If paintings could talk, they would say fewer jibes than their creator

If we were to try to enter any bookstore today, we would find the literary labors of Stefano Guerrera (the one from “If Paintings Could Talk,” the Facebook page where he publishes pictures of works of art accompanied by nice - or at least such in the intentions - captions in Romanesque) in the section most suited to them: that of comic-demotional books, where Guerrera’s titles are in the company of all the other volumes produced by his fellow laughing Facebook phenomena, the ones that are so fashionable. But I can assure you that when Guerrera was still relatively little known (at least outside the web or the circle of his followers), I happened, once, to catch sight of his first book in the shelves devoted to art history. That’s right: the bookseller had placed Guerrera along with Panofsky and Gombrich. And, actually, I think he had a point, too.

And not only because the vaguely Spanish-sounding name of this cheerful, easygoing facebookist sounds so much better than the names those who study art history are used to. But also because, and perhaps we haven’t quite figured it out yet, Stefano Guerrera really is a profound genius in art history. I understood this truth, which we will have to learn to accept, after reading aninterview with the new luminary of the subject in a scientific magazine, namely GQ, in which Guerrera enlightened us with the fundamentals of his art-historical method. “I intuit meanings that the darte experts with their cultural background and method of analysis cannot technically see,” the infallible Guerrera scolds. I think of poor Warburg, who had traveled halfway across America, eating, sleeping and living for months with the natives, to understand how images (and their meanings) were able to survive over the centuries: it would have been enough for him to position himself in front of the Knight of the great Doménikos Theotokópoulos (i.e., El Greco) and have him utter a phrase like “I swear I’m not a faggot” to intuit meanings that he, as an expert, “technically” could not see. And again, pressed by GQ on the philological point of view of his method, Guerrera responds that “for me it is fundamental to always indicate the author and the year in which the work was created otherwise it is just a hilarious outburst that leaves nothing behind.” Eitelberger out of the way: the new frontier in the philological study of works of art is Stefano Guerrera. Simply pointing out author and year is enough to provide an impeccable reconstruction and, above all, to “leave something” for the barbaric and uncultured public, which after the publication of Guerrera’s books will surely have stormed museums all over Italy.

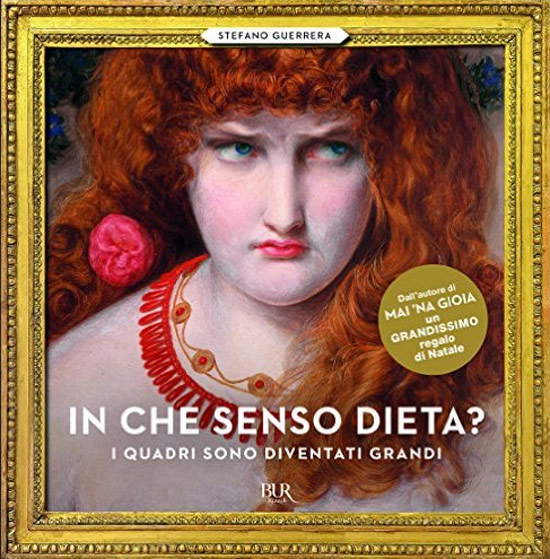

So, could Guerrera’s summation not be adequately summarized in a dense new release? Obviously not, but this time is different, which is why we decided to cover it. The fact is that, in his new book, Guerrera has not merely done what he does best, which is to endow the paintings with silly captions. No: perhaps so as not to cause irreparable shock to readers not yet accustomed to such modern and innovative methods, Guerrera wanted to indulge in that antiquated and nefarious practice of commenting on the work of art. In his new book, titled In What Sense Diet (published by BUR - Biblioteca Universale Rizzoli, €14.90, on sale at the best bookstores, including online: yes, a genius like Guerrera’s is in dire need of publicity, and we don’t ask him for a single lira), the paintings shrewdly chosen by our man no longer sport only author, title and date, but are also provided with commentary of the highest order. There is only one small, negligible problem: Guerrera’s comments are chock-full of jibes, even elementary ones. But just chock-full. Trying not to get lost among the wagonloads of Victorian-era artists to whom Guerrera would seem to accord predilection, I wanted to read some of the comments on works by artists with whom I am most familiar. Before doing so, however, I carefully flipped through the first and last pages of the book, looking for the name, if any, of an art historian (yes, the old-fashioned, dusty, useless kind) who had collaborated on the texts. But, of course, of collaborators there is no trace at all: the comments seem to have been written by the hand of Guerrera, who therefore, on this occasion, also plays the role of a refined popularizer.

But that popularization as we have always understood it is something outdated is evident, precisely, from the branded errors that abound in the book, moreover strategically launched close to the Christmas holidays, like any self-respecting masterpiece of trash literature. Useless to turn to an art historian if he or she “technically fails” to intuit the deeper meanings of the figurative text, and useless even to delve deeper if the goal of the commentary is, arguably, to mitigate the revolutionary scope of Guerrera’s method: a glance at Wikipedia is more than enough to draft serious commentaries. Like the one that accompanies a work by Bronzino, the Portrait of Piero de’ Medici: only Guerrera blatantly mistakes Piero di Cosimo, that is, the father of the Magnifico and the real subject of the portrait, with Piero di Lorenzo, who was instead the Magnifico’s son (indeed: in the commentary, Guerrera even takes care to point out that the Gottoso was the grandfather of what he thinks is the painting’s protagonist!). Still, getting the right Piero right (there was a 50-50 chance) was not even that difficult, all one had to do was read Wikipedia better. But these are obviously trifles, just like moving a painting attributed to Leonardo da Vinci’s workshop (the Louvre’s Bacchus ) to 1695, which was actually done at least one hundred and eighty years earlier. Or how to think that Carlo Dolci was at a standstill between 1673 and 1675 because of a “painter’s block” (the term Guerrera uses is borrowed from Wikipedia itself, the only source to use such an expression: ours probably considers it reliable without the need for recourse to third-party feedback ... is this practice afferent to his method?), when in fact even during this three-year period the artist, albeit at a pace that was far from sustained, continued to produce (perhaps his most famous self-portrait dates from 1674).

And one could continue with a reference to a scholar known to anyone who has even casually opened an art history book, namely Mina Gregori, whom Guerrera, for the occasion clerk of the registry office, transforms into Milena Gregori, or with an analysis of a self-portrait by van Gogh, an artist who, according to Guerrera, “took to portraying himself always the same profile: the one with the ear”: and in doing so, our reckless improvised popularizer expunges all his portraits with the bandaged ear from the Dutch artist’s catalog. One last gem: Guerrera discovers (or invents?) a new hitherto unknown movement, 16th-century Flemish Surrealism, of which the uninhibited commentator even detects a tradition, in this case begun with Bosch and continued with Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

To make a long story short, gentle readers: do you want to give your friend or relative an excellent art history book? Go to your trusted bookstore, sling yourself to the trash department where a volume as far from waffling and abortive as In What Sense of Diet was inexplicably included, forget about such transient phenomena as A regà bongiorno by “er Faina,” and choose an author who is more sincere, more humble and less constructed, and who does not pretend to be an expert at all on a subject he does not know: Stefano Guerrera. A far from awkward and clumsy narrator of absolutely unpatched histories of art.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.