How did Van Dyck paint in Genoa? Michela Fasce's book explains.

The Genoese sojourn of Antoon van Dyck (Antwerp, 1599 - London, 1641), a great Flemish painter and leading figure in the arts of the 17th century, dates back to the 1720s, which has been the subject of recent studies, including those of the restorer and art historian Michela Fasce, who specializes in the diagnostic investigation of ancient works.art historian Michela Fasce, a specialist in the diagnostic investigation of ancient works, who has dedicated to Van Dyck’s Genoese production a project aimed at delving into his painting technique precisely through the scientific analysis of his paintings. Sixteen paintings were examined by Fasce: the results were presented at a conference held in March 2022 in Bruges and published in a volume entitled Antoon van Dyck genoese. Technique, Design, Development, published by Il Geko Edizioni ( 110 pages, 15 euros, ISBN 9788831244701), with a preface by Maria Clelia Galassi and an introduction by Claudio Benso.

The volume begins with a quick reconstruction of Van Dyck’s Italian sojourn, who was based precisely in Genoa, where he arrived in 1621, although according to more recent studies the landing in Liguria should be postponed to 1623: during the period he remained in Italy, Van Dyck visited Rome, Venice, Palermo, Mantua, Turin and Florence, and in all the cities he touched, the artist had the opportunity to come into contact with wealthy patrons for whom he began to paint numerous portraits, some of which are among the pinnacles of his production. Van Dyck thus arrived in Italy rather young, though not entirely inexperienced: inevitably, in Italy he had the opportunity to fine-tune and deepen the painting technique he had learned in Flanders, where he studied with Hendrick van Balen and Jan Bruegel the Younger, and then became an assistant to Pieter Paul Rubens. Michela Fasce’s study focused largely on paintings executed by Van Dyck during his stay in Genoa: ten date from this period, two are from the Antwerp period and four are works in the collection of the Galleria Nazionale di Palazzo Spinola in Genoa, which should be attributed to a follower.

We have in-depth knowledge about Van Dyck’s technique, not only because his works have been much studied and subjected to scientific analysis, but also because there are seventeenth-century manuscripts in which the process is set out in a decidedly clear manner (an important source for learning about Van Dyck’s art, for example, is a text by an English scholar, Thomas Marshall, who gathered his own information directly from the painter when he stayed in England). Based on these documents, it is assumed that Van Dyck was critical of his colleagues who painted “alla prima,” that is, they applied color directly to the prepared medium rather than using drawing, or constructing the work through a series of layers. According to Antoon van Dyck, the method of “layering paint” was best, best done by making use of preparatory drawing, a lean tempera primer, and then applying gradually thicker and thicker layers of paint. In practice, Fasce observes, “the color spread in tempera was exploited as a pictorial sub-modeling, diversifying it in the different areas of the painting, on which the final oil layers were applied, based on an underlying drawing plan.”

The study of the paintings served to understand whether Van Dyck actually painted following this technique, and how his modus operandi developed. Non-invasive analyses (macro- and micro-photographs, infrared analysis, infrared trans-irradiation, false-color infrared) were first carried out, then samples of two paintings (the Portrait of Paolina Adorno Brignole Sale and the Portrait of Anton Giulio Brignole Sale) taken during a restoration dating back to 1996 were analyzed, and the results were compared with analyses carried out on some Van Dyck paintings preserved in foreign museums.

In Michela Fasce’s book, the treatment is divided into several chapters each devoted to a phase of the process: the choice of support, preparation and priming, preparatory drawing, and pictorial layers, with a concluding chapter summarizing Antoon van Dyck’s painting technique, and fact sheets on the sixteen works examined. Regarding the media, Van Dyck used to work on both panel and canvas, and it was noted that in at least one case, the Portrait of Ansaldo Pallavicino, the artist chose a canvas with a more sturdy and particularly suitable for achieving certain pictorial effects, which obviously suggests that the client spared no expense in having the painter portray him and thus induced him to choose a more valuable medium than those he usually used.

Antoon

Antoon Antoon

Antoon

The analysis of the works has made it possible to identify preparatory layers, spread according to the colors Van Dyck then intended to apply: for example, if he had to paint a painting with dark tones, he did not use a light imprimitura but spread a dark preparation using the tones of the preparation itself as a pictorial undermodeling to increase the depth of the color, and conversely for light tones this procedure was carried out with a gray preparation, found in several paintings. The paintings with the light-colored primer then allowed precise observation, where present, of the preparatory drawing, which was analyzed through infrared imaging investigation. On the drawings, Fasce’s study found a contradiction to what Thomas Marshall reported about Van Dyck’s technique: in fact, the painter claimed that the preparatory drawing had to be perfect in every detail, so that it would not have to be altered later. Instead, analysis revealed that theunderdrawing could often be modified. For the artist, in fact, “the constructive lines of the design,” Fasce writes, "are sketches useful for quickly setting up the idea of the painting. In some cases they are functional for constructing the contour lines of the architecture and faces in the pictorial realization. One could almost consider them ’design-pictorial drawings,’ consisting of a black line suitable both for setting up the drawing layout and for pictorially defining the figures." As for the methods by which the artist traced the drawing, in a couple of cases a single dry, charcoal tracing was found, in some cases a sketch made with brush and liquid medium , while in most cases the artist first drew dry and then reinforced the drawing with brush.

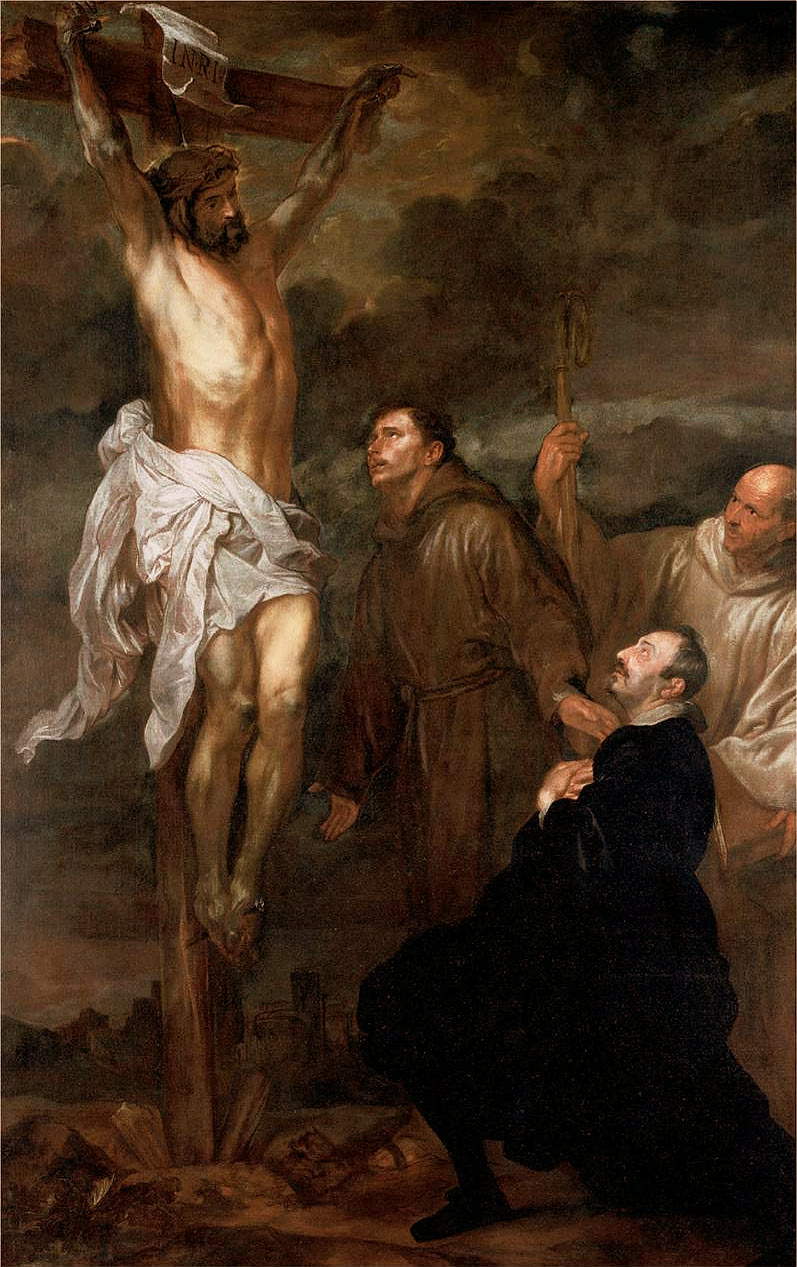

As for the paint layers, cases have been found where Van Dyck used pigments typical of the seventeenth-century palette: Enamel (or enamel) blue and indigo blue, for white the white lead or calcium carbonate, lead yellow, antimony yellow, yellow lacquer, various ochres, cinnabar, brown earths such as Cassel’s earth or Van Dyck brown (the latterlatter is an earth with a lot of organic material), and for greens the artist usually mixed blue with yellow, but copper green and copper resinates have also been found. Often the preparation color was left exposed with a “saving” technique, especially when it had reddish tones, which were useful in laying out the complexions. Antoon van Dyck was then used to apply opaque brushstrokes that served to conceal the texture of the support and the preparation, with a thick, opaque paint material with black outlines. In the fact sheets of the works analyzed (including the aforementioned Portrait of Ansaldo Pallavicino, the Crucifixion of San Michele di Pagana, the Spirant Christ of the Royal Palace, the Portrait of Geronima Brignole Sale with her daughter Maria Aurelia, the Christ of the Coin of the Red Palace, and the Portrait of Paolina Adorno), the account of the analysis, images of the work, and those of the scientific examinations are provided.

The analysis showed that, in Genoa, Van Dyck did not significantly change his technique: the changes were mainly in the preparation. For the drawing, for example, the artist for his entire career would use the same procedure found in the Genoese paintings (making, in rare cases, small variations): the artist had learned it from Rubens, although compared to the master Van Dyck modified, precisely, the way of preparing the painting, elaborating new solutions precisely in correspondence with his stay in Genoa. “The first Antwerp period,” Fasce explains, "is characterized by a single preparatory layer of gray color and, when there are two layers, the one underneath the paint film, that is, the imprimitura, is always of a gray hue, apart from one case in which it is brown. As it travels the peninsula, the preparation diversifies, taking on brownish-gray and beige tones if there is only one layer, while, if there is also the imprimitura, which may be gray or pink or yellow, the grounds vary from reddish brown to light brown and beige. This technique of constructing the lower layers is also found in the second Antwerp sojourn, with the difference that the pink or yellow tones of the imprimitura are no longer present." A peculiar picture thus emerges: Van Dyck was practically insensitive to Italian artistic techniques, and continued to work according to the knowledge he had gained in Antwerp. However, he had to modify his preparation because of the media available in Genoa, which required special techniques. Fasce’s study, in addition to ascertaining these aspects, can now provide a starting point for those who would like to understand whether his followers and friends who worked in Italy (e.g. Jan Roos or other artists who were inspired by Van Dyck) adopted the great Flemish artist’s procedures, or whether they were instead more permeable to local operations.

|

| How did Van Dyck paint in Genoa? Michela Fasce's book explains. |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.