The great reflection: The Italian Renaissance Altarpiece, David Ekserdjian's magnum opus

In 2021, the Art Newspaper chose as its book of the year David Ekserdjian’s monumental work The Italian Renaissance Altarpiece: an endeavor that we could call “the great reflection” on the greatest pictorial phenomenon of the Italian Renaissance, namely on the innumerable scattering of altarpieces in Catholic churches, in which all the geniuses of the time and minor masters from every region participated (it can be said): a massive act and axial event in art history. This act has so far lacked an investigative and explanatory work that would illuminate its overall reason and the network of links, taking into account that the universe of altar paintings sums up in itself biblical, early Christian, historical-religious and customary values, in the most varied figurative overlaps, subject to compositional interpretations that are the responsibility of very different artists and subject, at least in certain ways, to the conditions of equally sought-after commissions. A non-comparable study, then, which the author conducted with true unity of purpose, being endowed with a very wide-ranging culture.

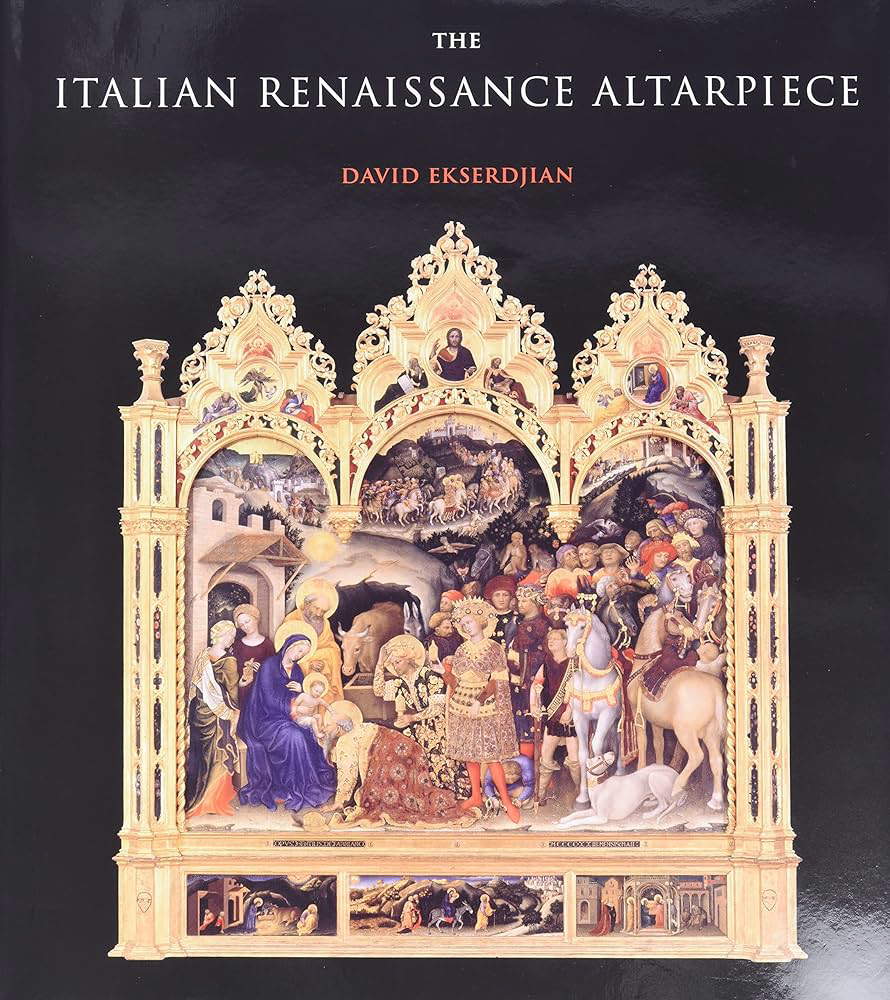

Let us first look at the objective data of the publishing work. A large-format volume (cm. 28.5 x 24), packed with 496 pages and more than 250 color illustrations; a well-articulated textual endowment with an extensive introduction, followed by the seven thematic chapters, enriched by a conclusion and two appendices. There are 2574 notes at the end of the volume, clearly distributed. To this astounding furnishings are added a very extensive bibliography, indexes and credits. It was not for nothing that the author told me this was the greatest exegetical monument he had ever raised, and he declared its unrepeatability during a lifetime. My present notes are intended to keep alive the desire for a broad national knowledge of David Ekserdjian’s work, which we would like translated into a desirable Italian edition.

We wish to emphasize here the importance of altarpieces as a totalizing fact of that architecture encompassing spaces and furnishings that accompanied the Catholic liturgy in the second Christian millennium. The late medieval instance of perceiving beyond the altar a solemn, mystical, and evocative vision, at first reserved for the walls of the apse and the bowl, tightened closer and closer to the table when the celebrant of the holy mass began to turn his back on the people to become the leader of a praying throng looking to the cross. The first movable apparatuses “behind the altar” are the wooden altarpieces, which become larger and larger, and their central figurations will initiate the story of the actual altarpieces with their specific history: from wooden panels to canvases, sumptuous frames, and even theatrical altarpieces that will come to be elaborate. This phenomenon soon led the Catholic churches to the loss of that indispensable element for the early Christian and Romanesque faith that was the central window of the apse, the “Gate of the Sun,” when in the morning empyre entered the Light from the East, that is, the very presence of Christ.

Noting the replacement role of the altarpieces, let us return to the editorial enterprise of David Ekserdjian, who begins the introduction with a maxim from La Rochefoucauld about the knowledge of a work of art, “which will always be imperfect until the sharpest unraveling of every detail”: a statement of work, to be sure, but perhaps also a benevolent self-admonishment typical of the character of this British author, always close to facetious humor. The introduction itself is an act of homage to the few authors, Italian and foreign, who have dealt with the subject but with partial or enumerative views; very important, however, is the treatment of typologies, the development of forms, the compositional weight of the altarpieces, the shrine presences, the narrative aspects, the value of inscriptions and ornaments; finally, the relationship with the Mass and the choice of sacred characters (a very rich and careful part). With this initial scaffolding, dense with over 50 pages, the entire construct of the volume is set. A first example of the different figurative-imaginative latitudes of the Pale the author offers us in the comparison, in the Emilian field, between two coeval altarpieces by Luca Longhi and Correggio where the former inserts an untenable spatial event, and the latter a mystical co-presence outside the temporal logic, but admirably harmonious. The whole treatment of this part is of high interest, deep culture and dense documentation.

Two examples, in obvious distance, of compositional conception. Longhi labors, as it were, to enter the identification of the two saints by having St. George’s horse burst in front of the stage of the Madonna and Child, where on the floor the little dragon stirs. In a lower dimension kneels the noble patron, clearly in connection with his own heraldic coat of arms. Correggio, for his part, gathers the very different characters, who participate in the divine approval of the translation of the Bible, in a harmonious co-presence that is entirely naturalistic

The seven broad chapters that follow carry out the task proposed by the Introduction. The first is entitled “Principals, Artists and Contracts.” Here the Author’s almost universal background in the Italian field is squared off in a dense network of examples of the most curious interest as the desires of patrons(patrons) ranged from the most traditional devotions to almost unimaginable particularisms, between faith, local interests, personal ambitions, and wide-ranging character calls. But the chapter particularly focuses on the modes of the drafting of contracts, which are also the most varied: from precise notarial acts to lengthy dictations by devotees, nobles, and confraternities, to the surprising, very short notes delivered into the hands of the great masters almost like pleading acts, but accompanied by unfailing advance fees. Thus in some contracts one can already read, almost in full, the paintings in all their arrangement, the number and subjects of the figures, and other insistent minutiae, including the colors. The delivery date was obvious and recalculated (but was often the cause of disagreements between patrons and painters). The analyses here conducted by Professor Ekserdjian also include the painters’ opportunities to include their own self-portraits in the composition, but often the requirement for portraits of the donor or interested persons, and include the importance of inscriptions, which were always expected. The auras were the subject of lively predispositions of the patrons, and could only be removed, in their works, by the authority of the major masters. The final part of the chapter is devoted, with great intelligence and with punctiliousness of research, to “what happened after the contract”: a very long part, new in scope, of true historical enlightenment.

The second chapter is entitled “The Virgin and Child and the Saints,” and here the examination of the content types of the altarpieces begins. In evidence, the great majority of these show the Virgin with the Child Jesus on her knees; the Madonna stands in a raised position, very often enthroned, and usually holds a few Saints around her. This center of attention resolves certain needs of faith and impetration: Jesus as God is present, Mary’s divine motherhood is assured as well as her role as mediatrix of all graces, which can be transmitted by the protectors. Other altarpieces depict the Crucifix, sometimes surmounted by the figures of the Father and the Holy Spirit. Turning to minor altarpieces, probably intended for side altars, we can find the saints without the deity, and in that case they convey examples or assure protections that we might call “specialized”: assistance in travels, relief in poverty, healings in various illnesses or at certain junctures in life. Angels are also invoked for the same reasons and also for spiritual and virtuous concessions. Here the author masters the innumerable number of panels and canvases that throughout Italy surmount altars, and his continuous weighing of the various presences is acute; the iconographic apparatus is of great merit.

Strange composition at the center of a polyptych commissioned in his time by the guardian father of the Franciscan convent of Alba. Here, while St. Francis receives the stigmata from an uncomfortable seraphim, Friar Leo, kneeling, holds the portrait of the guardian father Enrico Balistero who can thus participate in the miraculous event.

Masterpiece by the prodigious painter, the subject of countless events, from commission to composition to incompletion due to his early death

In place of one of the many Madonnas placed above, it is strong to look at this panel where Bramantino, with Lombard realism, brings to the ground the seat of Mary with Jesus and places them in direct dialogue with St. Ambrose (who holds the scourge next to him), to whom the Virgin holds out the sign of purity, and with St. Michael who presents a soul for judgment, to whom Jesus earnestly desires to forgive. In his “fantastical imagination” and through such scathing symbolism Bramantino casts the heretic Arius (St. Ambrose’s opponent) to the ground and also the devil himself, in the form of a huge frog with clawed legs as seen in medieval holy water fonts. Thus on the visual level Bramantino responds formidably to Mantegna’s foreshortenings but the meaning of the sacred conventus, very close to the faithful, opens wide a sum of doctrinal truths

Chapters three, four, five and six of David Ekserdjian’s impressive work are devoted to the narratives that are illustrated in the various types of the Italian Renaissance Pale. These chapters constitute the great heart of the work, and to give a summary of them is no easy matter. The reader is therefore more intensively directed to the entire original, foundational text. Chapter Three opens with a survey of the disputes and disagreements that involved painters, theologians, church masters and strong popular representations, such as the Confraternities, about whether people, saints or historians or even crowds, from different eras could be recalled alongside episodes from the life of Christ and other events, such as martyrdoms or visions. If we have to designate who won, we would not hesitate to say the Christian people, who were understood and supported by distinguished pastors, so that such endorsement has remained over the centuries.

Chapter Three is entitled “Narrative Altarpieces: The Virgin and Christ” and, after the introduction, is divided into successive topics: Histories and Icons: The Documentary Record - Single Events and Narrative Cycles - Old and New Testament Narratives - The Parents of the Virgin, her Early Life, and the Infancy of Christ - Between Christ’s Infancy and the Passion - The Passion of Christ - After the Resurrection - The Last Judgement and All Saints - a final note follows. The reader will understand the areal breadth of this exploration, always precisely attentive about the time and characters that accompanied the great moments of Redemption. We will limit ourselves to offering a few pictorial examples.

The large panel bears witness to the continuous presence of angelic spirits alongside human persons and events, just as Christians always believe. To them, not infrequently, the altarpieces of particular chapels are dedicated. Here St. Michael and the other two Archangels plunge the devil into the underworld

St. Nicholas, revered in southern Italy, is depicted enthroned but on earth, and has mystically come among his people to procure dowries for three poor maidens: according to ancient belief he is delivering to them three golden apples. Here the saint acts directly for a grace

In this large panel, the skilled Florentine painter, before working in the Sistine Chapel, demonstrates an effusive animosity in the composition: the infant Jesus is adored by Mary, the three Magi, and saints Benedict, Jerome and Francis, all of whom are expelled from the places and times. Above, in the atmospheric sky, the Father and the Holy Spirit appear among angels; a small distant figure perhaps recalls the presence of St. Joseph. The time of day is bright and the landscape serene. This is a devotional testimony that surpasses historical and physical data and will have pleased the patrons somewhat

At the end of the 16th century, pictorial libertates became total. The pious Barocci even goes outside the Gospel texts and creates a space, a manner, many presences and related gestures that do not correspond to Jesus’ Last Supper. Christ himself offers the host and not the broken bread. This unreal updating of the institution of the Eucharist was proposed and received pictorially as a didactic for the people; the beautiful canvas still remains on display in the famous Roman church

This modest and good painter from Sabina offers the faithful in his small towns frolicsome images of Christian reality. The wooden altarpiece has an arched Renaissance structure above a tall predella of archaic flavor showing three protagonists of Mary in her motherhood. In the middle of the altarpiece proper stands out the divine award to Our Lady with the coronation by the Father, while from below and around it winds a figurative climb with angels, Apostles, saints and other heavenly spirits, to popular jubilation

The theme of the “Judgment at the End of Time” had always been reserved for medieval frescoes and large surfaces, especially the counterfacades as a “memento” to the faithful as they exited, but since the Renaissance it disappeared from the Shovels of the major altars. This small wooden specimen faces the threshold of the 15th century and comes from the island of Majorca where the late Gothic Florentine painter had been called.

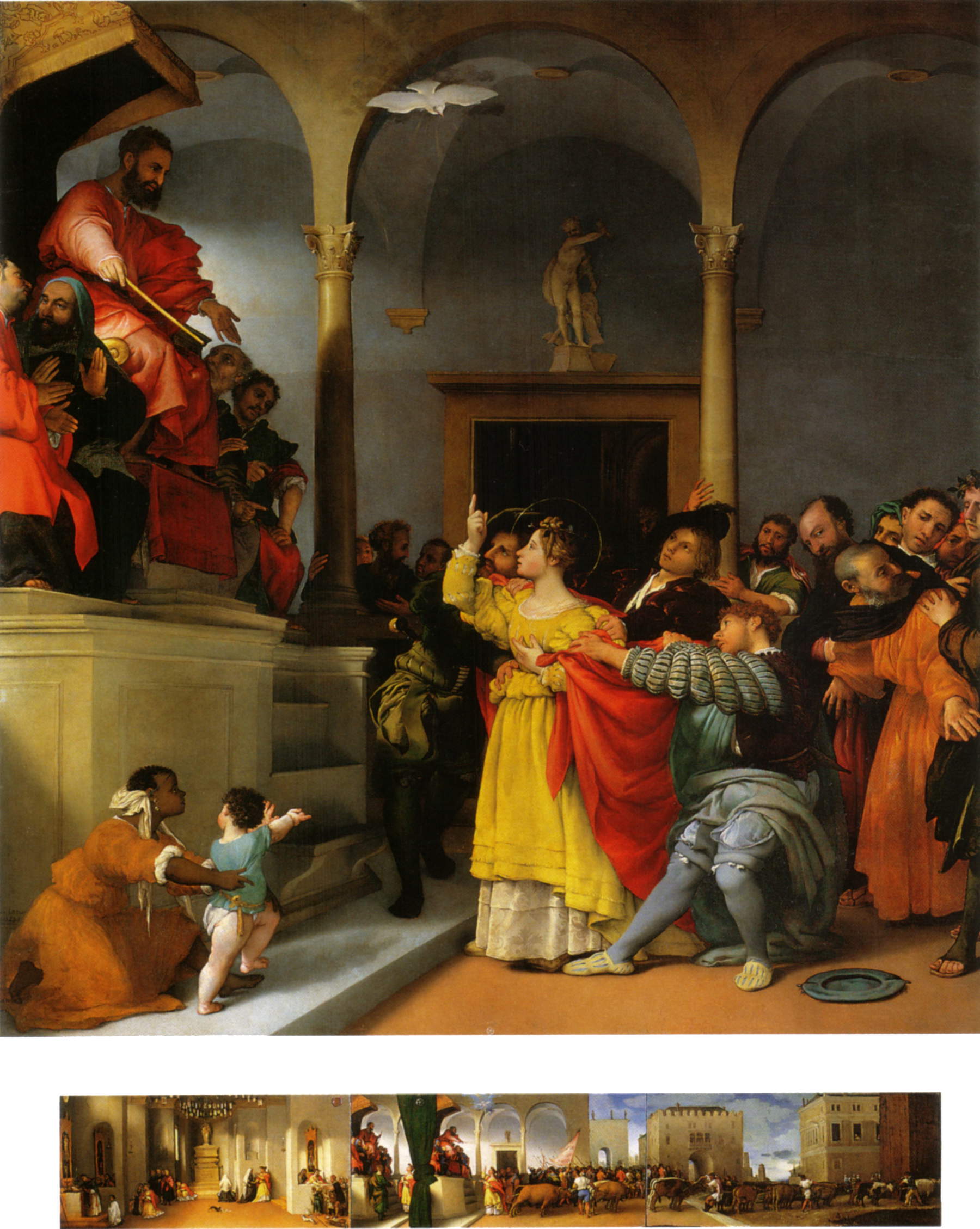

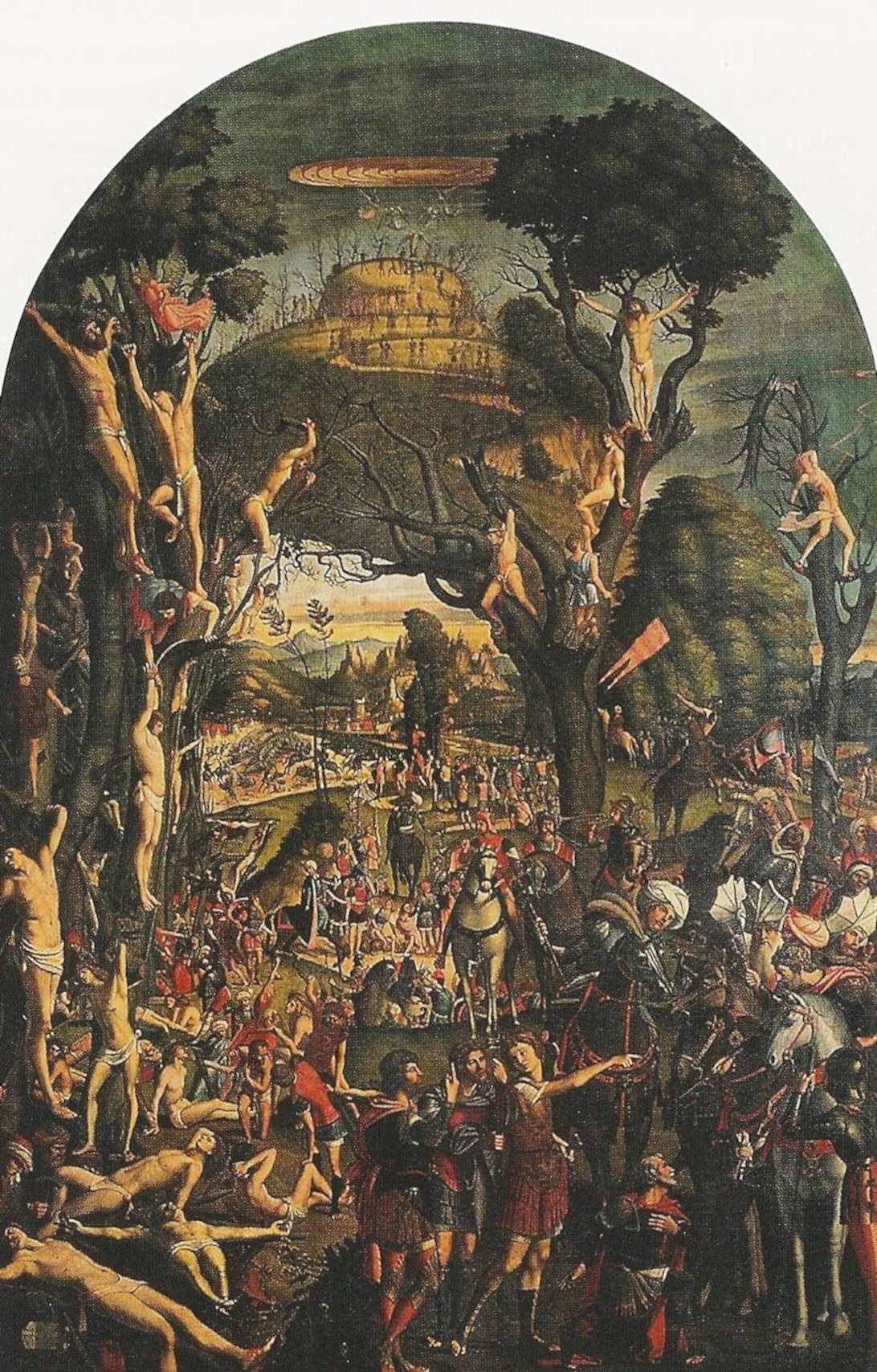

The fourth chapter is entitled “Narrative Altarpieces: The Saints,” and after the foreword, the articulation includes Saint John the Baptist - The Apostles - Mary Magdalen - The Martyrs, very broad - Monastic Saints - The Doctors of the Church - Popes and Bishops - The Angels - and the short Patron Saints - The Seven Acts of Mercy and the Seven Sacraments + the closing. This part of the treatment is also very extensive, where - as always in the book - the tight textual part covers an irradiated and memorable multitude of cases under the typological and artistic aspect together. In fact, the presence of the saints is proposed under the narrative aspect, requiring a multifaceted hagiographic capacity, both with regard to the ancient textual sources, which are constantly recalled, and with regard to the related pictorial translations: think of the martyr trials and unfolding, but think also of the exemplary characters - of faith, study, charity, perseverance - that each image of the saints was meant to imprint on believers.

Lucy, after praying at the tomb of St. Agatha the martyr, proclaims to the Judge her own unblemished faith. The various stages of the torture will follow. Many of these tales are referred to by the so-called late Gothic “Legenda Aurea” by Jacopo da Varagine, who compiled the sacrificial lives of more than one hundred and fifty saints and saints, and which the Author keeps well in mind here

The whole story of the Christian communities of the early centuries was marked by conversions and repeatedly terrible persecutions. According to a repeated tradition a Roman emperor (Hadrian?) in the second century AD commanded the torture of ten thousand of his soldiers in Armenia who had converted to Christianity. The persistence of this memory triggered Ettore Omobon’s commission in Venice from Carpaccio for this very unique altarpiece. According to the Church, martyrdom obtains immediate sanctity in heaven

This miraculous privilege, also granted to Saint Francis of Assisi and more recently to Saint Pio of Pietrelcina, totally marks the intimacy of a soul in love with Jesus himself. This Pala guarantees holiness in its various forms: monastic life, study of the Scriptures, preaching, contemplation. Beatifying here is the serene presence of heaven and, likewise, the appearance of Mary with the Child

St. Jerome, who was born in Illyria and died in Jerusalem in the fourth century AD, led a personal ascetic life rich in culture and ancient languages in various places . His fundamental contribution in Church history was the direct translation of the Bible from Hebrew into Latin, and the translation of the gospels from Greek into popular Latin (vulgata). Thus sacred Scripture could become the universal heritage of the Church, which recognized him as a saint and doctor. One legend has it that during his solitude he was able to heal a wounded lion by removing a deep thorn from one of its paws; the animal has remained meekly by his side ever since. But perhaps the lion reflects the anchorite’s very stern character.

The fifth chapter is given to the Mysteries. A very right and conscious choice, since that theater of faith that is formed by the altarpieces (think, for example, of a church with its side chapels and their entire round) contains facts and people, but also divine symbols and dispositions, and also incitements for practical and spiritual life together. The parts of the treatment are: the Opening which sets up the concept - The Madonna of Mercy - The Madonna of the Rescue - The Immaculate Conception - The Madonna of the Rosary - Other Mysteries of the Madonna - The Double Intercession - The Holy Kinship - Mysteries of Christ - The Mystic Mill and the Mystic Winepress - The Most Holy Name of Jesus and the Three Realms - The Trinity - Mysteries and the Monastic Orders - Disputations - The Cross and Other Objects - Myracle-Working Works of Arts. Already the list of these sacred mystical categories assures the Author’s extreme attention and research, which we must here remark; while the same list forcibly exempts us from showing all related examples. As always, the figurative apparatus remains vivid and effective. The identification of the “misteria” takes place on all the choices of the Catholic Church, punctually recalled, and again opens the ways of dozens and dozens of laudatory and impetrative paths.

It is fitting to refer to well-established choices of medieval Christian life with this panel by Memmi, an aristocratic Sienese painter who executed it while the new Duomo, a wondrous shrine for the Corporal on which the Eucharistic miracle of Bolsena (1263) took place, was rising. Here Our Lady appears in the pattern “of Mercy” covering with her cloak a multitude of men and women belonging to a Confraternity dedicated to the relief of the poor and the sick. One may think of the divine Mercy corroborated by Mary, over whom the Angels gaze, but one must acknowledge the merits of those who worked freely and lovingly for the needy. This image belongs to a whole world of similar variants that will persist strongly into the Renaissance

This beautiful panel, still admirable in the church of Santo Spirito in Florence within the Velluti Chapel, is due to an unidentified Master but certainly to a very thoughtful patron who picked up a multigenerational tradition. “Rescue” can be invoked and applied for many situations of real spiritual danger, always resorting to Our Lady, the great victor over Satan. In this scene the child likely represents a soul being rescued from the devil

The composition is complex, paratactic, and stigmata of heterogeneous elements. The office of this canvas, originally placed in the chapel of the convent of San Bernardino in Ferrara, is explicitly to show and hail the Madonna as already holy from conception. Everything here lies in support of that theological reality: the presence of the Trinity, the entire creation, the gathering around Mary of the great Doctors of the Church, the suspended symbols and the thirteen written declarations. The conception of the Mother of God without the shadow of original sin was at that time a subject of discussion, but also of extreme jealousy on the part of a great many believers who peered within the mystery

The large canvas makes explicit the “misterium” of intercession. For the Christian people all grace proceeds from the Father, and to ask Him it is necessary to have recourse to the merits of the Son, crucified for humanity. But the Son always listens to the Mother’s requests, and here is the medium painted here: the faithful ask, the Mother transmits to the Son who is always in relationship with the Father through the Holy Spirit, and so from the Eternal Father graces descend through the way of Jesus and Mary

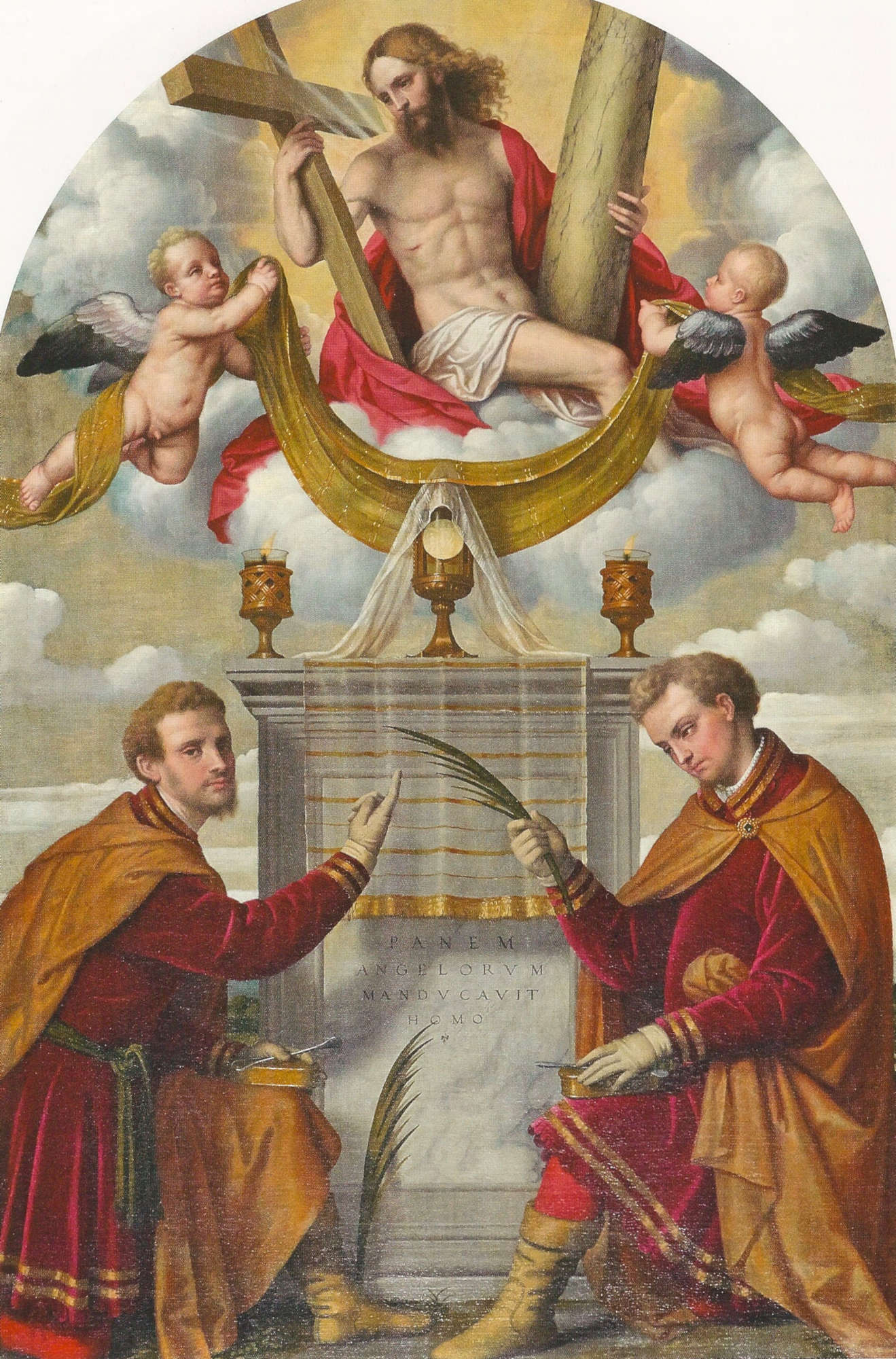

Luminous, almost banner-like drafting, all aimed at validating the bodily presence of the living Christ in the consecrated host. This presence is declared “Panem Angelorum” and in the painting is confirmed by Saints Cosmas and Damian, both doctors and martyrs. The subject is simple and peremptory, strongly affirming the mystery

The sixth chapter is entitled “Narrative and the Predella” and brings together impressive documentation on various works, including predellas of Pale, Polyptychs, and singular compositions. Its parts are: Conceptual Introduction - The Origins and Early Development of the Predella - Narrative Cycles and One-on-Ones - Gold Grounds and Naturalistic Backgrounds - The Predella and the Written Record - Vasari and the Predella - The Decline of the Predella - The Subject Matter of Predellas - The Predella and the Eucharist - Other Settings for Secondary Narratives - Secondary Narratives and Symbols: The Foreground - Supplementary Narrative: the Background - Thematic Extension - Typological Narratives and Fictive Reliefs - The Purpose of the Predella.

With such painstaking, always connected but almost meandering path the Author certainly giants on artistic and content analysis. For this chapter we therefore limit ourselves to just two figurative examples.

Initially in the Basilica of San Lorenzo, the altarpiece celebrates the Anjou family. Here in fact the eldest son, who became a Franciscan then a bishop, crowns his brother Robert as king of Naples. On the iconographic level, this is the first time that a living character appears in an altarpiece, while for us the reading of the episodes of Ludovico’s life takes place in the predella. We must therefore go back to the 14th century, but we know that the use of the predella for the stories of the main character persisted in several cases until the 16th century. Often the “storiette” or other examples also fill the side parts

We see here an excerpt from the very long predella that the master assigned to the young Hercules . As is evident, the impetuous de’ Roberti did not divide the miracles of the saint into separate parts but tied them together with an astonishing continuity, all Renaissance, where every imaginable invention stretches along an endless space but saving the most frank rules of architectural orders, perspective, lights and figurative relationships. A masterpiece well suited for miracles!

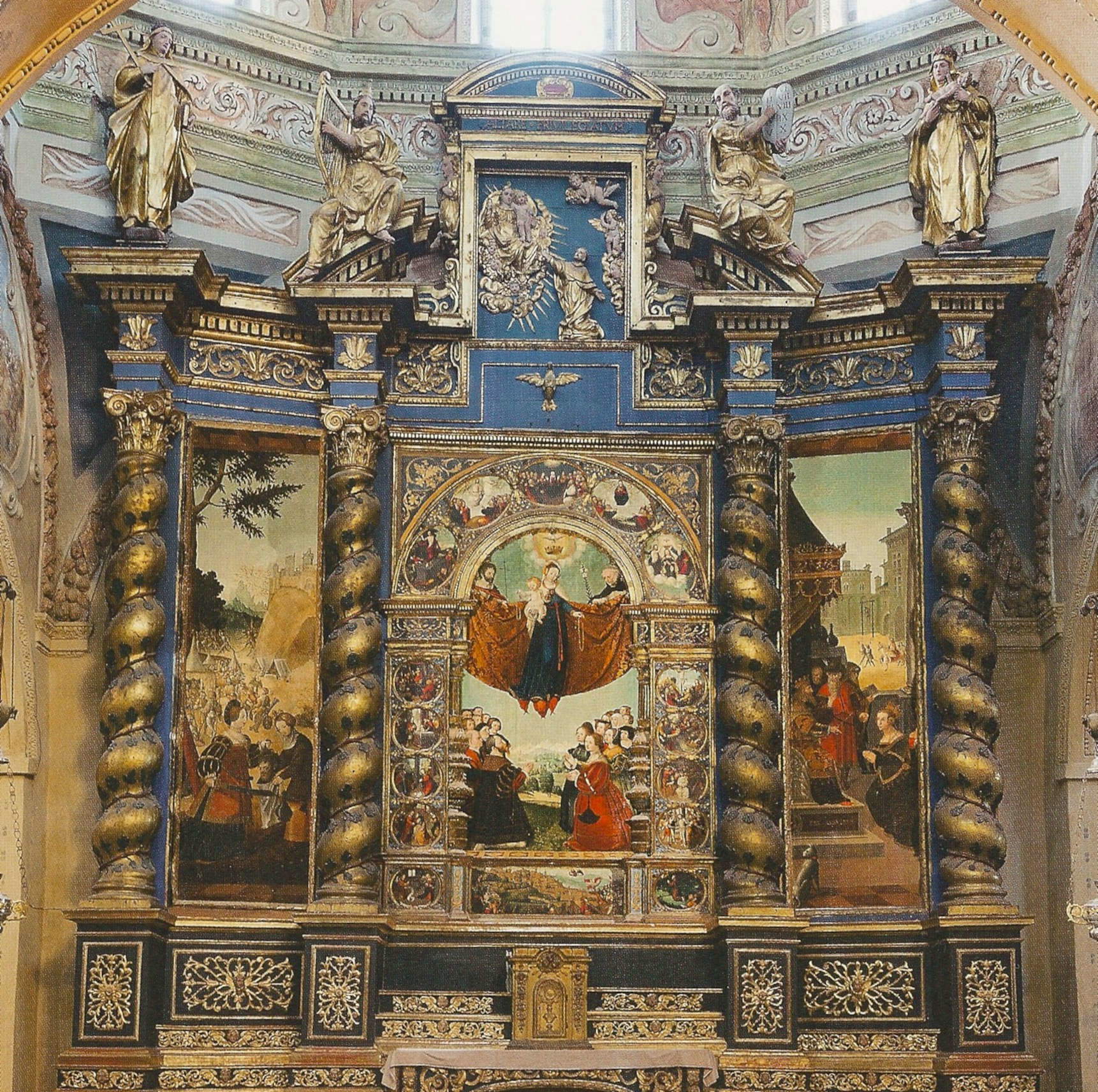

The next chapter, “Frames, Sculpture, and the Altarpiece,” after the opening follows by distinguishing in order: The Manifacture od Altarpieces - Frames and their Contents - Painted Frames - Sculpture around Paintings - Painters and Frame-Makers - Drawings for Frames - Altarpieces and the Third Dimension - Hybrid Altarpieces - Altar-Frontals - The Sculptural Altarpieces. The Author’s careful distinctions and classifications also stand out in his observation of the various resolutions that Italian art made in wall altars. Some grandiose ornamentation in structure appears here, or what we might call the last wooden dossals, but in the classical style and always covered with gold, and then we move on to marble monuments, from Naples to Venice, and to sublime Della Robbia majolica. The story touches on the “hybrid altars” where various moldable materials come together and touches on the theatrical scenarios that prelude the Baroque. We have chosen only two examples in so many heterogeneous presences.

A perfect jewel of the Florentine sculptor that opens up the perspective proscenium in the center and places testimonial figures on the sides with the force of the tuttotondo. The base serves as a narrative predella while the entire architectural framework holds the character of an honorary gateway to the spiritual world

The versatile Piedmontese artist painted and sculpted large glorious altarpieces like this one in various ways, and he did so as well in Finalborgo, Revello, and Staffarda. The choice is extroverted, sumptuous, of almost overflowing language, but still neat. Evidence, among many on Italian soil, of the celebratory, offertory and prayerful enthusiasm of many communities

In Ekserdjian’s large volume the last, very important textual section declares itself as “Conclusion. The Council of Trent And After.” We will spare you the stated parts, but here the author pours out a conceptual and preconceptual summa on visual art as it was before the Council of Trent and as it was formed in the immediate aftermath of the Council, touching on ideas and decrees of high ecclesiastical personalities who provided painters mainly with didactic, pious and emotional directions. A necessary conclusion for the total understanding of the work.

In this composition, the painter participates intensely in the post-Tridentine climate that emphasizes the vicissitude of every human life as a path of approaching God. The final purification takes place in what is called Purgatory, from which Christ’s loving mercy frees souls in grace of the prayers raised to him by members of the militant church: seen here are a deacon, a bishop, St. Francis and Blessed Varani over whom the Holy Spirit hovers.

It is our cordial inclusion. The painting shows how the great painter of the turn of the century had already entered, fervently and lucidly, into the emotion of Christian charity. This central figure of the Triptych of Mercy-already placed in Allegri’s hometown-has been rediscovered and reevaluated in recent times by the Friends of Correggio, receiving the full assent of David Ekserdjian

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.