A rebirth under the banner of art (and Beuys). Lucrezia De Domizio Durini's new book.

Shame and Truth is the title of the impressive book Lucrezia De Domizio Durini is publishing with Mondadori (288 pages, €19.90, ISBN 9788891832849) on the centenary of Joseph Beuys’ birth. It is difficult to briefly summarize the book’s topics: it is a sort of stream of consciousness of the author on a wide spectrum of issues (from politics to the media, from religion to globalization, passing through culture and art), continuously innervated by the reflections of Beuys, of whom De Domizio Durini was a student (today she is among his greatest exegetes: she has devoted a lifetime to the study and dissemination of Beuys’ art and thought). Lucrezia De Domizio Durini describes herself as an “atypical character in the contemporary art system”: active for more than forty years, she was the head of Studio L.D. which she founded (a house-gallery that in the 1960s offered exhibitions of Burri, Fontana, Capogrossi, Rotella, Pistoletto, American Pop Art and Constructivism), a collaborator of the leading exponents of Arte Povera and Italian Conceptual Art, a journalist, publisher, collector, writer, author of thirty-three books on Beuys, and curator of exhibitions.

What is the reason for such a composite publication? “To bring to light the hardships of a life of continuous struggles,” says De Domizio Durini, particularly of women who have suffered abuse: the author’s is therefore, first and foremost, a journey into the slums of Italy, among corruption, political malaise, the poor treatment to which culture is subjected, and what the author believes is one of the evils of our country, namely the failure to recognize "merit." After a first chapter of an intimate and biographical nature, the author begins her personal journey to hell, starting with politics: “If we look carefully at how much care the holders of any kind of power put into social conventions, we notice how they discard merit from all important positions where instead specific qualities and skills would benefit Society,” writes the scholar, according to which a kind of “genocide” of young people and all those who try to change things would be inact. Nepotism, lack of secular culture, false ideology, Church conditioning are, in her opinion, the main problems. And all this despite the fact that politics is one of the noblest disciplines. What to do in such a scenario? De Domizio Durini indicates some points: the rediscovery of compromise (seen, of course, in a positive sense), intellectual integrity, and the revaluation of culture and art. It is still Beuys, according to the author, who points the way: “When we have the consciousness of all working together as free individuals we are much closer to having created a real and concrete democracy.” “I believe that true politics, the healthy kind,” the author writes, “must be an exemplary art by which men associate with each other for the purpose of establishing, cultivating and preserving among themselves a social life made up of solidary cooperation among all classes of society.”

|

| The book cover |

In De Domizio Durini’s analysis there is room for the press and the media (“only a free and unrestricted press can effectively denounce the deceptions of those bosses who hold dark power, since freedom of expression is the basis of human rights, it is the root of human nature and also the mother of truth”), ecology (Beuys’ Defense of Nature is called into question, which proposed an anthropological vision, a change in the perception of human values, a union among all human beings under the banner of connection with nature and the cosmos), and economics. The text is also interspersed with essays by third-party authors: present, for example, is an insightful contribution by Vitantonio Russo on the topic of Beuys and the economy. On the topic of globalization, the author includes in the book an interview by Lukasz Galecki with Zygmunt Bauman. An extensive reflection by Lucrezia De Domizio Durini is devoted to the theme of home, a kind of basis for a new value system based on culture: the author’s idea is that contemporary culture has embedded the end of modernity in the metaphor of dissolution, of the liquefaction of twentieth-century structures, making our time “a liquid age and fixing its course in the image of a fluidity in which everyday existence has been mirrored starting from its most obvious manifestations of living, of conceiving everyday life, the relationship with time, with personal relationships and with the greed for money.” The current experience of living thus reflects this frenetic world that seems to be founded on mutation: but in the future, living will continue to be an experience deeply rooted in human nature, impossible to change. Culture is also part of human nature: “it contributes both to the individual’s intellectual and moral formation and to the acquisition of an awareness of his or her role in society,” the author writes. “It embraces notions, beliefs, arts, customs, habits, traditions that are proper to man as a member of society. We might also add that it is in opposition to the concept of nature, understood as a cosmic totality, visible and invisible, regulated by physical and biological laws, within which man is immersed.”

The idea of culture as civic consciousness underlies the proposal to totally rethink our educational system, since education is the fundamental body of a civilized nation, to embrace a paradigm based on passionate love, deep competence, learning not in the name of “business” but of knowledge and quality of life, and above all a system based on creativity, as was what Beuys envisioned (his ideas on education are quoted with extensive excerpts). Lucrezia De Domizio Durini’s j’accuse then turns to governments that are guilty of allocating few resources to research: “governments,” she says, have not understood the value of research “and have not understood that in this historical moment research needs multidisciplinary teams and transnational networks. Moreover, the scarce economic resources available in Italy are fragmented into many ministries at odds with each other and with a phantom Ministry of Research over which politicians have no ability to coordinate, much less expertise because they are totally incongruent and power-hungry.”

|

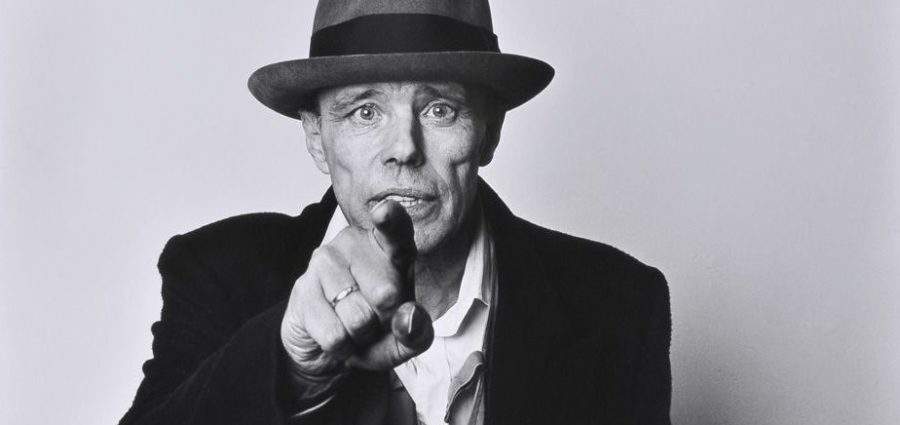

| Joseph Beuys |

An entire chapter, entitled Veritas filia temporis, is dedicated to reflections on religion (and in particular on Christian thought, the Church, and certain figures such as those of Celestine V and Pope Francis), leading to the last part of the book in which the author hopes for a rebirth in the sign of art (without sparing the current contemporary art world any criticism: according to the author, the propulsive thrust of creativity ended in the 1970s, and after this period politics and money prevailed even in art). For De Domizio Durini, artists play a key role in the transformation of society: “The Artist is the one who places Art to play the central function in our lives, a function that first of all changes the way we live, think, and see. A change of radical and endless dynamism and learning. The Artist today must be at the Service of Society for the betterment of human life.” There are two necessities that, according to the author, 21st-century art demands of the artist: the vivification of the spirit (thus a true and innovative art that avoids the déjà vu of televisions, that avoids recording the everydayness of the street or advertising or fashion magazines) and the confrontation between artists of different nations, generational states, of different researches, bound together by a strong sense of respect for the fundamental principles of Man and his Mother Nature. Only from these assumptions, according to the writer, can art reflect on the present time. “An artist,” the author argues, “cannot be asked to amaze us with his fertile imagination, but to engage us with his thinking and behavior. It can, indeed must be a lookout in which ethics must mark a moral encroachment into the order of authentic knowledge in order not to depend on the law of instincts and to proceed carrying the load of the Absolute and the Infinite.”

A continuous flow of thoughts, a non-organic but strong treatment by a woman who, now almost in her nineties, still intends to put herself on the line to spread Beuys’ thought (which she considers a beacon for the future as well) and to continue her struggle against abuse and power groups.

|

| A rebirth under the banner of art (and Beuys). Lucrezia De Domizio Durini's new book. |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.