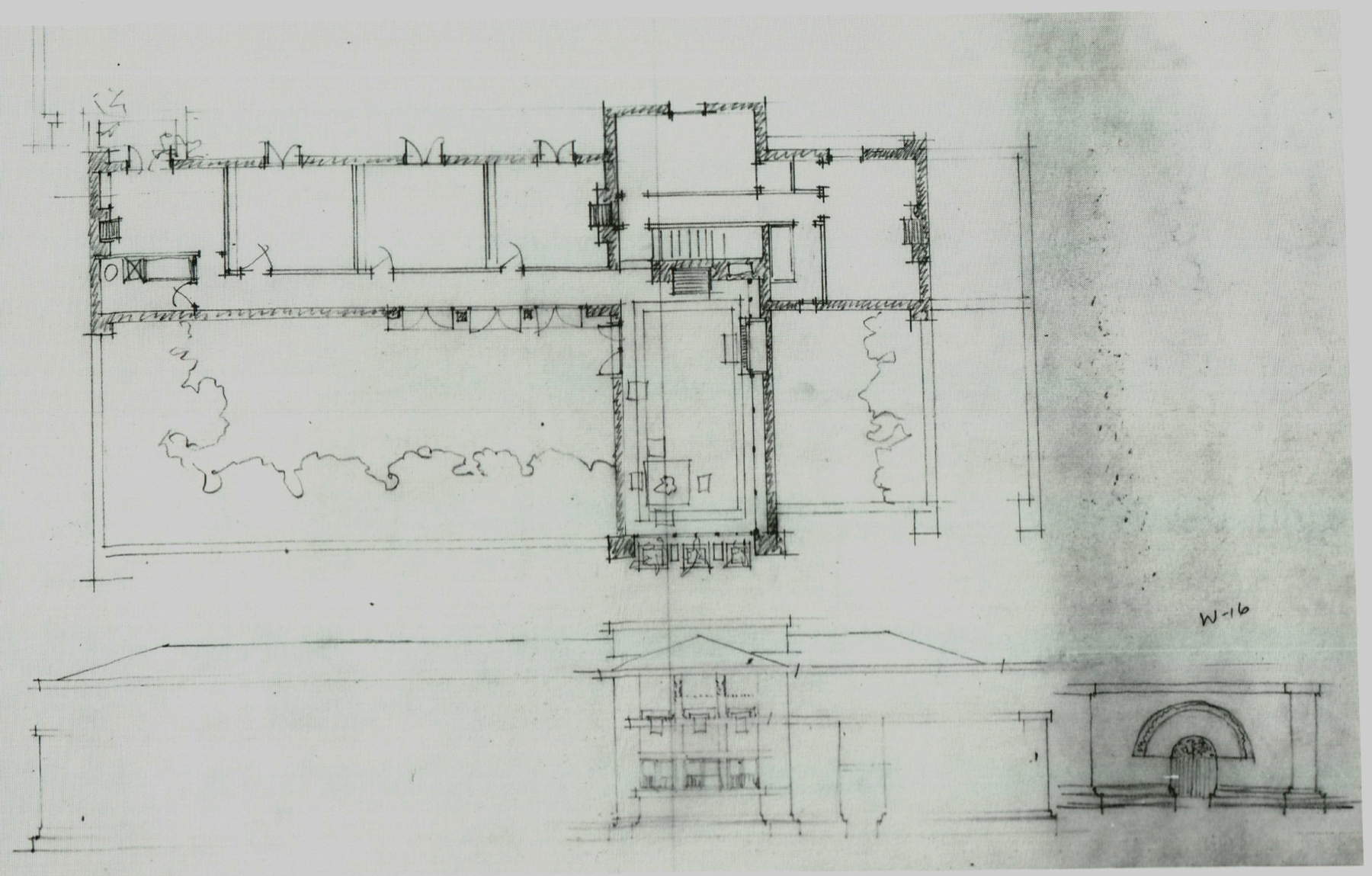

He considered architecture to be America’s “blind spot.” That dot that moves across the retina and becomes a disturbance that prevented his countrymen from seeing well how important architecture could be in the development of democratic society. For Frank Lloyd Wright, this was the woodworm that was to drive the 20th century man (but if he were alive he would say the same to the American of today) to understand the laws that govern his collective life and the way of inhabiting the earth by taking them from the natural order. Even today, his prophecy of an “organic” architecture, that is, one designed on the symbiosis between human space and nature, does not seem to be well understood by our societies, which also spend considerable capital and energy on ecology and environmental protection. Organic architecture is not a form of environmentalism or romanticism; in its form it is something analogous to the anthropometry on which the Greeks and other cultures based their art of building. Wright, too, adopts a metaphor related to the structure of the human body, and in an attempt to explain what he means when he speaks of natural pattern, he states that "it is the bone structure that is made according to the pattern of the face. The face is not the result of the bone structure, it is the structure that comes from the pattern of the face. In this way the structure can form a pattern. Pattern is the idea of form, and it is so in nature as in architecture.“ This phytomorphism that communicates the laws of nature to architectural structure causes The Illinois, the mile-high skyscraper, to take the structural form of a tree. But Wright thinks of it as a kind of ”total ornament,“ because nature itself ”continually builds patterns." Once again Wright challenges the academic distinction that had dominated in the nineteenth century between architects and engineers, where the former are delegated to the decorative exterior, while the latter to the technological component (where it is implied that engineers deal with the basics, while the architect is a kind of wallpaper designer). But it must be clear, Wright notes precisely, that it is not the pattern of a building, its framework, that determines the face, but it is the structure that derives from the pattern of the face. There is no longer any real distinction between form and content, and this is the most anticlassical view imaginable at the time.

Dictatorship of machines, congestion of cities, conceptual backwardness that considers building still from nineteenth-century patterns that think the exterior, the facades, before having organized the interior space by responding to the needs of those who have to live there: the bigness that has furore and connoted the urban landscape of this long beginning of the twenty-first century has been just that. A culture of the outsized container that has crushed with its gigantism all critical thinking by the common man, in a sense violating the correspondence Wright posited between architecture and democracy. The change of gaze consists in abandoning the idea of the box filled with so many useless things that separate us from our relationship with the landscape, with the discovery of a fluid space where there is no longer a separation between inside and outside and everything flows freely realizing a new order of beauty. This is possible, Wright argued, because iron and glass allow us to overcome the limitation of the wall that prevents that vital communication between private space and the environment in which it is located. Organic architecture, in short, is this continuity that frees man but also the place in which he lives from all authoritarian constraints. One and the other complement each other, to the point that the sacrifice of one also wounds the other. Here is the new ethics of building. An ethic systematically violated, however, every day by contemporary real estate.

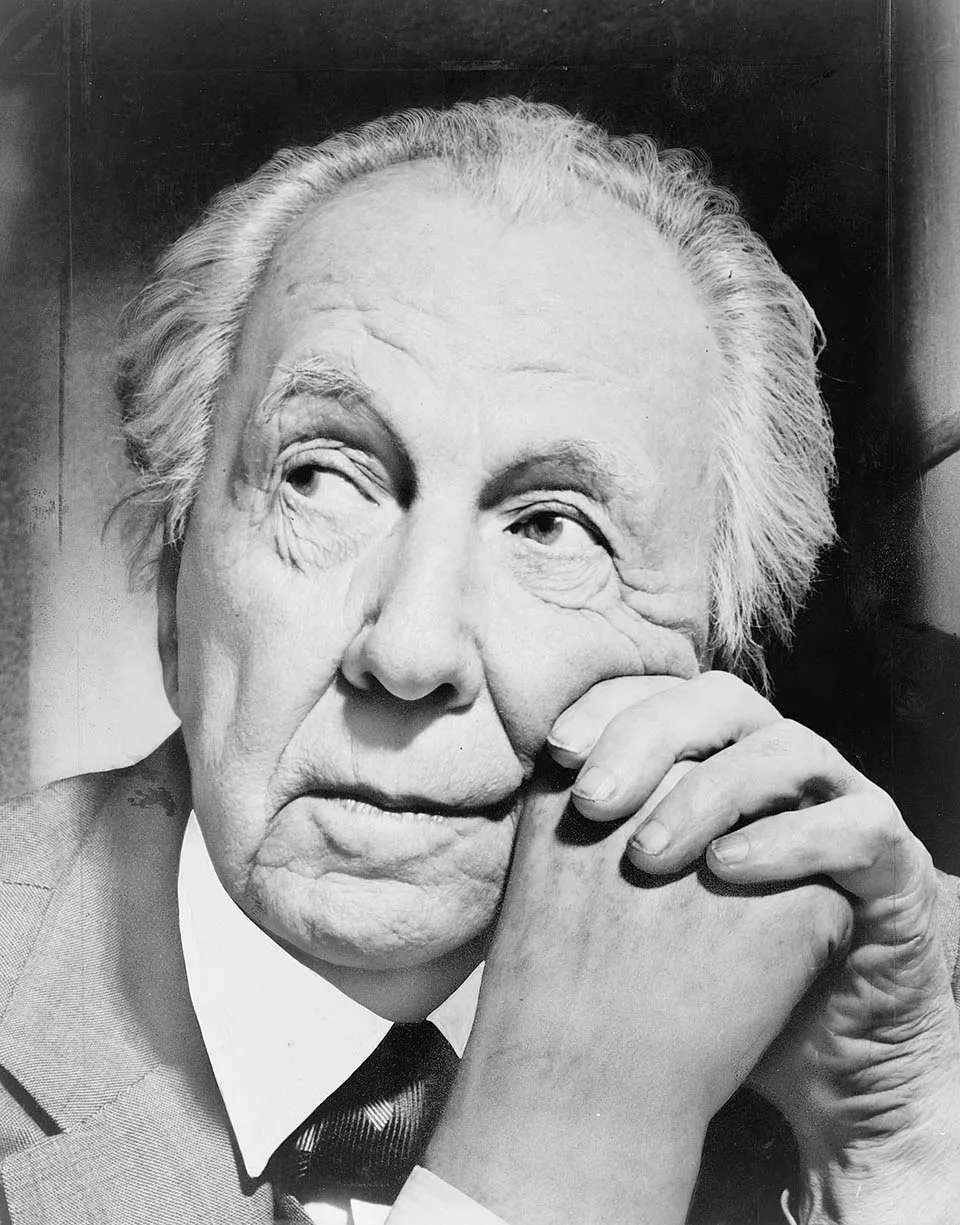

Architect Carlo Nardi has just published an erratic essay in search of the Ariadne’s thread that can account for what he calls The Crisis of the Prophet (Quodlibet, pages 180, euro 20). The prophet, of course, is Wright, and the “turning point” is between 1909 and 1910, when, having just passed forty, the Master left America and his family (wife and six children), his home and studio in Oak Park, a suburb of Chicago, having to his credit severalseveral buildings to his credit that would be enough, as Nardi writes, to reserve him a place in the history of American architecture; he is headed for Italy and has decided to settle between Fiesole and Florence, in the cradle of his enemy, the Renaissance, which he sees as the’apotheosis of academicism-Zevi had assimilated from the great American a culture of anti-Classicism, of rejection of symmetry and an abstract order corresponding to classical harmony, and from this aesthetic “hatred,” after the war had ended, he had spread the Wrightian verb in Italy; with this courageous, and risky choice, he wanted to overcome the apathy into which he had fallen while successfully practicing his art.

Wright was not one to be content. He knew he was a genius, but above all he felt his calling, his higher investiture. “He,” writes Nardi, “proceeds by accretion in his artistic evolution, and each advancement preserves the path he has taken.” If we were to say that Wright, each time he adds a new experience or knowledge gained in the field, is merely composing a more accurate portrait of himself, we might think that this is a variant of the self-made man, but we would only stop at the surface because the “prophecy,” the one that Edoardo Persico expounded in his famous lecture, is more than a utopia, which perhaps Cartesianly could have sufficed for the modernist theorist Le Corbusier, but Wright belonged to an American lineage that had among its “fathers” Emerson and Whitman, for whom wilderness-which Nardi rightly recalls-is not civilized nature, but the wilderness that remains the genetic code of American pioneers. Good nature, to be sure, capable of enormous energies, innocent even in its own overpowering force, but not goodistic as many seem to think today who do not have the same nerve as Captain Ahab who confronts Moby Dick knowing that he must be right with that blind force because that is the task of heroes who change an era. Wright, Nardi notes, could fit precisely into the Heroes that Thomas Carlyle portrays in his book of the same name, Dante among them, and the hero precisely “is he who directs the world of his own time, capable of giant feats.”

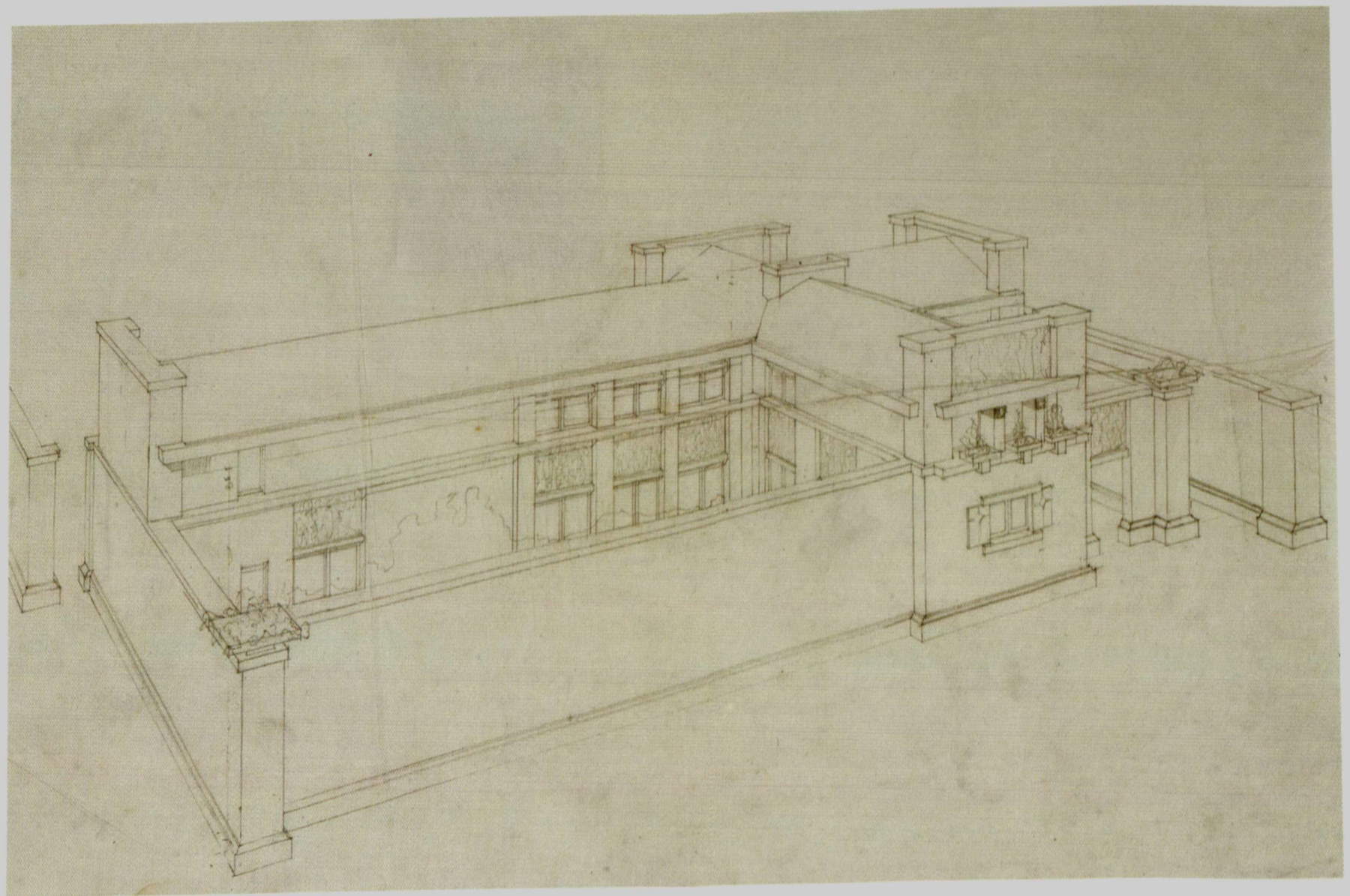

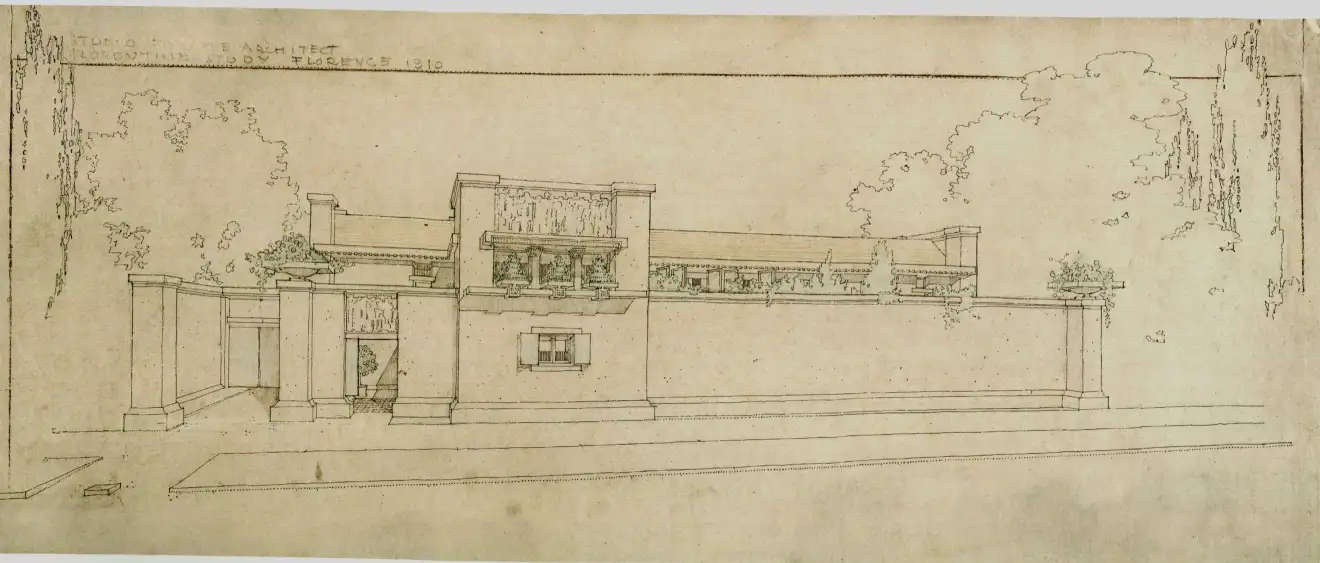

The Wrightian megalomania is a fruit of a pride in the face of which you just have to admit that he could afford it: “He did not care to see others.” Typical of geniuses, who then become heroes if they confirm expectations. Nardi evokes Melville, but sees in Hugo, in the famous antithesis ceci tuera cela in Notre-Dame de Paris, the apocalyptic witness belied by Wright’s election to the throne of “genius architect” of the 20th century. Wright does not believe that the printing press will kill architecture, quite the contrary; he himself is a strong reader, and it was during the years of his trip to Italy that he tackled a publishing project that is almost a bibliographical monument to his own genius; it is the Wasmuth Portfolio, published in Berlin in 1910, consisting of one hundred lithographic plates that gather together the catalog of his major works up to that time. Wright thus intended to prove his own predestination, which invested him with the task of revealing to Americans that a revolution was taking place and he was its word. Thus he explained to an interviewer that he borrowed the name of the Usonian Houses from Samuel Butler, who had argued that the American people had no name for their country and proposed that they be called Usonians and Usonians. There is always a foundational value in Wright’s experience, something baptismal in the biblical sense. All that remains is to recall the fatality of a fate all too diligent in making itself a myth when a fire a few years later destroyed the first Taliesin and most copies of the Portfolio.

The author of the essay pursues the faint traces of a truth written, as it were, between the lines of the Wrightian biography; he tries to get Wright to talk, hoping that he will betray himself and confess the motives that led him to that sojourn in the homeland of what he felt was smoke in his eyes: “Palladio? Bramante? Sansovino? Sculptors-all of them! Here now, instead, is Frank Lloyd Wright, the weaver.” Classicism was, in that respect, poison: however, Nardi invites us to follow the subcutaneous weave that makes the masters of the 15th and 16th centuries and the American architect “occultly akin.” One needs to be less biased: “proportion and harmony, beauty Wright would say.” Nardi had just finished observing that that early twentieth century in which Wright seeks his Thule had not yet been studied by historians such as Ackerman and Wittkover, so it would not be unreasonable to say that “in speaking of the Renaissance Wright and his colleagues had more in mind the later neoclassical and Beaux-Arts reworkings,” and not so much the masters of the Italian Quattro-Cinquecento. Yet he had named names-Palladio, Bramante, Sansovino-and compared them to sculptors. That it was a destiny of European architecture? After all, who has not thought at least once that Le Corbusier was an architect-sculptor (ever since he had conceived the Villa Savoye as a solid parallelepiped semi-suspended over the void, surrounding it in a green space at the top of a Parisian hill).

Nardi always takes Wright’s statements with a grain of salt, who weighed every word even when he was lying. In any case, the quick portrait the author gives us of the great architect is that of one who always keeps his interlocutor in his grasp, and it quickly becomes clear that no one will ever get him to say anything he has not already decided to say. To be self-confident: an imperative borrowed from Ralph Waldo Emerson, who in Self-Reliance writes: “To believe in your own thinking, to believe that what is true for you, in your own heart, is true for all men, that is genius.” Wright subscribes. And he is wary of those who attach too much weight to education, he who was not a college graduate. It is a very American, pioneering philosophy, versus the European philosophy of doubt, skepticism, of testing every time a tradition to be confirmed, albeit innovating it.

In 1909, when he left America for Italy, Wright was on the edge. In his autobiography he confesses, “Tired, I was losing my ability to work and even my interest in my work...” This moral abasement has psychological implications that require him to turn the table. He has passed his forties and realizes that what he has worked for is not enough to guarantee him that place in history that belongs to the prophets. Psychologically speaking, albeit for different reasons, it is a path that also marked the existence of another great American architect who is usually compared to him (undeservedly in my opinion), Frank O. Gehry, who sought help from psychoanalysis and then radically changed his approach to architecture, rediscovering his own condition, which in its own way was also prophetic.

In Fiesole, Nardi notes, many ramifications, even design ones, lead to Taliesin: “The Fiesole house dialogues with a different tradition from the young Prairie House... We do not find the classic fluid articulation of spaces around the central body of the fireplace. In the Fiesole house-studio the spaces are organized in sequences even though there remains in the center, on the ground floor, a hall that is much more open in the communication between the courts of the house than in the communication of the covered rooms.” Having had the opportunity, now many years ago, in the very last years of his life, to meet Giovanni Michelucci twice in his home-studio in Fiesole, the description of the Wrightian house seems to me to take into account the roots of the place, and I wonder if while designing it the American architect did not take into account the typology of the Tuscan house that marks the centuries-old history of the place. Of course, without forcing Wright’s thinking, whose first goal was to translate the intuition of space into a new architecture. But, to some extent, Wright’s definition of his house in Fiesole and Taliesin as an “eagle’s nest on top of the mountain,” I think could also be applied to the house that Michelucci lived in from 1958: it had been built in the 1930s on a steep and craggy terrain, from which one can enjoy through a loggia one of the most striking views of Florence from above. On the other hand, Wright himself lived in what was known as Belvedere Villa, from whose loggia it was equally possible to overlook the Florentine panorama. At the time, the Fiesole area and the many houses scattered in it were mostly populated by foreigners. And for Wright, Nardi writes, “Fiesole was an ideal refuge as Taliesin would later be.” As much as he wanted to keep hidden the influence that his stay in Tuscany had on his design, a trace according to Nardi remains in the drawings for his sister’s house, executed in 1911, where among the cypress trees, fenced courtyards, and terraces anticipating the main building, hints return that Wright had already been able to introject by seeing Villa Medici. Did he have, in short, an interest in Florentine villas? It was vaguely felt even in the unrealized project for his Fiesole house-studio. In Fiesole, Nardi concludes, Taliesin’s prototype took shape. And excuse me for saying so.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.