It is well known that several art historians manifest some difficulty when called upon to change their register in order to meet with favor and to arouse the interest of the general public. This is not the case for Eugenio Riccomini (Nuoro, 1936), one of the great masters of Italian art history: a pupil of Carlo Volpe and Stefano Bottari as well as a friend of Francesco Arcangeli, Riccomini has always been able to combine his career as a distinguished art historian, an official in the Superintendence and author of important studies on Emilian painting of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, with a rich and appreciated activity as a popularizer. The latest chapter in this “second face” of Eugenio Riccomini is a book published this year by Pendragon: it is entitled L’altro Ottocento. Russia, Germany, Austria and it is an agile and fresh account that, between the meshes of the great art history of the nineteenth century inCentral Europe (the one traced by personalities such as Friedrich, Klimt, Repin), also brings to the reader’s attention a less known nineteenth century (an “other” nineteenth century, precisely) but not for this reason less surprising, less dense in meaning, less politically important, even less exciting, if you will.

With a dry, discursive, captivating, at times uncoveredly ironic style (characteristic of Riccomini), the author takes the reader on a journey from Moscow to Munich, from Vienna to even Rome (where the vicissitudes of several of the artists Riccomini discusses were intertwined) to discover, in an eminently diachronic perspective, the most significant (but also the most forgotten) personalities of the Russian, German and Austrian nineteenth century, without losing sight of the historical context, which, indeed, serves as an introduction to each of the three chapters of which The Other Nineteenth Century is composed. What emerges is a great choral narrative, certainly not exhaustive or even complete (that would be impossible in just one hundred and twenty-five pages), but nonetheless capable of providing the reader with at least the coordinates to orient himself in the historical period of reference and to appreciate, alongside the names of the best-known artists, those of great personalities such as Ivan Konstantinovič Ajvazovsky, outstanding master of Russian Romanticism, Karl Blechen, a kind of German “alter ego” of Turner, Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller, an extraordinary Austrian portraitist of the first half of the 19th century.

Underlying the book is the idea that the nineteenth century is identified primarily with French painting: undeniable certainly is the capital contribution that painters such as Courbet and Monet made to the history of art, yet Riccomini feels almost a sense of unease that in the common perception (and until not long ago also in university classrooms) the nineteenth century of Russia, Germany and Austria does not occupy the position it is due. “In the course of several years of classical studies,” the author explains, “following high school, and then, thank goodness, university lectures in art history, I never heard names, now well known, such as those of Turner, Friedrich, and others who were not French, pronounced in the classroom; and let alone ever hearing, or seeing anything, of Russian, or Slavic, and even German painters. There is, therefore, even today an ’other’ nineteenth century. And that is, little or very little known; and indeed completely unknown, and unexpected.”

|

| Eugenio Riccomini, The Other Nineteenth Century. Russia, Germany, Austria |

What Riccomini calls, on several occasions, a “walk” through the works of the nineteenth century, takes its point of departure from a Russia divided between Slavophiles and zapadniki, the pro-Westerners (literally the “Occidentalists”): on the one hand, those who admired Western Europe while blaming it and, on the contrary, exalting Russia’s intellectual, social, philosophical, religious and political heritage, and on the other hand, those who pushed for an opening to the outside world. A diversity of orientations that, Riccomini specifies, “can be read very well in Russian painting,” so little known perhaps also because it is so deeply rooted in the context of its country of origin. For artists who longed for an opening to the West, Italy often constituted “a landing place, a dream, an escape route.” this was the case for Sil’vestr Feodosievič Ščedrin (St. Petersburg, 1791 - Sorrento, 1830), who settled permanently in our country, enamored as he was of its landscapes and ruins that became the protagonists of his paintings, or for one of the most significant painters of the early Russian 19th century, Karl Pavlovič Brjullov (St. Petersburg, 1799 - Manziana, 1852), who was animated by a strong archaeological passion and the author of an extraordinary painting dedicated to the tragedy of Pompeii, the drama of which was aroused precisely by his constant visits to the ruins of the Campanian city. Artists who, on the contrary, were almost totally devoted to a painting eager to depict contemporary Russia include such personalities as Il’ja Efimovič Repin (Čuguev, 1844 - Repino, 1930), whose Battlers of the Volga, with their perceptible suffering, remain one of the most famous images of the Russian nineteenth century, or such as Vasilij Ivanovič Surikov (Krasonjarsk, 1848 - Moscow, 1916), an artist who proposed a painting “oblivious of all classicism” that, Riccomini suggests, in its focus on episodes of Russian history seems almost to pursue a didactic intent.

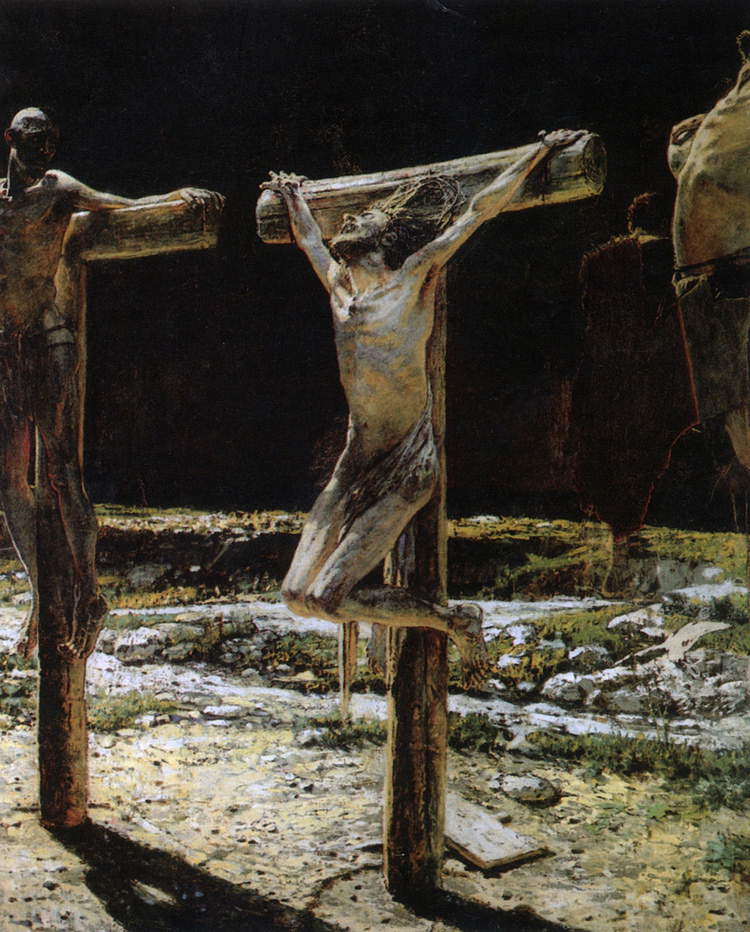

Alongside these figures are those of innovators such as Ivan Kostantinovič Ajvazovskij (Feodosiya, 1817 - 1900) who traveled extensively through Europe (also forging a fruitful friendship with William Turner) bringing the instances of Romanticism to his homeland (his Ninth Wave can rightly be included in the list of the most pregnant masterpieces of European Romanticism), such as Nikolaj Nikolaevič Ge (Voronež, 1831 - Ivanovsky Chutor, 1894), a deeply anti-academic artist capable of highly dramatic and shocking scenes (this is the case with his Crucifixion of 1892), or such as Michail Aleksandrovič Vrubel ’ (Omsk, 1856 - St. Petersburg, 1910), perhaps the first to open up to the avant-garde (he also looked to a very young Picasso, in the Paris of 1906), before the great season, inaugurated by Kandinsky, during which Russian art (with artists such as Malevič, Gončarova, Tatlin) would take on European significance.

|

| Karl Bryullov, The Last Day of Pompeii (1833; oil on canvas, 456.5 x 651 cm; St. Petersburg, Russian Museum) |

|

| Il’ja Repin, The Volga Boatmen (1870-1873; oil on canvas, 131.5 x 281 cm; St. Petersburg, Russian Museum) |

|

| Ivan Ajvazovsky, The Ninth Wave (1850; oil on canvas, 221 x 332 cm; St. Petersburg, Russian Museum) |

|

| Nikolai Ge, Crucifixion (1892; oil on canvas, 278 x 223 cm; Paris, Musée d’Orsay) |

As for the trip to Germany, Riccomini has it begin immediately after the end of the Napoleonic age, when revolutionary impulses were thought to have died down, and instead one necessarily had to come to terms with a German area in which “ideas of freedom, equality and even fraternity” were fermenting, embodied by intellectuals who cultivated “love for the arts, culture, and thought.” At the same time, however, Germany, though politically divided, remained a land united by language, literature, philosophy, music, and a thriving economy. Not by religion: in this sense, north and south were distant realities, with a north in which the Protestant Reformation had spread and which was therefore more austere than a Catholic south where a “romantic love of ancient beauty” was “widespread,” which would also lead German painters to be seduced by the wonders of Mediterranean Europe. Among them was Philipp Otto Runge (Wolgast, 1777 - Hamburg, 1810), who was fascinated by classical culture and driven by the purpose of seeking the Gesamtkunstwerk, the total work of art, in a combination of painting, sculpture, architecture and music (and in his own way he would succeed). The relationship with classical culture of a master of European stature such as Caspar David Friedrich (Greifswald, 1774 Dresden, 1840) is well underscored by the fact that the artist never traveled to Italy, aware that if he had visited our country (where he never went), he would have considered returning to Germany stifling. Thus, those sublime atmospheres of his, where “one can almost feel the breath of an omnipotent and almost threatening divinity,” to use Riccomini’s words, where there is an infinite, majestic and disturbing nature, where man feels tiny in the face of what surrounds him, also make their entrance in the only painting in which Friedrich depicts a classical monument, namely the temple of Juno in Agrigento (known through an illustration): the warm glow of Sicily is totally obliterated and instead an icy, almost oppressive light is introduced, giving an unprecedented aura of poetry to the ancient classical remains.

The relations between Germany and Italy are even made explicit by Friedrich Overbeck (Lübeck, 1789 - Rome, 1869) in his celebrated Italy and Germany of 1828, and entered into the art of many Germans influenced by the paintings of the great artists of the Italian Renaissance (Overbeck himself was among the painters who were subjected to this fascination), or even, simply, by the inhabitants of the lands south of the Alps: when he painted his Paolo and Francesca, Anselm Feuerbach (Spira, 1829 - Venice, 1880) had for a model a woman from Ciociaria, Anna Risi, who gladly lent herself to become part of Feuerbach’s “solemn classicism.” German painting, however, could also be terribly crude: this is demonstrated by, among others, Adolf von Menzel (Breslau, 1815 - Berlin, 1905), an artist of extraordinary talent (“the most skilled painter, I believe, of the German nineteenth century,” Riccomini points out), who on the Forge of 1875 poured out, by simply painting the interior of a factory, the anguish of industrial society (the composition is dark and enlivened only by the glow of molten metal, it is crowded, it is asphyxiating). And this is demonstrated by the artists who, like Menzel, took the path of realism: the social denunciation that emerges from the paintings of Max Liebermann (Berlin, 1847 - 1935) was even invisible to the Nazis, who declared it Entartete Kunst, when Liebermann, old and tired, had already passed the threshold of eighty years of age and had to end his existence suffering such humiliation.

|

| Caspar David Friedrich, The Temple of Juno at Agrigento (1830; oil on canvas, 54 x 72 cm; Dortmund, Museum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte) |

|

| Friedrich Overbeck, Italy and Germany (1828; oil on canvas, 94.4 x 104.7 cm; Munich, Neue Pinakothek) |

|

| Anselm Feuerbach, Paolo and Francesca (1863-1864; oil on canvas, 137 x 99.5 cm; Munich, Schackgalerie) |

|

| Adolph von Menzel, The Forge (1872-1875; oil on canvas, 158 x 254 cm; Berlin, Staatliche Mueeen) |

Eugenio Riccomini’s “walk” ends inHabsburg Austria, whose capital, Vienna, was among the most culturally vibrant and active cities in Europe at the time: the author points out how, in the Austrian capital, the first great international school of art history (the School of Vienna, precisely) had been born, without neglecting urban renewal, Freud’s psychoanalysis, musical and political culture (it was an Austrian, Leopold of Habsburg-Lorraine, later Leopold II of Tuscany, who first abolished the death penalty, and this happened in the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, which he ruled, in 1786). Riccomini identifies the “thirst for novelty” as the main characteristic of Austrian painting of the time: the Vienna Sezession, the so-called “Secession” that gave rise to a real break of European resonance with what had come before, was one of the highest moments in the history of Western art and fully embodies this will, on the part of the young Austrian painters of the second half of the 19th century, to break with tradition (a will that was also manifested in Germany with the Secessions of Munich and Berlin: this is discussed in the chapter devoted to German painting). But even before the Secession there was no shortage of good artists, albeit less well known: among them, Riccomini cites the singular case of Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller (Vienna, 1793 - Hinterbrühl, 1865), an excellent portrait painter who, however, had difficulty establishing himself on the high-end market, and was therefore forced to paint marvelous still lif es (a genre more accessible and more easily sold than the portrait) in order to support himself. And exceptional portrait painter was also Hans Makart (Salzburg, 1840 - Vienna, 1884), a decidedly versatile painter, as comfortable with portraiture (note the marvelous one of Dora Fournier-Gabillon) as with history painting, mythological painting, and allegorical scenes. Realist instances, on the other hand, were carried forward by Mihály Munkácsy (pseudonym of Mihály Lieb, Munkács, 1844 Endenich, 1900), a Hungarian painter whose art gave substance to the harsh reality of the working-class world.

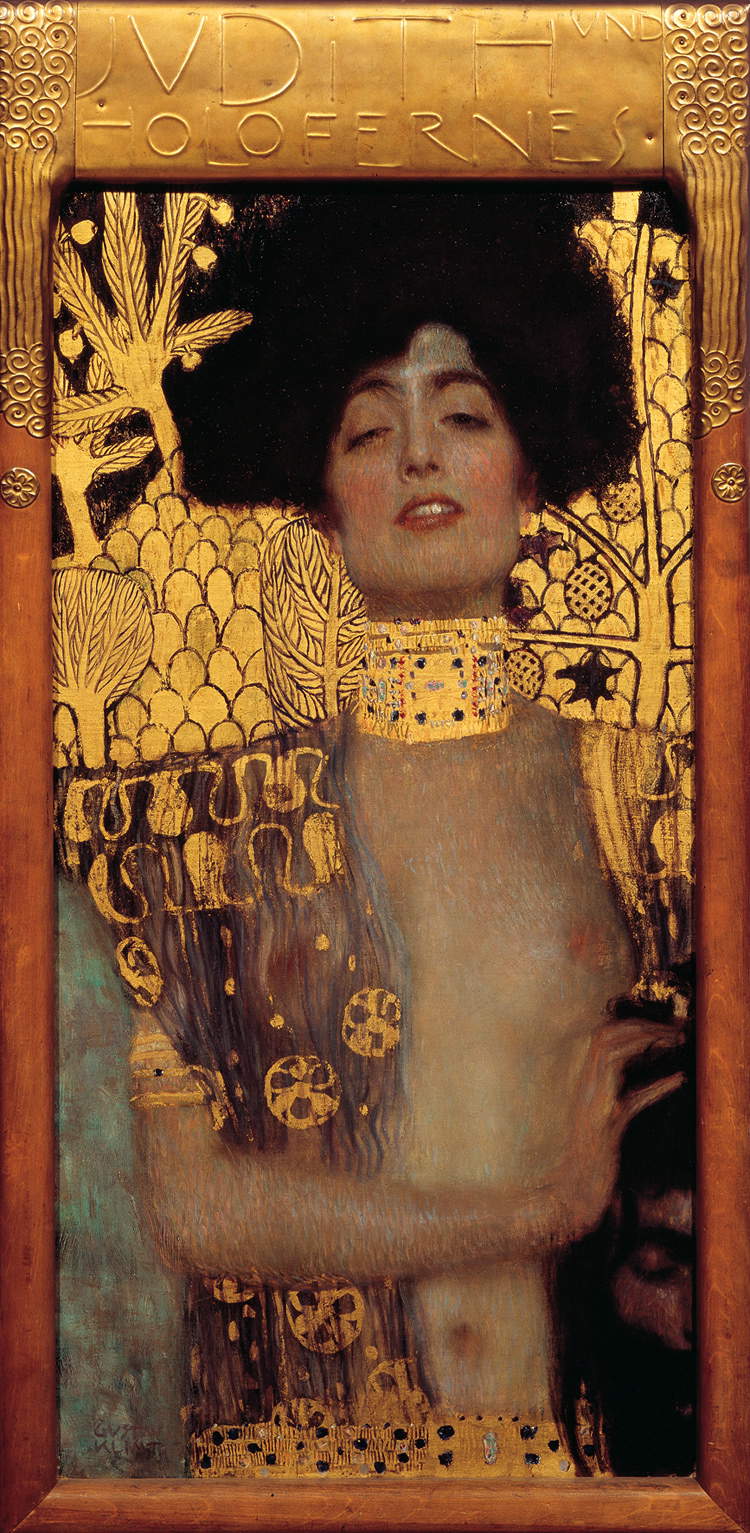

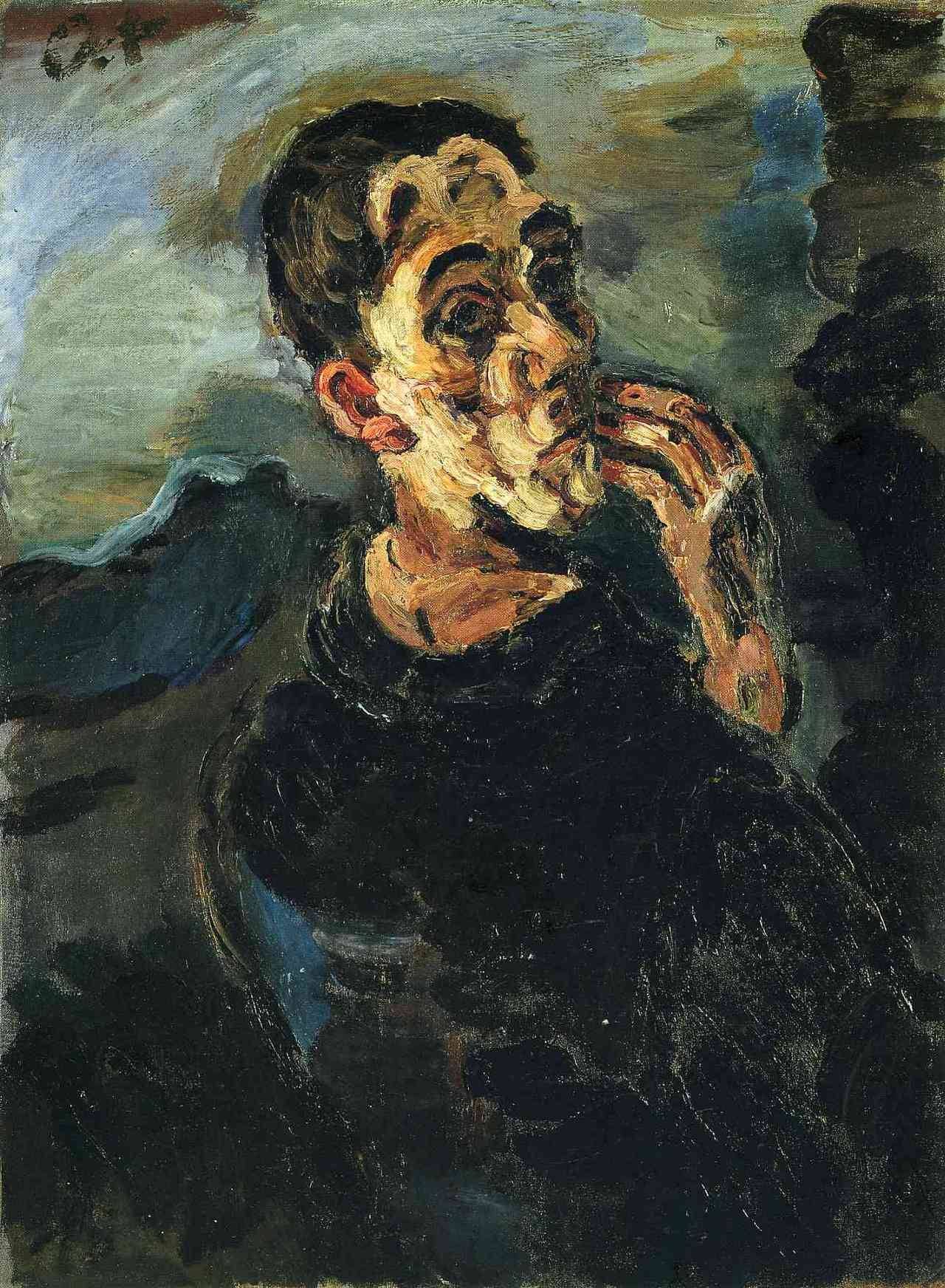

The extensive chapter devoted to the Vienna Secession opens with the observation that “secession means entry into the modern age”: this is because the Secession artists were strongly fascinated by the achievements of contemporary society, and they wished to develop a language that could be adapted to that modernity. Each of the Secession artists responded to this need in his or her own way. Gustav Klimt (Baumgarten, 1862 Vienna, 1918) with his extraordinarily refined painting, which mixed classical memories (Klimt’s career, after all, began under the sign of the purest Academy), Byzantine elements (the painter had been to Ravenna and was well acquainted with its mosaics), and figures reminiscent of coeval Symbolist painting. Particularly illustrative is the Judith, a sort of “unusual assemblage,” writes Riccomini, “of parts treated in the naturalistic style, which Klimt mastered in an exemplary way, and of splendid decorative parties, even gilded, as if it were the background of a Byzantine mosaic.” Of a different sign was the nervous, disturbing and violent painting of Egon Schiele (Tulln an der Donau, 1890 - Vienna, 1918), whose works aroused almost disgust at the time (Riccomini cites, among others, the Portrait of Trude Engel, which was vehemently rejected by the addressee), and the same is true of the art of Oskar Kokoschka (Pöchlarn, 1886 Montreux, 1980), an equally “aggressive and fierce” painter especially in his youth (as the author of The Other Nineteenth Century defines him: a work like Self-Portrait with Hand to Mouth unequivocally sanctions the assumption that beauty andart can travel on two separate tracks without ever meeting.

|

| Hans Makart, Portrait of Dora Fournier Gabillon (1879-1880; oil on canvas, 145.5 x 93 cm; Vienna, Museen der Stadt) |

|

| Gustav Klimt, Judith I (1901; oil on canvas, 84 x 42 cm; Vienna, �?sterreichische Galerie Belvedere) |

|

| Egon Schiele, Portrait of Trude Engel (1911; oil on canvas, 100 x 100 cm; Linz, Neue Galerie der Stadt) |

|

| Oskar Kokoschka, Self-Portrait with Hand to Mouth (1918-1919; oil on canvas, 83.6 x 62.8 cm; Private Collection) |

The Other Nineteenth Century succeeds admirably in the task of broadening our views of nineteenth-century art, and it does so with a kind of quick vademecum (this is the flavor of the book) that nonetheless manages at the same time to map out the rich nineteenth-century art events of the three countries surveyed, ensuring a dense, yet quick and snappy summary: It will be up to the reader to draw insights into the artists Riccomini probes from a bird’s-eye view but without ever losing punctuality in profiling them. In essence, The Other Nineteenth Century is a good popular product: it establishes a friendly atmosphere with the reader, it succeeds in intriguing him or her by keeping him or her glued to the pages from first to last, it does not skip any passage, it uses an accessible and almost friendly register, and it touches precisely on all the artists presented. And the book is also, let it be said, a demonstration of how Eugenio Riccomini has not yet finished surprising us.

Eugenio Riccomini

The Other Nineteenth Century. Russia, Germany, Austria

Pendragon, 2018

125 pages

14 euros

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.