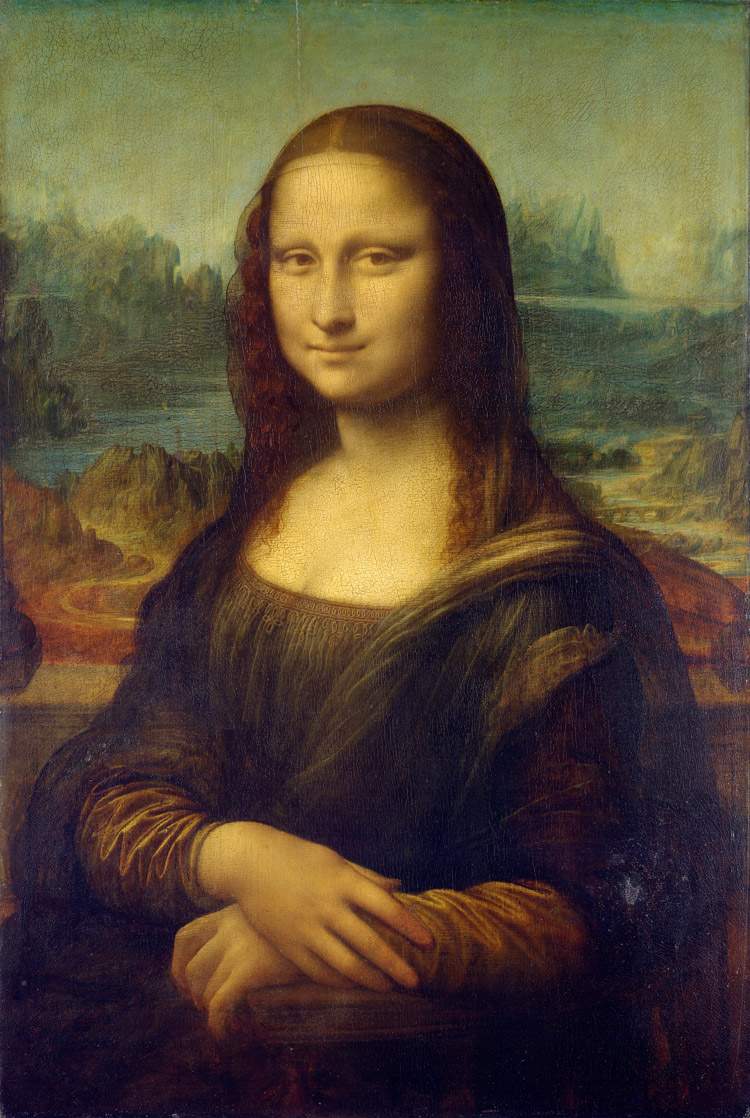

Because it is completely useless to try to identify the landscape of the Mona Lisa

Mona Lisa landscape seekers are back on the attack. There is no painting in the world that, over the years, has changed locations more, as they say. Thus come on an almost annual basis those who believe they have identified, more or less definitively, the landscape on which stands the most famous woman portrayed by Leonardo da Vinci. The latest in order of time is still Silvano Vinceti, president of the “National Committee for the Enhancement of Historical Cultural and Environmental Heritage” (the high-sounding and seemingly institutional name actually conceals a private entity founded by Vinceti himself), best known as a researcher of the remains of the greats of the past: over the years he has distinguished himself for having unearthed the remains of Boiardo, Petrarch, Pico della Mirandola, and even those of Mona Lisa Gherardini, as well as for having “identified” the artist’s bones in 2010, on the occasion of the 400th anniversary of Caravaggio’s death. It was rumored at the time that the DNA of those bones was 85 percent compatible with that of some people from the Bergamo area who go by the last name “Merisi” (meaning they could have been anyone’s, but that was not enough to deter the Porto Ercole administrations of the time from initiating major celebrations).

Vinceti is then known to have “discovered” numbers that Leonardo, for some reason, would have painted in the landscape of the Mona Lisa. And, of course, he could not escape the issue of identifying the landscape of the Mona Lisa. So here it is that in the painting Leonardo, news in recent hours, would have depicted the Romito Bridge in Laterina, in the province of Arezzo. In support of this thesis, there would be, according to Vinceti, some evidence such as the fact that “in the period between 1501 and 1503” the bridge “was in operation and very busy, as attested by a document on the state of the artifacts in the properties of the Medici family, found in the state archives of Florence,” and the fact that Leonardo at the time “was in Valdarno.” For what reason, among the thousands of bridges that we also imagine in operation and frequented at the time, the vincian would have had to paint that one, is unknown. Again, the fact that by passing over that bridge the artist shortened the journey between Arezzo and Florence: “and saving time,” asserts serious Vinceti, “allowed Leonardo to have more time to study.” But other elements would identify the bridge: for example, the “’anomalous’ wave” traceable “to a jump near a mill of the time.” Besides, Vinceti says, “The mistake that is often made is to think that Leonardo painted fantastic visions. On the Mona Lisa, yes, but not in the landscape”: because, in traveling to make his engineering works Leonardo “made very realistic drawings of places and details, which he then re-presented together.”

One has lost count of all the bridges that have been associated with the Mona Lisa: the Buriano Bridge in Tuscany, the Gropparello Bridge in the Apennines of Emilia, the Gobbo Bridge in Bobbio also in Emilia, the Azzone Visconti Bridge in Lecco, or unidentified bridges in Montefeltro, around Lake Iseo and in who knows how many other areas.And curiously enough, some of Vinceti’s admirable discoveries have given the cue to his rivals: for example, the number “72” that the committee chairman is sure to see under the Mona Lisa bridge, according to another mystery solver would identify the Bobbio bridge, due to the fact that in 1472 the river it crosses had a flood. More arduous is to explain for what reasons Leonardo had to employ such a brainy way of allowing a bridge to be identified: in fact, no one has bothered to give explanations for this.

The question about the identification of landscapes in Leonardo da Vinci’s paintings is actually closed and there is no point in reopening it. The short explanation: Leonardo did not paint real landscapes, he did not use a brush as we would do with a camera today. To begin the long explanation, it would also suffice to use one of Vinceti’s own arguments, when he says that Leonardo “made very realistic drawings of places and details, which he then re-proposed together.” Therein lies the point: if Leonardo had been extremely precise in his paintings today we would have no difficulty in recognizing the settings of the Mona Lisa. Instead, so many have been proposed, almost always by non-Leonardo specialists from certain geographical areas who have claimed to recognize them in the Mona Lisa. It is worth retracing some of these attempts: Sandro Albini, a health professional from Brescia, has considered identifying the Oglio plain between Bergamo and Brescia in the landscape of the Mona Lisa. Historian Carlo Starnazzi, who studied Leonardo’s maps at length, felt that he identified the Buriano bridge in the bridge (which, moreover, has seven arches, while the one in the Mona Lisa has fewer, or at any rate we are unable to determine how many arches are concealed behind the Mona Lisa’s back). To complete the picture, one could cite the attempt of an Urbino photographer who, in order to claim that the landscape behind the Mona Lisa is that of the lands of Feltre, went so far as to deny the identification of the woman with Lisa del Giocondo, asserting that the lady is actually an Urbino gentlewoman, Pacifica Brandano. Finally, it has also been proposed that the Roman countryside is identified in the landscape.

One can close the matter definitively by quoting the words with which an acknowledged expert on Leonardo da Vinci, Martin Kemp, in his book 50 Years with Leonardo, directly addresses the "lovers of landscape secrecy,“ as he calls them. ”There is no reason to think that Leonardo intended to depict specific places in his paintings,“ Kemp explains. ”In all aspects of his art (and science) his concern was to ’re-create’ nature based on his understanding of the mechanisms that govern it. The view behind Lisa, designed to provide a meaningful echo of the microcosm (lower world) of her body, is strongly influenced by Leonardo’s knowledge of geology. The two lakes formed at different levels, mountain slopes, and meandering river beds are all depicted based on his hard-earned knowledge of geological processes, not copied from particular views. Art for Leonardo was as much a demonstration as his scientific illustrations and diagrams. It is this act of forging an archetypal mountainous landscape that allows the background to be relatable to different views without, however, being identical to any of them. So the craggy rock strata and jagged peaks of the Corna Trentapassi are exactly the kind of formations that fascinated Leonardo, but he did not intend to make a precise transcription of this or any other specific place."

It is therefore perfectly useless to look for real landscapes inside the Mona Lisa, for the reasons given above. The next time a statement arrives in your newsroom announcing an astonishing discovery along these lines, you can respond with the far more serious arguments of those who have devoted a lifetime of study to Leonardo da Vinci. And you will then be able to ignore the stimulus of those who claim to have definitively figured out in which part of Italy Leonardo sat the Mona Lisa.

|

| Because it is completely useless to try to identify the landscape of the Mona Lisa |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.