"Valençay's man? He is not Machiavelli, and the work is not by Leonardo." Scholar Stéphane Toussaint speaks.

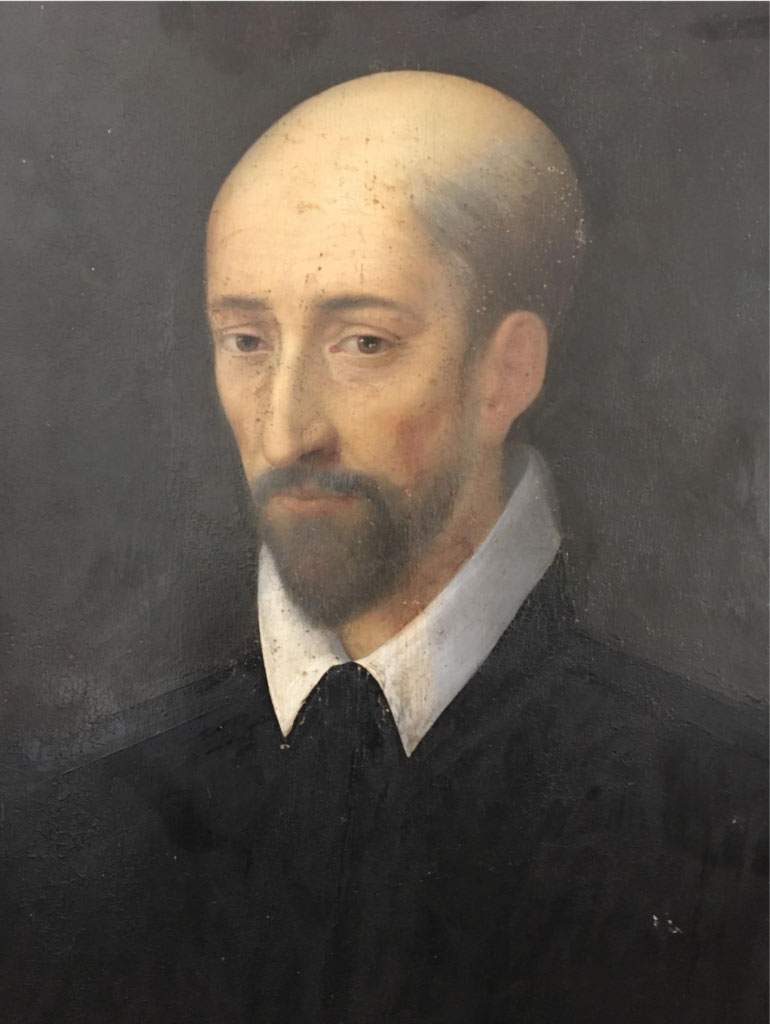

Concerning the alleged portrait of Niccolo Machiavelli assigned to Leonardo da Vinci and for which, a few days ago, we provided some elements to discard such a lofty attribution, we are alerted to an interesting article published in La Tribune de l’Art and written by Stéphane Toussaint, CNRS (the French counterpart of our CNR) research director at the Centre André Chastel of the Sorbonne University: the piece dryly rejects the name of Leonardo da Vinci for the work found at Valençay Castle, and also denies the identification of the subject with the Florentine philosopher.

“The explicit attribution to Leonardo,” Toussaint explains, "goes back to precisely October 24, 1874, when Léon Chevrier shipped the work to Paris. Who was Chevrier? An art historian, a connaisseur? Not at all: the château’s secretary-treasurer. Before him, the attribution of the portrait to Leonardo was but a vague fantasy. In her study, Anne Gérardot [editor’s note: a functionary of the departmental archives of l’Indre, the French department where Valençay town is located] suggests that it is not a Leonardesque work, but a copy from the 19th century."

What’s more, Toussaint also explains why the work does not depict Machiavelli either: “the bearded pseudo-Machiavelli,” he writes, “displays a hairiness highly unlikely for the glabrous Florentine Secretary. If my recollections are correct, the only occurrence of a bearded Machiavelli towers over the frontispiece of the edition of the complete works published by Poggiali in Livorno in 1796.” A bearded Machiavelli who, Toussaint adds, in 1799 caused Gaetano Cambiagi, Poggiali’s rival, to marvel: “summa was the surprise of seeing an entirely new and unknown physiognomy appear,” Cambiagi wrote in the 1799 edition of Machiavelli’s complete works, "with a beard on his face, and with a Spanish-style habit, which in those times was not used per avventura in any part of Italy, and in no way in Florence. How many portraits have been made of Machiavelli, excluding only this one in the Livorno edition with the date of Philadelphia, all depict him quite differently, with a shaved beard, and in the ceremonial garb used by the public officials of the Florentine Republic. It was, however, easy for that editor to observe him with such a robe on and beardless as far as the frontispieces of the Edition of the Testine, and similarly beardless in the medallion of the Mausoleum modernly erected to him, of which he himself, after the example of our edition, has given the representation in copper. Now, the portrait of Niccolò, as we have given it, and as the compiler of the collection of illustrious Florentine men had given it before, is taken from the very well-known originals existing at the Ricci family in Florence, one by Santi di Tito, and the other by Bronzino, and these correspond perfectly with the life-size terra cotta bust, which also from the same Ricci family is possessed, or which is made on the mask hollowed out of Machiavelli’s own face after his death."

|

| Florentine artist, Niccolò Machiavelli (16th century; polychrome terracotta, life-size; Florence, Palazzo Vecchio) |

|

| François Quesnel, Portrait of Montaigne (c. 1588; pencil and black stone, 33.5 x 23 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Raffaello Morghen, Niccolo Machiavelli (1796; engraving, 13 x 10 cm; Livorno edition of 1796). Ph. Credit Gino Bogliolo |

The Poggiali edition reproduces, Toussaint points out, an engraving drawn by Georg von Dillis in 1794 and printed by Morghen in 1795, itself derived from an unidentified work by Bronzino or his school (although it is doubtful that this painting really depicted Machiavelli). The terracotta mentioned by Cambiagi, however, is now in Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio. The character depicted by Dillis, Toussaint hypothesizes, “closely resembles Montaigne, a thinker traditionally effigyed with a beard, as attested by portraits, drawings and his cenotaph in Bordeaux. [...] And the bearded pseudo-Machiavelli of Valençay evokes an aged Montaigne. This is also what Anne Gérardot noted about the subject of the painting.” Valençay’s work, Toussaint concludes, “resembles Machiavelli infinitely less than Montaigne, and the character is painted in a pose that essentially recalls a sketch by François Quesnel.”

Toussaint also does not spare a lunge against the fashion of launching fanciful attributions if a great artist like Leonardo da Vinci is involved: “Today in France, the name of Leonardo da Vinci sells anything,” notes Centre director André Chastel, “So much the worse for the public, abused through continuous media affabulations. Selling has become the only ontological proof of our society: I sell, therefore I am. Everything else (erudition, research, truth) arouses little interest. And in this exercise, the media usually merely observe a false modesty: the use of a small conditional that promises everything but affirms nothing. It is up to you to believe it. In the cultural commodification of our beautiful ”knowledge economy,“ falsification is allowed, and as Deleuze already observed about our media intellectuals, it matters little for their absence of ideas or the vacuity of their books, if around this absence and emptiness the marketing works wonders.”

Image: Unknown 16th-century artist, Portrait of a Gentleman (16th century; oil on panel, 55 x 42 cm; Valençay, Valençay Castle)

|

| "Valençay's man? He is not Machiavelli, and the work is not by Leonardo." Scholar Stéphane Toussaint speaks. |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.