A journey through time with photography in Venice. Chronorama, photographic treasures of the 20th century

The name “chronorama” suggests one of those devices designed until the nineteenth century to reproduce moving images. Chrono, the god of time, and -rama, the Greek suffix that brings back vision, give the idea of a sequence of pictures scrolled quickly one after another exploiting visual perception to suggest a change, a movement, an evolution. This is the idea that evokes Chronorama. Photographic Treasures of the 20th Century , the exhibition on view at Palazzo Grassi in Venice until Feb. 7, 2024, curated by Matthieu Humery. A sequence of 407 works, mainly photographs, but also some illustrations, created by 180 artists between 1910 and 1979 for Vogue, Vanity Fair, House & Garden, Glamour, GQ and other magazines, and now collected in the Condé Nast publisher’s photographic archive, acquired in part by the Pinault Collection, owner of Palazzo Grassi.

“Telling the time in which one lives is not always easy. Who is important? What is relevant right now? What is really happening? The answers can give rise to fiery debates,” Anna Wintour, Chief Content Officer of Condé Nast, and Global Editor Director of Vogue, tells in the introduction. While these questions have guided the choices of successive editorial directors at the helm of some of the century’s most famous magazines, today their archives allow for an original account of the 20th century, in the evolution of society, through changes in fashion and the development of the photographic gaze.

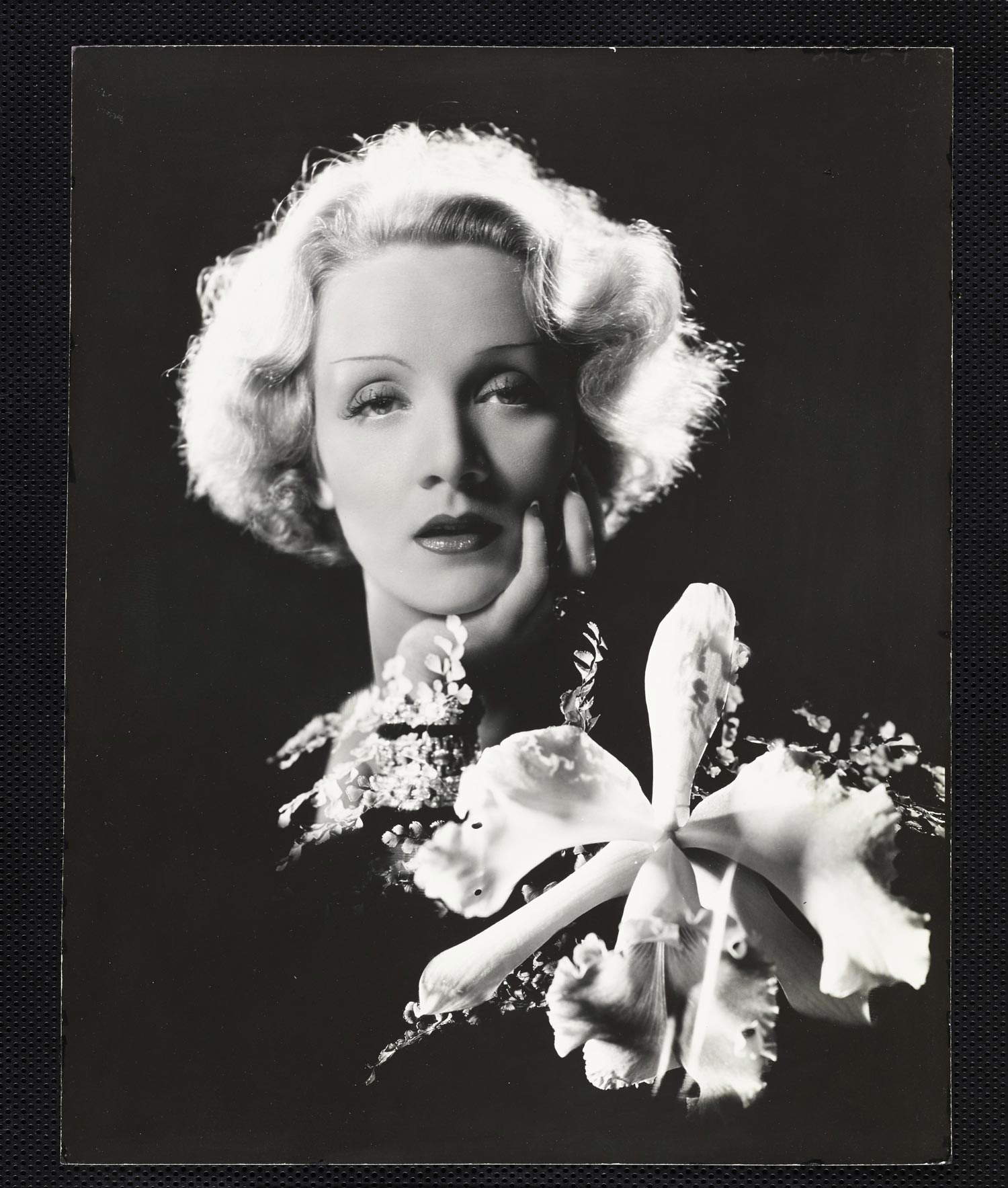

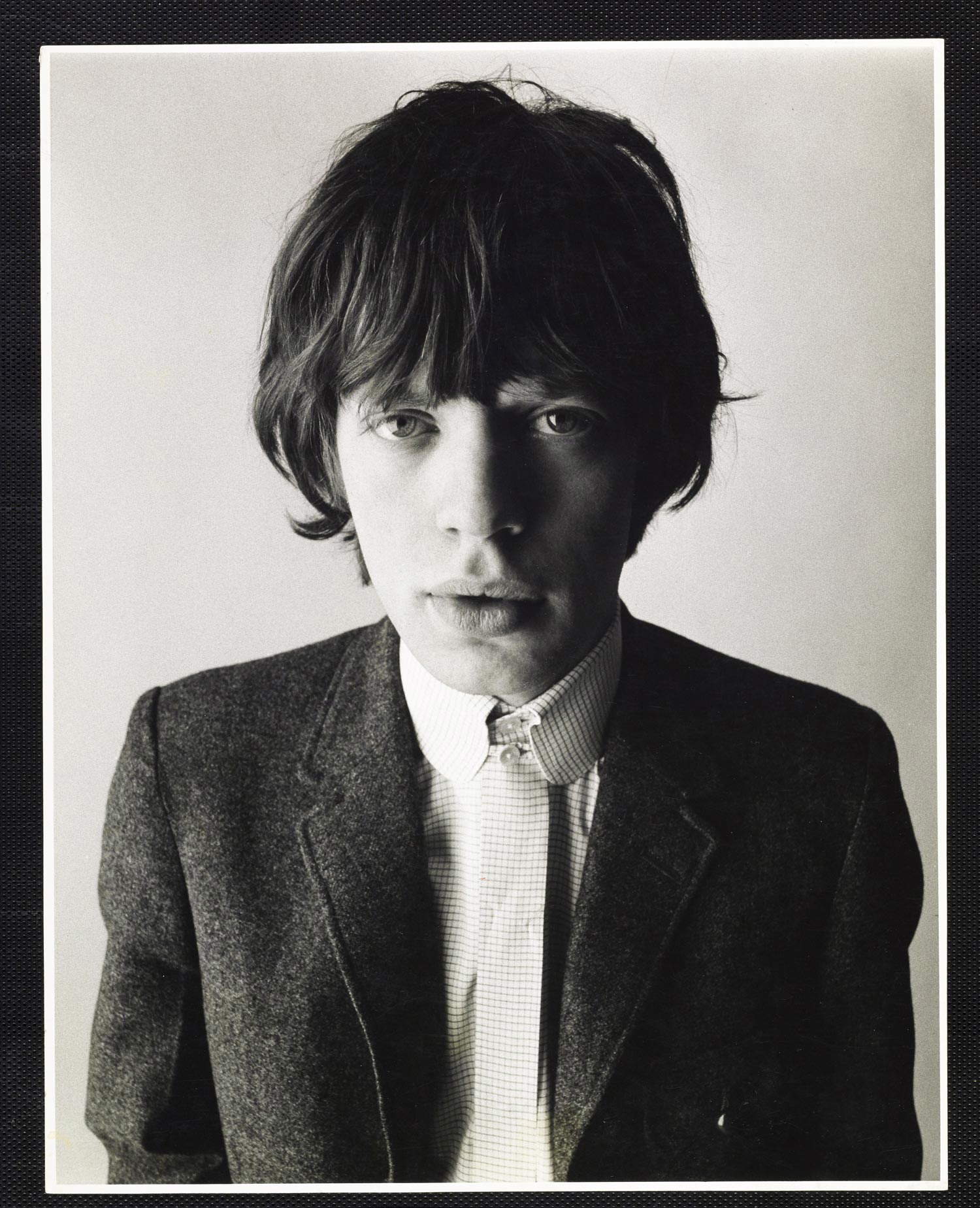

But let us proceed in order... chronologically, like the layout that presents the works divided by decades, with an almost scientific approach. After all, it was perhaps the only possible attempt to find a common thread in an archive as immense as it is varied. From the fashion covers by George Wolfe Plank that open the exhibition, we quickly move on to photographic portraits of entertainment personalities, from cinema to theater, but also the great names of literature, and the history of the twentieth century. There is a succession of truly representative faces of the last century: Charlie Chaplin, James Joyce, Henri Matisse, Marlene Dietrich, Jesse Owens, Ernest Hemingway, Mick Jagger, Anna Magnani, Marcello Mastroianni, Karl Lagerfeld, Richard Avedon, Twiggy, and many more. There is no shortage of fashion photos, architectural shots, still lifes, and photojournalism.

Set-ups of the

Set-ups of the Set-ups of the exhibition

Set-ups of the exhibition Set-ups of the

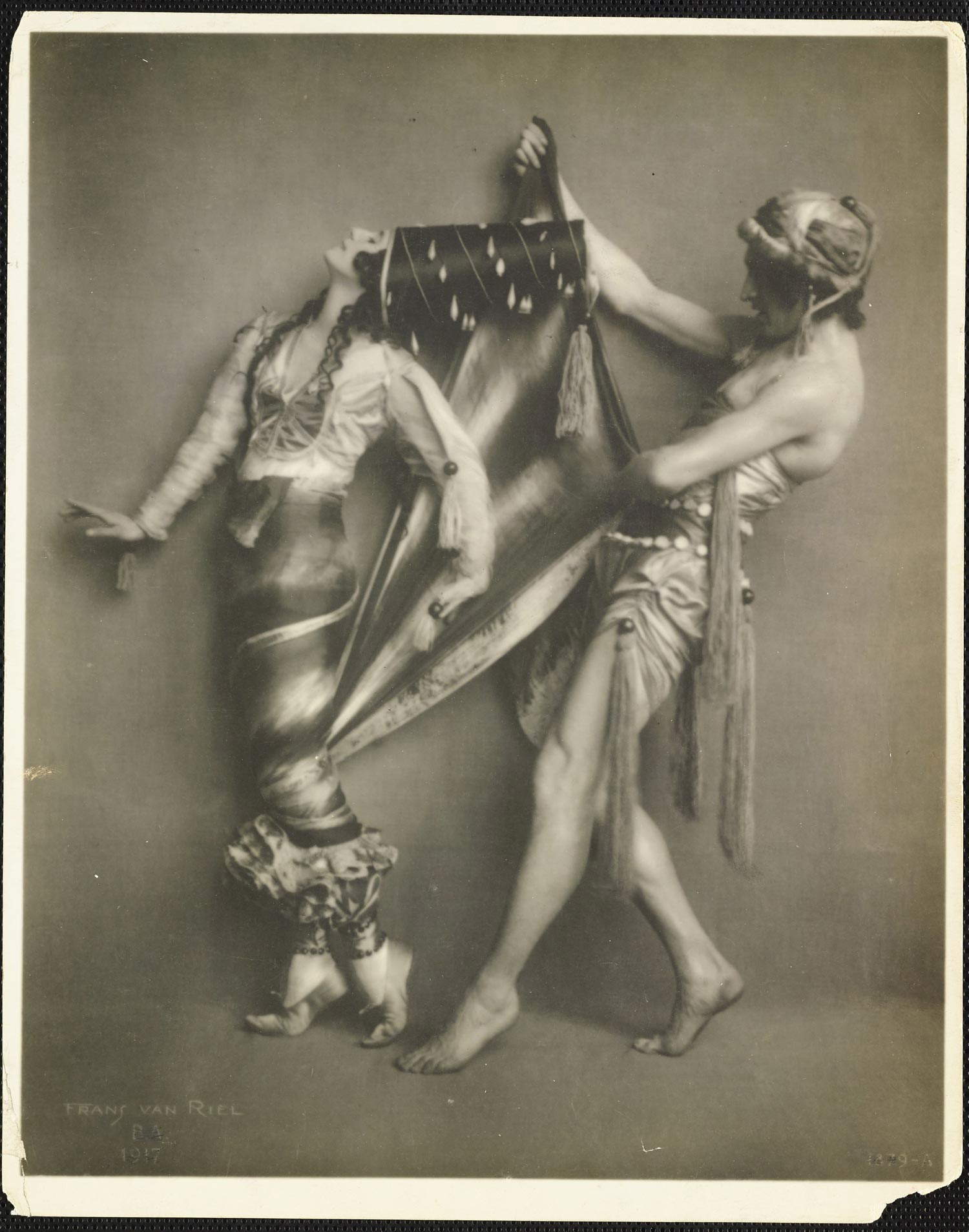

Set-ups of theFamous faces and others less so such as The first woman to wear pants in public. Dr. Mary Walker as the caption on the back of a 1911 print by Paul Thompson about which the podcast Chronorama also tells. Snapshots of the Twentieth Century, produced by Chora Media to accompany the exhibition. A photo taken for Vanity Fair but never published, probably because the publisher had failed to counter the conservative instructions of owner Condé M. Nast. Yet this second decade of the 1900s from which the exhibition’s narrative begins was a time of great renewal for society, for technology, art, and fashion. It was in 1913 that American audiences first saw Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending the Stairs, which would change the way art was conceived; in the same years the Ballets Russes-founded in 1907 by Sergei Djagilev-were known to the world, changing the idea of music, set design, and costume. And so étoile Anna Pavlova, considered by many to be the best ballerina of all time, can rightfully enter the pages of newspapers in Franz Van Riel’s 1917 photo.

In the 1920s, when the world still seemed destined for a positive development, optimism and lightness, fashion and spectacle become the protagonists of images. Adolf de Meyer, considered the first fashion photographer, emerges, but so does Edward Steichen, who in a famous photo in the exhibition Models sitting on George Baher’s yacht (1928) portrays among others Lee Miller, who shortly afterwards would also become a famous photographer. And on display is a photo of Joséphine Baker (taken by George Hoyningen-Huene in 1927), perhaps one of the first black arists to gain a space in the collective imagination.

Technological innovation, the zeitgeist, are prominent again in the 1930s, where Sherill Schell’s 1930 photo of theEmpire State Building features the skyscraper that would be inaugurated only a year later. Some images then remind us that the last century was not only one of unbridled consumerism, but also one of the greatest tragedies, when even the most glamorous magazines could not ignore what was happening in Europe. And so in the exhibition we see Cecil Beaton’s photos, Paternoster Row, London, after bombing (1940) but also Robert Doisneau’s and Lee Miller’s reportages in the Paris of 1944.

Then the images changed in the early postwar period, hand in hand with a new economic boom the photographs gave more space to fashion, with female silhouettes again swathed in corsets, architecture and to luxury cars, but also granting a space to a photographic research and experimentation now clearly influenced by the world of advertising. Colorful headscarves and miniskirts became expressions of the sexual liberation of the late 1960s, published alongside images of early journeys into the cosmos.

“The magazines published by the legendary publishing group reflect the effervescence of a society that conceives time as an endless movement, always in search of the new,” says Bruno Racine, Director and CEO of Palazzo Grassi - Punta della Dogana. If History had an Instagram page, I would imagine it exactly like this. But as social media has taught us, we cannot help but question how objectively these images do, or do not, represent reality.

Condé Montrose Nast’s original idea was to create magazines for elites, and in this lens the images were always modified by retouching, which after all has been an integral part of photographic research since its inception. “Its legitimacy has been debated since photography’s beginnings and often continues to be questioned today,” point out Matthiew Henry and Andrew Cowan, the exhibition’s historical advisor, “and not only in relation to the perfection of bodies that reinforces a distorted image of the female ideal.” In fact, retouching over time had several purposes: it could accentuate the drama of a scene, focus attention on a detail, enhance the dynamism of the image, or even just play with reality by creating surreal overlays.

The twentieth century was the century of the image, and this exhibition tells the story of how the Western world built its language in images step by step, through experimentation, trial and error, and innovation. The close collaboration with photographers of every era, which is a founding element of the identity of the Condé Nast publishing group, allowed the development of some of the greatest talents of photography of the last century: Cecil Beaton, Horst P. Horst, Lee Miller, David Bailey, Helmut Newton, but also many Italians such as Elisabetta Castiglioni and Ugo Mulas, who in agreement with the publisher’s choices defined the photographic aesthetics of the time.

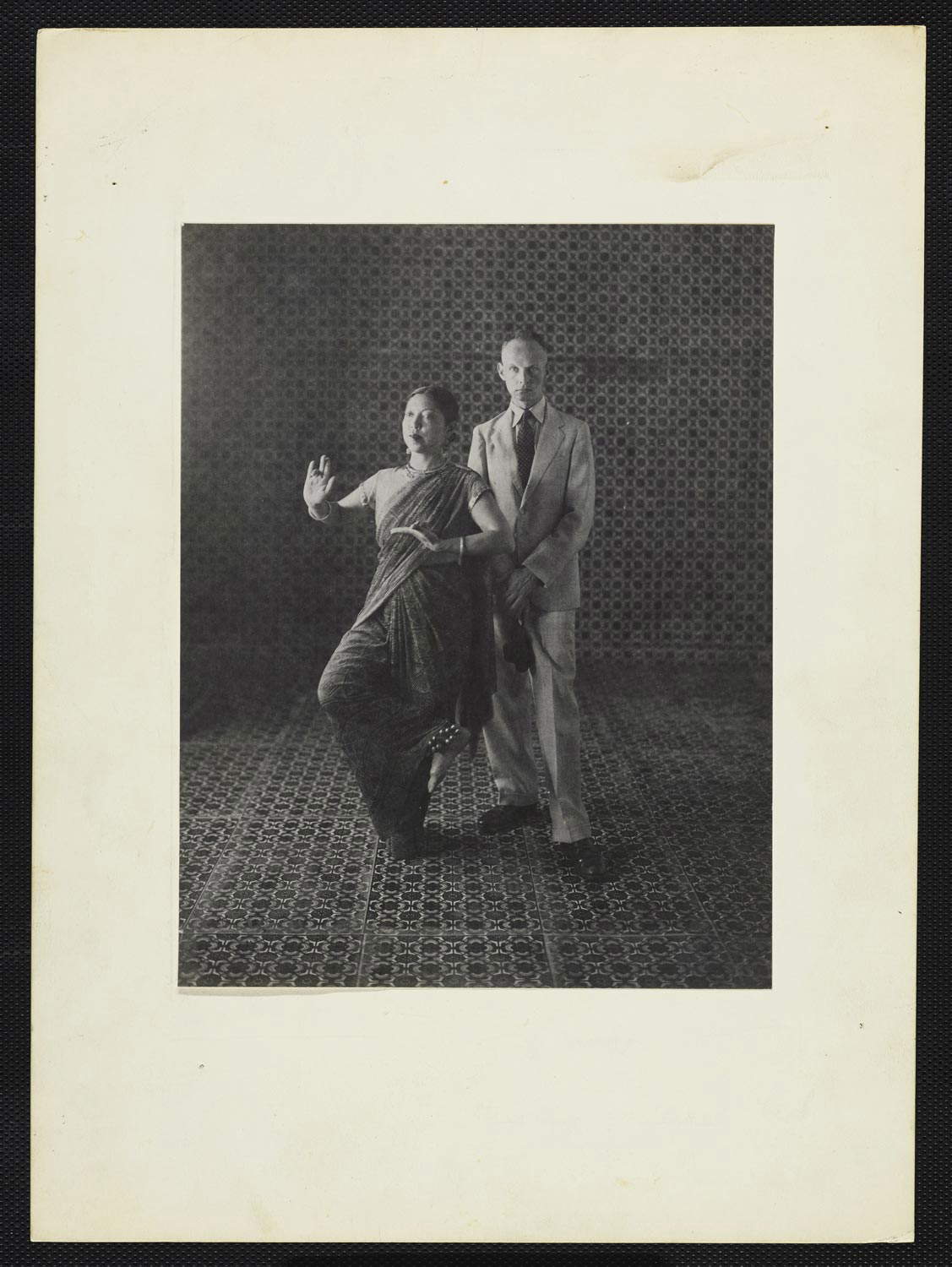

“These photographers owe much to the artistic directors of the iconic Condé Nast magazines, who were able not only to recognize their talent, but also to provide a showcase for their work long before they were acclaimed by the general public,” says François Pinault. The very role of the photographer changes over the years, thanks in part to Condé Nast editions: if before they were merely performers of the images accompanying the articles, over time they become artists, so recognizable that they themselves deserve to become the subject of the photos, as in Photographers Allan Arbus and Diane Arbus (1950) by Frances McLaughlin-Gill or Mr. and Mrs. Henri Cartier-Bresson (1946) by Irving Penn.

It is striking how many of these images are really icons of their time: they are the ones most used to narrate certain facts and characters and are so ingrained in our imagination that the continuing impression is that we have seen them before. We have never seen them, however, as in this exhibition where the originals of each photo are displayed. They are vintage prints, most often the first prints ever made for those images. And they carry with them all the marks of the era: hand-annotated captions, editor’s notes, crop marks to be operated on.

In the art that started the debate on technical reproducibility, we see here instead works that still defend their uniqueness, as works of art. Is journalism art? “Certainly,” answers Anna Wintour, and that is the spirit underlying this exhibition in which photos are removed from the editorial context for which they were designed, and become works of art in their own right. This certainly raises questions about the meaning of these images separated from the accompanying texts (or accompanying them ), and curators Matthieu Humery and Andrew Cowan say that “the answer is not obvious, because it invokes the qualities of photography as a representation of reality...but it also raises further questions about the autonomy of art.”

To further support this point of view, the historical images in the exhibition are in dialogue with the Chronorama Redux project with which the Pinault Foundation wanted to fund site-specific works by four artists Tarrah Krajnak, Eric N. Mack, Giulia Andreani and Daniel Spivakov as interludes that break into the chronological path of the main exhibition.

I felt like running inside these rooms so immense and full, like the protagonists of the famous scene in Bande à part (Jean-Luc Godard, 1964), and filling my eyes with the images that seem to flow as in the imaginary chronorama or as in those videos made in morphing that tell the passage of time in a few seconds. And then to go through it again and again at different speeds, stopping on individual photos and losing myself in the story they tell, dilating the instant of the single photograph. And then return to see it perhaps after a few days, when the memory of the images has settled, to discover stories that had escaped. And thus discover the deeper meaning of photography: stopping time, propping up the story on individual instants.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.