For more than a decade Cristina Beltrami, like many scholars gravitating to the lagoon, has been concerned with the history of the Venice Biennale, focusing her attention on the complex and not always linear relationship of the first editions with contemporary sculpture: a difficult issue, to be pursued in the folds of the reviews of the time-often only a few lines on the sidelines of the pictorial chronicle-combined with a dogged excavation in the archives of the Asac in Marghera, trying to stitch together into a coherent itinerary an otherwise fragmentary history that has long remained in the shadows because of this. Out of this constant and patient effort comes an important volume such as La scultura alla Biennale di Venezia 1895-1914. A Presence in the Shadows, published for Zel Editions and destined to remain as a crucial point of passage for recovering and regaining a series of detailed histories that moved through the polyphony of episodes and proposals that have characterized the event since its inception, as the Castello gardens were enriched with new national pavilions.

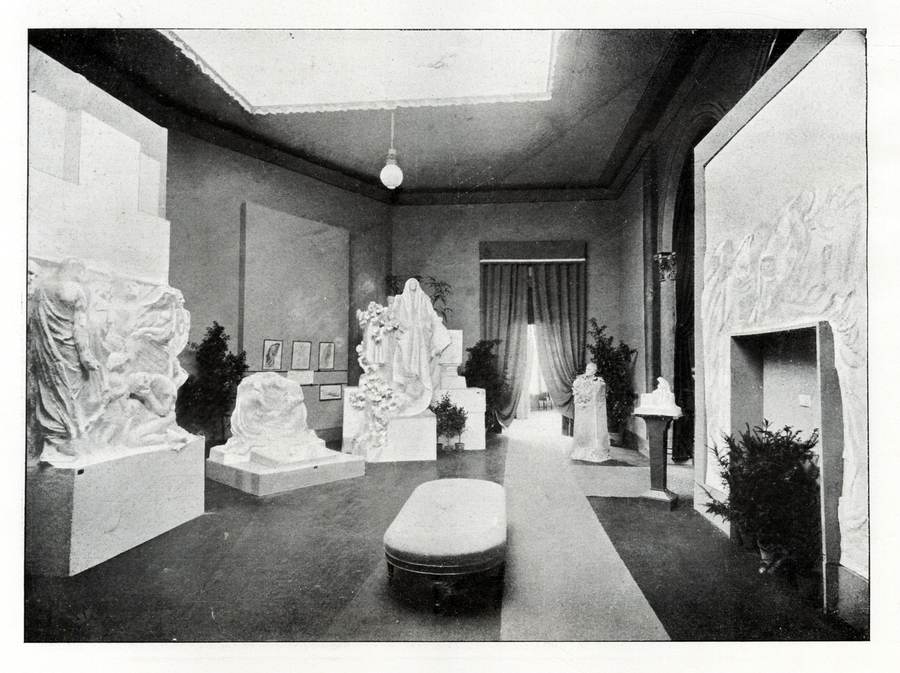

Indeed, Cristina Beltrami has traced with descriptive meticulousness, in a succession of wide fields and sharp focus, the emerging presences and itineraries that the visitor could make from pavilion to pavilion, or room to room, accompanied by a wealth of photographic material that opens up further perspectives for reflection. This is obviously not, nor was it intended to be, a history of sculpture at the turn of thenineteenth century and the first decade of the twentieth century, but a history made up of accelerations and late recoveries, of misunderstandings and rediscoveries that, through the now methodologically tested filter of exhibition histories, returns in filigree problems not only of a formal order, but by approaching the underlying question from angled planes sheds a different light on formal problems as well, in which the very facts of style are carriers of ideological themes. The result is thus an overview of the international presences that animated the first eleven editions of the Venice Biennale, from its inception in 1895 to the outbreak of World War I. Through this backbone, the author has sought to reread the situation, language and perception of sculpture, which remained neglected in studies but a significant seismograph of taste and more complex identity issues. It is also an opportunity, moreover, for a useful stocktaking of studies, questioning the historiography and the emergence in later times of a specific interest: in fact, in France studies on the “academy” date back to the 1980s, while in Italy people began to talk about it in the 1990s, with a crescendo of interest that has led in the last ten to fifteen years to a fundamental increase in this field of studies. Talking about the luck (or misfortune) of sculpture means in fact keeping in mind both the critics and the exhibitions and the place it holds in the spaces of the same exhibition: it is one thing, in fact, to reserve a special space for sculpture, clarifying its borderline nature with the applied arts (as the Victoria & Albert Museum in London teaches); it is another, as in Venice, to mix painting and sculpture in such a way as to establish a dialogue between the two, however much the former later led to a marginalization of the latter in the “Salon-like” commentators. After all, the mortgage placed by Baudelaire on a primitive art, which could not aspire to the same nobility expressed by drawing and color, would resonate for a long time, even where not explicitly mentioned.

There are several ways to go through this book: one can follow one step at a time the physiognomy of each individual event, in its spatial dislocation, imagining what the visitor might have encountered and recalling from time to time the glosses of the hot comments; or one can bring out certain underlying themes that chase themselves from one edition to the next, and of which the rich iconographic apparatus gives implicit confirmation.

The first, and perhaps the most important, is the counting of presences and absences, between artists hailed beyond all imaginable expectations today and others who will instead remain on the margins of the event for a long time. Striking, in this sense, is the case of Medardo Rosso, who will land in the Biennale over fifty years old only in 1914, with an anthological selection of works dating back to well before this event was born: a dutiful and necessary homage, as Margherita Sarfatti would promptly acknowledge, but equally unforgivably late, as Ugo Ojetti would note, and in a strident comparison with the tetragonous virile grandeur of Ivan Mestrovic, who dominated that edition by embodying a monumental and Wagnerian spirit, or with the option of Bourdelle, among the protagonists of the French scene, as crucial as he was neglected in Venice. Until then, in fact, for the profile of international sculpture returned by the lagoon pavilions, Rosso’s pictorial and vibrant option had had no right of citizenship (but compensated by a conspicuous acquisition for Ca’ Pesaro), except perhaps flowing back into a tamed and appeased version through the scapigliate options.

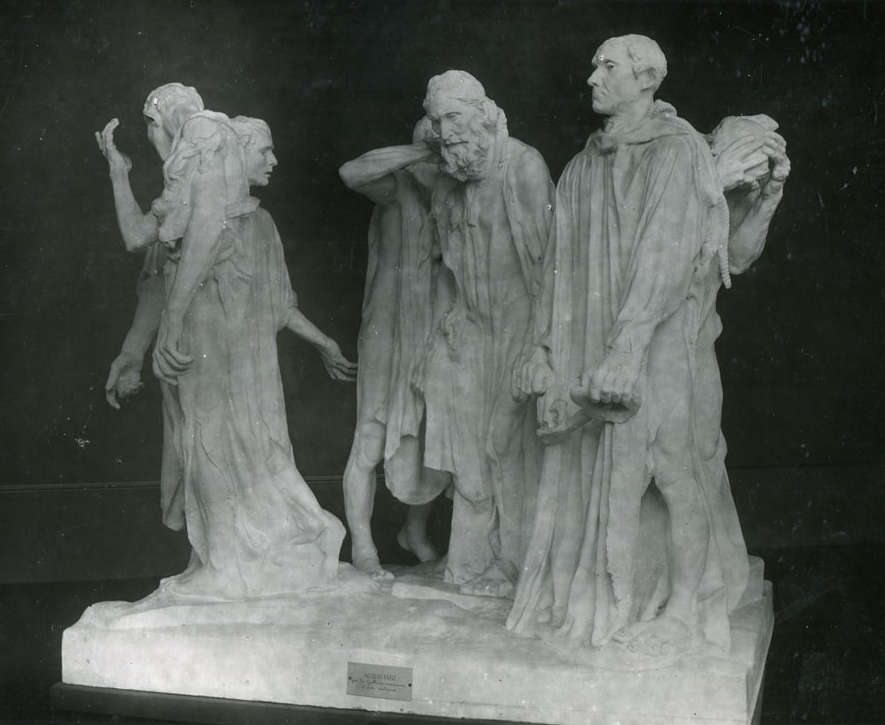

Not infrequently, in fact, the most disruptive novelties arrived in the halls of the Biennale through the reworkings of epigones, in advance of the presentation of the great international masters. This is the emblematic case of the work of Auguste Rodin, for which Fradeletto would have made false papers right from the start, and of which five crucial plaster casts could be seen in the second Biennale in 1897, but which would have a truly detonating effect only in 1901, when ala the Fourth International Art Exhibition came a plaster version of the Bourgeois of Calais, on that occasion acquired by Cà Pesaro. But the “Rodin function,” at those dates, was already circulating currency, and Italian sculptors themselves-as Flavio Fergonzi demonstrated at the time in an essay-guide on the subject-had been able to draw on Rodin motifs and models circulated in various ways. And in Venice itself, over the years, there had been reverberations of that lesson, as if preparing the ground for the coming of the master, through the declinations offered by interpreters who had already come to terms with that rhetorical model. If one tries to put on spectacles to see things with the eye of the time, however, it is Pietro Canonica’s exhibitions that hold sway, on the final bars of this period we see Trentacoste’s retrospective, and regional presences from Francesco Jerace to Carlo Ciusa; while leading the way in the metamorphoses of taste, not without controversy, is Leonardo Bistolfi, the protagonist of a personal room at the sixth biennale in 1905 with the monumental high relief of The Cross, but a constant presence in all editions.

The book deals with a complex season in which sculpture is seeking an international language, but at the same time trying to mediate foreign fashions with tradition. In sculpture, more than in painting, the perpetuation of formal, iconographic and stylistic patterns is hard to die for, and modes inferred from sixteenth-century sculpture - but already push toward later centuries - more or less exaggerated forms of Michelangelism (sometimes textbook, like Emilio Quadrelli’s Rest of Hercules at the III biennale); and finally legacies from diaphanous fifteenth-century grace. Everything is mixed in an eclecticism that is measured by foreigners, and that oscillates between flowery symbolism and more or less stark realism depending on how much they exemplify the real thing. Evidence of this is the theme of the portrait, from the Baroque bust to the Neo-Renaissance (exemplary is Canonica’s Dream of Spring, which from the third exhibition glides into the collections of the Museo Revoltella in Trieste), but even more so it is on the nude that the dialectic between renewal of languages and persistence of models is measured: once freed from religious or mythological disguises, and once the eroticization of those themes is done, something of the ancient masters remains, opening the way to an anecdote in which nudity would not be justified outside the field of sculpture. Why are nudes, for example, the youth of Hannibal De Lotto’sAccident, or Hugo Lederer’s Schermidore, or even more so Urbano Nono’s Tattoo, if not to offer proof of bravura in the anatomical rendering of the figure standing or in motion, amid hypertrophic complexions and muscles calcified on the real thing, and reconnect with the high road of ancient statuary? The terms of grace and classicism are indeed very much in the words of the interpreters, just as the muscular turning of the bodies and the consequent relationship with heroic nudity is problematic. By paradox, it suggests an alternative way to the relationship with reality, and with the abstracted and modernist adaptation, the track offered by Italian and international “animalier” sculptors, with the freedom offered by placing themselves halfway between the statue and the object of decoration, less bridled by conventions and available to certain bursts of whimsy: a zoo in which Diego Sarti’s African lioness (in 1897) found space, August Gaul’s otter in the sixth edition (1905), or Franz Barwig’s pelican and Carl Millés’ jungles (1907), to Imre Simay’s monkeys (1909).

After all, in the Biennale the whole range of possible destinations for sculpture, from monument to furniture object, was squared from the beginning, with a spillover into the techniques and symbolic value of the source material: if bronze and small bronze dialogued with medallistics, in a long duration of ancient humanistic collecting themes, and if marble was not lacking in its austere and impenetrable whiteness, it was plaster that was the real protagonist of much sculpture in the Biennale, with a casuistry that went from the sketch to large-scale sculpture. On the latter, then, a further strategic game was played: there was no shortage of works that hoped, after the passage to Venice, for a translation into a more durable material, with a crucial split between the moment of plastic invention and that of its final translation into marble or bronze (or both at times); but from the halls of the Biennale passed also the plaster casts of sculptures that had already been placed in monumental contexts, or were close to being put in place, as a true anticipation, offering a sampling, or perhaps a diagram of multiple iconographic fortunes, from the evergreen myth of Dante (from Paolo Troubetzskoy’s sketch in 1897 and Alfonzo Canciani’s in 1899, to Carlo Fontana’s Farinata in 1903) to the heroes of ancient Rome or of themodern age( Davide Calandra’sIl conquistatore also holds court in 1903), to the commemoration of contemporaries and the kaleidoscope of narrative and allegorical modes of funerary art. The “difficulties of sculpture,” which would accompany the entire twentieth century, were already all there.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.