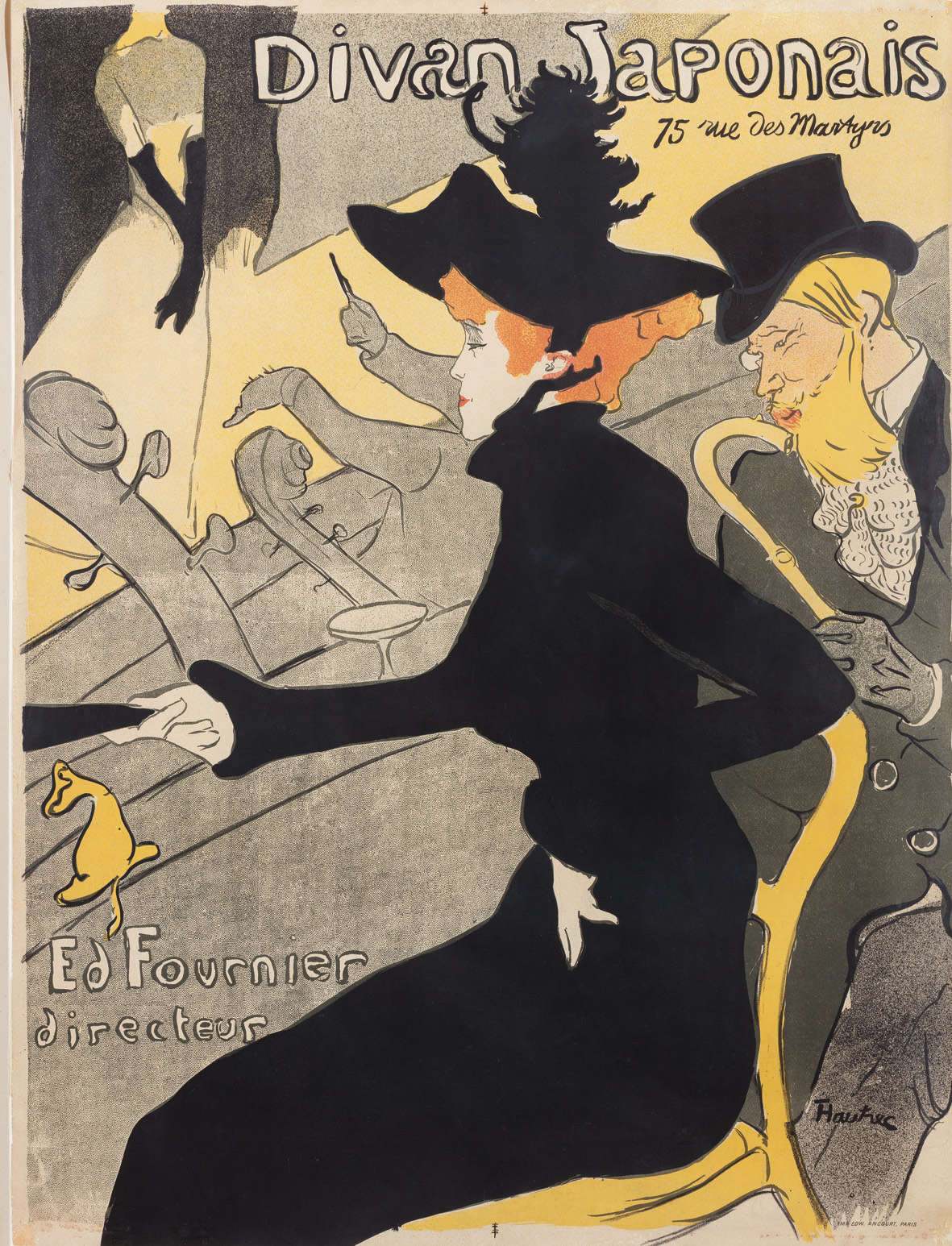

Ancient is the problem of the correct framing of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and his production: the long sequence of exhibitions that have been dedicated to him has looked, often almost exclusively, toward one part of his production, that of advertising graphics, and the public’s attention has almost always privileged the man rather than the artist. A long-standing problem, if one considers that as early as 1951, in Emporium, Giulia Veronesi wrote that the evaluation of Toulouse-Lautrec “is often invalidated and misdirected by several facts,” first and foremost “the fact that his work is so charged with social content, so pregnant with its own time, as to become in the highest degree symbolic,” and secondly the often having distinguished the painter from the graphic artist, having considered his exceptional, innovative poster art almost as a monad, detached from the rest of his production, and sometimes even from the context that produced it. Yet even Veronesi’s reading established a starting point that today appears almost restraining, namely, having based the beginning of the analysis of Toulouse-Lautrec’s production on a consideration by Theodor Däubler, who was convinced that the painter from Albi was the first expressionist in the history of art: Toulouse-Lautrec would thus have inaugurated, benefiting from Impressionist and Symbolist contributions, that painting “which in the object transfers subjective expression, makes it expressive by charging linear and color with expressive power.” Toulouse-Lautrec’s trajectory, in fact, was decidedly more nuanced: first, today it is difficult to call him a social painter. From certain themes he was completely detached (work in industries, for example, which was instead the overriding concern of so many of his contemporaries), and in his investigation, which, moreover, was not a translation of an interest in current events (if anything, it was in reality), he preferred a more intimate approach, one might say. Toulouse-Lautrec was not an artist who denounced, nor was he a kind of reporter with a paintbrush. Rather than unveiling and chronicling, he preferred a participatory account, from an involved person, a kind of description from the inside that, by virtue of its sincerity and also its variety, ended up taking on the traits of the symbol, became the allegory par excellence of that turn of the years that we define under the title of ’Belle Époque.

In Rovigo, Palazzo Roverella is dedicating an exhibition to the problem of Toulouse-Lautrec’s historical placement. Entitled simply Henri de Toulouse Lautrec. Paris 1881-1901, and curated by Fanny Girard, Jean-David Jumeau-Lafond and Francesco Parisi, the exhibition takes into consideration almost the entire artistic career of the painter, deliberately leaving in the background certain themes largely plumbed by previous exhibitions (the world of the circus, for example, or that of cabarets, which is well present but not only as theobject of the painter’s attentions, as much as above all as the fertile soil on which Toulouse-Lautrec cultivated his art, or even advertising graphics itself, to which a section is devoted in closing), and pouring its concentration above all on the context of the fin de siècle Paris, the Paris of artists, men of letters, cafés, and debates.

The public, among the rooms of Palazzo Roverella, will find above all an exhibition of paintings: it should be remarked, since in recent times we have been accustomed to exhibitions on Toulouse-Lautrec built mainly, and sometimes exclusively, with graphics. It is necessary, however, to know Toulouse-Lautrec’s painting if one wants to know Toulouse-Lautrec, for it is from painting that his modernity originates, it is from experiments in painting that the Toulouse-Lautrec best known to the general public was born, and the exhibition particularly insists, especially in the detailed catalog, on thestrongly experimental attitude of this artist who was born in the hills of Occitania and arrived in Paris at a very young age to study from the masters of the capital, beginning with that Léon Bonnat whose contribution on the formation of the young Toulouse-Lautrec was reread on the occasion of the exhibition in Rovigo: it is necessary “to rethink the established interpretation,” writes Francesco Parisi in the catalog, “that the period spent with the first master was more to be considered as a sterile passage, consisting of useless indoctrination and preparatory only to the later entry at Fernand Cormon’s atelier.”

It was in Bonnat’s atelier that Toulouse-Lautrec’s first interests in reality sprouted, which was initially expressed through a painting of somber tones, as seen in the only work in the exhibition referable to the early days of his apprenticeship with Bonnat, namely Champ de courses in which theartist depicts a horse race which, despite its high chronology, nevertheless gives evidence of the free and experimental attitude of a Toulouse-Lautrec then just in his twenties, but already projected toward cursive painting, toward unconventional color contrasts: one gets further evidence of this by looking at two later works, Allegorie, le printemps de la vie and Esquisse, peuplade primitive, tribu préhistorique. Two formative works, two works executed when Toulouse-Lautrec frequented Cormon’s workshop, two works of traditional subject matter, two works built around academically based compositions, yet imbued with the spontaneity that Cormon (present in the exhibition with a majestic portrait of a fisherman entitled Avant la pêche) advocated for his students. Two exercises, one might say, but which already hint at the artist’s future attitude, further discernible in the portrait of his father on horseback, which the audience encounters in the same room, and which foreshadows the later outcomes of his art.

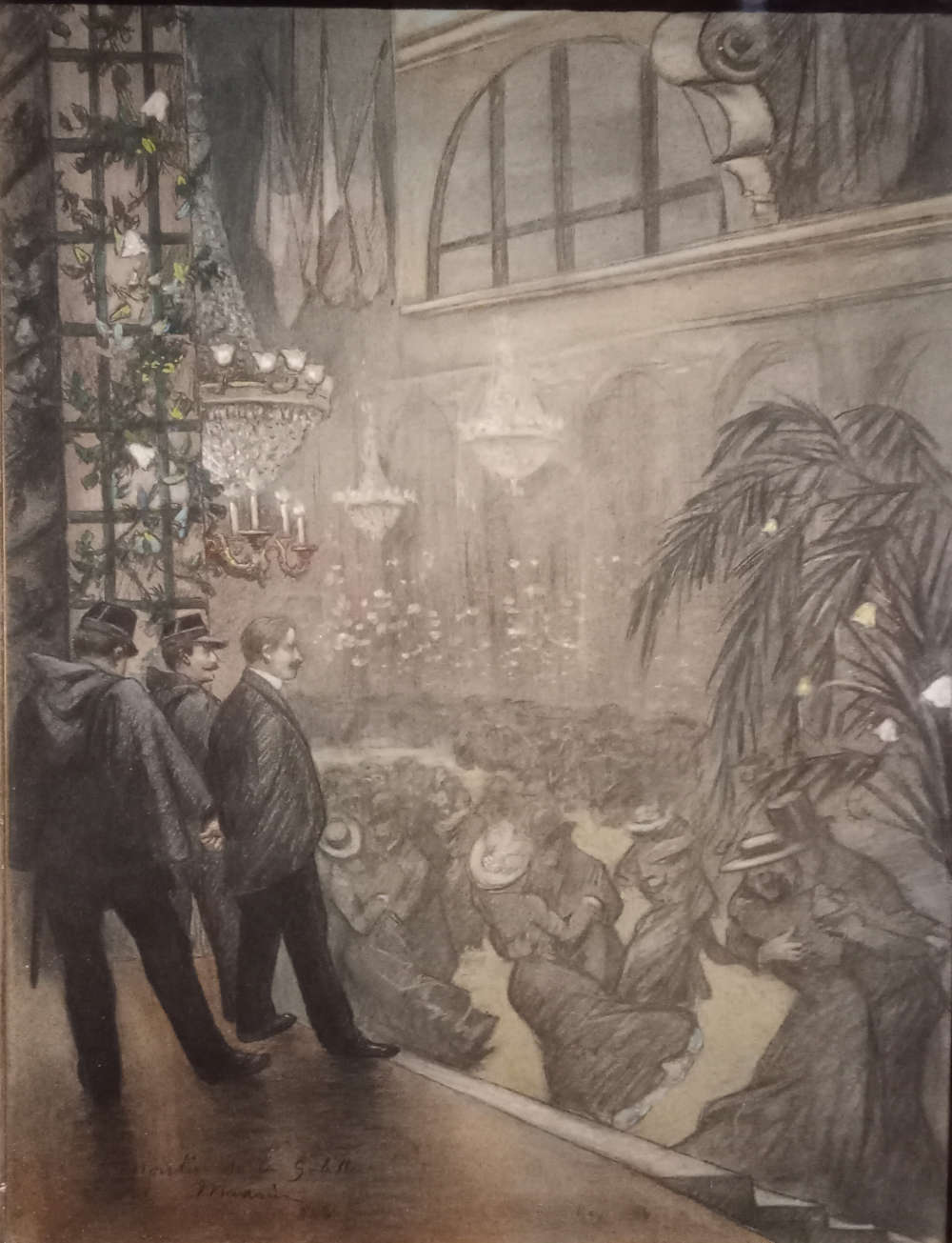

Continuing on the tour itinerary, the curators accompany the audience to late 19th-century Paris, first among café-concerts, cabarets and theaters with the section Sur la scène, a lively chapter of the exhibition functional to give an idea of the variety of the venues that animated the social and cultural life of the French capital, places of “democratization of amusements,” the room panels inform us, as the prosperous economic situation of Paris at the time allowed anyone to frequent the city’s many venues. It was this world that fascinated Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec: one catches an echo of it in front of paintings such as Louis Abel-Truchet’s Le Café-Concert or Charles Maurin’s Le Moulin de la Galette , chosen not only to transport visitors into the atmospheres of Parisian nightlife and to offer a tangible sign of the fascination this world exerted on artists (even on a young Pablo Picasso, incidentally: a pastel of his depicting the actress Yvette Guilbert, long Toulouse-Lautrec’s inspiration, on stage is on display), but also to give an account of the research, the ideas that circulated among the artists who frequented this much-mythologized milieu (look, in Maurin’s painting, at the contrast between the figures on the left observing the scene, defined, and the dance hall patrons dancing in the center, blurred, almost evanescent). Nor was there any shortage of those who sarcastically observed the nocturnal amusements of Montmartre: this is evidenced by a significant painting such as L’entrée au bal by Félicien Rops, an early work with which the artist, known for his ironic attitude, often bordering on fierce parody, intends to emphasize the marked social distance between the elegant ladies entering a dance hall and the boy dressed in rags observing them from outside. Other intentions, however, move the gaze of Toulouse-Lautrec, who, though close to Rops (especially in the 1990s), looks instead primarily to the Impressionists, notably Edgar Degas: the old Impressionist is present, in the opening section, with an Étude de danseuses that introduces the public to one of his favorite themes, that of dancing, and dialogues at a short distance with the first Toulouse-Lautrec masterpiece one encounters in the itinerary, the Danseuse assise sur un divan rose of 1884, on loan from the Dixon Gallery in Memphis, a canvas depicting a dancer sitting on a sofa, in a moment of rest, tired and perhaps a little bored. It is, of the works in the exhibition, perhaps the one closest to Degas, but for Toulouse-Lautrec the colleague is but a starting point for his investigation. Toulouse-Lautrec wants to capture the life of fin de siècle Paris, but with an attitude all his own. He is not a chronicler, and the role of psychoanalyst hardly fits him. He is more of an insider, we might say, who goes into industry to satisfy that “desire to ’capture,’” as Nicholas Zmelty effectively defines him in the catalog, “which passes through the multiplication of expressive means and stylistic developments in perfect harmony with his research [...]. Toulouse-Lautrec exploits all the means at his disposal to capture in his works the life he loves so much and of which he is both avid spectator and passionate actor. The spectacle, the nightlife, drunkenness, women: Toulouse-Lautrec is not content to observe things coldly, but lives them, confronts them in order to feel them better in the flesh, to appreciate them and be able to return them in the most authentic and concrete way possible.” Hence, the need to break free as quickly as possible from Degas in order to seek a personal, more synthetic way, as seen in the canvas Au bal masqué à l’Élyséand Montmartre, which we can imagine sketched directly on the spot, in front of a group of people in whom, Agnese Sferrazza speculates, we can perhaps recognize, because of the singular disguises, some members of the Société des Incohérents, to whom an entire section of the Rhodesian exhibition is dedicated, as will be seen later.

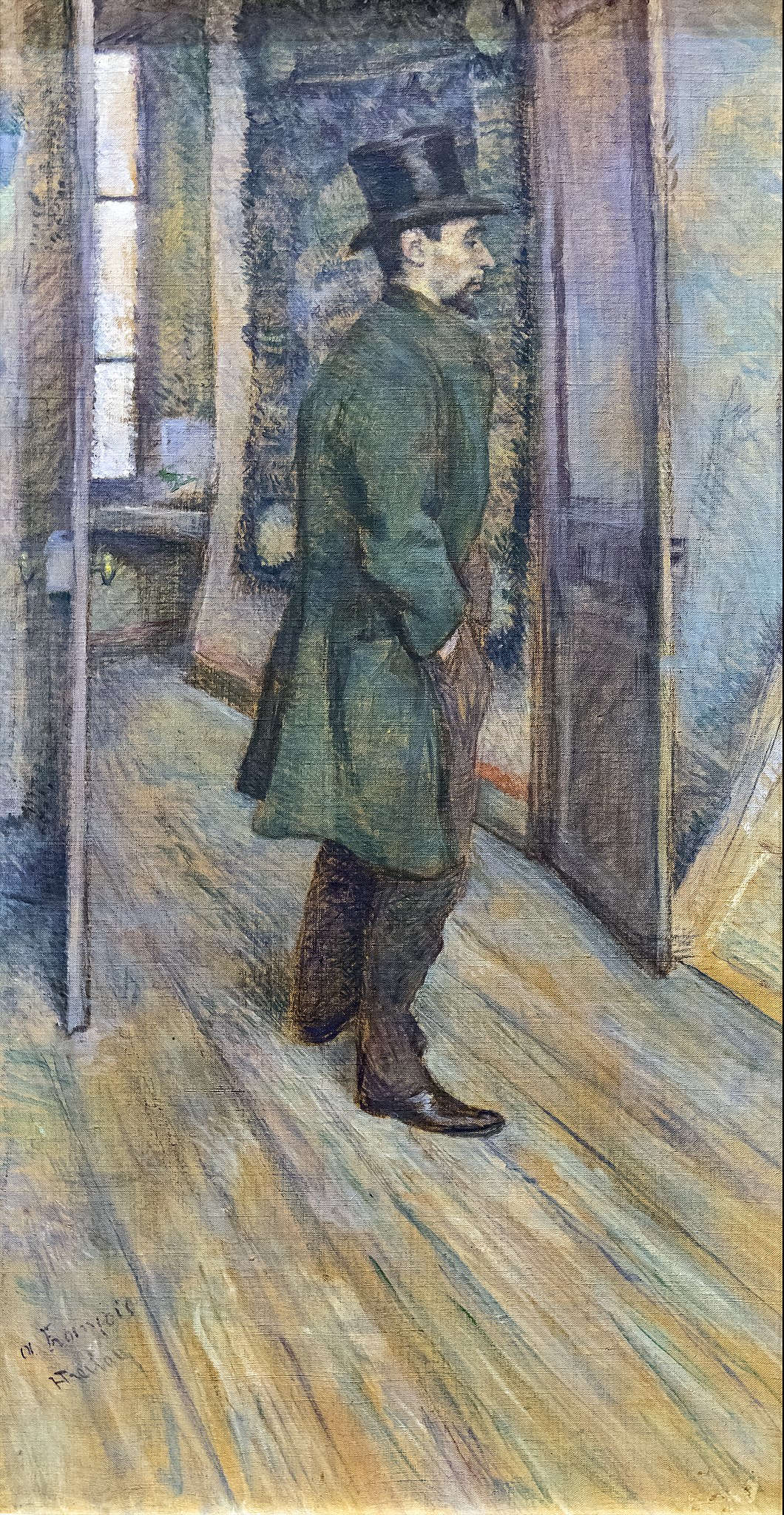

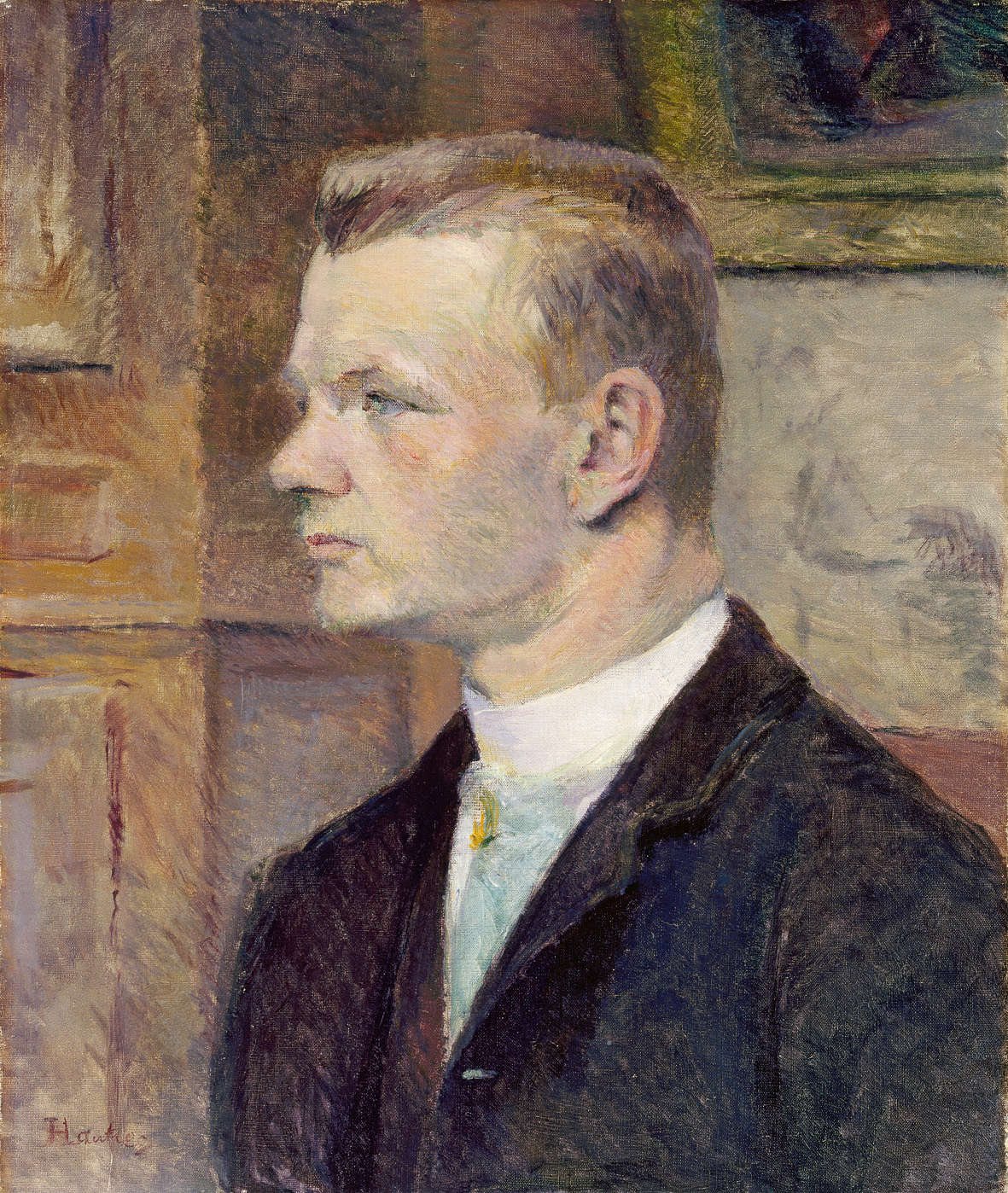

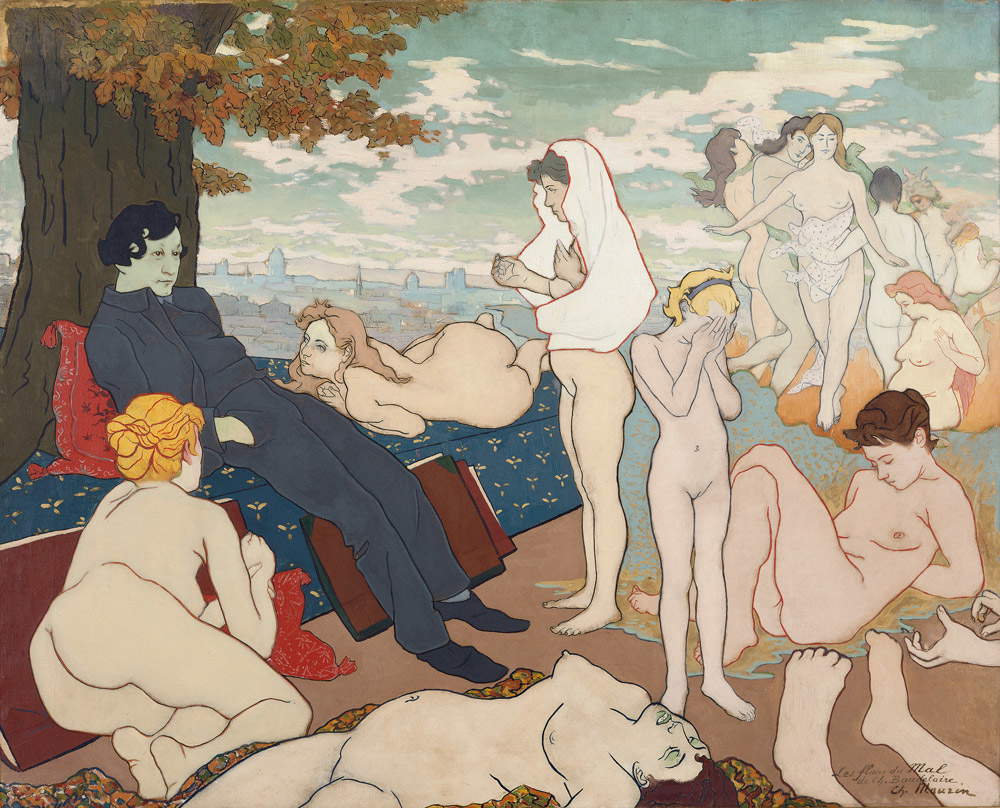

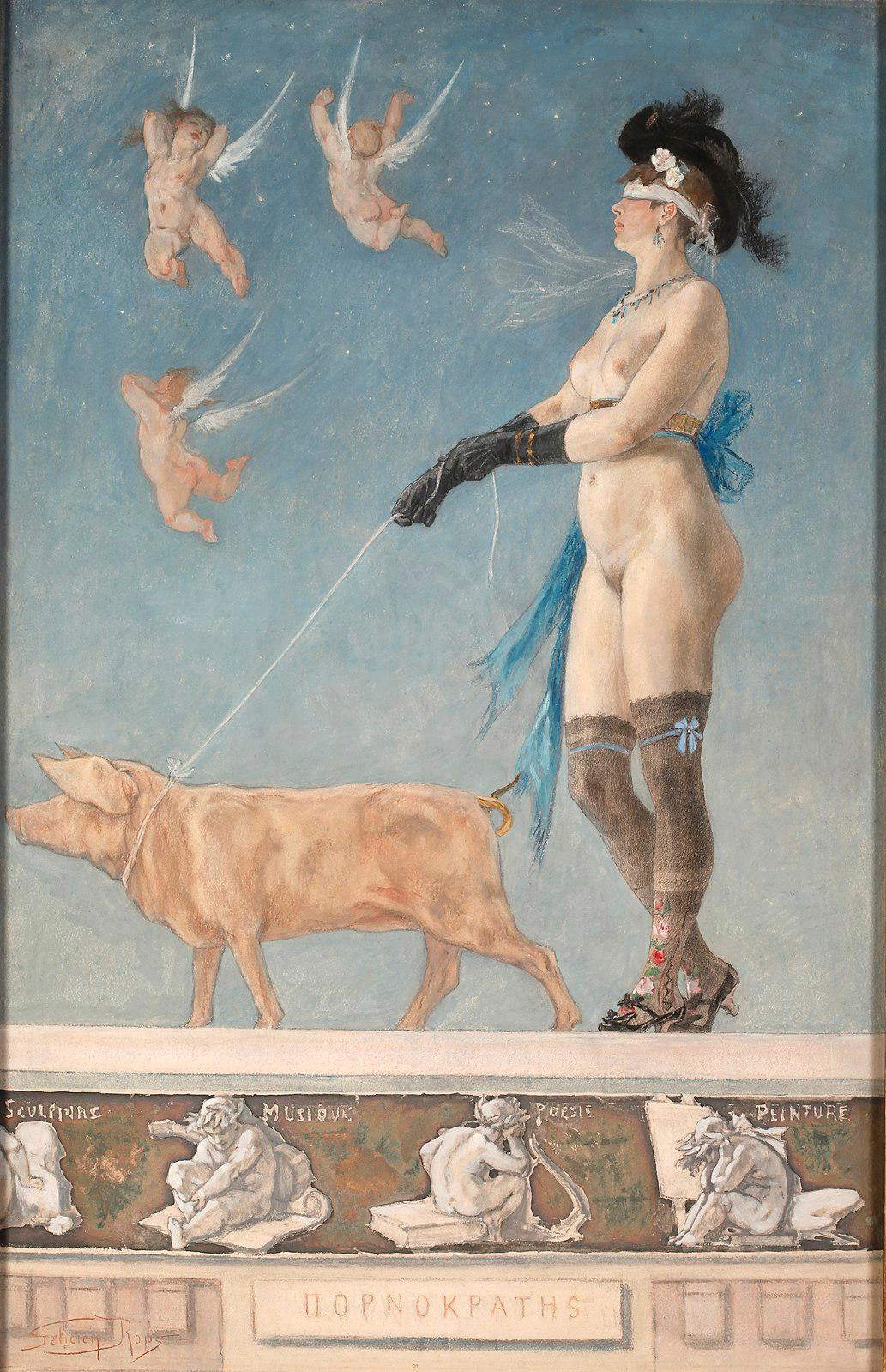

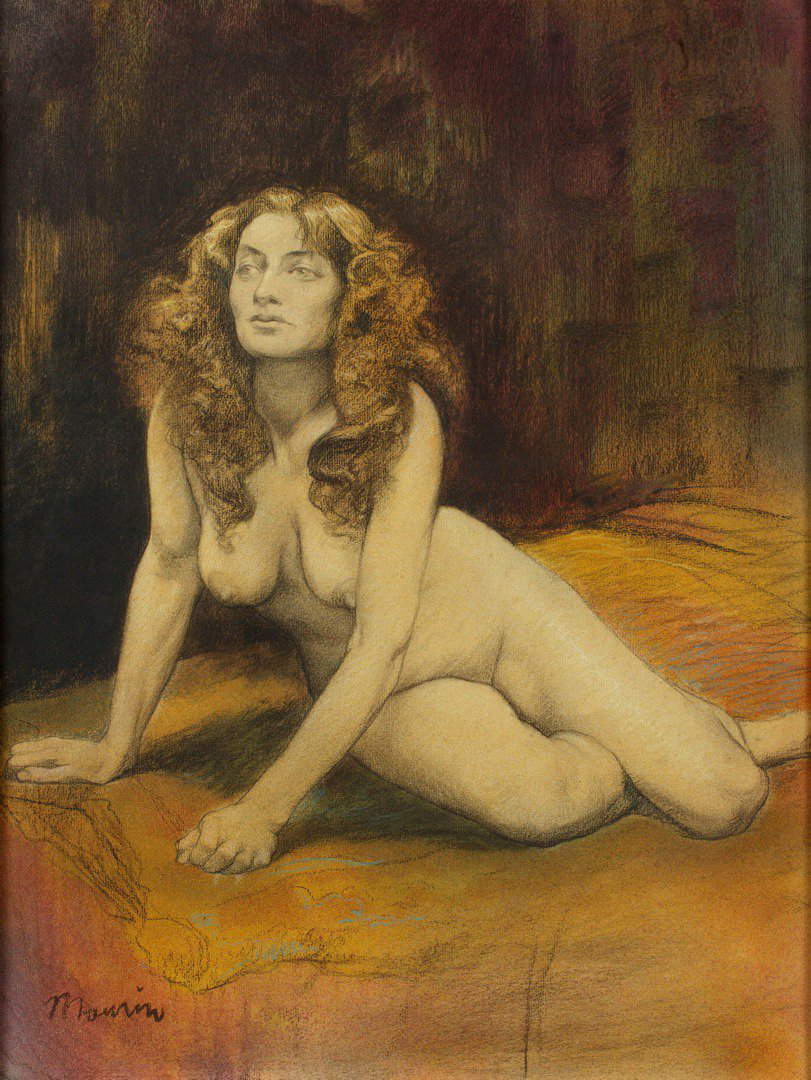

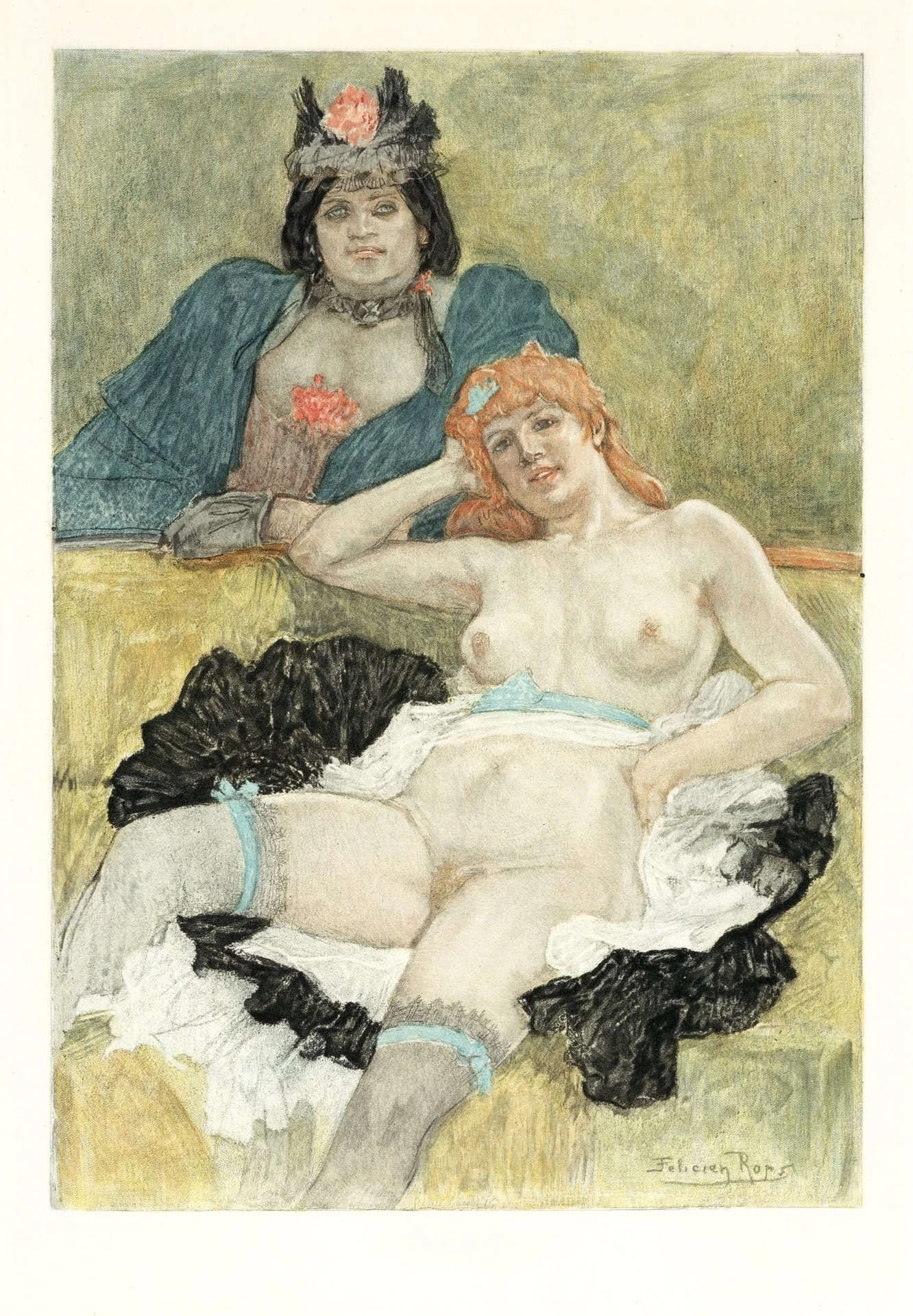

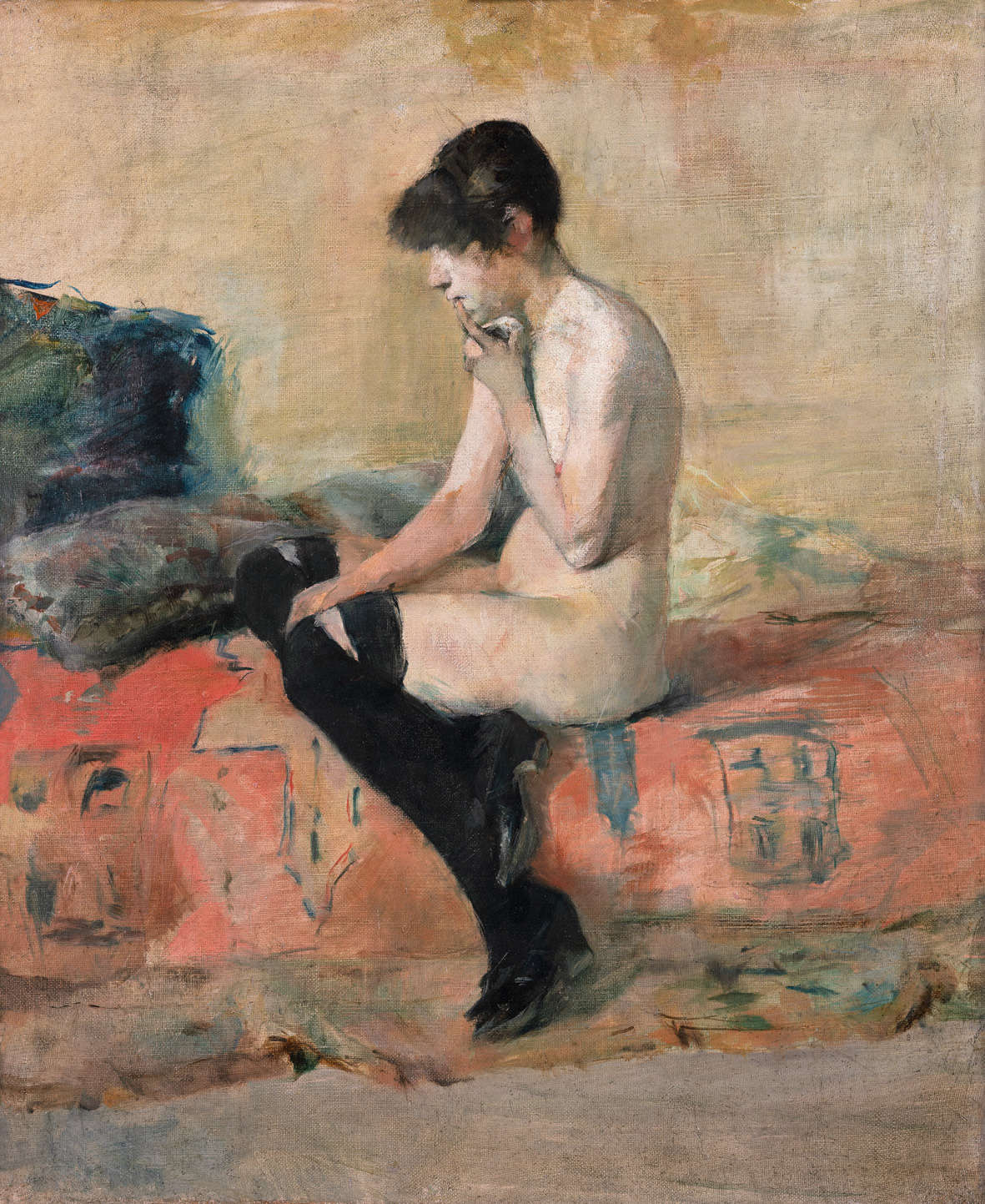

Paris is still the protagonist of the following sections, first with a focus entitled Paris, ville spectacle, where a group of paintings is gathered together that tell the city as a whole (they range from a large view of the Quai de Bercy by Albert Dubois-Pillet to women in front of the Moulin Rouge by Alfredo Müller of Livorno, from George Bottini’s window-shopping to engravings with views of Montmartre by Charles Maurin and Eugène Delâtre: there is also no shortage of ceramics from the Parisienne, a symbol of the elegance of that Parisian woman “heroicized by fashion and spirit,” writes curator Jumeau-Lafond), and then with the chapter Les peintres du petit boulevard, the name given to the group of artists who frequented Cormon’s atelier: these included, in addition to Toulouse-Lautrec, Émile Bernard, Louis Anquetin, François Gauzi, and even Vincent van Gogh (with respect to the Dutchman, the exhibition places great emphasis on his role as a lively and participatory cultural animator: audiences unfamiliar with this aspect of Van Gogh will be surprised; it’s just a pity that his works cannot be seen in Rovigo). It was Van Gogh himself who went out of his way to organize an exhibition of the Peintres du petit boulevard in 1887, and the suggestions that Van Gogh provided for Toulouse-Lautrec can be seen in the 1888 portrait of François Gauzi, arriving from the Musée des Augustins in Toulouse: the bold, strongly foreshortened vertical cut derives from Japanese prints, for which Van Gogh had already developed a strong passion, which he was able to pass on to his friend. The desire for modernity nurtured by the Peintres du petit boulevard was substantiated by a painting attentive to the life of the city, in all its aspects (the room panel refers to an 1883 Étude de nu by Toulouse-Lautrec, which the audience will see three rooms later: a royal nude that criticized the academic ones exhibited in the Salons), is also evidenced by the portrait of Carmen la rousse, Carmen “the redhead,” who in the verse of a panel in the Musée Toulouse-Lautrec in Albi, in which the girl is depicted in a traditional pose, is painted with her gaze downcast, with the idea of returning a portrait that conveys her state of mind, her inner condition. Toulouse-Lautrec’s cultural milieu then also animates the following section, The Literary Friends and Artists, a long list of portraits of the writers, artists, and personalities of the Montmartre of the time, and there are also portraits of Toulouse-Lautrec painted by his friends, as well as paintings that given account of those atmospheres, such as Charles Maurin’sAuror du rêve , a canvas inspired by Baudelaire’s Flowers of Evil , which the public finds in Veneto a few years after the Rose+Croix exhibition on mystical symbolism held between 2017 and 2018 at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice. It is difficult to give an account in a short space of the largest and most ramified section of the exhibition (thirty are the pieces that compose it), but some subsets can be found: there are, for example, the works from the colony of Spanish artists in Paris, to which, moreover, is dedicated an essay by Mario Finazzi in the catalog in which the points of tangency and possible absorptions of the Iberians of Montmartre by Toulouse-Lautrec are analyzed. There are the portraits of artists variously linked to the painter from Albi, also because of similarities in frequentations: so here, for example, is a portrait of Giovanni Boldini executed by Degas, present partly because Boldini, like Toulouse-Lautrec, nurtured a strong admiration for Degas, and partly because the artist’s contacts with the Italiens de Paris are well known. And then there are the works related to the Symbolist movement, such as the aforementioned painting by Charles Maurin, a masterpiece such as Pornocratès by Félicien Rops, Carlos Schwabe’s Les Litanies de Satan , sphinxes and assorted chimeras, or even the portrait of Paul Verlaine by Edmond Aman-Jean, or that of Joris-Karl Huysmans executed in ink on paper by Félix Vallotton: even if Toulouse-Lautrec did not feel Symbolist impulses, certain dark and oppressive overtones sometimes take hold of his work and allow his art to be read from a new, original perspective.

And to realize how these nuances could enter Toulouse-Lautrec’s art, one need only take a few steps further and enter the next section, Artificial Paradises, which revolves around the theme of absinthe addiction, capable of taking on the features of a social scourge in late 19th-century Paris: la Fée verte, the “green fairy,” as this alcohol was nicknamed because of its color, was a widespread fashion, became something of a symbol of bohemian life, and for many turned into a devastating disease (Verlaine’s alcoholism, for example, is well known), so much so that in 1914 absinthe was declared illegal. Welcoming the public into the room is a painting by Albert Maignan depicting a personification of absinthe: the Muse verte is a comely fairy, wrapped in a green tunic, who reaches behind the drinker’s back and attaches herself to his head, causing him that state of intoxication sought by consumers of the strong drink. Absinthe was drunk diluted with water and a sugar cube, which dripped into the glass through a special pierced spoon that was placed on it.Around the table that evokes the ritual of absinthe consumption, placed in the center of the room, one can admire the works featuring absinthe drinkers. One of the pinnacles of the entire exhibition is the double confrontation between Toulouse-Lautrec(À Grenelle: L’attente and La buveuse) and Rops(Le Quatrième verre de cognac and La buveuse d’absinthe), one of the most interesting subjects of the Rovigo exhibition: “Lautrec,” Parisi explains, "produced several works on the theme of female alcoholism [...]. If Rops’ Buveuse showed traces of intoxication and a satanic look, the interpretation given by Lautrec turned out to focus more on the ’bestial’ character of the woman than on the ’transcendental’ and culturally decadent aspects. While admiring the Ropsian talent, as seems explicitly evident from some of the works, Lautrec was nevertheless far from the Belgian artist’s demonic depiction of woman, even when placed in contexts more congenial to him." In Rops’s two works, the artist’s gaze reaches a savagery that is entirely unknown to Toulouse-Lautrec, an artist with a more melancholy temperament: À Grenelle, a work presumably inspired by a ballad of the same name by the chansonnier Aristide Bruant (the subject, moreover, of some of the artist’s celebrated prints), is a work that captures the loneliness, the malaise of the frequenter of a bar who submerges her past in the glass of absinthe placed before her, and from which she even looks away. There are also paintings that, with a more realistic air, offer insight into the consequences caused by absinthe: This is the case, for example, with Gustave Bourgain’s Buveur d’absinthe , a pitiless portrait of a drinker with a vacant gaze and a scruffy air in front of the glass of the green alcoholic, or the melancholy Les incompris, a 1904 masterpiece by André Devambez, in which one of the protagonists seated around the table, the one on the right (perhaps Paul Verlaine), appears at the mercy of the effects of alcohol. A melancholic painting, because although it depicts some artists and intellectuals arguing around a table, and thus apparently a work that effectively restores the climate of those years, it appears to us to be crude in restoring these characters ahead in years who still have not resigned themselves to the passage of time, a circumstance of which the woman clutching, almost in a fit of rage, the magazine L’Art is probably aware. We know her: she is the painter Victorine Meurent, that is, the woman who, forty years earlier, had been the model for Édouard Manet’sOlympia : that naked, fragrant, uninhibited young woman has become the sullen old woman in Devambez’s painting. A different drama, on the other hand, is that of Eugène Grasset’s Vitrioleuse , a portrait of a disturbing-looking woman holding a bowl of vitriol, another allusion, not even too veiled, to the effects of absinthe.

Here then, in the next room, is the revelation of the exhibition, namely the section devoted to Les arts incohérents, the singular movement led by Jules Lévy, which had fallen into oblivion, and only re-emerged to critical attention in 2018, when several works by artists belonging to the group were rediscovered, thanks to the work of gallerist Johann Naldi (also author of the catalog essay devoted to this very particular movement): some of these works, seventeen in all, were moreover declared Trésor National by France’s Ministry of Culture. Until 2018, it was thought that all the works of the “incoherent” artists had been lost: in Rovigo it is therefore possible to admire a selection of works by this mishmash of characters that included professional and amateur painters, writers, journalists, draftsmen, and that anticipated in some ways Dadaism, Surrealism and much twentieth-century art with the aim, Naldi summarizes, of “challenging through laughter - but not only - the seriousness of the art world.” Works that, it is useful to point out, for the first time in history come out of France: another gem, then, of this exhibition. Here then is the first monochrome painting in the history of art known so far, Paul Bilhaud’s Combat de nègres pendant la nuit , an all-black canvas accompanied by an ironic title to mock the public, and then again a proto-readymade, a green curtain entitled Des souteneurs encore dans la force de l’ âge et le ventre dans l’herbe, a painting-object by Gieffe (pseudonym of François Jules Foloppe) that gives substance to a fable by La Fontaine, and posters and catalogs of the exhibitions that the incoherents, in their short period of activity, managed to organize in Paris could not be missed either. Toulouse-Lautrec also frequented this group and helped it set up a number of exhibitions, without calculating the fact that he was among the artists who benefited from the desecratory, free and rebellious climate that was in place whenever Jules Lévy and co. architected their exhibitions.

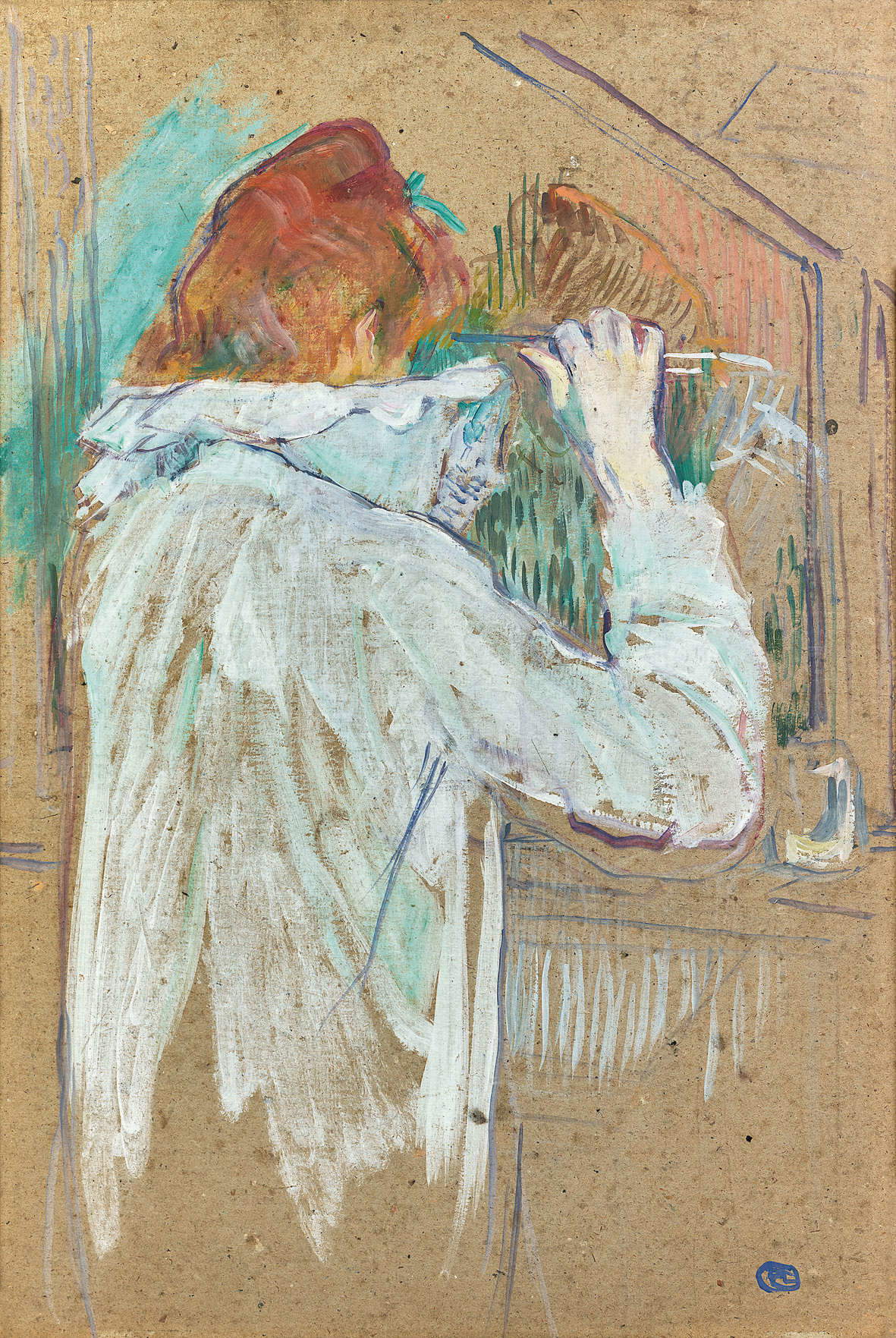

More grim and resigned, however, is the air that pervades the next room, dedicated to Elles, the prostitutes depicted by Toulouse-Lautrec in a well-known portfolio of lithographs (some examples are in the exhibition) that had little commercial success but raised discussion, beginning with its publication in 1891: the section, while not the most original in the exhibition (the theme of meretriciousness in Toulouse-Lautrec is among the most critically examined), nonetheless offers a more comprehensive view of the theme of prostitution in the art of the time, establishing a new parallel with the art of Rops, who in Les Deux amies approaches thesubject from a different perspective, emphasizing "the devilishallure of the temptress woman, rather than the more realistic aspect of the female condition" (so Agnese Sferrazza), while Albigese, with his Études de nu (one of which compared with a canvas by Giovanni Boldini: same pose, opposite results), in addition to polemicizing the academic nude by offering a simple, sober representation of women, devoid of any hint of eroticism, manages to enter the daily life of his models, overcoming any stereotype but at the same time avoiding pietism and pity. Toulouse-Lautrec’s was simply a search for truth. Here then are frank and natural portraits, such as that of Mademoiselle Lucie Bellanger, or the even more eloquent one known as Femme se frisant, a snapshot of a girl combing her hair in front of a mirror. Works that are presented with that immediacy and spontaneity that Toulouse-Lautrec had arrived at after years of intense experimentation, including technical experimentation, arriving at a painting made of oil colors dissolved in turpentine and then spread on cardboard: “the raw cardboard,” explains Fanny Girard in her essay entirely centered on Toulouse-Lautrec’s technical innovations, “absorbs the essence of turpentine, leaving only the pigment to appear, which takes on anopacity reminiscent of pastel,” avoids the glossy effect that the artist shunned, and gives the whole the sketchy appearance that, on the contrary, Toulouse-Lautrec sought.

![Félicien Rops, La buveuse d'absinthe (1876 [1905 edition]; héliogravure, 240 x 160 mm; Rome, Private Collection) Félicien Rops, La buveuse d'absinthe (1876 [1905 edition]; héliogravure, 240 x 160 mm; Rome, Private Collection)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2024/2586/felicien-rops-la-buveuse-d-absinthe.jpg)

We descend to the lower floor for the last three rooms of the exhibition: one of these is entirely devoted to the Chat Noir cabaret, perhaps the most daring of cafés in late 19th-century Paris. Here then are paintings, drawings, magazines (the Chat Noir had one of its own), poems, even signs to evoke the extraordinary season of the nonconformist cabaret founded by Rodolphe Salis, the first café to introduce a piano, a place ofmeeting place for artists, writers and poets who gathered to discuss, argue, sing, recite verses, improvise recitations, a joyous meeting point but also a “workshop of Decadentism and Symbolism” as Jumeau-Lafond well reconstructs: the exhibition is able to offer a lively and valuable reconstruction of what the Chat Noir must have been. The conclusion of the exhibition is entrusted to the two more conventional rooms, those on Toulouse-Lautrec’s posters and graphics, to close the discussion with the best known and most innovative portion of his production.

In one of his 1899 articles, Julius Meier-Gräfe wrote that, with Toulouse-Lautrec, a “great art,” that of the Monets, Renoirs, Pissarro, and Degas, was “on its way to the grave.” it was certainly too early to celebrate the funeral of Impressionism, which would still have something to say in the early part of the twentieth century, but it can nonetheless be said that already at those heights the German critic had sensed the scope of Toulouse-Lautrec’s art. An art that today, in Rovigo, we reread in the framework of a broader context, stripped of the mythographies that have accompanied it in most of the exhibitions that have been dedicated to it, also because of the ease with which it is possible to organize exhibitions about him (the advantage of lithography, and in general of printed reproduction, lies in the fact that ideas circulate more, and the disadvantage, today, is that the reproduced image lends itself to rawness and pre-packaged exhibitions that besides the artist’s big name have little to give the public).

“Finally,” one might say at the end of the Rovigo exhibition: an exhibition in which the context in which the artist worked is reconstructed with lenticular precision and with surprising novelties (the hall of the incohérents alone is worth the trip to the Veneto), an exhibition that does not get lost in anecdotes about the artist or in biographism, an exhibition that brings out clearly the spirit of the artist. A spirit that corresponds little to the soul of the supposed celebrator of the Belle Époque that Toulouse-Lautrec never was, much less was he a kind of activist who revealed the social conditions of the categories that populated his works, beginning with the harlots, who become the privileged subject not on the basis of ’a desire to denounce but, more simply, partly because they were frequent subjects in the art of the time, and partly because they were familiar to him. A spirit certainly more restless and decadent than the one sung by the vulgate. The exhibition gives a more complete reading of it, certainly closer to what must have been the real temperament of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. A Toulouse-Lautrec we prefer. Lost and found.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.