An agile book to learn about Caravaggio in Syracuse and the seventeenth-century Arethusa

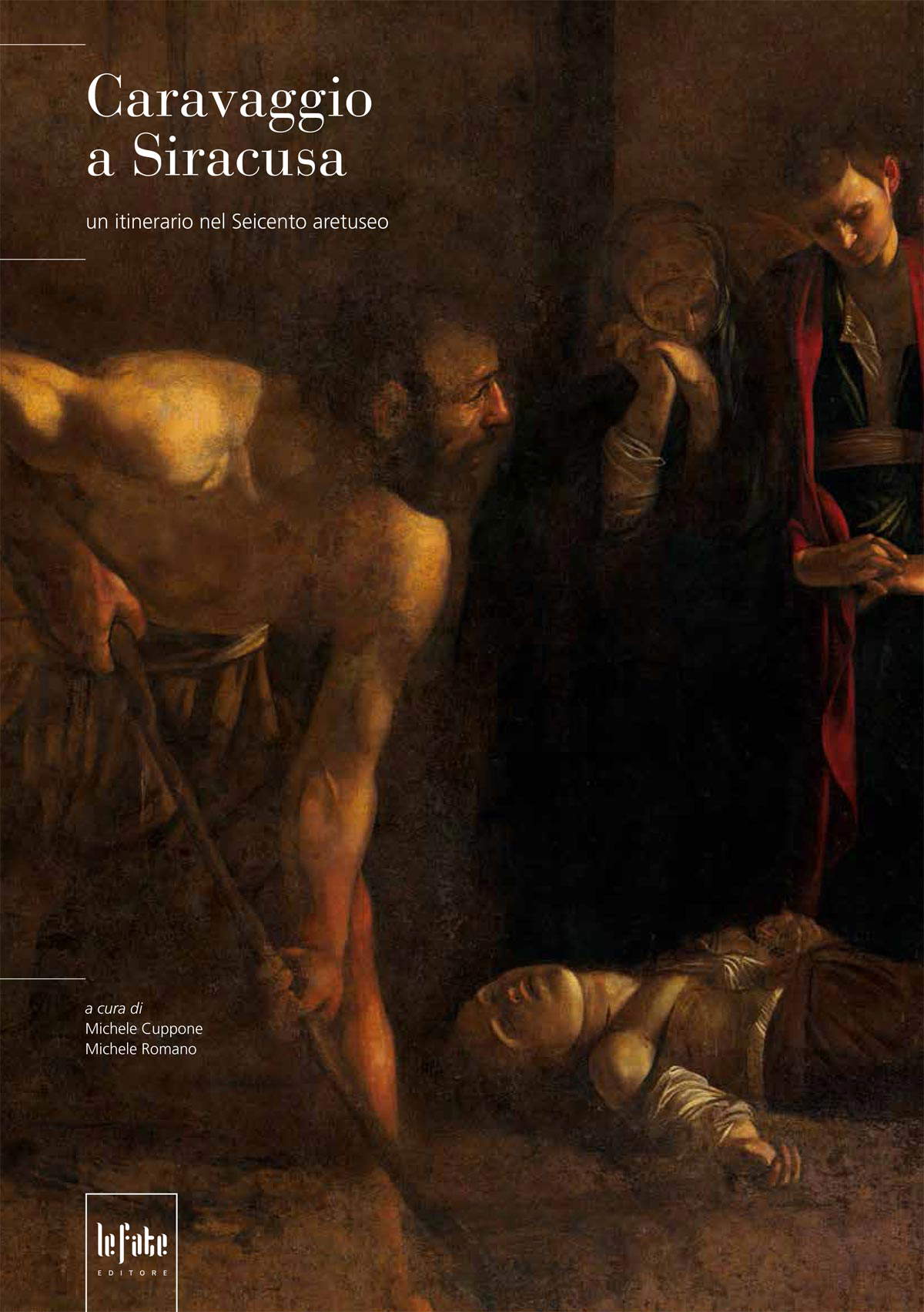

A guide and at the same time an art history book: it is an original publication Caravaggio in Syracuse. An Itinerary in the Seventeenth-Century Arethusa, edited by Michele Cuppone and Michele Romano, published by Le Fate (64 pages, 10 euros, ISBN 9788894512960), a book that intends to take the reader to discover the works of Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi; Milan, 1571 - Porto Ercole, 1610) and the artists of the seventeenth century in the city of Syracuse. A publication that thus composes a true journey among the wonders of the Sicilian city, but which also serves to take stock of the latest news concerning the Sicilian Caravaggio and, specifically, that of Syracuse, which has been talked about a lot in recent months, especially in relation to the controversy over the displacement of the Seppellimento di santa Lucia for the exhibition that would have featured it at the Mart in Rovereto (then the work returned to the city, and now it is back, after a little more than ten years, to its original location: the church of Santa Lucia extra Moenia, in the Borgata district).

“There are seven stages,” scholar Michele Cuppone explains in the volume’s introduction, “buildings almost all of which are religious and in any case in Ortigia, each of which focuses on a painting, according to a common descriptive model that pays specific attention to such non-secondary aspects as the subjects and coats of arms depicted: One cannot, after all, fully grasp the meaning and history of a painting without knowing well what it depicts and who commissioned it.” As for the names, ample space is given to Mario Minniti (Syracuse, 1577 - 1640), a friend of Caravaggio, to painters mainly active in the Syracuse area such as Daniele Monteleone, Giuseppe Reati and Onofrio Gabrieli, and finally to two additional figures who are mentioned in the appendix, namely Agostino Scilla, who frescoed the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament in the Cathedral, and Andrea Sacchi, one of the greatest exponents of seventeenth-century Roman painting, who was Scilla’s master.

|

| Book cover |

The discussion opens with a quick biography of Caravaggio, which of course focuses mostly on the Sicilian period: Caravaggio arrived on the island (in Syracuse) in 1608, after escaping from Malta, where he had become a Knight of Obedience, except that he was later arrested and imprisoned in the prison of Forte Sant’Angelo for his involvement in a violent brawl. Somehow (we don’t really know how things turned out) Merisi managed to escape from the fortress and take shelter in Syracuse, where he was the guest of his fraternal friend Minniti, who would also procure him an important commission: that of the Seppellimento for the Borgata church. The book recalls how Caravaggio also visited the latomie, and how he is credited with having coined for one of them the toponym “Ear of Dionysus” (the news is reported by local scholar Vincenzo Mirabella in his Dichiarazioni della Pianta dell’antiche Siracuse, e d’alcune scelte Medaglie d’esse, e de’ Principi che quelle possedarono of 1613). Leaving Syracuse, Caravaggio then moved to Messina where he painted the Resurrection of Lazarus and theAdoration of the Shepherds, although sources speak of a very prolific activity. Another fight, with a schoolmaster, led the painter to abandon Messina as well: the sources mention a stop in Caltagirone (where Caravaggio is said to have been fascinated by Antonello Gagini’s Madonna della Catena ) and one in Palermo, although we do not know for sure whether the painter actually passed through the capital (the Nativity in the Oratory of San Lorenzo, the painting stolen in 1969, according to the most recent studies was made in Rome in 1600 and then sent to the Sicilian city).

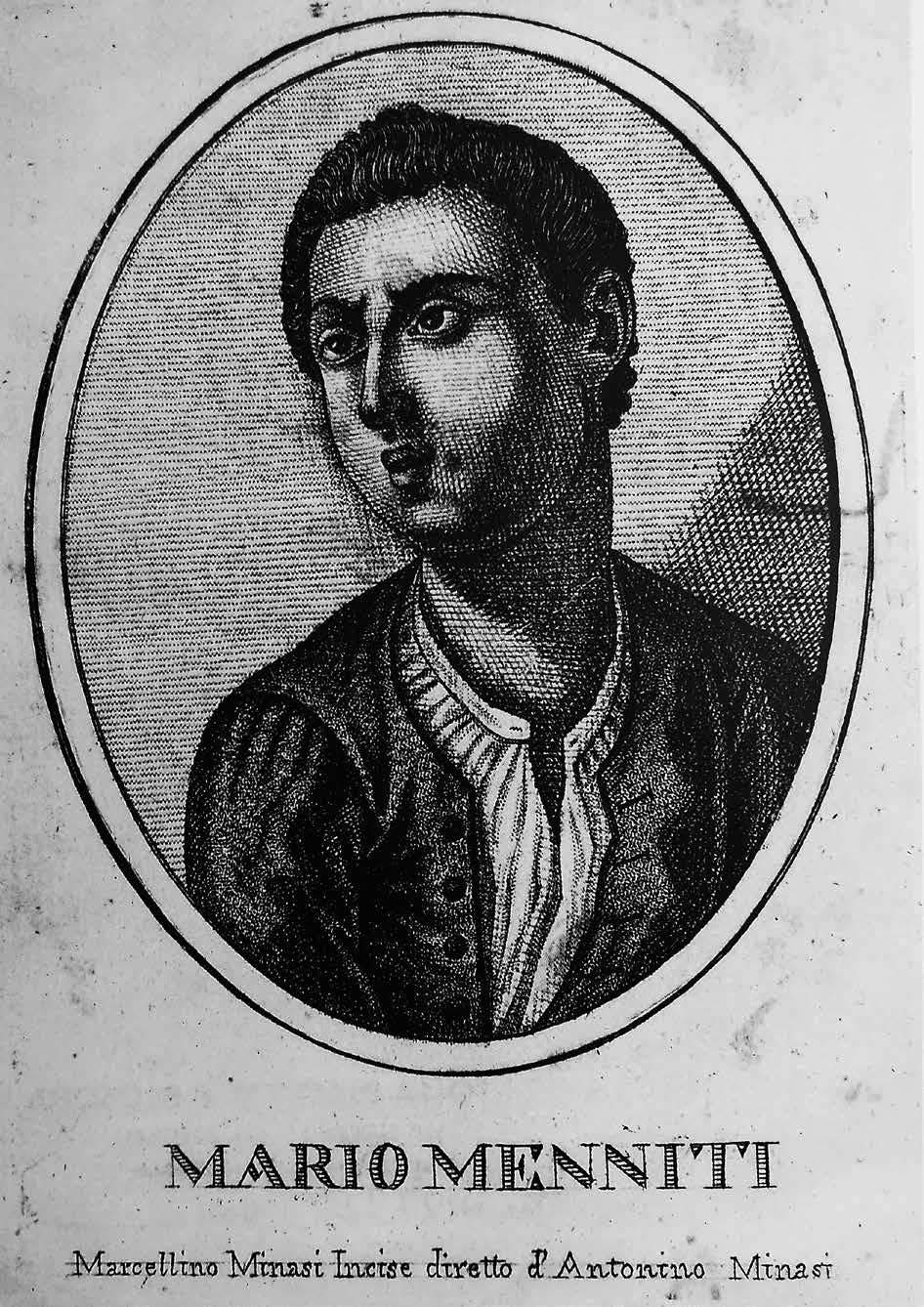

The next chapter of the book delves into the friendship between Caravaggio and Minniti: the Lombard probably met the Syracuse artist in the workshop of Lorenzo Carli, a Sicilian painter active in Rome (where he disappeared in 1597) in the late 16th century. News about the beginning of their friendship, however, is confused and second-hand: a further hypothesis has it that the two met at Palazzo Madama, where Caravaggio was a guest, starting in 1597, of his first important patron, Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte. The volume is also an opportunity to reject the conjecture that Minniti was the model for Caravaggio’s late 16th-century paintings (such as the Boy with a Basket of Fruit and the Lute Player), a hypothesis long beaten down by critics: “First of all,” Cuppone explains, "at that late date and in the absence of other known portraits of Minniti, this one could very well be of invention. But above all, the somatic features reproduced are rather vague and, therefore, comparison with Caravaggesque models is very questionable. Finally, a supposed cohabitation of Caravaggio and Minniti has offered a platform to those who claim the former’s homosexuality. The conclusion, which of course neither adds to nor detracts from the value of the great Lombard, is in any case not supported by the documents, from which the female acquaintances of both the one and the other are nonetheless evident." From documents, if anything, we know that Minniti was married (on February 2, 1601, to Alessandra Bertoldi). Fragmentary, too, are the news about the friendship, but from the little we have we can still assume a particularly close relationship to the point that, when Caravaggio arrived in Syracuse, it was his friend Minniti who welcomed him.

Cuppone’s lengthy essay on the Seppellimento di santa Lucia follows, opening with a reference to ancient, if not contemporary, sources: the earliest attestation is still Mirabella’s publication, but the primary source is Giovan Pietro Bellori, who in 1672 writes: “Having arrived in Syracuse, he made the painting for the Church of Santa Lucia, which stands outside the Marina: he painted the dead Saint with the Bishop, who blesses her; and there are two who dig up the earth with the shovel to bury her” (the most extensive account, however, is that returned by Francesco Susinno in 1724). In listing historical sources, Cuppone presents many that are little known, neglected or even misrepresented, and yet all are quite interesting. There remains the documentary vacuum that does not allow for a more precise clarification of the events that led to the birth of the painting (although one can refute the news reported in the nineteenth-century Annals of Syracuse by Giuseppe Maria Capodieci, and then reported passively by all subsequent scholars, according to which the commissioner of the work was Bishop Orosco II: going in fact to reread the original manuscript, Cuppone verified that Capodieci did not refer to Merisi, but to another, unknown artist).

|

| Caravaggio, Burial of Saint Lucy (1608; oil on canvas, 401.5 x 295.5 cm; Syracuse, Santa Lucia al Sepolcro) |

The description of the painting serves to clarify some iconographic aspects that have long been the subject of discussion. Meanwhile, the setting: Cuppone states that it is difficult to locate the scene precisely, although there have been attempts in the past to refer the Burial to real places. According to the scholar, the layout of the painting could derive from Renaissance Crucifixions: the mourning over Lucia, Cuppone writes, “in the probable presence of the mother, would echo that of St. John the Evangelist over Christ, next to the Madonna. There are in fact similarities in the characterization of the characters, where for the one in the Syracuse painting, young and glabrous [...], the traditional colors of the youngest among the Apostles are adopted. In fact, next to the more obvious red of the mantle, the green of the robe is reproposed: the latter, though in its rather dark hue, can be observed more closely in the few parts in light. Later in time, moreover, green in particular will become consolidated as associated with the saint in local devotion.” A further detail that has been the subject of long and passionate discussion is the identity of the young man in a red cloak who, with his hands intertwined, stands looking at Lucia as she is buried. Traditionally he has been identified as a deacon, since the cloak closely resembles a stole: however, it is difficult to restore an identity to this character, although Cuppone formulates a new hypothesis. According to some hagiographies, before her death St. Lucy would have been joined by the bishop of Syracuse along with the entire clericate (according to other versions of the story, along with the entire Syracuse clergy). The figure of the bishop is the one we note on the right, and therefore the young man, instead of a deacon, could be a cleric “and thus represent the Aretusean clergy, who rushed to the place of martyrdom,” Cuppone suggests, wishing for further investigation of this idea, and while acknowledging that the observations of the robes worn by the young man would seem not to completely support the hypothesis. Finally, one last element to discuss is the figure in arms, sometimes identified as the prefect Pascasius, who condemned the saint to torture: however, according to some hagiographies the prefect was himself condemned before the saint suffered martyrdom. If Caravaggio followed these sources, the identification can therefore be refuted.

The book is also an opportunity to summarize the painting’s state of preservation, a topic of close concern (the work was also the subject of an examination by the Central Institute for Restoration in Rome in June 2020, which found that the painting was in a state described as “fair” last summer, but was still in need of maintenance). However, the canvas has suffered greatly (it is perhaps Caravaggio’s most battered work), due to the humid environment in which it has been stored for centuries, and ancient tampering. “Several faces of characters and other details,” Cuppone recalls, “are no longer the original ones: having been lost, we see the remaking of them from the oldest restorations. In the canvas that has also come down to us, we might say, battered, Lucia is best preserved for the upper half of the body. The rest, is now evanescent to the point that, unintentionally, the sense of resignation and disquiet that the painting conveys is amplified.” All antique copies of the work are then listed, demonstrating the extraordinary success of Caravaggio’s masterpiece.

|

| Marcellino Minasi, Portrait of Mario Minniti, published in G. Grosso Cacopardo, Memorie de’ pittori messinesi e degli esteri che in Messina fiorirono dal secolo XII sino al secolo XIX, Messina 1821 |

There is also space in the book for a biography of Mario Minniti, written by Nicosetta Roio. Minniti, who was born in Syracuse in 1577, left his hometown around 1592, escaping on a galley of the Knights of Malta (although we do not know why), and took shelter in Malta itself, likely protected by the knights. According to Roio, on the island Minniti would have gained his first artistic experiences, training with the Florentine Filippo Paladini, who had been present in Malta since about 1590. Leaving the Mediterranean island, Minniti arrived in Rome, probably between 1595 and 1596, a period when Caravaggio also began to be mentioned in Roman documents. “In the Urbe,” Roio writes, “Minniti’s passion for drawing had not diminished; indeed, it seems that he practiced it at night, giving up sleep, in order to make up for the time he considered wasted during the day ’roughing out paintings,’ even though that uncreative work gave him a living. Together with his Lombard friend, he happened to work for other similar artist-entrepreneurs in the same neighborhood; later, although still ’poor’” they would move in together, abandoning Lorenzo Carli’s workshop, and begin to frequent Cavalier d’Arpino’s circle. Minniti’s stay in Rome lasted ten years (during which, as mentioned, he also got to marry): he is again attested in Sicily in 1605, in January, according to a document recently published by Cuppone. Between 1608 and 1614 there is a lack of documents attesting Minniti’s presence in Sicily: he probably made several returns to Malta during these years. However, in Sicily the artist rediscovered Paladini and revisited his style, moving toward “simple and quiet atmospheres emotionally linked to the Baroque and Roman post-Raphaelesque world of Cavalier d’Arpino, while the connection of his paintings with the powerful expressiveness of Caravaggio is more superficial.” A prolific artist, although, Roio notes, the quantity of his output was not matched by a consistent level of quality (a characteristic already pointed out by ancient sources), Minniti worked until 1637, the year in which his last work is documented, and died in Syracuse on November 22, 1640.

After Minniti’s biography, the “guide” to Syracuse’s artistic itinerary begins, complete with a map showing the reader the location of sites to visit. The long section on theitinerary of the seventeenth-century Arethusa is entrusted to Michele Romano, whose itinerary includes the churches of San Benedetto, Santa Maria della Concezione, San Filippo Neri, San Pietro al Carmine, Santa Lucia alla Badia, the Regional Gallery of Palazzo Bellomo and the Jesuit College, and then again the Cathedral, the Basilica of Santa Lucia al Sepolcro and the Latomia del Paradiso (otherwise known by the famous toponym “Ear of Dionysus”). For each of the places, the works present are indicated, each with a relative card that provides historical news, information on the subject, analysis of the work, and bibliographical references: the names range from Mario Minniti to Daniele Monteleone, from Giuseppe Reati to Onofrio Gabrieli.

Agile, practical handbook within everyone’s reach, an inexpensive guide for the educated traveler eager to delve deeper, a summary of the events of the seventeenth-century Aretusean period, a lunge on Caravaggio’s Syracuse sojourn: anoperation of sure interest, perhaps to be replicated for other destinations.

|

| An agile book to learn about Caravaggio in Syracuse and the seventeenth-century Arethusa |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.