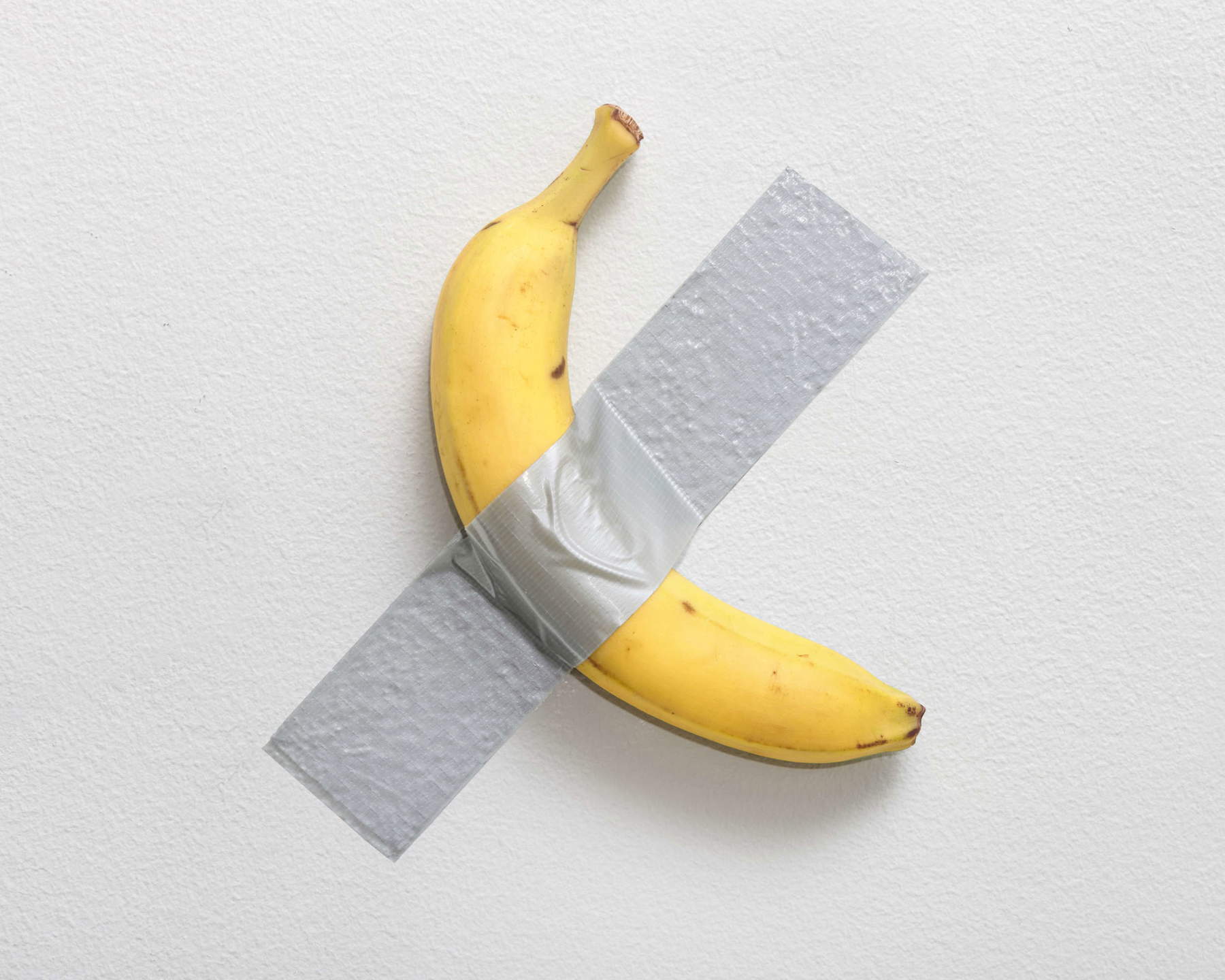

Fortissimo is the uproar aroused these days by Comedian, the work by Maurizio Cattelan initially presented in 2019 at Art Basel Miami at the booth of Perrotin, Cattelan’s gallerist: the work was in fact sold at auction by Sotheby ’s in New York for the sum of $6.24 million. A very high figure indeed, taking into account not only that the work was estimated at $1-2 million, but that in 2019 it sold for just $120,000! In short, today we all regret not having pawned our two-room apartment five years ago to buy the work and become millionaires today, but after all, that figure seemed high to us even at the time: we could not conceive that a banana attached with simple tape to a wall could cost as much as an apartment. And so many were outraged, many criticized the artist, many discussed wondering if really Comedian can be considered a work of art. We then decided to give an articulate answer to many questions that have emerged from the debate, some explicitly, others perhaps more implicitly (for example, many accuse Cattelan of mocking the public, of being a fraud: but is this really the case?). We then provide below 10 questions and answers, 10 FAQs to use typical Internet jargon, to understand Cattelan’sComedian . For those who want to go deeper, we also suggest reading Federico Giannini’s critical piece (from 2019, shortly after the presentation of Comedian), Comedian: a work in which everything is Maurizio Cattelan.

Comedian is a work of art because it is a creation produced by an artist. However, in this case, Comedian shifts the focus from the traditional art object to the concept it represents, challenging our understanding of what art is. It is not just a banana stuck to the wall, but a gesture that questions the symbolic, cultural, and economic value of objects and is critical of the very system that produced it. It is a ready-made, that is, an ordinary, everyday, even banal object that is, however, moved into an artistic context (for example, an art gallery) and thus becomes a work of art by the decision of an artist who is universally recognized for being, precisely, an artist. The ready-made, also known as objet trouvé, is the material with which the work is created and, by extension, becomes the expression with which we

Comedian fits neatly into the strand of relational art, an art form born and developed in the 1990s that sees the work of art as a tool for confrontation, discussion, debate, and relationship. Relational artists like Maurizio Cattelan are wont to shift the audience’s attention to the context, rather than the object itself. And Comedian works exactly like this: he creates a space for discussion, controversy, and reflection that invests, in his case, not only the relatively narrow art system, but the entire public sphere. Some might also interpret Comedian , more simply, as a work that can be included in conceptual art, a current that places the idea at the center of artistic practice, often at the expense of aesthetic value or technical achievement. In conceptual art, what matters is not the physical object, but the message or thought it conveys. In this sense, Cattelan stands as heir to artists such as Marcel Duchamp, who with his Fountain (a signed urinal presented as a work of art) changed forever the way art was conceived and judged. In a sense, Comedian speaks more about the context than the object itself: its meaning emerges from the interaction between the artist, the audience, the market, and the media.

No, not at all. Comedian does not and cannot even have a single definite meaning, because if it did, its charge would be greatly dampened: if Comedian were reduced to a single meaning, it would lose much of its power. Even the title itself is ambiguous, difficult to decipher, no matter how much one may argue around it. The ambiguity and polyvalence of its message are fundamental features not only of contemporary art, but also of Maurizio Cattelan’s artistic practice. The work does not impose an unambiguous reading; on the contrary, it stimulates a multiplicity of interpretations, each of which depends on the cultural, social and personal context of the viewer. It can be a critique of consumerism, an analysis of the art market, a contemporary vanitas , a reflection on the status of art in our society, it can be so many things. A work like Comedian does not claim to say something definitive. Rather, it acts as a catalyst for thought and discussion. Cattelan does not provide a clear explanation or a manual for interpreting the work, leaving room for the audience to fill this void with their own ideas, emotions, and perspectives. It is an open dialogue, not a lecture given by the artist-that is the beauty of relational art. The artwork, more than an object, is an intellectual experience.

No, it is the exact opposite: it costs so much because it is a work of art to which a high economic value is attributed. The high price of Comedian does not define its artistic nature, but rather is an effect of the contemporary art system. The work would be art even if it cost nothing, because its value lies in the concept it represents. Cost is, as mentioned, a reflection of the value that the market places on the work. We can then try to imagine, speculating, that initially the price set by the Perrotin gallery, the first to sell Cattelan’s work ($120,000) was part of the message, in the sense that Cattelan perhaps wanted to show us how society attaches meaning and importance to objects based on external factors, such as money, prestige, or the artist’s name. But in reality the estimate and auction result, over $6 million, are independent of the artist’s will.

The value of Comedian lies not in the material (a banana and some tape) but in the idea and the context in which it was presented. The person who bought the work did not buy a physical object, but a work of art represented by a concept, and bought the right to replicate it. The buyer recognized in Cattelan an artist capable of capturing the spirit of our time, and the price paid reflects this recognition. Another factor is the prestige associated with owning a famous conceptual artwork. Buying Comedian means not only owning a unique piece of contemporary art history, but also participating in a cultural discourse that goes beyond the object itself. It is like buying a symbol: those who own Comedian own a piece of the global conversation about art.

The buyer bought the authenticity and authorship of the work. Although anyone can take a banana and tape it to the wall, only the buyer who has the certificate of authenticity issued by Cattelan can claim that that installation is Comedian. This distinguishes the original work from any copy. It is the same principle that applies to Duchamp’s ready-mades or minimalist works that can be replicated. The artist’s idea is what is bought, along with the right to declare that particular manifestation is part of his or her creative vision. This shifts the focus from material product to concept, an idea that is now central to contemporary art.

No, far from it! Comedian is a completely transparent work, it does not pretend to be something it is not, and to say that Comedian is a scam is to miss the intellectual game proposed by Cattelan. There is no deception in the work: the audience and the buyers know exactly what they are buying. The whole operation is done in the open, and its value lies precisely in its ability to reveal the paradoxes of the art market. For the public, therefore, it is an operation that is not only honest, but of great cultural value since it prompts each of us to question the status of the work of art, the meaning that the market attaches to it, and above all the role that art can play in the lives of all of us.

No. Of course, we can say that Comedian is also an ironic work, but to call it a “tease” would be to greatly underestimate the complexity of its many meanings. Cattelan does not mock the public or art for the sake of it: if anything, he uses the medium of irony, as he has always done, to highlight the dynamics of the contemporary art system. As for the idea that Comedian is a provocation, it cannot be considered a provocation for its own sake, because its purpose is not to scandalize the well-meaning; that would be very reductive. At most we can consider Comedian a provocative work of art, but even then it would mean limiting the scope of its meaning. In fact, Maurizio Cattelan’s Banana does not merely scandalize, it invites reflection on important issues such as the commodification of art, consumerism, the precariousness of life, and the role of the artist in contemporary society. In short, Cattelan uses irony and provocation to expose the contradictions of the world in which we live.

Free to do so, but it would be like refusing to consider the Ramones musicians because performing their music, and punk in general, requires far less technical expertise than that required to perform Paganini’s 24 caprices. The fact is that to judge Comedian by its material execution is to fail to understand the nature of conceptual art, which shifts emphasis from technique to meaning. Sure, banana and duct tape do not require extraordinary manual skills to assemble, anyone can do it at home, but since Marcel Duchamp we have learned that work is not measured in terms of technique or beauty, but rather in terms of the ideas and dialogue it is capable of generating. Comedian falls within this tradition: the artist does not want to impress with technique, but to provoke an intellectual and emotional reaction. After all, when we see a contemporary marble sculpture that impresses us, in most cases we are looking at a work executed almost entirely by a machine: the artist today intervenes only in the final stages of execution. And then, anyway, Comedian has strict aesthetic standards, recognized even by the judge in the trial in which Cattelan was accused of plagiarism by an American artist (and, by the way, Cattelan won).

No, we cannot consider ourselves defeated, but we must accept that art, like any form of human expression, evolves with the times. Michelangelo’s David reflected the values of the Renaissance, while Comedian, on the other hand, reflects our time: an age marked by consumerism, showmanship, precarity, and changing social relations. Art has always reflected the cultural, social and economic changes of its time. Think of Impressionism, which was initially criticized for its rejection of traditional academic painting, or Cubism, which destroyed the rules of Renaissance perspective. Every era has had its artistic revolution, and many of them were met with skepticism before being recognized as fundamental: those who reject Cattelan’s Comedian today are behaving exactly like the public who, in the nineteenth century, rejected the Impressionists or, in the early twentieth century, rejected Picasso. To consider ourselves “defeated” because art has changed would be to fail to recognize its ability to adapt and respond to the needs of each era. The real defeat would be not to accept this evolution; it would be to remain fixed to an outdated, backward-looking idea of art, unable to take into account the challenges and contradictions of the present.

|

| 10 questions and answers to understand Cattelan's Comedian: why a banana is a work of art |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.