The ceramic art of Enrico Baj in a volume that reveals its ironic and experimental side

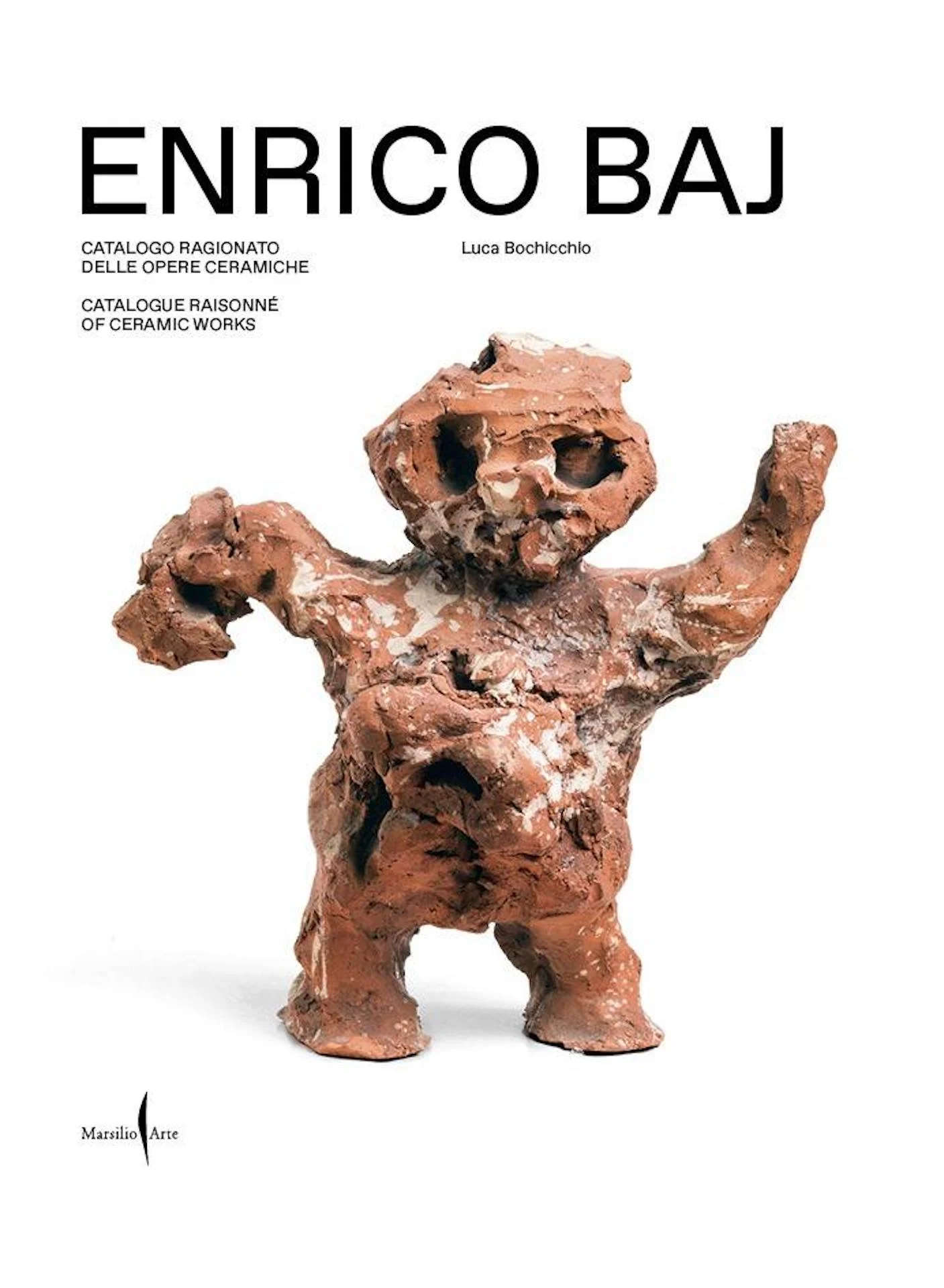

Ceramics, a material that is shaped and transformed under the artist’s hands, is an element that plunges its roots into the past, between craft and art, between its everyday utility and aesthetic expression. And it is in this space that the artistic journey of Enrico Baj (Milan, 1924 - Vergiate, 2003), a twentieth-century painter and sculptor who was able to unhinge the canons of ceramic tradition to make it a ground for free and provocative experimentation, is located. In fact, Baj’s art is distinguished by the extensive use of his innovative techniques, which range from assemblage to the reworking of images and materials of all kinds; the result is therefore new, diverse works that hark back to the progressive creativity of the second half of the twentieth century. In this light, in the volume Enrico Baj. Catalogo ragionato delle opere ceramiche (272 pages, 40 euros, ISBN 9791254631850), published by Marsilio Arte, scholar Luca Bochicchio, the author of the volume, gives us a detailed look at a lesser-known but at the same time engaging aspect of Baj’s artistic production: ceramics, precisely.

Through documentation and meticulous critical analysis, Bochicchio, scientific director of the MuDA in Albissola Marina and curator of the Museum of Ceramics in Savona, guides us to discover a path that represents the playful, visionary and experimental nature of the artist. Baj’s ceramics, full of symbolism are thus a synthesis of memory and innovation. Not only, then, a scholarly tool such as a catalog raisonné normally is, useful mostly to scholars and collectors, but also a book intended for those who, more generally, intend to learn about a perhaps lesser-known aspect of Baj’s production. A bilingual publication, moreover: the texts are in Italian and English.

In any case, ceramics is not a linear element in the Milanese artist’s career: in fact, it emerges as an intermittent presence, tackled with passion and dedication at specific moments of his artistic life. Among his creations, Bochicchio recalls three two-faced sculptures kept in the entrance of his own home. In this case, the figures equipped with eyes, mouths and noses also sculpted on the back of the head, represent a polyhedral nature based on the complexity of the human being. Baj himself, in an interview in the 1980s, declared that the artist’s task is to leave a trace, however tenuous it may appear. Here: those figures, those two-faced Giani fully respond to Baj’s mission and statement. They ideally link up with the footprints left by more distant ancestors.

In tracing the master’s ceramic years, moreover, Bochicchio dwells on the chromaticity of the majolica made in Faenza by Baj, and inspired by his kitsch period. Despite their beauty, what is attractive about the works is found in the crowd of faces that support them. They are figures charged with human frailty. Baj thus confronts themes such as contemporary society, myth, identity, and uses ceramics as a tool for critique and reflection. And certainly his ability to combine the grotesque with the sublime makes his ceramic corpus one of the most original demonstrations of twentieth-century art. The artist thus had the ability to adapt his poetics to ceramic materials and techniques, and his various experiments demonstrate this: his approach to terracotta in Albisola in the 1950s (it was here, in Liguria, that Baj conducted his first experiments: these were mainly relief panels, plates and figures in the round), the majolica made in Faenza and Imola in the 1980s and 1990s after almost thirty years without touching the clay material (the artist, when asked, said that he was first and foremost a painter and had for these reasons suspended his research on ceramics), and the final productions in Castellamonte. “The approach to ceramics,” Baj would have said in the 1980s, “has always been totally spontaneous for me, that is, in accordance with my sensibility and my way of making art. I love the material very much. I do and have always done material painting, preferring the technique of collage, that is, the insertion of objects and materials having their own weight and identity.”

The volume thus simultaneously addresses two aspects: there is obviously a technical cataloguing of the works, but also the placing of these works in a broader historical and cultural context. All this highlights Baj’s dialogue with the great artistic movements of his time such as Surrealism, the CoBrA group, but also the pataphysics of Alfred Jarry.

It is precisely linked to the figure of Jarry, in the second part of the twentieth century that the Milanese sculptor made numerous ceramics inspired by the play Ubu roi, drawing on the pataphysical imagery of Alfred Jarry, a French writer born in Laval in 1873 and known for having developed the science of imaginary solutions, called precisely pataphysics. Among the artist’s works is an important work such as The Stories of Ubu made between 1983 and 1985, which not only represents Baj’s creative and experimental genius, but above all becomes a tool for dealing with the difficulties of contemporary life. The irony and absurdity that characterizes Ubu is transformed into a remedy to the rigidity of reality and presents imaginary solutions toward what are the darkest moments in everyone’s life.

In recounting Baj’s art, however, Bochicchio does not fail to pay homage to the skill and experience of Faenza-based ceramists such as Davide Servadei, whose skills (technical and physical) were instrumental in translating Baj’s visions into reality. What then is the central theme of the catalog? Definitely Baj’s relationship with Italian craft workshops, considered the true centers of excellence where the artist found the basis for his experiments. Not being a traditional ceramist or a specialized technician, Baj always collaborated with master ceramists such as Servadei, who in his case guided and assisted him in the realization of his visions.

Tied to the expertise toward the assembly and disassembly of the works are recalled by Bochicchio two particular moments related to the setting up of several installations. The one in 2001 on the occasion of the retrospective on Baj at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome, characterized by the instability of the installation of La Bella e la Bestia, with the risk of the work’s collapse, and the one in 2003, during the installation of I funerali dell’anarchico Pinelli in the Sala Napoleonica in Brera, in which the setters climbed on a very high and unstable scaffold. In both cases, the delicacy and importance of the ceramics required meticulous work.

The volume, released at the end of 2024 on the occasion of a double anniversary (the 100th anniversary of Baj’s birth and the 70th anniversary of his first ceramics, made in Albisola in 1954), also delves into a not insignificant theme: the comparison between Baj and well-known ceramic masters, including Lucio Fontana. Although both chose matter as their expressive medium, Fontana, known for his cuts on canvas, used ceramics to flesh out the vision of his spatial concept. Through works such as Concetto spaziale of 1954, he used ceramics in the same way as canvas and imprinted violent, energy-laden gestures into the material to create a tension between control and chaos. Baj, on the other hand, has interpreted ceramics in completely distinct ways, through effects that express his playful nature and willingness to overturn the traditional rules of ceramics. Baj tells stories, evokes myths, and constantly mocks the dramatic human condition.

What, then, are Baj’s ceramics? How can we explain their meaning? Baj’s works are fragments of a poetics that combines play and depth, lightness and commitment, myth and everyday life, tradition and experimentation. And the Catalogue raisonné of ceramic works analyzes the eclectic and visionary dimension of an artist who struggled against the boundaries between art and craft. The catalog is therefore aimed at scholars, enthusiasts and the curious and presents a journey through ceramics as a metaphor for the life and thought of Enrico Baj, an irrefutable master of the 20th century.

|

| The ceramic art of Enrico Baj in a volume that reveals its ironic and experimental side |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.