From baroque to glory, seventeenth-century Milanese sculpture in a volume by Susanna Zanuso

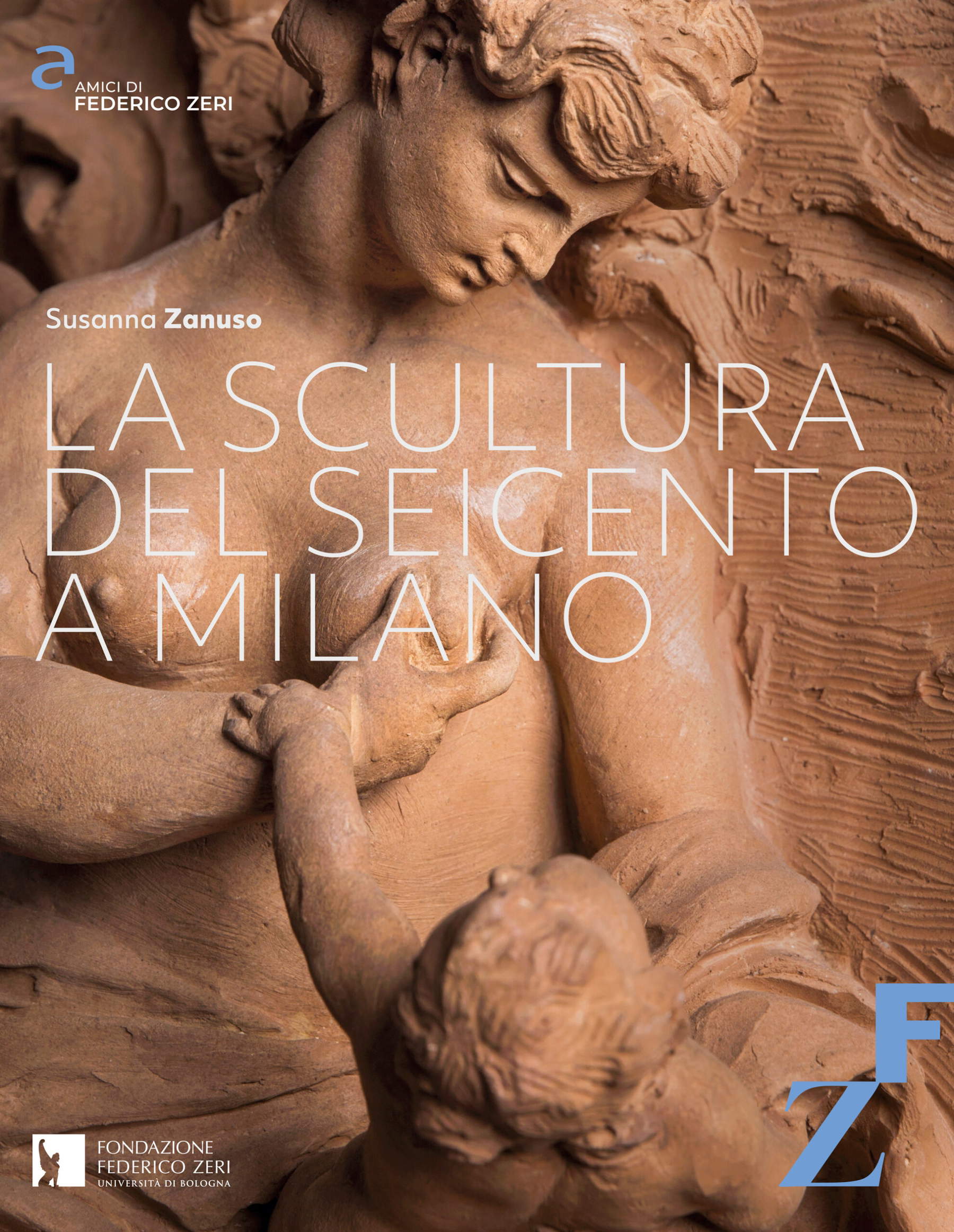

Milan, 17th century. In a period of great cultural and artistic ferment but also strongly marked by the political and social vicissitudes of the time, the capital of the Duchy, at that time under the rule of the Spanish monarchy, stood out within the Italian artistic scene for its refined and peculiar sculptural production. And it is precisely seventeenth-century Milanese sculpture that is the subject of an in-depth book, recently published, by art historian Susanna Zanuso, who has been studying this subject for years: It is titled La scultura del Seicento a Milano (412 pages, 60 euros, ISBN 9788894489231) and is intended to be, as Walter Padovani, president of the Associazione Amici di Federico Zeri that published it, a “tool for in-depth study with a rich repertoire of known and especially lesser-known, when not unpublished, works, flanked by some 20 biographies of even unknown artists.” The book has a very simple structure: an introductory essay followed by several monographic chapters devoted to the sculpture personalities who worked in seventeenth-century Milan.

Lombard works of the seventeenth century, Zanuso reminds us right in his opening essay, are characterized by two main factors: a marked adherence to the traditions of the territory and a tendency toward stylistic closure to outside influences. Formal independence is not considered a limitation for seventeenth-century Milan; rather, it is asserted as the core of its creative force, a power capable of developing an incomparable language while remaining in dialogue with the artistic centers of the time. Although criticized by scholars such as Rudolf Wittkower, Milan’s stylistic closure allowed the development of an entirely autonomous artistic language.

The importance of the Milan Cathedral building site

A panorama that can be traced back to the construction of Milan Cathedral and its sculptural decorations, a complex architectural activity. The result presents itself as an unmissable opportunity for the training and affirmation of a generation of local sculptors. Organized in a school refounded in 1612 thanks to the legacy of the nobleman and politician Guido Mazenta, the masters and students of the Duomo site collaborated together in a system with technical rigor adhering to the devotional and commemorative needs of the time.

But for what exactly does the sculpture of the Milanese school stand out? Undoubtedly, according to Zanuso, by immediacy in expression, a calcified dramatic quality, as well as a strong rootedness in the spiritual needs of the period. These are all characteristics evident in works such as the sculptural group Cain and Abel by Dionigi Bussola (1615 - Milan, 1687), created between 1663 and 1672 for the exterior of the Duomo, an emblem of the city’s cultural identity. Although the propensity for Milanese artistic self-sufficiency, there was no shortage of openings to the outside world. Episodes such as the attempt in 1644 to involve artists such as Andrea Bolgi known as the Carrarino (Carrara, 1606 - Naples, 1656), a collaborator of Gian Lorenzo Bernini (Naples, 1598 - Rome, 1680), Bussola or Carlo Antonio Bono, testify to Milan’s interest in engaging with the main artistic centers of the time. Bolgi, for example, author of the St. Helena, one of the four statues placed in the pylons of the dome of St. Peter’s and made between 1629 and 1639, was known for his ability to translate the principles of Bernini’s Baroque art into a wholly personal language with great emotional impact. The city’s purpose thus reflected the Milanese patrons’ desire to update the local art scene, bringing it in tune with the stylistic innovations coming from Rome, then the epicenter of European Baroque. Nevertheless, outside influences never compromised the identity of the Milanese school, which while maintaining its own distinctive character was able to assimilate new elements and make them its own. The cathedral building site thus emerged as the flourishing emblem of a singular and innovative artistic tradition that found form in the defining material of Candoglia marble.

Precious, majestic, refined, and characterized by shades ranging from white to pink, the marble was the right choice for the basilica’s cladding. The motivation? The decision lies in the desire to resolutely convey a visual power capable of engaging the faithful, while accepting some limitations to the precision of execution compared to more malleable materials. The choice of Candoglia marble is also combined with an apotropaic vision and valence of the sculptural works that have contributed to mystery and magnificence. And when we speak of “apotropaic valence,” we refer to an intention that attributes to an object, image or action the ability to ward off evil or negative influences. Here, the works of the Cathedral have this function.

Many of the designs, such as the vaults of the chapels or the feat of the adoring Angels placed in the niches of the pillars facing the choir, included sculptures placed at a height unreachable to the human eye. In fact, more than the detail of the individual works, the grandeur of the entire complex was striking for the sheer number of works present. As early as the end of the seventeenth century, in fact, Carlo Torre, a great connoisseur of the painting of his time, catalogued “four thousand and four hundred statues, and in the interior and exterior parts,” a count that highlighted the grandeur of the cathedral.

The artists of the early 17th century: from the last links with Mannerism to the Baroque

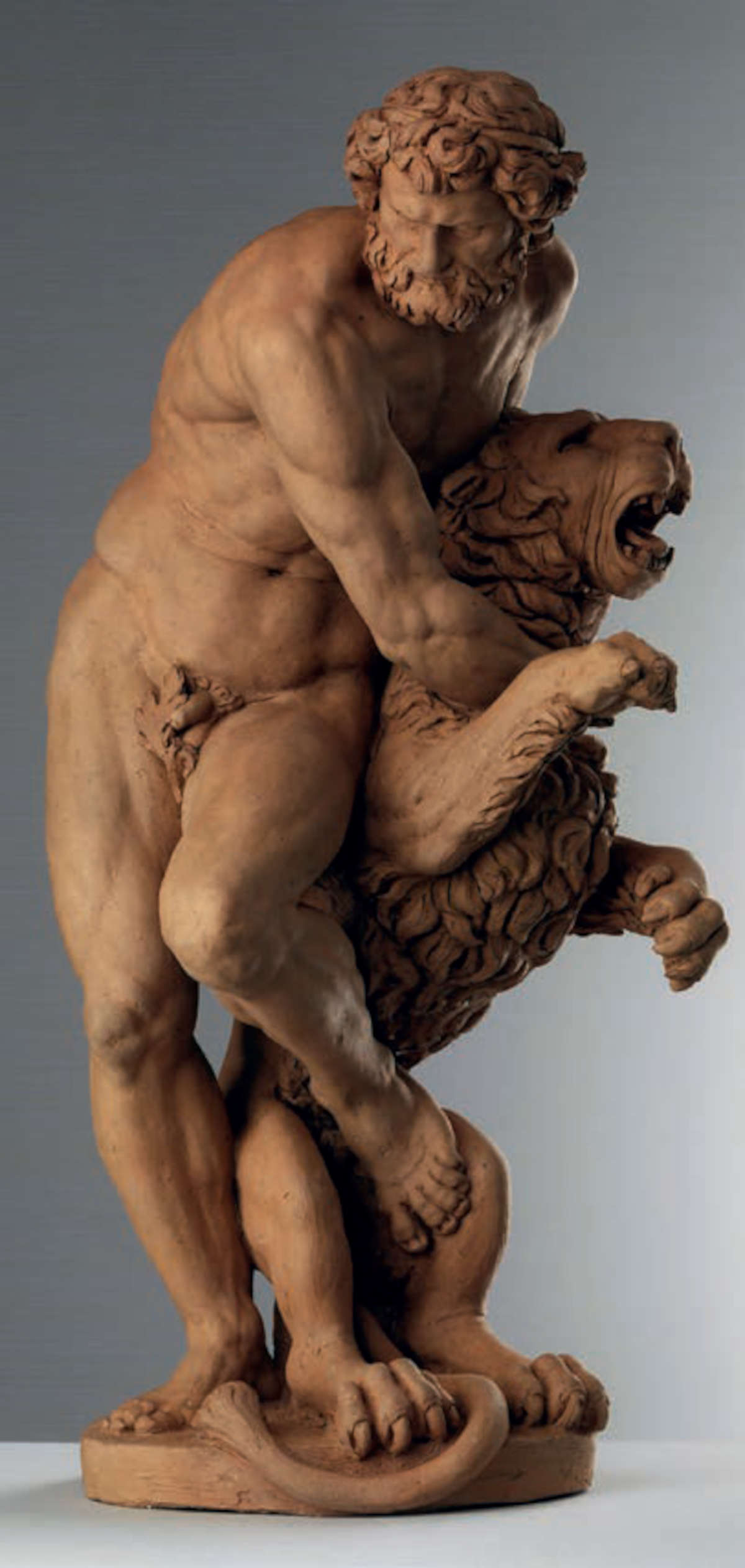

Among the most significant works on the site we can certainly highlight the reliefs of the Stories of the Virgin in the Duomo’s tornacoro, started in the early 17th century by Gianandrea Biffi (1580/1581 - Milan, 1630/1631) and Marco Antonio Prestinari (Claino, 1570 - Milan, 1621). Biffi, heir to Francesco Brambilla the Younger, whose pupil he was, assumed the role of master in the Duomo upon his death in 1599. Particularly skilled in creating models in plastic materials such as wax and terracotta, Gianandrea Biffi shaped sketches destined to be molded into marble or bronze by other artisans, including sculptors, goldsmiths and foundrymen. Marco Antonio Prestinari, on the other hand, with a broader education, had important relationships with the court of Parma and Piacenza between 1600 and 1602. All this allowed him to broaden his artistic knowledge. His production, initially characterized by a Mannerist vein, is evident in works such as the Michelangelo-esque Telamons of the Saronno sanctuary and theHercules with the Nemean Lion (recently rediscovered). As the years went by, his style moved toward a more decorous, cultured and measured classicism in keeping with the artistic ideals of Cardinal Federico Borromeo (Milan, 1564 - 1631), who considered him the best sculptor of his time.

A major contribution to the site was also made by sculptor and painter Giovanni Bellandi, close to the Genoese artistic milieu, whose style differed in its independent and progressive approach. In reliefs such as the Wedding at Cana of 1620, Bellandi analyzed stylistic solutions that could transform marble into an almost pictorial discipline, drawing inspiration from the artistic expressions of painters and sculptors Giovanni Battista Crespi known as Cerano (Romagnano Sesia, 1573 - Milan, 1632) and Giulio Cesare Procaccini (Bologna, 1574 - Milan, 1625). Bellandi had already worked at prestigious sites such as Sant’Alessandro and the Certosa di Pavia, both dominated in the first half of the century by the presence of sculptors from Genoa: despite this, his style, so independent, did not actually find further development. Now, in addition to Giovanni Bellandi, Gianandrea Biffi and Marco Antonio Prestinari, figures such as Giovan Pietro Lasagna and Giovanni Battista Maestri, known as the Volpino, were present within the panorama of seventeenth-century Milanese sculpture.

In the transition marking the decline of late Mannerism and the rise of the Roman Baroque, artists such as Gaspare Vismara (Milan, 1588 - Arese, 1703) and Lasagna, both of whom survived the plague of 1630 and were active until the early 1950s, also emerged. The two sculptors were called upon to create works inspired by Cerano’s designs, including sculptures for the facade of San Paolo Converso and reliefs for the Duomo. In particular, in 1631 Vismara tried to assert his art with the Carola d’angeli destined for the main door of the Cathedral, a work that he himself described as among the most challenging and grandiose ever made. In reality, the result did not fully meet expectations. Of Vismara’s work there are references to works studied and created for private collections, including a Cupid that was part of the Castellazzo Gallery of collector Galeazzo Arconati.

The protagonists of the central decades of the seventeenth century in Milan

The production of small works, an aspect considered secondary in the Milanese artistic tradition, represented a fertile ground for experimentation for many local artists. Certainly a field neglected by historical studies, it currently reveals itself as a key to understanding theevolution of Milanese sculpture between the 17th and 18th centuries. In any case, Giovan Pietro Lasagna protagonist of seventeenth-century Milan turns out to be among the most interesting sculptors of the period. Among the best-known works is the marble group of Venus and Adonis, also recently rediscovered, which confirms the artist’s ability to blend different styles and influences. Indeed, in his work one can perceive a comparison between the Mannerism of Francesco Prestinari, characterized by a complex formal tension, and the pictorial and narrative fluidity of Cerano. A central element in Lasagna’s activity also emerges from the documents that, between 1642 and 1643, record several fees for the creation of equestrian statuettes for the Trivulzio family. Although the bronze statuettes have not been identified, they do indeed suggest that Lasagna was a creator of small-scale decorative artifacts, as well as a master of monumental works.

In 1645, two additional figures became involved in the work on the Duomo: Dionigi Bussola, who had just returned from a period of study and work in Rome, and Carlo Antonio Bono, his collaborator and friend. Bono had studied with Francesco Mochi (Montevarchi, 1580 - Rome, 1654), among the initiators of the Italian Baroque, known both for his energetic approach and for his attention to anatomical detail, an aspect evident in his work Annunciation of 1603. Mochi’s influence was felt by Bono and other Milanese artists such as Procaccini and Bellandi, mentioned earlier. With Bussola becoming protostatuario, then director of works on the cathedral in 1658, a new generation of sculptors emerged.

The artists, while adopting the decorative canons of the Roman Baroque that included the use of putti and elaborate drapery, also developed a decidedly more intimate and modest narrative language, in contrast to the solemn re-enactments typical of Rome. An example? Bussola’s Allegories of the Sciences made between 1670 and 1673 demonstrate this. Through the different symbolic attributes and gestures that reveal the various personalities, the female figures in the Allegories embody the different scientific disciplines. The same narrative is also evident in the chapels of the Sacred Mounts, where Bussola represented various biblical episodes scenographically and with engaging theatricality. Alongside the artist also stood Giovanni Battista Maestri, known as the Volpino, his collaborator. Unlike Bussola’s works, Volpino’s works are characterized by a more intimate and meditative artistic vision. Despite a short career, Volpino was an important figure in Milanese sculpture, as indeed is evidenced by the authoritative commissions he received and finds, including an allegorical female portrait to this day preserved in Spain.

Toward the 18th century

Another protagonist of the Milan period was Carlo Simonetta, Bussola’s son-in-law and active in the 1780s. Among his best-known works are the decorations of the Chapel of the Crucifix in the church of Santa Maria alla Porta, where Simonetta demonstrated an innate skill in the use of light and shadow to create the dramatic effects characteristic of the Baroque. His influence also spread to his pupils, including Stefano Sampietro and Francesco Moderati, who carried on the Milanese tradition in the city’s Roman sites. In addition, fundamental was the contribution of artists such as Giuseppe Rusnati (Gallarate, 1650 - Milan, 1713) and Camillo Rusconi (Milan, 1658 - Rome, 1728), who completed Milan’s sculptural scene by bringing the direct creative style of the Roman school. Both gave within the city an artistic language that combined the striking features of the Baroque with the peculiarities of the capital of the Duchy. Giuseppe Rusnati was initially trained in Milan but developed his artistic language thanks to a stay in Rome that allowed him to study the works of Bernini and Algardi closely. Among Rusnati’s most representative works are the Madonna and Child kept in the church of Sant’Antonio Abate in Milan and the decorations for the side chapels of the Duomo, where the artist managed to combine monumentality and intimacy.

The result? An example of the balance between Lombard tradition and Baroque innovation. Camillo Rusconi, on the other hand, was among the leading exponents of Milanese sculpture in the late 17th and early decades of the 18th century. Born in Milan, he moved to Rome to complete his training, where he came into contact with the most influential artistic circles of the time. On Roman soil he distinguished himself for the technical quality of his works such as the St . Andrew in St. John Lateran and for his ability to create images endowed with dramatic power. Back in Milan he played a fundamental role in transforming sacred sculpture. Indeed, he introduced a new, different approach characterized by a skillful use of light and a sensitivity to spatial composition.

Thus, from the analysis of seventeenth-century sculpture that developed from the capital of the Duchy and that Susanna Zanuso leads through the essay and then through the chapters on individual artists, a diverse panorama emerges, populated by artists characterized by highly individual expressions. Today, with more attention paid to the Milanese sculptors of the seventeenth century, Wittkower himself could in fact recognize that their value lies in having developed singular formulas, experimental and at other times ahead of their time, guided nonetheless by an autonomous and original perspective capable of producing results relevant to the Milanese scenario.

|

| From baroque to glory, seventeenth-century Milanese sculpture in a volume by Susanna Zanuso |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.