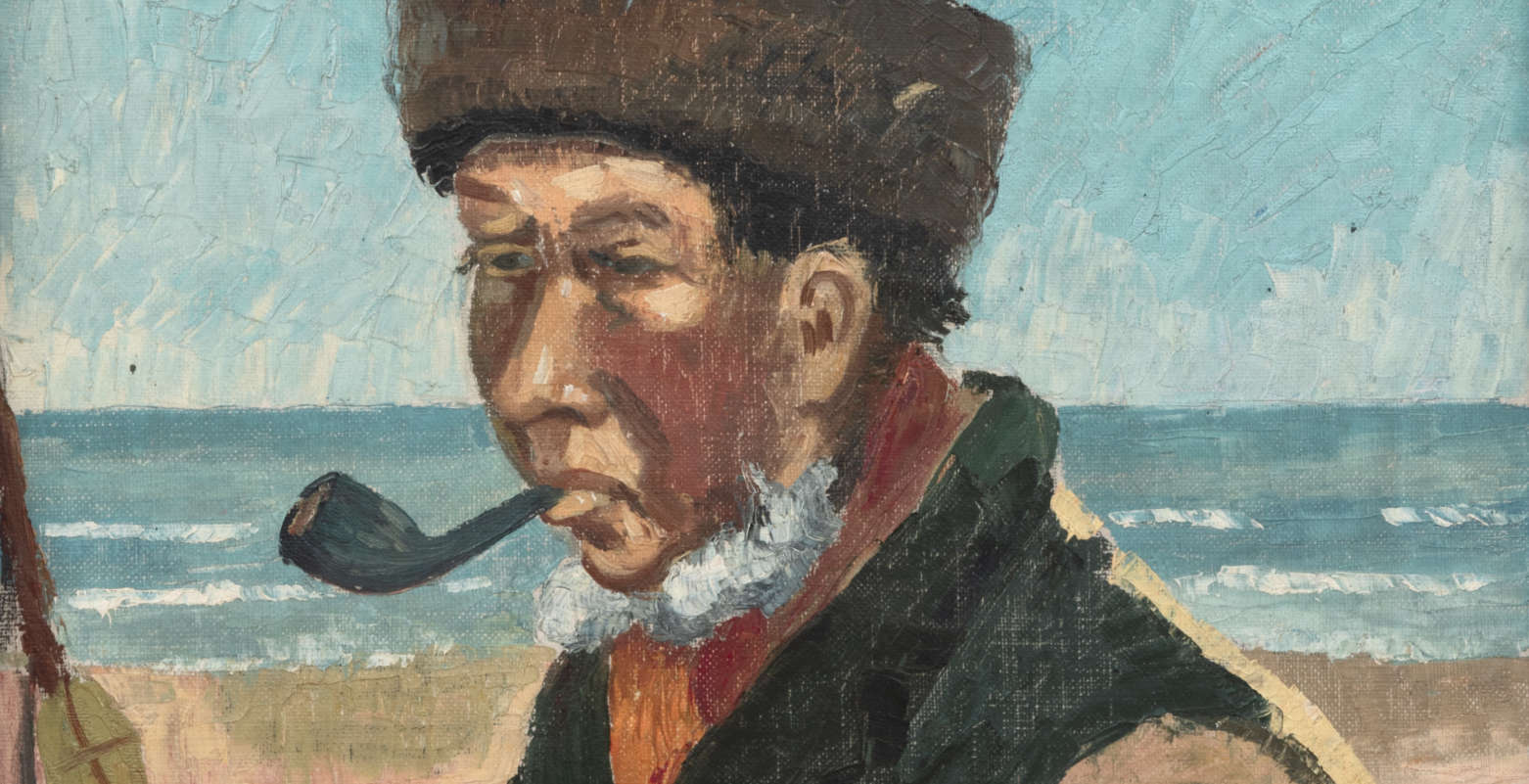

Is there a new Van Gogh out there? No: the rediscovered fisherman is the work of an unknown Dane.

Is there a new Vincent van Gogh work in circulation? No: the fisherman’s portrait for which New York-based LMI Group International sought authentication from the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam received, as was largely predictable, a flat “no” from the Dutch institution. There is no way that work could be authentic: the lines have nothing to do with Van Gogh’s, the colors are very different from those the Dutch painter chose, the impasto very far from that of the artist. The museum had already expressed its opinion in 2019, and in an email sent to Art Dependence magazine it reiterated the opinion: a resounding rejection.

The company believed in it, and had had the painting subjected to numerous analyses, according to which all materials were compatible with a 19th-century placement of the work: organic components had been analyzed (with the conclusion that the egg-white finish was compatible with the protections Van Gogh gave to the paintings once they were finished), the letters of the inscription “Elimar” that appears in the painting (interpreted as the name of the fisherman) had themselves been investigated, finding similarities with Van Gogh’s handwriting, and the DNA of a red hair “trapped” between the brushstrokes had even been analyzed. And last week, the company had issued a statement with the bombastic title, “Van Gogh painting discovered.” The company even published a 458-page report on its website to corroborate the alleged autography: analysis and studies on the painting cost a total of close to $30,000. None of the evidence provided appears decisive, however. In LMI’s view, Elimar would nonetheless be “an emotionally rich and deeply personal work created during the last and tumultuous chapter of van Gogh’s life,” linked to a Hans Christian Andersen short story, the Elimar from The Two Baronesses. More: it would be, according to the company, a self-portrait in which Van Gogh “reimagines himself as an older, wiser man, depicted against the clear sky and calm expanse of water, evoking his personal interest in life at sea.” The analysis on the painting “provides new insight into van Gogh’s oeuvre, particularly in terms of his practice of reinterpreting works by other artists,” said Maxwell L. Anderson, chief operating officer of LMI Group. “This moving likeness embodies van Gogh’s recurring theme of redemption, a concept often discussed in his letters and art. Through Elimar, van Gogh creates a form of spiritual self-portrait, allowing viewers to see the painter as he wished to be remembered.” According to LMI, the painting would have been made by Van Gogh while he was in the sanatorium of Saint-Paul-de-Masole in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence: to wit, the same period when he painted The Starry Night and other masterpieces. Of significantly higher quality, even to a layman, than the alleged Elimar.

Too bad then that against the company’s opinion came the more authoritative opinion of the Van Gogh Museum, for which, as mentioned, there is no possibility that the painting could be by Van Gogh (LMI has, however, let it be known that it wrote an e-mail to the museum protesting its methods: the rejection would come within hours and without even viewing the work live). At the moment, the most influential scholar to have spoken publicly, Wouter van der Veen, a Van Gogh expert and longtime scientific director of the Institut Van Gogh in Auvers-sur-Oise, has branded the whole thing a “farce,” believing that attributing this painting to Van Gogh is not simply a “mistake” but a “disgrace.” moreover, the team assembled by LMI (which does not include Van Gogh experts recognized by the academic community: the only one who has a vague connection with Van Gogh is an artist who has written a popular book on the Dutch painter), according to Van der Veen, did not even consider the fact that “Elimar” is not the name of the character depicted, but the artist’s signature.

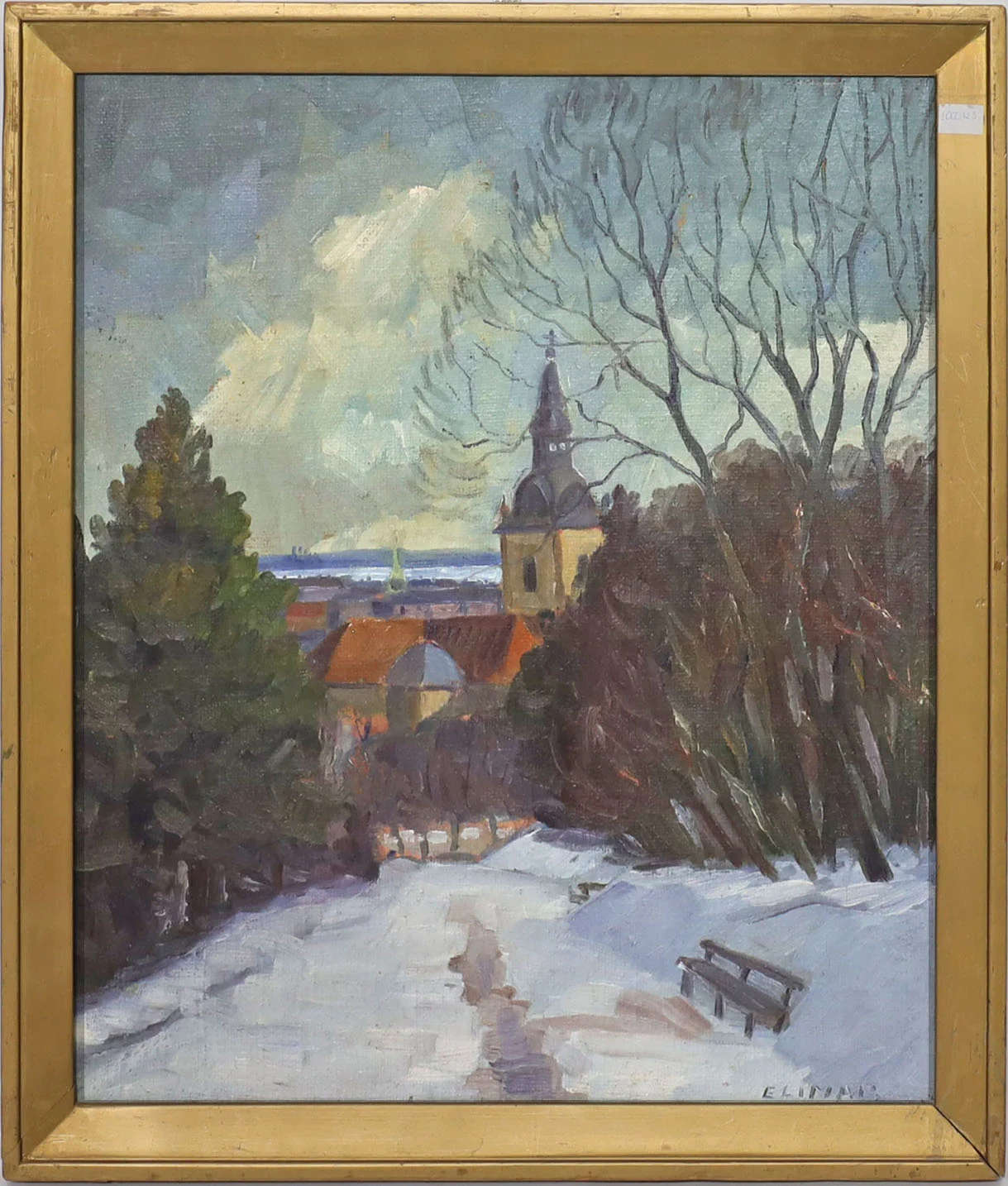

On this last point, providing clarification comes art historian Victor Rafael Veronesi, who considers the painting “an extremely naive work that many, even those not in the field, had guessed could not be by the tormented Dutch painter.” Elimar, Veronesi explains, is in fact the name of Henning Elimar, a Danish painter born in 1928 "whose art is reminiscent of that of the artist author of Starry Night perhaps because of its spontaneity and somewhat kitschy ’anti-academism.’" According to the scholar, the company has also come quite close to unraveling the alleged mystery of the fisherman, since the report traces the work’s first source, namely a painting by Danish artist Michael Ancher depicting The Sailor Nils Gaihede Repairing a Net, which was sold on the international market in 2023 (and a drawing of which was also sold in Sweden last year). Of this drawing, "the head proposed as a work by the Sunflower artist was supposed to be a derivation, according to LMI international, and the latter gave an account of it in its condition report of more than 400 pages, but failed to clearly confirm that it could be an image known to the Dutchman."

On the contrary, “Elimar” is the signature of Henning Elimar, who signed many of his works and landscapes with his surname, with the same capital letters as in the painting proposed as a Van Gogh by LMI (“and you wouldn’t need,” Veronesi adds, “photo editing programs to see that, or a study to the degree of the slants of who knows what letters”). Moreover, “moreover, the features of the painted subject are as angular as those of the twentieth-century Die Brücke movement. Finally, the canvas and frame, seen from the back (if not re-lined and replaced) looked rather twentieth-century and not nineteenth-century. Little use, moreover, was therefore, given the ambitious proposal, for a study that failed to fully reconstruct the remote provenance for the work that seems on the one hand to have emerged from nowhere and on the other hand was intended to be brought back to the 1880s-90s or so.” Pleonastic then are all the technical analyses to which the painting has been subjected. “Wanting to draw the sums,” Veronesi concludes, "it can be said without any doubt that the news had an undoubtedly worldwide echo and gave visibility to the company that was carrying the attribution. Of course, one would have to ask whether this visibility is positive or negative, in the face of a search that seems to be conducted a priori against a reasoned response already provided in 2018 by the Van Gogh Museum. It is undoubtedly everyone’s dream to find a masterpiece by a schoolmaster and pay a few tens of dollars or euros for it in a flea market, or to rediscover by chance in a bric-à-brac a painting by a great master, but this good fortune, as much as it is possible, is very rarely had. At the very least, a masterpiece is apprehended immediately, immediately as such, and does not lead even the non-professional to realize that something is wrong with an attribution that seems ’inflated,’ stunted, out of place for images that manifest something else entirely."

LMI has already let it be known, writing an email to ARTnews magazine, that they feel they can rule out attribution to Henning Elimar on the grounds that the palette, they say, is nineteenth-century and not twentieth-century, in addition to “other bases for its authentication.” But without letting them know what basis (probably those contained in the report, however, not decisive). LMI purchased the painting in 2019, for an undisclosed sum, from an anonymous collector, who had bought the work for less than $50 after finding it at a flea market in Minnesota. Of course, everyone would have loved to tell the story of a Van Gogh paid less than dinner at a restaurant, but it didn’t happen that way. And one can only agree with the comment of Bendor Grosvenor, who wrote on BlueSky, “The mystery to me is why this story, and others like it, get so much worldwide attention when they failed in the beginning.”

|

| Is there a new Van Gogh out there? No: the rediscovered fisherman is the work of an unknown Dane. |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.