The best of Baroque Genoa in a beautiful and insightful book

Among the most interesting book releases of 2022 is an important work dedicated to the Baroque in Genoa, designed for a wide audience: this is Genova barocca. Works, Artists, Territory, edited by Giacomo Montanari, a book published by Genova University Press (228 pages, 25 euros, ISBN 9788836181537), and which right from the mode of distribution makes manifest its intention to aspire to reach as many people as possible and to position itself as a tool that places the reader at the center. Indeed, the book is published in open-access mode for the e-book version: those who want to read it in pdf mode can simply download it from the publisher’s website.

The volume is constructed as a true guide, cultured and of a high standard, to the discovery of the treasures of seventeenth-century Genoa, along a time span that covers the entire Siglo de los genoveses, to use the fortunate expression made famous by Fernand Braudel, that is, from 1605, the date when the great Pieter Paul Rubens fired the Circumcision for the Gesù church, to 1755, the year of Francesco Maria Schiaffino’s Saint Anne : we thus go from the Flemish painter’s arrival on the shores of the Ligurian Sea to a period about forty years before the fall of the Republic of Genoa in 1797. The volume is decidedly orderly and composed with stringent criteria: one work for each artist, so as to give an idea, at the same time, of the extreme variety of the Genoese artistic panorama along the one hundred and fifty years examined by Genova barocca, and of the heads of work of the individual artists (whose production, however, expands far beyond what is presented in the book, which therefore also comes across as a genuine invitation to discover all that seventeenth-century Genoa has to offer).

There are many merits to the publication, starting with the fact that the volume, although an academic product in every way, wants to open itself up to the outside world: thus not a publication for insiders, but a guide that accompanies the traveler in his stay in Genoa by providing suggestions on its places to see and on the artists to meet (and, why not, a guide for the citizen himself as well: Baroque Genoa is not only a knowledge tool for those from outside, but also, and perhaps especially, for those who live in the city and want to learn more about its heritage and history). And that it is a true guide rather than an academic title is evident first and foremost from the style employed: although the approach is that typical of high-end art publishing rather than that of tourist publishing, the slant adopted in the enunciation is marked by clarity and freshness, and each of the cards presenting the works literally guides the reader to an understanding of the works of the artists who were active in Genoa in the seventeenth century. Indeed, the volume lingers a great deal on descriptive details, as if to guide the viewer’s gaze in correctly viewing the painting. There is, of course, no lack of information of a historical nature or relating to collectors’ passages: however, Baroque Genoa is, if anything, more concerned with recounting the historical dynamics that led to the birth of the works analyzed than with the history of the paintings and sculptures tout court. What emerges, therefore, is an interesting fresco on the Genoese seventeenth century, examined from the perspective of the visual arts, which will fascinate both those who will find themselves facing this history for the first time, and those who already know it and wish to have a different, more “welcoming” reading of it, so to speak, in the knowledge that what the book offers the reader is but a glimpse of the events of that era.

Curator Giacomo Montanari is perfectly aware of this: in the book’s introduction, he calls the volume “deliberately partial” and stresses that “it is impossible to summarize a complex phenomenon such as the cultural and artistic life of a city, extended over the space of a century, in a single book.” Here, then, is the explication of the criteria according to which seventeenth-century Genoa is presented to the reader: through the dynamics of the visual arts, in the awareness that paintings and sculptures are but a “tessera,” says the editor, of that mosaic that should take into consideration so many other areas, from economics to cuisine, from literature to customs. The belief is that “Through the reading of artistic artifacts, be they pictorial or sculptural, it then becomes possible to open a window on a reality different from our own, guided by the choices of the artists and the wishes of the patrons, extraordinary receptors of the tastes, passions, tragedies and stories of vanished societies. The work of art plays, thus, the role of document: its reading accompanies to understand the contexts and - at the same time - receives from the context meaning and significance.”

Another of the reasons behind the publication of Baroque Genoa is that if institutions (in this case the university) and communities come together, commendable initiatives that strengthen public awareness, heritage awareness, can result: one thinks not only of the exhibitions that are organized every year in Genoa, but also of the achievement of certain goals, first and foremost the entry in the Unesco World Heritage List, which benefit the whole fabric of the city. A heritage that works, a known heritage, a shared heritage is an important lever for the cultural, economic, and social progress of a city: “if the past aspires to be a guide in acting in the present and - even - to be able to be used as a compass to plan the future, it is necessary that it be known, understood and made one’s own,” Montanari stresses. A book, then, as tangible proof that art history is not just a subject for insiders or a subject for school study, but is a living language, a common language that can speak to as many people as possible. “An art history that is increasingly shared, increasingly available to all through ensuring a close relationship with scientific studies, offered to the community,” is the curator’s thesis, “is also the key to the redevelopment of territories, urban and suburban.”

As for the treatment, it was anticipated that it is constructed by tabs, each dedicated to one of the important works of the seventeenth-century protagonists present in the city. Those hoping to find there theEcce Homo from Palazzo Bianco, about whose Caravaggesque autography doubts have begun to grow more insistent since the discovery of theEcce Homo Ansorena last year, will probably be disappointed, but the other “textbook” names are all there: they range from Rubens’s Jesus, which opens the list of fifty masterpieces (this is the number of works presented), to Orazio Gentileschi’s splendid Annunciation in the church of San Siro; they go from Antoon van Dyck’s sumptuous Portrait of Anton Giulio Brignole Sale to Guido Reni’s airy Assumption of the Virgin , also in the Gesù church, or Guercino’s unforgettable Cleopatra in Palazzo Rosso. In between, a vast theory of wonderful works, and we are not just talking about those kept in museums or churches. One may be astonished to learn that, inside a university building, one can stand in admiration looking at the frescoes in the Gallery of the Rape of Proserpine by Valerio Castello, in the heart of Palazzo Balbi-Senarega now the seat of the Genoese university, or that inside the headquarters of a bank (but which in ancient times was a splendid noble residence) is one of the most lofty frescoes by Domenico Piola. Not to mention, then, the unexpected encounters: who would imagine finding a work by one of the greatest Dutch masters of the 17th century, Gerrit van Honthorst, inside a sober and almost hidden church like St. Anne’s? Who would think that in an even more modest-looking church, moreover in the suburbs, such as that of Sant’Ambrogio in Voltri, hides a treasure chest containing an early masterpiece by Bernardo Strozzi?

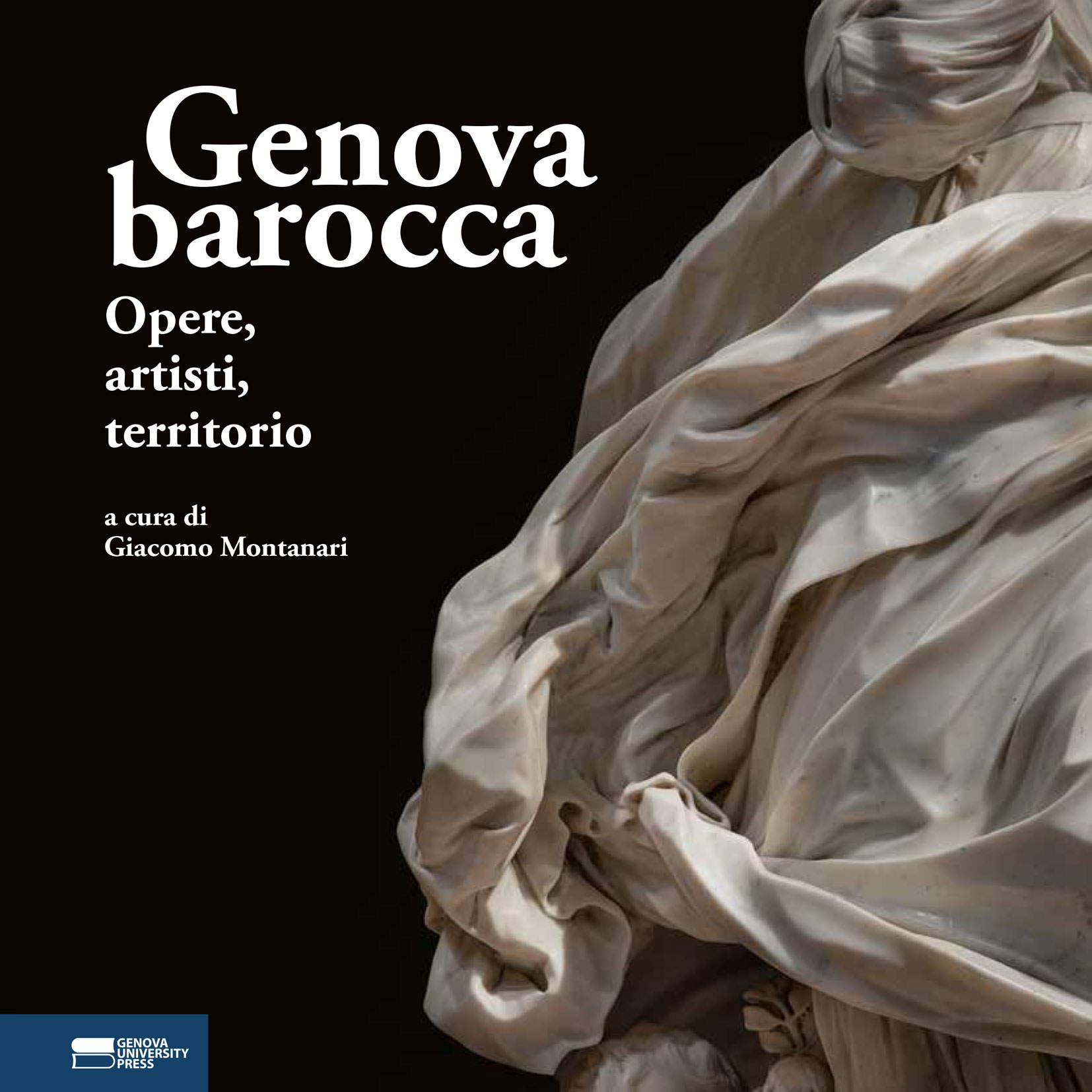

All fifty entries are signed by young scholars: in addition to the curator, Matteo Capurro, Giorgio Dellacasa, Ambra Larosa, Fabio Obertelli, Margherita Orsero, Martina Panizzutt, Pietro Toso, and Beatrice Zulian took turns writing the texts. Another point of merit are the excellent photographs taken by Fabio Bussalino, Laura Guida, and Luigino Visconti. A high quality work, in essence, not to be missed.

|

| The best of Baroque Genoa in a beautiful and insightful book |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.