A book to reconstruct the story of the important Piccinelli collection, which was dispersed in the 1900s

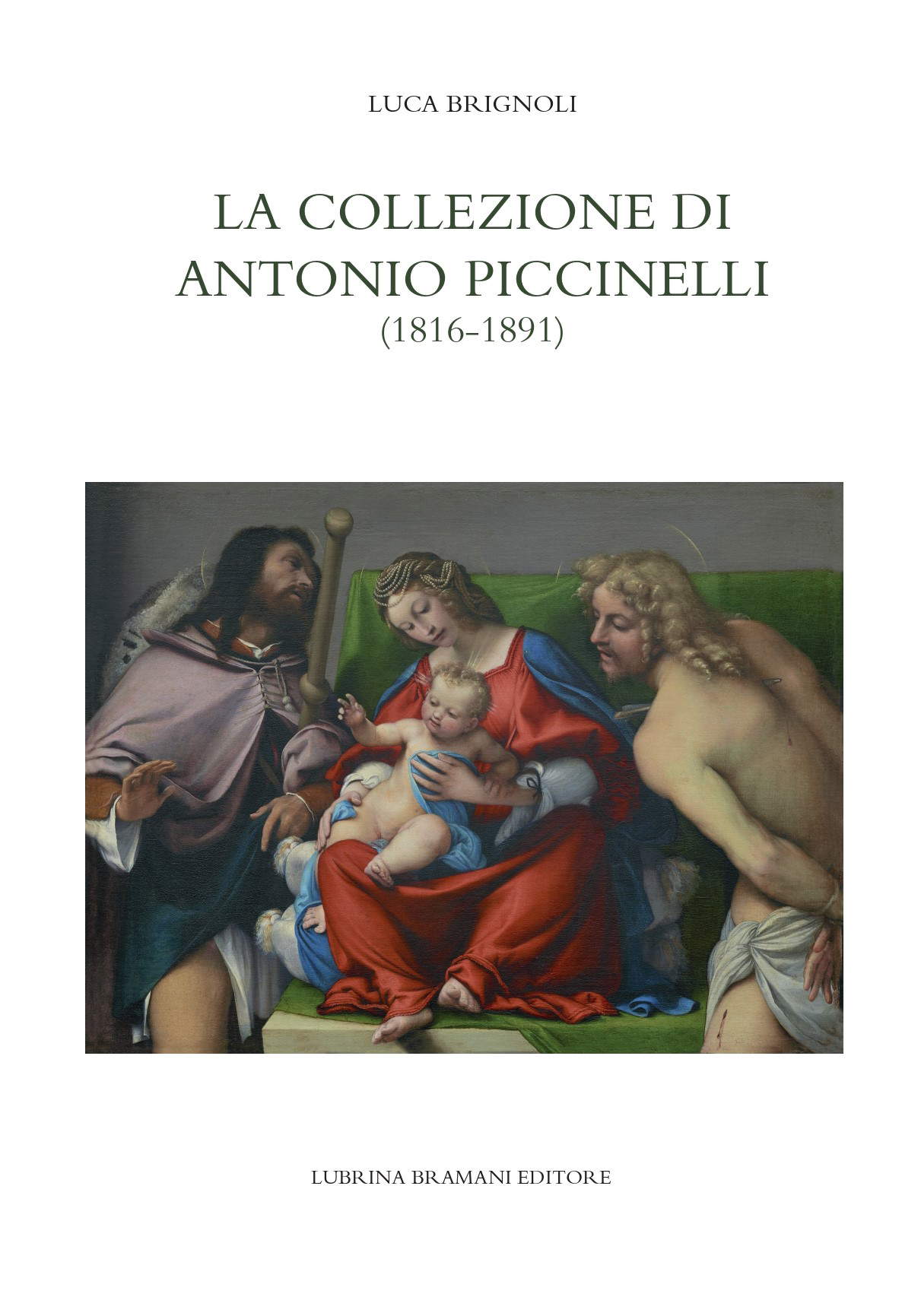

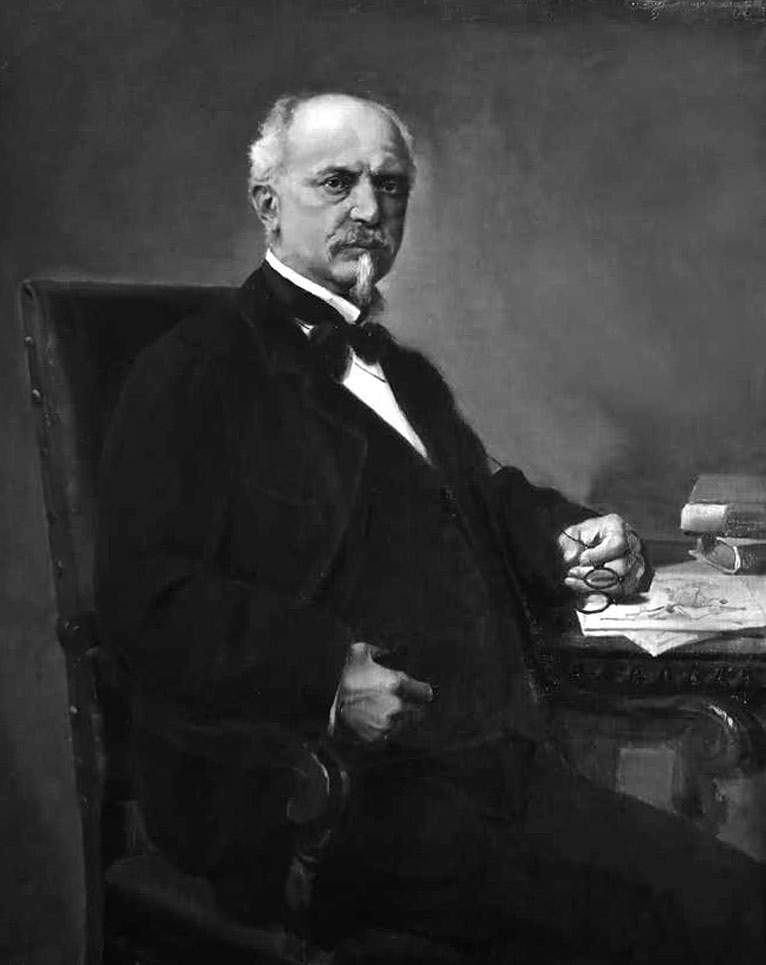

A book dedicated to one of Lombardy’s greatest collectors of the 19th century, the gentleman from Bergamo Antonio Piccinelli (Seriate, 1816 - 1891): this is La collezione di Antonio Piccinelli, a work by young art historian Luca Brignoli published by Lubrina Bramani Editore (444 pages, 90 euros, ISBN 9788877667694). The book weaves the vicissitudes of the collector and his family within the cultural context of Lombardy, restoring to scholars, for the first time in a complete way, a character hitherto not sufficiently considered in the art-historical panorama of the time. Piccinelli gathered in the family villa in Seriate, near Bergamo, a sumptuous collection of about two hundred and fifty paintings, orienting his choices mainly on works from Bergamo and Veneto from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century. Prominent among the most distinguished artists in the Piccinelli gallery are Antonio Maria da Carpi, Gerolamo da Treviso il Vecchio, Giovanni Cariani, Alessandro Magnasco, Evaristo Baschenis, Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, Giacomo Quarenghi, Enea Salmeggia, Giovanni Migliara, and Giovanni Ambrogio Bevilacqua, with theculmination of two paintings by Lorenzo Lotto and a very select series by Giovanni Battista Moroni (Piccinelli narrowly missed buying the famous Sarto on a trip to Venice in 1845) and Fra’ Galgario. The volume (opened by Enrico De Pascale’s preface) reproduces the collector’s main manuscript documents, first and foremost the zibaldone, which inventoried most of the purchases he made, and the postilles to Francesco Maria Tassi’s Lives, a series of illustrative plates, documents, and the complete catalog of the collection.

“Piccinelli’s taste for the artists he collected might seem, at first glance, to be a local choice given by the simple practicality of finding, almost topographically, works of the native school,” Brignoli writes in the introduction to the volume, which stems from his dissertation discussed with Giovanni Agosti. "The choice to compose a collection played largely on Lombard, Venetian and Emilian paintings seems to refer instead to the expression of the ’vero di Lombardia’ contained in the Considerazioni sulla pittura by the Sienese physician Giulio Mancini, where the boundaries of ’Lombardy’ are not limited to those of the present region, but gather all those schools above the Tuscan Apennines: the Po Valley area that, three centuries later, would be so dear to Roberto Longhi. The artists collected by Piccinelli under the Emilian area can be counted on the fingers of two hands; foreign ones (such as the Borgognone of the battles) are frequent names in the empyrean of Orobic collecting. Scrolling through the works in the collection, one realizes how, even numerically, the gentleman’s greatest artistic predilections are represented by Moroni and Fra’ Galgario. [...] To Antonio Piccinelli, who died a bachelor on October 4, 1891, touched an existence devoid of progeny, and certainly, in his shy and collected character, the love for the collected paintings and for art in general represented not only a pastime, but the meaning of a life."

Antonio Piccinelli stood in his time as the latest in a long list of famous Bergamasque collectors (such as Giacomo Carrara, Guglielmo Lochis and Giovanni Morelli): scion of an illustrious family of Seriate, of a closed and introverted character, by trade he was an administrator of goods and estates, but the real passion of his existence was precisely the activity of collecting. He began acquiring works in the mid-19th century and devoted himself to it until a few years before his death. To study and educate himself he traveled extensively: he visited major European museums, even went to North Africa, and exercised a not inconsiderable activity as an art writer. His collecting activity lasted more than 30 years, and there were more than 250 objects he owned, including paintings, sculptures, drawings and engravings. The collection was displayed in the house in Bergamo and especially in the villa, which still exists today, in the center of Seriate. Today we know the arrangement of the paintings in the rooms of the villa thanks to the drawings of his nephew Giovanni Piccinelli. The works in the Piccinelli collection covered a time span of four centuries, from the 15th century to the 19th century, thus including paintings from the Renaissance to Romanticism.

Moreover, the Piccinelli collection was visited by the leading art connoisseurs of the time: Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle was in Seriate between 1864 and 1868, saw some of Antonio Piccinelli’s paintings and noted them in his notes now kept at the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana in Venice (among them, St. Jerome in the Desert by Gerolamo da Treviso the Elder, the panel with the Four Saints at theat the time given to Romanino and today instead assigned to an unknown artist of his circle, the Madonna and Child by Antonio Maria da Carpi, St. Jerome in the Desert by the workshop of Cima da Conegliano, theAngel with Globe and Scepter and the Madonna and Child and Saints Roch and Sebastian by Lorenzo Lotto, and the Flight into Egypt by Giovanni Cariani). Bernard Berenson visited the gallery after Piccinelli’s death in 1891, also noting some works on his Notes Places. Another distinguished visitor was the aforementioned Giovanni Morelli.

Luca Brignoli’s book also traces the stages of the genesis of the collection, in a special chapter. The pivotal year is 1859, when the collection did not yet include any of the most celebrated masterpieces: this was the year Piccinelli had the opportunity to acquire a dozen important paintings, including theAdoring Angel, which Piccinelli attributed to Giovan Battista Moroni but which later flowed into Moretto’s catalog. “The Angel,” Brignoli explains, “paved the way for a conspicuous fortune for Moroni at the Piccinelli collection: in fact, it was the first of eight paintings by this artist to reach the banks of the Serio River.” The leap forward, however, came in 1862, when the role of consultant to Giuseppe Fumagalli intensified, who was a painter, antiquarian and restorer, as well as a friend of Antonio Piccinelli, and his prompter in the acquisition of many paintings, as well as his companion during some trips. That year, Piccinelli purchased Giovanni Cariani’s Flight into Egypt, a Madonna and Child by Antonio Maria da Carpi, and then again a sketch by Giovan Battista Tiepolo depicting the Madonna and Child with Saints Francis, Anthony of Padua, and Dominic. The highlight, however, would come in 1864, with Lorenzo Lotto’s Madonna and Child with Saints Rocco and Sebastian, the best item in the collection: “This,” he would write in his zibaldone, “is one of L. Lotto’s best easel paintings, certainly superior to the one extolled at the Accademia Carrara and the others from the house of Lochis and Camozzi formerly Pezzoli.” Brignoli’s book details the occasions during which Piccinelli acquired the best pieces in his collection.

The death, on October 4, 1891, of Antonio Piccinelli was the beginning of the end of the collection. The works passed entirely to his only nephew, Giovanni, son of his brother Ercole (Antonio in fact died unmarried and childless). Giovanni was a refined and cultured person who, however, had interests other than those of his uncle, and as early as 1895 he began to sell some of the works in the family collection. These included the Madonna and Child by Antonio Maria da Carpi, which was sold to Brescian antiquarian Achille Glisenti, who in turn sold it to the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest, which that same year managed to procure, again through antiquarians to whom Giovanni Piccinelli had sold his uncle’s works, three more pieces from the collection. However, the bulk of the collection was kept by Giovanni. Later, after the 1909 Rosadi Law (one of the first laws on protection), the superintendent of Milan, Ettore Modigliani, bound some of the works in the collection, including Lotto’s Madonna, Cariani’s Flight into Egypt, the Four Saints then attributed to Romanino, the Martyrdom of St. Theodora and Tiepolo’s Madonna and Child with Saints.

In 1913, after Giovanni’s death, the collection passed to the latter’s son, Ercole Piccinelli, who was most responsible for the collection’s diaspora, which he neglected to the point that in some cases, Brignoli explains, the works were sold at cut-rate prices. “To him,” the aide writes, “we also owe some alienations of already bound paintings (Lotto, Tiepolo, Fra’ Galgario), however, in the will there are more than two hundred works mentioned and bequeathed to the grandchildren, testifying that, in spite of everything, the amount of art objects in the family’s possession was still conspicuous. It was precisely during the years of World War I that a number of alienations took place in favor of private individuals and speculative merchants such as Augusto Lurati, who got his hands on paintings by Moroni and Tiepolo, until he got to the most coveted piece: the sacred composition by Lotto.” Lotto’s masterpiece was the subject of a failed negotiation to bring it into the national public collections: It then went to a private collector and flowed, in the 1950s, into the Contini Bonacossi Collection, and it is one of the works that, following the controversial ad hoc law to manage the sumptuous Florentine collection, took the road abroad (Parliament, in order to resolve conflicts over the inheritance Contini Bonacossi, had passed a law that gave the green light to most of the works in the collection, in exchange for the possibility of retaining those that a commission of experts would judge to be the masterpieces that Italy should secure for public collections: the Lotto unfortunately was not among them).

However, Brignoli writes, “The blackest parenthesis of the collection occurred [...] when Antonia Piccinelli [Ercole’s sister, ed.] married General Giacomo Siffredi in second marriage. The latter, a dishonest and businesslike person, sold, convincing Hercules [...], some paintings with false attributions, in order to make more money. The greatest snub, however, dates back to the death of his wife, when Siffredi received in usufruct some property owned by his spouse and, contrary to his powers, appropriated some paintings (and perhaps even sold them). Antonio Piccinelli’s zibaldone was one of the possessions that the general took possession of, and that is why it went missing along with some of the paintings.” Today, many of the paintings that once belonged to Antonio Piccinelli can be found in the world’s most prestigious museums (from the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest to the Eskenazi Museum of Art at Indiana University, from the Pinacoteca di Brera to the Accademia Carrara in Bergamo, from the National Gallery in Ottawa, where Lorenzo Lotto’s Madonna is located, to the Museums of Castello Sforzesco), and in numerous private collections, while others have taken unknown destinations (the two paintings by Tiepolo, for example: their whereabouts are currently unknown), but the collection has unfortunately gone missing. “The fate that befell many Piccinelli works scattered today in museums halfway around the world, from Milan to Budapest, from England to overseas institutions such as the United States and Canada,” Brignoli concludes, “reminds us of the ephemeral and extremely delicate fate to which art collections are subjected. The Seriate collection represents only one of the many once widespread throughout the Peninsula, and more famous and impressive events such as those related to the Barberini or Contini Bonacossi collections should be considered real ’stone guests’ with respect to the management of Italy’s artistic heritage, which has always been exposed to more or less licit exports, despite pioneering legislative measures of protection. Protecting and preserving Italy’s artistic heritage means, in the groove traced by Article 9 of the Constitution, honoring the Nation. Collecting works of art is not just an elitist operation through which to demonstrate one’s status and relative economic power, an act of snobbish privatization. If done intelligently, this activity can become a true vocation, because truly (in the words that came out of Walter Benjamin’s pen) ’for the collector, in each of his objects is present the world itself.’”

The book is rounded out with a cultural profile of Antonio Piccinelli, a transcription of the zibaldone where Antonio Piccinelli’s purchases were noted, one of his writings (Piccinelli’s postilles to the Lives of Francesco Maria Tassi), and, of course, the complete catalog of the works (each of which has a card with an exhaustive description, history of provenance, current location and technical data), and a very rich illustrative apparatus. A volume that therefore, thanks to Luca Brignoli’s excellent work, restores to Antonio Piccinelli a place of honor in the vicissitudes of Bergamasque and Lombard collecting, placing him as the continuer of a tradition that had seen in Carrara and Lochis the best exponents. Leafing through the pages of the book one realizes how valuable Piccinelli’s collection was and the heritage that was lost with its diaspora.

|

| A book to reconstruct the story of the important Piccinelli collection, which was dispersed in the 1900s |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.