Art to revive crafts in Val Camonica: Stefano Boccalini's experience

A hub for art and crafts among the mountains of the Camonica Valley: it is Ca’ Mon - Community Center for Mountain Art and Crafts, which opened this summer (it opened on July 17) in Monno, in the Upper Camonica Valley, the idea for which matured as part of the project La ragione nelle mani (Reason in the hands ) by artist Stephen Boccalini (Milan, 1963), winner of the eighth edition of the Italian Council call, a program to supportItalian contemporary art in the world promoted by the General Directorate for Contemporary Creativity of the then MiBACT, Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism.

Stephen Boccalini and the Distretto Culturale della Valle Camonica have been collaborating for several years, and the exhibition La ragione nelle mani (in Geneva, Musée d’Art et d’Histoire, from April 1 to June 27, 2021, curated by Adelina von Fürstenberg, Archive Books catalog) is the first in a series of initiatives under the project of the same name, carried out in collaboration with important cultural partners (and which Boccalini is now taking on tour throughout Europe); the Musée Maison Tavel-Musée d’Art et d’Histoire (Geneva) home of the exhibition, the Art House in Shkodra, Albania, the Sandefjord Kunstforening in Sandefjord (Norway), the Fondazione Pistoletto Onlus in Biella, the Accademia Belle Arti Bologna, MA*GA - Museo Arte Gallarate and GAMeC Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea Bergamo. After bringing the signs of Valle Camonica to Europe, the work designed by Boccalini, composed of various artifacts, will become part of GAMeC’s collection. The idea for the project stems from the relationship that Boccalini has built with Valle Camonica since 2013: from a residency on the theme of water, the artist got to know better this beautiful place in the Lombard Alps that in the past he frequented only as a tourist. Over the years, Valle Camonica has become a reference point for his work: here he has worked with various communities, local institutions and artisans, creating a close working relationship that has allowed him to produce numerous works.

Ca’ Mon: a center for mountain art and crafts.

This experience and these encounters led to the idea of creating a Community Center for Mountain Art and Crafts. Ca’Mon is a center of exchange between intellectual and manual knowledge, created to activate a confrontation with the territory artists, authors and researchers will be hosted in residence. Ca’Mon is also a place of training, equipped with laboratory spaces where artisans, artists and young people from the valley will work.

Through restoration and re-functionalization work, the space has become a home for knowledge rooted in the Monnese tradition (including those related to the typical Monnese “pezzotti”), but it also intends to be a center of experience in which to pass on that same knowledge to new generations and share the common memory of an entire community. Artists, designers and more generally authors and researchers will be hosted in residence at Ca’ Mon to activate a confrontation with the territory. What’s more, it will also be a gathering place open to the entire community of Monno, and beyond, where experiences can be shared and relationships cemented through “making.” Ca’Mon is a project desired by the municipality of Monno together with the Comunità Montana di Valle Camonica and the social cooperative “Il Cardo” of Edolo, made possible thanks to funding from the CARIPLO Foundation as part of the “Beni Aperti” call for proposals.

“The artisanal work of Valle Camonica,” explain Sergio Cotti Piccinelli and Giorgio Azzoni, director of the Distretto Culturale di Valle Camonica and director of the public art event aperto_art on the border, respectively, "was translated not only into artistic conception and experimentation but also into a space for sharing and professional exchange. The collaboration in artistic production has been operational and daily to such an extent that it has led to the conception of a Community Center for Mountain Art and Crafts located in Monno - a small village of about five hundred inhabitants located in the upper valley, where to incubate and grow a new way of making art and crafts together and where it was possible to connect the territorial sense with the international dimension, involving young people in educational paths in which to interact as much with tradition as with contemporaneity, so as to foster new directions of growth of the territory and new sustainable economies, respectful of biodiversity. It is in relation to the birth of this new Center, of which Stephen Boccalini has been identified as artistic director, that the bond between the artist and the territory of Valle Camonica has intensified, up to the sharing of the project La ragione nelle mani."

“The project,” Adelina von Fürstenberg points out, "was born on the basis of a constructive conviction that identifies the artisanal tradition of the Camonica Valley as the point of origin for a truthful aesthetic experience. It is the kind of experience that Bauhaus artists were already seeking when back in 1919 Walter Gropius, wanting to bring art into dialogue with craft aesthetics, had emphasized in the Bauhaus’s inaugural manifesto: ’Architects, sculptors, painters, we must return to craftsmanship!’ ’Rational functionalism is technique. Irrational functionalism is art,’ wrote Josef Albers (1937) to emphasize exactly this intersection of knowledge. So for Boccalini, art manifests itself through awareness, concepts and emotions, while the artisans of the Camonica Valley, with their centuries-old technique and savoir faire, embroider, carve, weave and weave the artist’s untranslatable words, thus revealing the reason that lives in their hands."

“Stephen Boccalini, pragmatically, seeks the revival of craft techniques,” says Ivan Bargna, full professor of Aesthetic Anthropology and Media Anthropology at the University of Milano-Bicocca, “so that they can become crafts again. So in the project he promotes, each master is flanked by apprentices: artisans transmit their know-how to young people, while the artist prefigures and suggests new creative possibilities that allow them to hold up to the challenges of contemporaneity without having to surrender to market logics. His is a very narrow path: if this endeavor can have any chance of success, give some form of livelihood to individuals, and at the same time contribute to changing the planet, it is because it rests on the in-actuality of artisan work by making it the possible model of an ecologically sustainable relationship with the world.”

“Ca’ Mon,” Boccalini emphasized, “will also become a place where communities can recognize themselves and where it will be possible to bring to light all the issues related to the past, useful for the construction of the future and momentarily sidelined, which here can find the conditions to regenerate and take on new forms: it opens the possibility for a permanent laboratory of experimentation and research that, starting from a local condition, wants to counter the culture of diversity and biodiversity to the homogenization to which the dominant contemporary society tends.” The goal, the artist concludes, “is the transmission of knowledge, according to a logic of sharing for which traditions do not take on a nostalgic sense but become the gateway to the future, a ’place’ of experimentation to imagine new scenarios.”

Reason in the hands

The project The Reason in the Hands moves on two levels, that of language and that of craft knowledge, through the involvement of the local community. It is a large work composed of seven artifacts that were made in Valle Camonica by four artisans each joined by two young apprentices. The eight “apprentices” were selected through a public call for entries, promoted by the Mountain Community and aimed at young people in the valley interested in engaging with craft practices belonging to the Camonica tradition: pezzotti weaving, wood weaving, embroidery and wood carving. These craft forms, which historically held a function of primary importance in the social and cultural fabric of the Valley, today struggle to withstand the changes imposed by modernity, and few still know the ancient techniques. “We live in an age,” says Boccalini, “in which words have become a real tool for production and capturing economic value, and have assumed an increasingly important dimension within the social context. Through their use, I try to restore a specific weight and collective value to language, which for me is the ìplaceî where diversity takes on a fundamental role, becoming the means by which to contrast economic value with the value ’of the common.’”

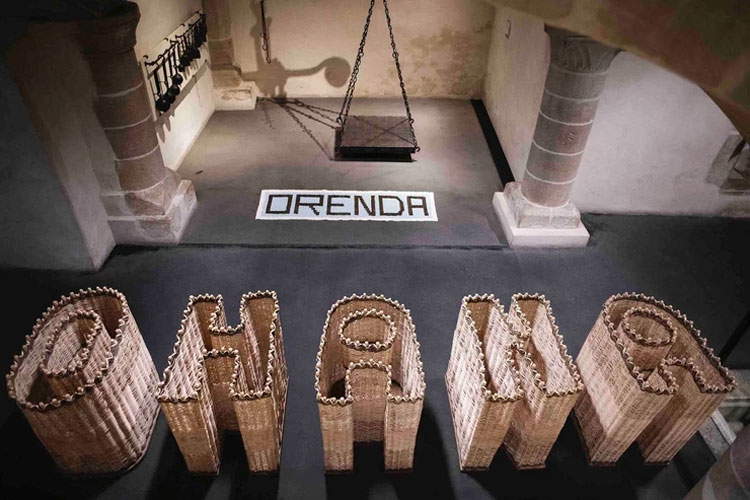

Reason in the hands kicked off with a workshop involving all the children of Monno, who were told about the meaning of about one hundred untranslatable words (as they have no counterparts and therefore can only be explained) that are found in many languages. Together with the children, about twenty words identifying the relationship between man and nature and between human beings were chosen. The words were finally submitted to the artisans to see which ones might be the most suitable to be transformed by their hands into artistic artifacts. Nine were chosen that became the material on which the artisans worked with the apprentices. The words, which will be explained here with short expressions, are Anshim (“Feeling in harmony with oneself oneself and with the world,” Korean), Balikwas (“Abounding in one’s comfort zone,” Filipino), Dadirri (“Quiet contemplation and deep listening to nature,” Australian Aboriginal languages), Friluftsliv (“Connecting with the environment and returning to the biological bond between man and nature,” Norwegian), Gurfa (“thewater that you can hold in the palm of your hand as a metaphor for something very precious,” Arabic), Ohana (“family that includes friends and leaves no one behind,” Hawaiian), Orenda (“the ability human to change the world against adverse fate,” Native North American languages), Sisu (“the determination to seek well-being in everyday life,” Finnish), Ubuntu (“I am who I am by virtue of who we all are,” Southern African languages). “If language is a common good,” comments economist Christian Marazzi, “then it is up to the community to take care of it. At stake is the health of the community of speakers, its communicative and relational actions, its very faculty of language. Taking care of language means returning things to words, remaking words with things, giving them community texture. It is not a matter of materiality but of sociality, of reconstructing the web that weaves community through the multiple forms of making, which have given substance to language as a common good.”

The work consists of a white-on-white “carving stitch” embroidery with three words, mounted as a painting; two carved walnut woods that feature two words; five woven hazel wood artifacts, made with the technique used to create baskets and panniers, that together make up one word; and three pezzotti, rugs made from handloom-worked textiles, each of which reproduces one word. “The execution of Boccalini’s work is no small matter,” Adelina von Fürstenberg explains. “The works are not fabricated simply by following instructions given a priori, but are executed by the artist himself together with the artisans, involved in an exchange of knowledge between the poetics of the work and the craft tradition, incorporating their knowledge into artistic and pedagogical practice. In this, Boccalini fits fully into the tradition of Arte Povera, an art that does not interpret but simply perceives the flow of life and the environment, using materials hitherto never considered, and placing its attention not so much on the work of art as on the process of creation itself. In Boccalini’s work, however, through research and choice of untranslatable words, he creates a biodiversity of concepts from linguistic minorities. The works derive solely from the importance of the meaning of the word employed, and the material and craft means with which they are executed play a crucial role.”

“The result of all this work,” Boccalini concludes, “is not only represented by the works, but also by the process that led to their construction. A process that has put back into circulation the knowledge and practices related to the tradition of the valley but with new perspectives and awareness.”

|

| Art to revive crafts in Val Camonica: Stefano Boccalini's experience |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.