News and unpublished aspects on Giulio Romano in Mantua in Stefano L'Occaso's new book

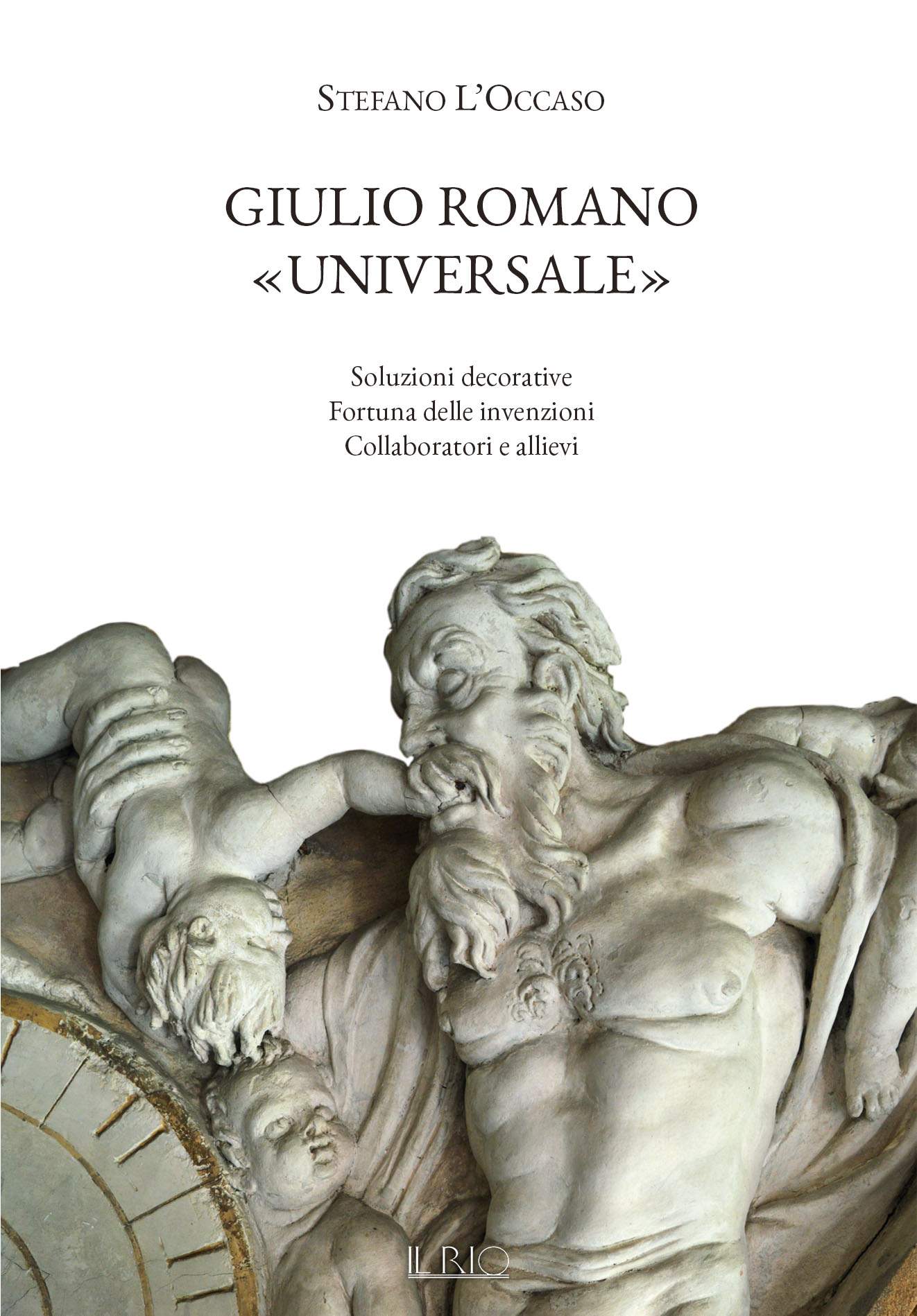

“This book dedicated to Giulio Romano extols his creative virtues and suggests some paths, between beaten and new ways, to reconstruct his immense fortune. Starting from Mantua, such a work, asystematic and even humoral, cannot compensate for the lack of an up-to-date monograph, since the only essitent that examines the artist at 360 degrees is Hart’s, which, however, dates back to 1958. This work is valuable for its capillary analysis of the artist’s production, its rich iconographic apparatus, its documentary registry, and its list of drawings then known, but it is obviously dated and, above all, almost unobtainable: the two volumes of the work are offered on the Internet at dizzying prices.” It is by posing the problem of an up-to-date monograph on Giulio Romano (Giulio Pippi de’ Iannuzzi; Rome, c. 1499 - Mantua, 1546) that the book Giulio Romano “universal,” a challenging work by Stefano L’Occaso, art historian, restorer, former director of the Polo Museale della Lombardia, and expert on 16th-century Mantuan art, opens.

The volume, published by the Mantua-based publishing house Il Rio, starts from the awareness that, while it cannot yet fill the gap of a new monograph on the great artist, there are some areas of study on Giulio Romano’s art that require updates that cannot be postponed until a later date. The focus of the book, meanwhile, is narrow: it deals exclusively with what Giulio Romano did in Mantua, from the date of his arrival in the city (1524) until his death that occurred in 1546 (the Roman years are therefore excluded). But these are years in which Giulio Romano did so much: think only of the construction sites of the Ducal Palace and Palazzo Te, or of the many undertakings that the artist followed in the city, beginning with the works in the Albertian basilica of Sant’Andrea or Giulio Romano’s house in the contrada dell’Unicorno, not to mention the many altarpieces that Giulio and the artists of his workshop left in churches in the present province of Mantua, from Curtatone to San Benedetto Po, from Nuvolato di Quistello to Felonica. Some chapters are also devoted to enterprises outside the province (i.e., outside the Gonzaga duchy): the presbytery of Verona Cathedral and the decorations of the basilica of Santa Maria della Steccata in Parma and that of Santa Maria di Campagna in Piacenza are discussed.

For each of the interventions that ancient sources recall as having been executed by Giulio Romano, Stefano L’Occaso questions the extent of the achievements of Raphael’s great pupil, sifting through the most recent critical hypotheses, and traces clear paths within Giulio Romano’s own art: the building site of the Polirone monastery in San Benedetto Po, for example, represents the debut of plastic decoration in stucco, which starting shortly after this date, the author writes, would “prevail over pictorial decoration in the remaking of the city cathedral, the extreme work of Giulio Romano.” And again, in the Boschetti chapel in Sant’Andrea (work on which was completed, according to the author, in 1536), L’Occaso identifies the starting point “for the decoration of all the other chapels of the Albertian basilica, painting the side walls with two vast unitary scenes and allocating an altarpiece on canvas to the back wall.”

Particularly rich are the two chapters devoted to the great Gonzaga construction sites, those of the Ducal Palace and Palazzo Te, which include information and hypotheses not only on the works themselves, but also on how the work proceeded. It is therefore interesting to note what L’Occaso writes about how Julius structured his undertakings: “Julius directed his construction sites for both the construction and decorative phases, with a notable caesura (in my opinion) in the treatment of exteriors and interiors: if the former live by their architectural strength, the latter are instead built and realized to accommodate the decorations, and the architectural aspects are often subordinate to the decorative ones. The solutions adopted underwent enormous variations within a few years, with a gradual abandonment of the more traditional ones of the 15th century.” Continuing, L’Occaso recalls how Giulio Romano brought to Mantua the experience he had gained in Raphael’s workshop in Rome, conducting his own building sites and their design phases in the way Raphael conducted his own: posing himself as a prolific and “volcanic” inventor who produced a vast volume of drawings, useful primarily for their practical purpose than as completed works (this also explains the thefts of drawings that the artist suffered, and the concern of Duke Frederick II, who feared that the master’s ideas would spread outside his domain), which were very rapid because of the pressures of patronage (L’Occaso notes, for example, that in Julius “usually lacks the phase of detailed study of the figure, which normally follows the sketch [.... and precedes the model,” a lack perhaps due to the need to “speed up the creative process”), Giulio Romano initiated work that was then divided among highly specialized collaborators devoted to different tasks (there were those who concentrated on figures, those on landscapes, there were gilders and plasterers, and so on).

The pages describing Palazzo Te follow an essentially chronological order and focus on the historical, stylistic and technical aspects of the building site, glossing over the content aspects, which are already covered extensively in the previous bibliography: the example of the Camera di Psiche is worth mentioning, where we focus almost exclusively on the stylistic and technical innovations made by Giulio Romano during its realization. On the level of style, L’Occaso observes how Giulio Romano dealt with foreshortenings on the ceiling, that is, with a “personal solution that later had great fortune, especially in Venice”: it was “a matter of painting a surface in which the representation takes place on a false plane inclined forty-five degrees with respect to the plane of the ceiling, with a compromise that in essence maintains the illusory character of the foreshortening, while favoring the legibility of the scene. He experimented with this planar rotation precisely in the room of Psyche, where the center of the vault is in perfect foreshortening, while the octagonal and semi-octagonal scenes placed around it are precisely treated with a variable inclination but close to forty-five degrees, since the privileged point of view from the center of the room is not zenithal but oblique.” From a technical point of view, we focus on the technique of theincannucciata used by Julius perhaps for the first time in northern Italy: this is a technique, described in Vitruvius’s De Architectura (which the artist was therefore familiar with) that involved the use of reed mats covered with plaster as a support for the room’s lacunars, painted in oil. The same innovativeness was later to be found in the celebrated Chamber of the Giants, which, the book’s author writes, “offers one of the first, complete and conscious abolitions of Vasari’s ’partimenti,’ as Jacopo Strada had already remarked (’in tutta una volta senza veruna cornice e ornamento’).”

Even for the works in the Doge’s Palace, the perspective mainly concerns the innovative aspects, as well as the terms of Giulio Romano’s interventions (and what remains of them). The example of the Sala di Troia, whose novelty, destined to “set the standard” as L’Occaso assures, is the unification of the entire decoration of the vault of the room “erasing the architectural lines and connecting all the variants of the view in a single imposing purely empirical orchestration of space,” is worth mentioning. Contrary to what Michelangelo had done in the vault of the Sistine Chapel, in the Trojan Room Giulio Romano does not admonish predefined viewpoints, but suggests “a fluctuation of viewpoints, a multiplication and hollowing out of spaces and depths.”

One of the most interesting novelties introduced by the book is the look at Giulio Romano’s pupils: for the first time, their experiences are all ordered in a volume that recounts their biographies, major works, and relationships with the master. With a perspective that does not omit judgment: studying Giulio’s pupils, L’Occaso explains, “does not mean falling blindly in love with them. Their inadequacy emerges especially during the 1930s following the departure of Primaticcio and Pagni, with whom the quality remains on a high average. In the fourth decade, moreover, some of his pupils tend to provide a caricatured version of the master’s art: this is the case with Rinaldo Mantovano, the author of the paintings of the chapel of San Sebastiano in Sant’Andrea.” The pupils whose experiences are collected in the book are the aforementioned Rinaldo Mantovano, Anselmo Guazzi, Agostino da Mozzanica, Fermo Ghisoni, Ippolito Costa, Luca da Faenza, Lucas Cornelisz, Benedetto Pagni, Giovanni Battista Bertani, Filippo Orsoni, Pompeo Pedemonte, Bernardino Germani, Simone Bellalana, and Giovanni Battista Scultori. And again, another important new feature is the examination of how Giulio Romano’s fortunes would spread in Italy.

Given the rhapsodic (but extremely orderly) nature of the book, it is difficult to summarize all its themes in a few lines: it is, however, a very dense and demanding work (nearly four hundred pages), and one that, by the scholar’s own admission, takes the form of a bit of a list of “study notes,” a bit of a set of “cores in the artist’s kaleidoscopic production,” and above all as a “sincere manifestation in the face of his pyrotechnic inexhaustible genius.” And because of this nature, the valuable book focuses, as anticipated, mainly on the lesser-known, little-studied or unpublished aspects of Giulio Romano’s production, referring for further study with an extensive bibliography placed at the conclusion. Giulio Romano "Universal “ is available on all major online bookstores and in many ”physical" bookstores.

|

| News and unpublished aspects on Giulio Romano in Mantua in Stefano L'Occaso's new book |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.