Tour), organized by taking advantage of the museum’s own works, with some support coming from a good number of external lenders: normal practice for the Amedeo Lia Museum, which has never organized major exhibitions, but has always had the ability to bring to the shores of the Gulf of Poets pieces of definite interest with the aim of delving into the theme of the moment. And this time the institute has built a sort of condensation of the last exhibitions that have been dedicated to the Grand Tour topic: the great exhibition at the Gallerie d’Italia in Milan in 2022, perhaps the most complete and impressive exhibition on the Grand Tour that has been held in Italy (not counting the one at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome in 1996: it was a stage of an exhibition that originated at the Tate in London), and the one at Palazzo Cucchiari in Carrara in 2016, come to mind. It is curious, moreover, that two of the major exhibitions on the Grand Tour were held in two cities separated by just thirty kilometers. Two cities, Carrara and La Spezia, that were marginally touched by the travelers who descended from northern Europe, crossed the Alps, and then went down to Florence, to Rome, to Naples and then back up in the direction of Venice and from there back home. If, however, the Carrara exhibition, albeit with all the limitations of the case (the bulk of the material came from a single lender), had nevertheless devoted an entire room to the Apuan landscapes, offering the public the opportunity to observe various glimpses of these lands at the time when some of the most daring grandtourists s’were set on going to see the marble quarries, the Lia’s exhibition dedicates to the landscapes of the Ligurian Levant nothing more than a beautiful watercolor by William Turner, the only evidence, in the tour itinerary, of the albeit vivid interest that painters and travelers who happened to visit Italy between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries cultivated for the Gulf of the Poets.

True, the gulf was not included among the milestones, yet many have passed through these shores. Politicians, writers, poets, painters. George Dennis, who was a diplomat and archaeologist, had stopped here because he wanted to study the ancient city of Luni. Samuel Rogers, in his poem Italy, dedicated splendid, evocative verses to the gulf (“The day shone, and over the precipice, / [...] Rolled a steamy sea. I seemed to proceed / Along the extreme edge of this, of our world; / But soon the waves retreated, and we caught sight / Not vaguely, though the lark was still silent, / Of your gulf, La Spezia. Before the morning cannon, / Before the day’s first ray, we stood there; / And not a breath, not a murmur!”). Denis Florence Macarthy, an Irish poet, wrote a lyric about the fireflies he had first seen amid the myrtle bushes along the La Spezia coast (“In many a sweet bay of Liguria / The myrtles shine green and bright, / Shining with their snowy blossoms during the day / And blazing with fireflies at night; / And yet, in spite of cold and heat, / They are always fresh, pure and sweet.”). Of Byron and Shelley it is even superfluous to speak. And then the artists: Cozens, Klenze, Blechen, Pyne, just to mention the best known names. There is, in short, plenty of material for another exhibition.

The Art of Traveling focuses primarily on the four “capitals of the Grand Tour,” as we might call them: Venice, Rome, Florence and Naples, in order of how they are presented to the public, with the works arranged within the excellent, original layouts designed by the Tub Design studio, which revolutionized the Sixteenth and Eighteenth-century rooms (works not functional to the exhibition were moved to the large room usually reserved for temporary exhibitions) to welcome visitors with a lively narrative, aimed at enhancing the works especially where the layout of the exhibition is weakest: the room dedicated to Naples, for example, has been transformed into the room of a Pompeii domus to display some drawings of the Posillipo School, and the late 19th-century watercolors of the Neapolitan painter Vincenzo Loria, who was director of the Pompeii excavations and whose paintings were intended to document the wall decorations that had been preserved for centuries under the ashes of Vesuvius. The four sections are anticipated by an introductory room that is instead dedicated to the reasons for the journey. Where and when did the need to embark on the Grand Tour arise? It should be borne in mind that it is a phenomenon that is not as uniform as one might think: the formative journey through Europe was a codified usage as early as the mid-seventeenth century (in the opening of the exhibition it is rightly recalled that the term first appears in Richard Lassels’ Voyage of Italy , published in 1670: somewhere between a guidebook and a travel report, the work provided the reader with descriptions of cities and monuments that the English priest had seen in Italy), and which lasted until the late 19th century. In the room devoted to Florence, one will be enchanted by a view painted in 1844 by Giovanni Signorini, father of the great Macchiaiolo Telemaco, and displayed next to a splendid painting(The Arno at the Peach Farm of San Niccolò), one of the best in the exhibition, by another forerunner of the Macchiaioli, Lorenzo Gelati, who executed it as late as 1860. At the time, to be sure, a class of bourgeois collectors was forming in Tuscany who appreciated the views of their cities and would become the main supporters of local painters (Signorini and Gelati’s collectors were mainly Tuscan), but there was no shortage of a large, refined international clientele who would continue to buy landscapes as travel souvenirs even in the 19th century, while relations between artists and patrons often grew closer. The relationship between Giovanni Signorini and the English consul Christopher Webb Smith was not so distant from the one that bound Canaletto to Joseph Smith, although it was not equally decisive for the fate of his career.

The Grand Tour is thus a custom that, as we understand it in the common imagination, lasted a couple of centuries, involved travelers of different nationalities (although we tend to associate it with the British aristocracy of the Age of Enlightenment, but travelers who took the route to Italy came from all parts ofEurope), could last a few months but also a few years, followed traditional routes that were, however, often varied (typically the southernmost point was Paestum, but there were travelers who went as far as Sicily), and also experienced abrupt interruptions (by the time of the Napoleonic wars, cross-Channel travel had drastically thinned out). To set out on the journey, one needed to have a minimum of preparation, organization was needed, and it was necessary to know trusted people who could act as references at the various stages of the journey (many former travelers, especially English, decided to settle in Italy and start what was a very lucrative profession at the time: the tour guide!). And the Grand Tour is also a cross-cutting topic, since it covers the history of politics, the history of literature, the history of art, the history of collecting, and the history of tourism. The Lia exhibition deals with it in the most classic way: with the landscapes of the Grand Tour capitals, so much so that it could easily have carried a title like Landscapes of the Grand Tour or something like that. However, there is time to evoke the atmospheres that travelers found upon their arrival in Italy: here then is the first section of the exhibition, perhaps the most intriguing, precisely because it is able, with a restricted selection of works, to project the visitor into eighteenth-century Italy, among casts of masterpieces of classical statuary, glimpses that the traveler could see on his way (the countryside with peasants described in anArcadian canvas by Giuseppe Zais, the Levante Ligurian coast as seen from the sea in Turner’s aforementioned watercolor), personal effects that grandtourists carried with them (the nécessaire comes from the nearby Seal Museum), portraits of those who in Italy had ’had been and, as was the custom for the gentlemen who stayed in Rome on their Grand Tour, took home their own image against the backdrop of the ruins of ancient Rome, preferably painted by a talented artist. The imposing effigy of Henry Peirse, a life-size portrait by Pompeo Batoni on loan from Palazzo Barberini in Rome, is one of the reasons the exhibition is worth visiting: it is one of the rare portraits of grandtourists in Italy’s public collections, and it is one of the best examples of the “tourist portraiture,” we might say, with which Pompeo Batoni would procure a steady source of income throughout his life, and it fully embodies the image the traveler wanted to preserve of himself: a young aristocrat (for such was the condition of most who embarked on the Grand Tour), dressed in an elegant but practical outfit suitable for travel (here a red red redingote covering a light white silk suit), proud of his presence in Rome, proud to be portrayed near those antiquities he had studied and dreamed of, and it matters little whether they were real or fake, since the large white marble crater placed next to the Ares Ludovisi does not seem to match reality, but rather seems to be a figment of the Lucca painter’s imagination.

It has been said that the modus operandi of the Amedeo Lia Museum is to mount exhibitions with quality pieces that strengthen its own collecting nuclei: it is worth lingering, then, on the four tempera paintings by Francesco Guardi, lent by a private collection, which investigate as many views of Venice in a phase of the great 18th-century painter’s career not yet fully oriented toward those misty and melancholy views that constitute the most innovative outcome of his production, or on the delicate watercolor by Ippolito Caffi (a view of Castel Sant’Angelo) which, together with a more naïve view of the Pantheon by Claude Nattiez, cleverly complements Caspar van Wittel’s extraordinary view from the Quirinale, Giovanni Paolo Panini’s Capriccio con Colosseo and Marco Ricci’s Capriccio con rovine , or three superlative images of Rome preserved in the Lia Museum’s permanent collection, not to mention the works by Signorini and Gelati mentioned above. It is also a way of investigating the theme of the development of landscape painting in the 18th century: we go from the descriptive and lenticular vedutismo of Caspar van Wittel to the visionary rovinismo of Giovanni Paolo Panini, from the scientific, crystalline and balanced vedutismo of Canaletto to the atmospheric vedutismo of Francesco Guardi, crossing the quasi-technical vedutismo of Bellotto and the imaginative vedutismo of Marco Ricci to arrive at the taking from life of Signorini and the veduta of Gelati that already looks to the France of Barbizon and acts as a prelude to the painting of macchia. A sequence, moreover, that is all Italian: the exhibition lacks almost entirely landscapes by foreign painters, who also constituted an important presence in the Italy of the Grand Tour.

A sort of manual of Vedutism unfolds before the eyes of the public of the Lia Museum under the guise of the Grand Tour exhibition, with a selection that, from this point of view, is even more complete than on other occasions (the Milan exhibition, for example, lacked works by Francesco Guardi): those who want to delve into landscape painting in Italy in the 18th century would do well not to miss this exhibition that is perhaps a little underestimated by the public of big events, by the public that travels on weekends to see exhibitions. It is known, after all, that these precise views were much appreciated by grandtourists: “precisely because of the rational restitution of the appearance of the places visited,” wrote Cesare De Seta who is one of the greatest Italian scholars of the Grand Tour, “they will be able for decades and miles away to reverberate their memory.” A memory taken from afar: travelers were primarily interested in bringing back home the face of the cities they visited. The viscera, on the other hand, was a subject they had little passion for, and besides, not many artists were interested in the social reality of those places: to understand what was going on in the streets of the cities better to turn to painting such as that of Giacomo Ceruti or Alessandro Magnasco (both, moreover, present in the permanent collection of the Lia Museum), which, however, did not ignite the enthusiasm of the grandtourists, who in their minds had a certainly clearer image of Italy. A bit like today’s tourists.

Thus, an image of Grand Tour Italy emerges from the La Spezia exhibition similar to the one that must have formed in the hearts and minds of travelers three hundred years ago. A dreamy and bewitching idea, suspended somewhere between what the travelers saw and what they dreamed of, a middle ground between landscape photography and evocative imagery à la Piranesi, a name, moreover, absent from the exhibition, despite the fact that his engravings had aroused the desire for Italy in so many. Similarly, even with an entire room devoted to Naples, there is minimal mention of the fascination that the ruins of Herculaneum and Pompeii, discovered just before the middle of the 18th century, had exerted on the travelers of Europe who decided to set out partly because they were ignited by the desire to see these cities of which they had only heard. At that time, after all, the only social was the experiences and reports of those who had been there in Italy.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.