Correggio is one of the greatest painters in history: this is the seemingly trivial starting point from which the most recent monograph on Antonio Allegri, Correggio. The Genius, the Works, by Giuseppe Adani, published by Silvana Editoriale. An art historian deeply in love with his city and with the painter, to whom he has devoted almost his entire career, Giuseppe Adani summarizes in this volume the latest results of prolific research on the artist, offering readers an updated monograph that takes into account the work done by scholars on Correggio over the past 12 years: the major exhibition at the Galleria Nazionale di Parma (2008-2009), the shows at the Galleria Borghese (2008) and Venaria Reale (2010), the one that featured him together with Parmigianino at the Scuderie del Quirinale (2016), the 2008 conference, and the rediscovery of the Sant’Agata di Senigallia, exhibited between 2018 and 2019 in the Marche city and in Correggio. A great amount of studies that finds therefore an adequate arrangement in this book, strengthened by a rich and complete iconographic apparatus.

Leafing through the thick volume, dedicated to Eugenio Riccomini, one will find that it lacks the rigorous systematics that is typical of scientific treatises: it will be difficult, for example, to find insights into the debates around the dating of the works, or complete records on the transfers of ownership (although there is also no shortage of moments of greater verticality: for example, when talking about the aforementioned Saint Agatha, or the Portrait of a Gentlewoman from the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, the subject of recent in-depth studies). Adani convincingly explains these absences: first, it would have been a matter of re-proposing data already acquired. Secondly, the author’s precise intention is to produce a more open and almost colloquial essay, without renouncing the scientific rigor that befits such a work. Correggio. Il genio, le opere is thus to be read above all as a monograph of didactic and educational value, organized with great clarity according to a chronological arrangement of the stages of Antonio Allegri’s career.

The one proposed by Adani is thus a sort of guided journey through Correggio’s production: a journey that combines moments in which the treatment becomes more pressing (but where he does not skimp on references to the conspicuous bibliography on the artist), and prolonged pauses. The reader realizes this right from the first two chapters: the beginning of the itinerary coincides with Correggio’s training: this is now one of the most frequented territories of the artist’s career, and consequently Adani dwells on the early stages of Correggio’s production just long enough to provide the reader with an overview, obviously accurate (with fact sheets devoted to individual works, as is the case throughout the book), and a few summary pages. On the other hand, the approach is different for the next chapter, devoted to a single episode in Correggio’s art, namely his presence inside the monastery of Polirone in San Benedetto Po, the longest chapter in the book after the chapter on the Parma works of 1519-1521 and the chapter on the period 1522-1533.

|

| The cover of the book Correggio. The genius, the works of Giuseppe Adani |

The need for a lunge on the Polyronian period is motivated by the fact that, in recent years, Correggio’s sojourn on the banks of the Po has been the subject of varied attention by critics (one has returned to talk about it, for example, in the important exhibition on the sixteenth century in Polirone that was held precisely between the refectory and the Polironian basilica, from September 2019 to January 2020), and the need therefore arose to give an account of the latest acquisitions on the Polirone enterprise. An affair that, moreover, comes on the heels of Correggio’s trip to Rome, which Adani, on the basis of the most recent studies, imagines as accomplished by the painter both to fine-tune a more tenacious “conquest of the modes and compositions of painting,” and to mentally prepare himself for the refectory wall at the Polirone: “a task,” the author writes, “that caused a sort of special anthology to accumulate in the travel notebook of the still young artist, who (let us not forget) was accompanied by the learned Gregorio Cortese, his mentor and advisor.” Cortese, moreover, had in mind to call Raphael to fresco the entire wall: having failed in his intention to call the Urbinate, he would resolve to make up for it with a “Parrhasius futurus” identified precisely in the young Correggio (then about 25 years old: he was six years younger than Raphael), who frescoed the wall on which Girolamo Bonsignori’sLast Supper was later installed (an unusual choice, that of inserting an oil painting inside the wall, but not unique). The chapter on the Polirone fresco then goes on to analyze the theological and iconographic themes of the wall, even focusing on individual details, functional to emphasize certain aspects of the decorative program. And details from which, moreover, emerge an already very up-to-date painter, capable of renewing his Mantegna training by looking to the Venetian painting of Bellini, Montagna and Cima da Conegliano as well as to the Umbrian painting of Perugino.

On the contents of the iconographic program, Adani also proposes some new hypotheses: besides reaffirming the attribution to Correggio of the entire frescoed ensemble (there have been doubts in the past, which the author motivates mainly because of the particularly distressed conservation conditions of the wall), the art historian focuses on some figures (such as those of the prophets Isaiah, Abraham and Melchizedek), which in his view corroborate the idea of the theme of waiting according to the Jewish line and according to the Gentile line, both concerning prophecy and foreknowledge in the expectation of the incarnation of the Word. This is not, however, the only proposal the reader will find in the discussion, which after the part devoted to the Polironian frescoes continues with the early maturity (1513-1518) and the early Parma years. In this last chapter, which deals with topics such as the Camera di San Paolo and the frescoes of San Giovanni Evangelista, we return to the Portrait of a Gentlewoman in the Hermitage, for which Adani reiterates the idea, recently suggested by him, that it is the portrait of Veronica Gàmbara, countess of Correggio, wife of Count Giberto X. Adani confirms in the book a date at the end of 1520 in agreement with David Ekserdjian: Correggio, in fact, is documented in his hometown from October of that year (the time of his return from Parma where he waited for the realization of the frescoes of the dome of San Giovanni) until March 17 of the following year (moreover, at the same time, he married Jeronima in Correggio). This long stay, according to Adani, “allowed him the careful preparation and repeated poses necessary for the execution of the portrait, which was required of him by the family and political circumstances of the countess; she, after the death of her beloved husband Giberto X [which occurred in 1518, ed.], had in fact provided for the request for confirmation of the imperial recognition of her state with the young emperor Charles V, aimed at obtaining the principal investiture for her own minor children. The announcement of the document’s arrival set in motion a fervent preparation by the court of Correggio for the related celebrations, and the Imperial Diploma in fact arrived on December 16, 1520 specifying Veronica’s own role as Regent until the eldest son Ippolito came of age.” These circumstances, according to Adani, would justify the execution of the portrait and also motivate its majestic character and exceptional size.

Among the most interesting moments of the book, it traces, for example, the reconstruction of the Triptych of Mercy (executed for the church of Santa Maria della Misericordia in Correggio), which was singularly supposed to contain also a terracotta Madonna and Child and which in the upper part saw the presence of a Christ the Redeemer in Glory now in the Pinacoteca Vaticana and recognized as a Correggio autograph in 2008 by Giuseppe Adani and Rodolfo Papa: here, Adani reaffirms its attribution to Correggio. And again, an absolute novelty in the volume is the proposal to identify the Magdalena leggente from a private collection as the last painting by Antonio Allegri made in 1533 on commission from Isabella d’Este: the book gives an account of the discovery for the first time, and Adani anticipates that a study entirely devoted to the painting is forthcoming, which will be the result of a decade of studyî and to which Marzio Dall’Acqua, Ines Agostinelli, Adrián Egea and Antonio Guerra will contribute. In Correggio. The Genius, the Works only a few brief anticipations are given, postponing everything until the next publication, since the issues to be addressed are very extensive. There is then a way to reiterate Correggio’s autograph authorship of the Pieta in the Museo Civico di Correggio, a work attributed to the artist initially by David Alan Brown, then by Eugenio Riccomini, and then exhibited (also there as an autograph) at the major 2016 Scuderie del Quirinale exhibition curated by David Ekserdjian, and of the Young Man Escaping the Capture of Christ, a painting first proposed as a Correggio work in 2013 by Elisabetta Fadda and Nicholas Turner and also featured in the catalog at the 2016 exhibition. Finally, the dating to 1530 as the beginning of the frescoes in Parma Cathedral is convincingly affirmed on the basis of Cristina Cecchinelli’s studies: a dating that, according to Adani, should now enter definitively into a monograph specifically dedicated to this greatest undertaking of the artist.

|

| Correggio, Architectural Setting of the Last Supper by Girolamo Bonsignori (1513; fresco and dry interventions, 1170 x 1135 cm; San Benedetto Po, Refettorio Grande) |

|

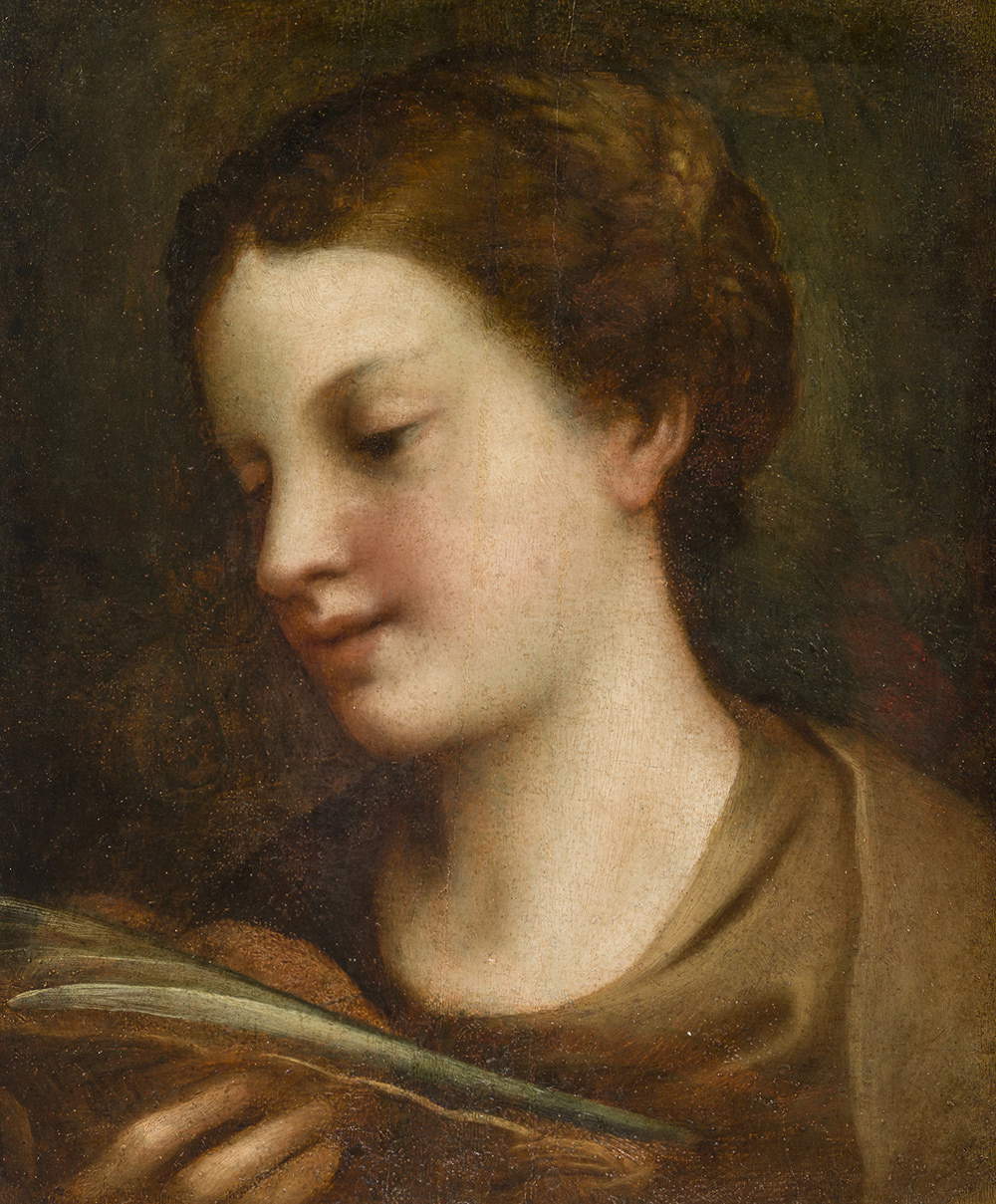

| Correggio, Portrait of a Gentlewoman or Portrait of Veronica Gambara (1520; oil on canvas, 103 x 87.5 cm; St. Petersburg, Hermitage) |

|

| Correggio, Redeemer in Glory with Angels (1522-1524; oil on canvas, 105 x 98 cm; Vatican City, Vatican Museums, Pinacoteca Vaticana) |

|

| The frescoes of the dome of San Giovanni in Parma |

|

| Correggio, Saint Agatha (1525-1528; oil on panel, 29 x 34 cm; private collection) |

|

| Correggio, Maddalena leggente (1533; oil on canvas, 38.6 x 59.2 cm; Madrid, private collection) |

Chapters on religious paintings, on the Mantuan period in the service of Isabella d’Este, on the 1522-1523 period, on the cycle of the Loves of Jupiter and on the other frescoes in Parma, including the Camera di San Paolo, complete the volume, ending with some brief chronological notes and a reference bibliography, including volumes that have made the history of scholarly literature on Correggio and the latest acquisitions: the sections thus more “palatable,” so to speak, for critics, are flanked throughout the book by more popular occasions for the reader who wants to approach Correggio’s art in order to understand that greatness reiterated by Adani in the opening.

Correggio. The Genius, the Works comes out on the important occasion of Parma Italian Capital of Culture, a title the Emilian city will boast of in 2020 and again in 2021: an event that, so far, has not, however, offered any incursion on Correggio, despite the fact that Parma was to Correggio, given due proportions, what Rome was to Raphael (this is what Giuseppe Adani also asserts in the book), especially since Parma was at the time a city of just sixteen thousand inhabitants, but nonetheless was able to follow up on artistic endeavors of exceptional importance. It would, moreover, be a “round” anniversary, so to speak, since 2020 marks exactly five hundred years since the execution of the San Giovanni Evangelista frescoes (one of Correggio’s fundamental masterpieces, reproduced in all school textbooks of art history). The excellent book thus comes to fill a little of the Correggio gap that even RAI Cultura is now actively addressing. And it arrives, above all, to anticipate future developments on the studies around the artist: Giuseppe Adani anticipates, for example, that the news has been discovered that Bernardo Cles, commissioner of the Romanino Loggia in the Buonconsiglio Castle, had tried to get Correggio to do some work in the castle. And again, it will be noted that the book omits Correggio’s graphic production: for the author, a “regret” due to editorial needs, but also the stimulus for a future dedicated publication. Correggio, after all, is an artist on whom the attention of critics is very much alive and who will still be able to reserve many surprises in the future.

|

| A new monograph by Giuseppe Adani is released for Correggio, with some previously unpublished submissions |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.