Did Caravaggio fight as a soldier in Hungary before going to Rome? Here's what we know

There is a gap of at least four years in the life of Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi; Milan, 1571 - Porto Ercole, 1610): we do not know where he was and what he did between the last months of 1592 (the year to which the last known evidence of his presence in Lombardy dates) and 1596, when he is instead documented in Rome. In recent years a peculiar hypothesis has begun to circulate, according to which Caravaggio fought as a soldier during this time. It is an idea that has been, to some extent, cleared by the popular popularizer Alberto Angela, who made it known through an interview he gave to the TV magazine , Sorrisi & Canzoni, where, however, the hypothesis was presented in very romanticized tones.

“There are times when no one knew where he was,” Angela declared. “And perhaps one of these is allorigin to his violent nature: it seems he went for a few years to fight as a mercenary, developing on his return the ’Rambo syndrome,’ that of veterans who can no longer fit into society. This would also explain his skill with weapons.” Rambo syndromes aside, this is an idea that Caravaggio scholars are working on: art historian and Caravaggio specialist Rossella Vodret, among others, discusses it in one of her latest works, the book Luoghi e misteri di Caravaggio written together with Paolo Jorio and published by Cairo in 2018 (a review of the volume, written by Michele Cuppone, can be found on Finestre sull’Arte ).

|

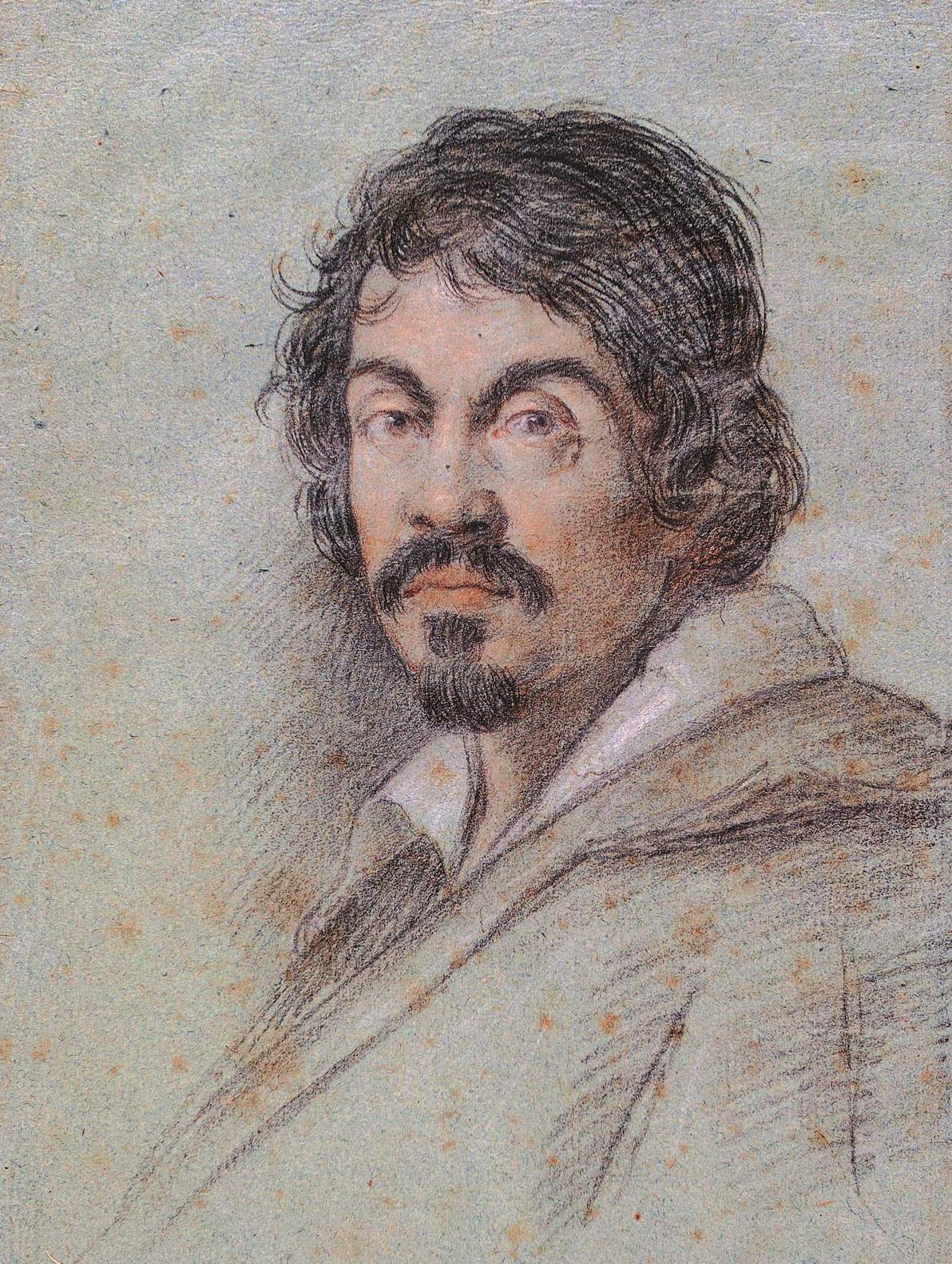

| Ottavio Leoni, Portrait of Caravaggio (1615-1620; black charcoal and pastels on blue paper, 234 x 163 mm; Florence, Biblioteca Marucelliana) |

The book states that Caravaggio appeared in Rome suddenly, on a Lenten day between March and April, “after four long years of absolute silence.” What had the artist been doing between 1592 and 1596? Perhaps a study trip between Lombardy and Veneto to learn about the art of the Lombard and Venetian masters (such as Moretto, Moroni, Savoldo, the Campi brothers, and the Venetians, from Titian to Tintoretto), or likely to have been in prison. “Among the conjectures formulated,” we read in Vodret and Jorio’s book, “the most disturbing was that he had served as a soldier in the Hungarian War, fought in those same years, which pitted the Austrian Empire against the Turks. His bad temper, his familiarity with weapons, especially with swords and daggers, which he knew how to use well and which would become one of the most frequent causes of his trouble with the law, by no means made it a possibility to be discarded. On the contrary.” To get more elucidation on the subject, we reached out to Rossella Vodret herself, who also collaborated as a scientific consultant for the program Stanotte con Caravaggio, Alberto Angela’s special dedicated to Michelangelo Merisi.

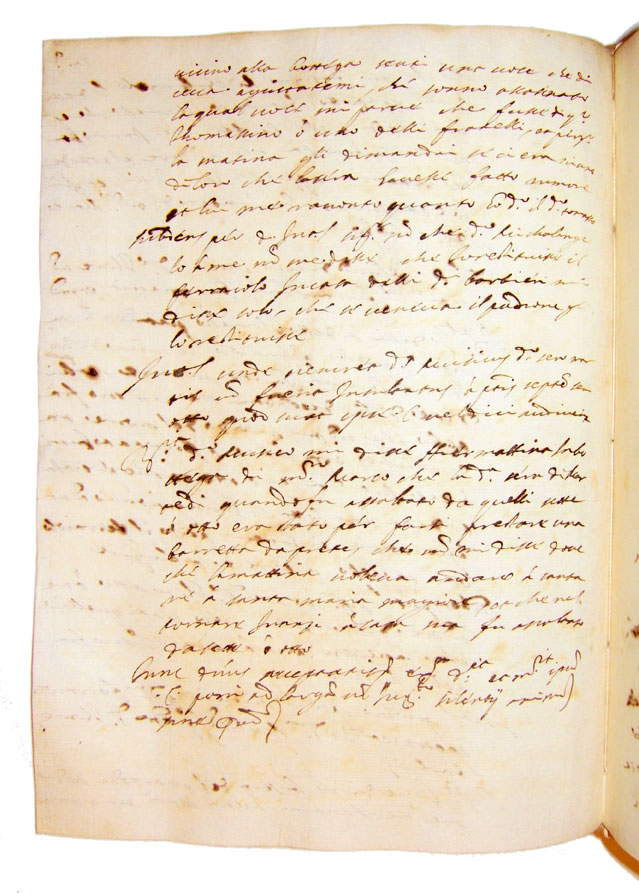

In the meantime, Vodret clarified that, of course, if “Rambo syndromes” are possibly mentioned in the program, they will be free interpretations by Alberto Angela, since the texts provided to Rai were limited to summarizing the hypothesis of the Caravaggio soldier in Hungary without, however, venturing into hasty conclusions or using inappropriate expressions. In any case, the scholar explained to us, it is a hypothesis launched years ago by art historian Luigi Spezzaferro (Rome, 1942 - 2006) and “back under the lens now that, after the studies published in 2011, these four years, between 1592 and 1596, during which Caravaggio’s whereabouts are unknown: he could have been in jail in Milan, he could have been traveling to Venice.” In fact, in 2011 a hitherto unpublished document, discovered in the State Archives in Rome by scholar Francesca Curti, was published, shifting Caravaggio’s arrival in Rome to 1596, and not at the end of 1592 as previously thought.

|

| The deposition of barber Pietro Paolo Pellegrini, the document discovered in 2011 that allowed Caravaggio’s arrival in Rome to be dated to Lent 1596 |

“What is certain,” Vodret continues, “is that Caravaggio was a person who did not go unnoticed, especially in court documents, through which it is possible to accurately document his appearances. So this long absence of documents has created quite a few questions: it is true that the archives in Venice have yet to be screened in this sense, just as a sweeping work has yet to be done on the Lombard archives (despite the wonderful amount of work Giacomo Berra has done), but it is curious that there is a four-year gap, and four years is a very long time.”

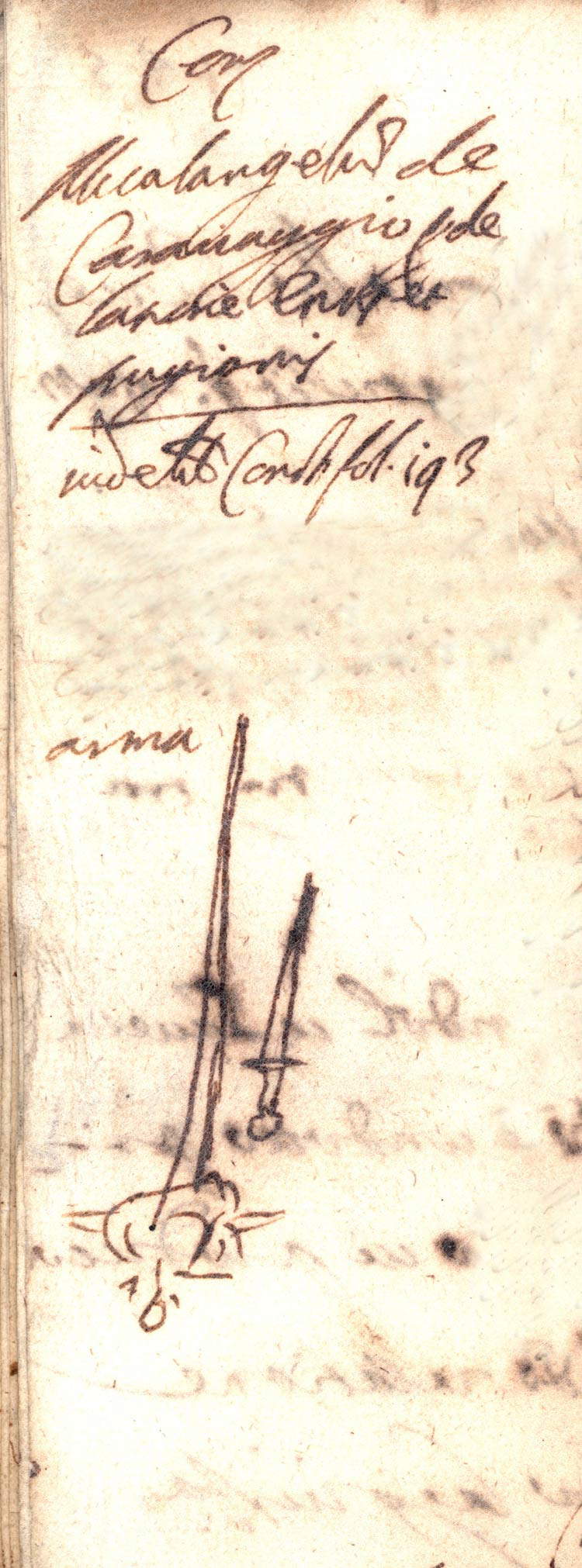

So could the idea of Caravaggio leaving as a soldier to go fight in Hungary be valid to explain the long period of silence? “Indeed,” Vodret explains, "this could be a solution, but it obviously needs to be studied. We just mentioned it in the book Places and Mysteries of Caravaggio because there are so many clues, but there is no document that proves it for sure. One clue could be the fact that Caravaggio had, undoubtedly, a mania for weapons: there are countless attacks on him, and in the inventory of his house of 1605 some weapons are recorded.“ Indeed, one finds, in the inventory in question, ”dui spade et dui pugnali de marra,“ and another dagger found inside a ”small chest.“ ”Incidentally,“ Vodret continues, ”two of these weapons, namely a sword and a dagger, were drawn when Caravaggio was arrested in 1605, and the sheet was also published on the cover of the catalog of the exhibition Caravaggio in Rome. A Life from Life, held at the State Archives in Rome in 2011, a seminal text. It is a sketch showing the dagger and sword with which Caravaggio had been caught, according to law enforcement officials without permission, which is why he was arrested."

|

| The drawing of the dagger and sword in the record of the April 28, 1605 arrest for illegal carrying of weapons, signed by Captain Pino |

“Talking about it with Mario Scalini, an expert on weapons,” Vodret explains, “I asked him why Caravaggio had to go around with a dagger and a sword, truly excessive equipment for an artist who apparently had no need to go around armed. According to Scalini, this was a typical set-up for the military, who at the time used to go into battle carrying a sword on one side and a dagger on the other. It seemed to me a very strange thing: so I wanted to investigate Spezzaferro’s idea (I would like to emphasize that we are still at the first verifications), that of Caravaggio leaving for the war in Hungary, which was fought precisely in these years, since it began in 1593 and ended in 1606. It turned out that several people who frequented the same circles as Caravaggio had fought in Hungary, although I am not sure why, for example, Giovanni Baglione’s brother Jacopo (who had also died there), Tommaso ’Mao’ Salini, and the soldier Petronio Troppa, who was with Caravaggio on the day of Ranuccio Tomassoni’s murder.”

As is well known, on May 28, 1606, he killed one of his bitter rivals, the Terni-born Ranuccio Tomassoni: for the murder Caravaggio was sentenced to death in absentia, and the conviction was the cause of the escape that took him far from Rome (to Naples, Sicily, Malta) for the last four years of his life, before his death in Porto Ercole in 1610, while the artist was waiting to return to the then capital of the Papal States. Rossella Vodret explains, “from the documents (I relied only on the documents: on Caravaggio you have to do that) we know that the episode from which the Tomassoni murder arose was actually a four-on-four clash, so a kind of showdown. And among the four who were with Caravaggio was also Petronius Troppa, a soldier who had taken part in the Hungarian War, and with regard to the Tomassoni murder it is necessary to record the fact that witnesses in the various stages of the trial mention other people who had been in the Hungarian War. It is as if an environment was created of people who had fought in Hungary. And in any case it is certain that at the time he was to go to the showdown with Tomassoni, Caravaggio brought with him a soldier from the Hungarian War, presumably a friend of his.”

“One last thing that needs in my opinion to be reasoned about,” Vodret concludes, “are also the ways in which Caravaggio kills Tomassoni, which are quite disturbing: following the narrative of the various witnesses, Caravaggio collides with Tomassoni, wounds him, Tomassoni runs away, Caravaggio chases him, Tomassoni falls to the ground, and while his rival is on the ground, Caravaggio hits him on the ’fish of the thigh,’ as Baglione says, that is, he severed his femoral artery. So this account that the witnesses give is very strong, because it is not a description of a duel, but almost of a military action. However, it still needs to be investigated at length in order to put together a picture.”

|

| Did Caravaggio fight as a soldier in Hungary before going to Rome? Here's what we know |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.