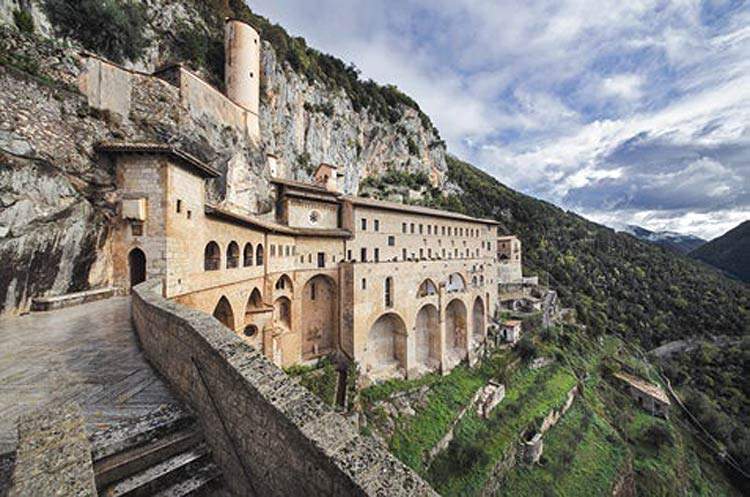

An important volume entirely dedicated to the Sacro Speco of Subiaco, the monastery of St. Benedict not far from Rome, was published by Mandragora a few weeks ago: the work of the young scholar Virginia Caramico, born in 1989, the book is entitled Il Sacro Speco di Subiaco illustrato. Sacred Topography and Narrative in Images between the Two and Fourteenth Centuries (228 pages, 50 euros, ISBN 9788874615506) and stems from the author’s doctoral research at the University of Florence, in cotutorship with the University of Lausanne. The full-bodied volume traces the ancient events of the important monastic complex through the analysis of the pictorial decoration of the 13th and 14th centuries present in the “crypt” (the term with which Caramico, for reasons of greater clarity and historical correctness supported by the sources, preferred to define what tradition identified as the “lower church”) and in the church (i.e., the “upper church”) of the Sacro Speco. Not an easy goal, given the intricate historical events that have affected the Sacro Speco and left their mark on the complex: when one enters the sanctuary, writes art historian Andrea De Marchi in the presentation, “one has the impression of finding a small Assisi nestled in the mountain, in the squaring of ambitious multi-layered pictorial cycles, with the stories of the Passion of Christ, of the Virgin and of the Infancy of Christ, of St. Benedict.” Today, moreover, an inverted route is taken compared to the one pilgrims followed in ancient times: in fact, one begins in the chapter house frescoed by Cola dell’Amatrice, enters the hall decorated with the Stories of the Passion by an anonymous painter from Perugia who worked around 1340, and then descends to the oldest part, the one that includes the small sacellum of St. Gregory, the original nucleus of the Sacro Speco.

Instead, Caramico’s research showed that pilgrims entered from the lower part, reasoning that to them “an anabasis was envisaged,” explains De Marchi, “from the bowels of the rock up to the luminous western cross with the Stories of the Passion, whose function as a back porch reserved for the black monks who resided at the Speco is finally clarified.” It is precisely through the reading of the works, from the decorative cycles and their arrangement in the spaces of the monastery, that Caramico has reconstructed the itinerary of the ancient pilgrims: an acquisition of primary importance, since it has led to a correct understanding of the succession of the decorative cycles of the Sacred Speco. And to lead the reader through this journey through the Sacro Speco, the book also makes use of a very rich iconographic apparatus, complete with an initial atlas that follows the order of the rooms according to the route followed by those who visited there in ancient times. The structure of the text also follows a chronological order but without interrupting the division between lower and upper rooms where necessary.

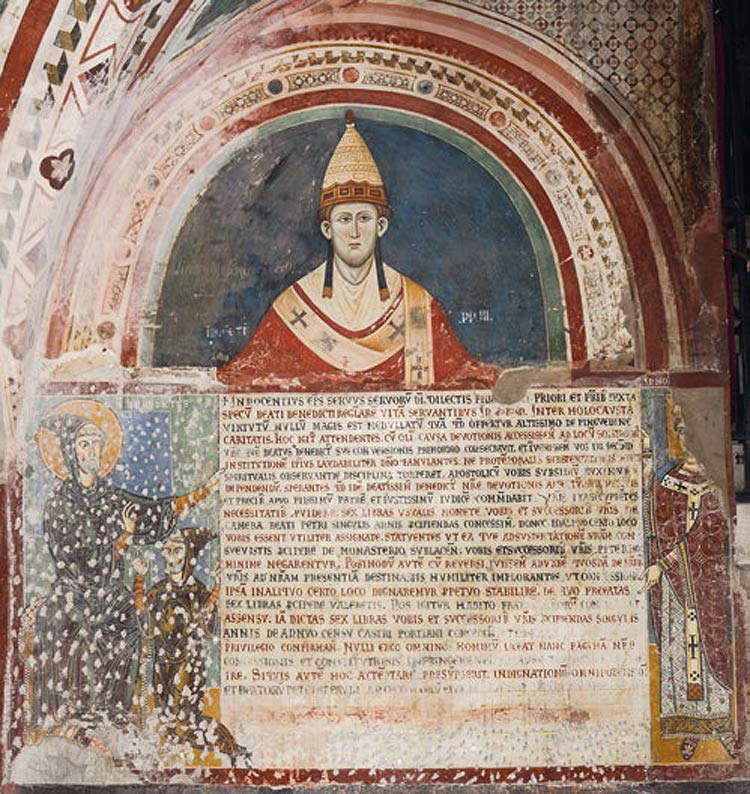

Already in ancient times the two caves, that of the Speco where St. Benedict had lived for three years, and that of the shepherds, were sacred places, as attested by the altars raised along the “Holy Stairs” (the path that joined the two caves) between the 9th and 11th centuries. And around the caves would soon arise a system of cells where all monks who obtained permission from the abbot of the nearby monastery of St. Scholastica led hermitic lives. The first attempts to give an organic architectural arrangement to the place failed because of the ruggedness of the territory, but the situation changed when, in 1203, Pope Innocent III, with one of his bulls, granted the papal privilege to the Speco allowing the formation of a stable monastic community that followed the Rule of St. Benedict and opening to the attribution to the Benedictines of a patrimonial endowment with which it was possible to start the first architectural interventions. It began with the remaking of the already existing rooms, aimed at ensuring structural continuity: in particular, the action focused on the Porta Sancti Benedicti and the adjoining rooms, i.e., those first encountered on the way up from St. Scholastica and beginning the path to the Speco cave. At the same time, decoration work began: the oldest are those on the southern front, dating from between 1203 and 1219. Of particular note is the fresco depicting the Donation of the Privilege of Innocent III, the founding act of the coenoby, attributed to a Roman painter of the first decade of the thirteenth century, with later reworkings by the magister Conxolus who intervened on the work almost a century later. Then dates back to the early thirteenth century the construction of the chapel of St. Gregory (it was “located in the most secluded and dislocated position in Specuense topography,” writes Caramico: it is in fact located to the south of the Oratory of Our Lady, at the end of a long elevated corridor), frescoed in 1228 (the author places the creation of the frescoes in a period between March 1228 and the canonization of St. Francis, which took place in July of the same year: in the decoration we note in fact the saint without a halo), and consecrated in the same period. The frescoes in this case are the work of an anonymous painter identified as the “third master of Anagni.”

The chapel of St. Gregory (the titling is due in part to the fact that it was built under the pontificate of Gregory IX, and in part, and above all, to the spread of the cult of St. Gregory the Great among the Benedictines) was located in a spot of the monastery that was difficult to access, which therefore kept it secluded, but we do not know for sure what its original purpose was. However, for Caramico, the importance of the place is linked to the “indulgences with which the Gregorian altar was endowed from its foundation and which were to become more conspicuous in time; also striking is the special regard of the monks for the little temple, such that they addressed insistent prayers to the pope that he would give the place a more solemn consecration.” Indeed, the iconographic reading proposed by Caramico focuses on the themes of memory and penance, as attested by various figures of devotees invoking angels and saints for salvatio animae. Symbolic implications announced by the fresco outside the chapel with St. Gregory the Great with the plagued Job, where Gregory the Great’s activity as commentator of the Old Testament is paid homage (to the saint, Caramico writes, “an early normalization of the funerary liturgy as an instrument of redemption and a decisive affirmation of the value of pro animis prayer” are to be credited). The book thus analyzes in detail the doctrinal implications of the frescoes in St. Gregory’s chapel. A novelty proposed by Caramico is the attribution to the Third Master of Anagni of the St. Benedict on the southern facade of the Speco complex, a work in the open air and therefore affected by weathering over the centuries, which can be traced on a stylistic basis back to the author of the frescoes in the Gregorian sacellum.

Subiaco,

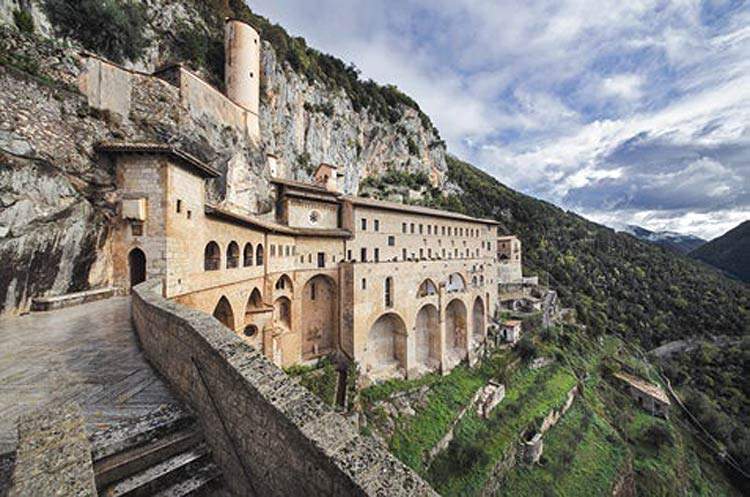

Subiaco, Subiaco, Monastery of the Sacred Speco, view of the

Subiaco, Monastery of the Sacred Speco, view of theThe main novelties in Caramico’s study, however, concern the work that affected the Speco at the end of the 13th century, a time when the crypt was probably completed. Until then, the path of access to the Speco began at the Porta Sancti Benedicti, continued along the back of the Holy Staircase and reached the fresco with the Donation. Later, however, new interventions determined a rearrangement: the Stairway was divided into two segments that produced alterations to the crypt as well. The works provided the grotto of St. Benedict with direct access, but they would probably have provided direct access to the Gregorian chapel as well, given its importance “in the context of a progressive endowment of indulgences of the altars located in the crypt, a circumstance that could not but determine an opening of the sacellum to more consistent flows of devotion, programmatically directed at all the altars of the Speco.”

It then moves on to an in-depth analysis of the Stories of St. Benedict in the crypt, the work of the Conxolus who remodeled the frescoes in the sacellum of St. Gregory, whose name represents a rarity for the Speco, and who may have worked at a time not far from that in which the Stories of St. Francis in Assisi were executed, between 1292 and the end of the century. After clarifying the stylistic framing of the stories and the hands that worked on them, the author of the book goes on to carefully investigate the reasons for and specifics of the fourteen stories that make up the cycle and that recount episodes related to the Sublacensis experience of St. Benedict, celebrated in such a lofty manner probably also by virtue of what was happening in the same years in Assisi for St. Francis. Many elements are relevant: the strong public connotation of the cycle, intended for the part of the complex where the faithful flocked most heavily, the breadth of the Conxolus narrative, and the integration with the ornamental apparatus. The arrangement of the episodes also supports the hypothesis that at the end of the thirteenth century the visit to the crypt could take place both up and down, albeit with a narrative sequence designed to “better accommodate the paths of lay and monastic devotion that began at the raised level of the crypt.” The beginning thus coincided with the scenes of the Miracle of the Sifter, the Dressing of St. Benedict and the Saint in the Speco, all located on the eastern wall, the one closest both to the monks who came from the coenoby rooms (who therefore arrived by ascending) and to the pilgrims who instead descended into the crypt from the upper level. The sequence continued with the episodes of Saint Roman bringing food to Benedict, The Evil One breaking the bell, and theApparition of Christ to the presbytery. On the same wall here is the Temptation of the Evil One in the form of a blackbird and, going down some steps, the Temptation and the Bodily Mortification of the saint, now hidden. The eastern wall of the lower bay contains the Miracle of the Sickle and the Saving of Saint Placidus, while the southern wall houses the two scenes of the Attempted Poisoning of Saint Benedict. It ends with the Death of Benedict and the Vision of the Street of Tapestries, in an inconsistent position, but linked to the desire to place these important frescoes in front of the Speco, as suggested by Roberta Cerone. In the context of this reinterpretation, the clipei with the Blessing Christ and St. Benedict also acquire meaning: the former welcomed devotees coming from the Holy Staircase, while the latter, Caramico explains, “is believed to be functional to support the directionality of the paths that began in the northern bays, and to visually direct monks and pilgrims toward the devotional focus of the complex.”

The third chapter is devoted to the church. Having again clarified the architectural events of this part of the sanctuary, the major novelty concerns the recovery of the usage scenario of the opisthographic dossal assigned to an anonymous Master of the d ossal of Subiaco (hitherto known as the “Master of the dossals of Subiaco,” plural, because it was believed that the two panels, correctly identified as part of the same opisthographic dossal, were actually two separate works). The panels were found in 1947, in a room far from the one where the dossal was originally placed: to understand the intended use of the work, Caramico introduced a comparison between the Subiaco dossal and the two panels by Meo da Siena now in the Städel Museum in Frankfurt, but originally also parts of a single dossal, executed in 1333 and intended for the high altar of the church of San Pietro in Perugia. A work similar in structure, style and size to the Speco dossal, Meo da Siena’s dossal was painted on both sides because of its location in the monks’ choir within the church’s apse: the dossal, in essence, was to be seen by both the faithful and the monks occupying the choir. The derivation of the Subiaco dossal from that of Meo da Siena determines the post quem for the former (1333) and makes it possible to imagine a similar context of use (and consequently to imagine that the fourteenth-century monastic choir of the church of the Sacro Speco was located in the southern bay: an entire chapter is devoted to this problem). In addition, the iconographic analysis of the work finally allowed Caramico to understand where the dossal should originally have been placed, and thus where in ancient times the 14th-century high altar should have been located before the remodeling, namely near the access to the sacristy. Starting from the considerations of scholar Dillian Gordon, the only one to have posed the problem, Caramico has in fact put the figures of the dossal in dialogue with those frescoed in the church, arriving at the deduction that the dossal “would have been exposed, as a sort of hagiographic summa of the sacred figures of the sanctuary, to the vision of the faithful who came to the church at the end of their anabasis through the spaces of the crypt.”

The conclusion of the volume is for the fresco cycles of the 14th century, a moment of great vitality for the sanctuary of Subiaco. The fourteenth-century frescoes also confirm the two directions in which the sanctuary was visited in ancient times, beginning with the two with the Triumph of Death and theMeeting of the Three Living and the Three Dead (works from the workshop of the Master of the dossal of Subiaco), which “introduce with effective vis rhetoric the ascending penitential journey of the laity along the Holy Staircase and, at the same time, the exit of those who had entered the complex through the eastern gate: it is therefore clear and extremely suggestive the function entrusted to the paintings as an eschatological summation of the iconopoiesis of the crypt.” Tied to these images are the Stories of the Virgin (by the Master of the Montelabate dossals) in the chapel of the Madonna, whose images act as a counterpoint to the macabre scenes of the Holy Staircase, muffling their message and reconnecting “to the themes of salvatio animae that run undercurrently through the iconographic apparatus of the crypt.” The cycle of Passion Stories, which is difficult to read as some scenes have not survived, is then considered. Caramico’s analysis ends with punctual stylistic comparisons between the cycles of Subiaco and those of Assisi, from which they derive (so much so that the chapter is entitled “Umbria in the Aniene Valley”): thus, if the Stories of the Virgin’s Infancy look to Giotto models, the Stories of the Passion of the choir “press on following the Lorenzettian thread of the left transept of the lower basilica of Assisi.” Finally, a final section is reserved for the Umbrian origins of the activity of the Master of the Subiaco dossal, whose work is read in the light of what was happening in and around Perugia in the early 14th century.

Virginia Caramico’s book, published in the series Callida Iunctura directed by Andrea De Marchi, stands as a detailed and authoritative essay that rereads in detail two centuries of the events of the sanctuary of the Sacro Speco, proposing, as we have seen, numerous novelties, and advancing reconstructions of great interest, the result of in-depth studies and fine analyses. It should be emphasized how, for De Marchi, Caramico’s work is inscribed “in a very current and promising strand of studies, aimed at an understanding of the relationships of the wall decorations in relation to the spaces they qualify kinetically, in order to reconstruct the paths and viewpoints, beyond the deviant filter imposed by restorations and tampering over the centuries.” It could be the basis for an immersive digital reconstruction, De Marchi notes, to restore to us contemporaries the image of how the Benedictine sanctuary must have presented itself to the eyes of those who entered it in the Two and Fourteenth centuries. A reconstruction that would not be possible without Virginia Caramico’s work.

|

| A book traces the events of the Sacred Speco of Subiaco between the two and fourteenth centuries |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.