Munch's Scream is becoming discolored. A team led by Italian researchers finds the problem and proposes solution

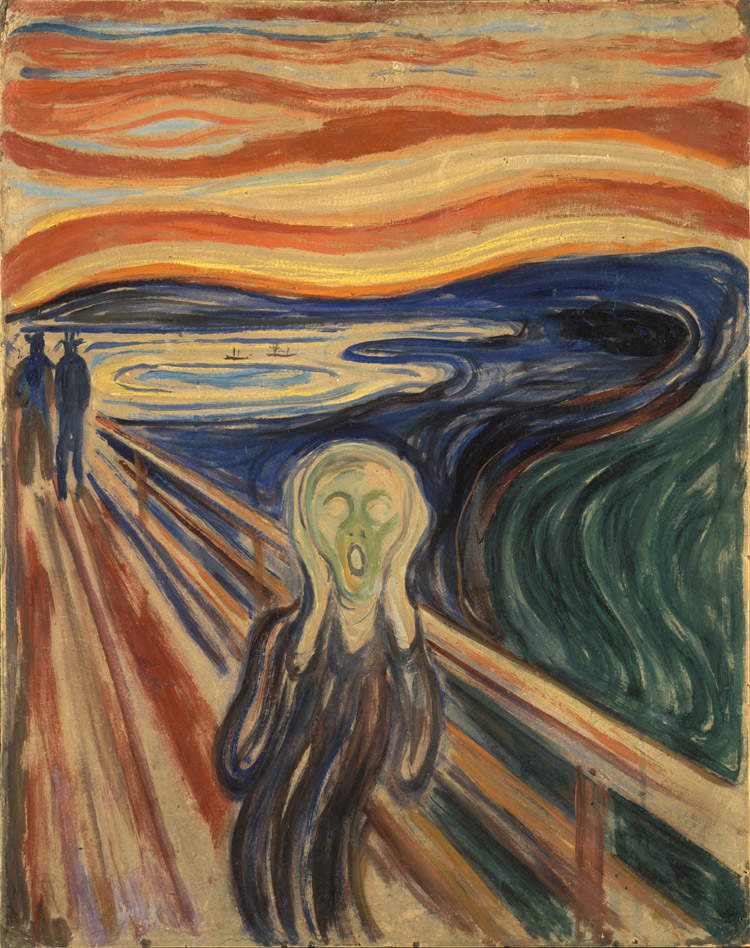

It is one of the masterpieces of world art history: theScream by Norwegian painter Edvard Munch (Løten, 1863 Oslo, 1944), painted in several versions starting in 1893, is a painting that has become a symbol of an era. A symbol, however, that does not enjoy good health: the 1910 version (the last one), kept at the Munchmuseet in Oslo and the most important work of the institution in Norway’s capital city, has been exhibited to the public infrequently since 2006, due to its delicate condition, partly due to the action of external agents, partly due to the damage suffered by the cartoon during the 2004 theft (it took two years to get it back to the museum), and partly due to the pigments used by Munch.

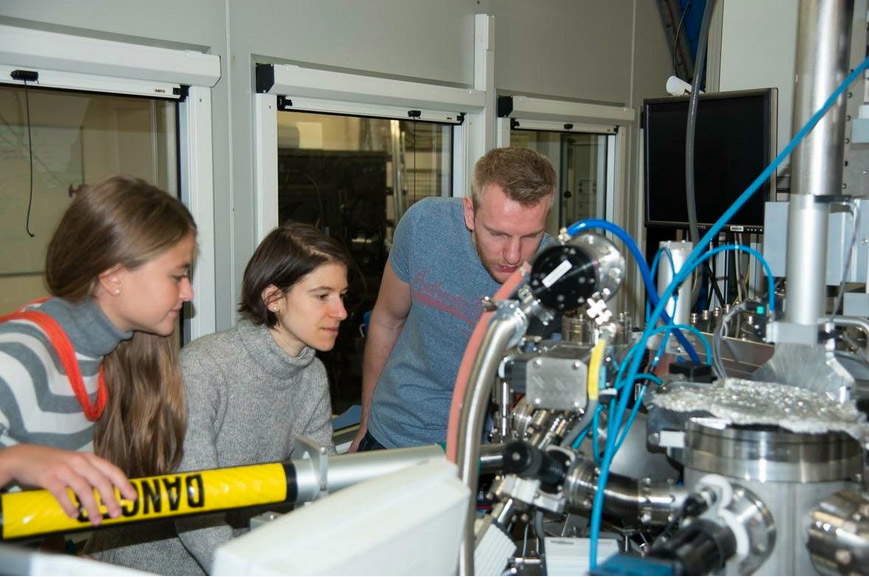

The fact remains that Munch’s masterpiece is becoming discolored. The work has been subjected to careful analysis by an internationalteam, coordinated by an almost all-femaleteam of Italian researchers from the National Research Council (CNR). The research team studied the painting at the Munchmuseet with the help of portable instrumentation, based on non-invasive spectroscopy methods, from the European Molab platform (funded by the European Commission in the context of the Iperion-Ch project), a mobile laboratory coordinated by Costanza Miliani, director of the Institute of Cultural Heritage Sciences (Ispc) of the CNR. In a second step, experiments with X-ray sources were carried out at the European synchrotron radiation facility (ESRF, Grenoble, France) on micro-fragments taken from the work. The study was published in the scientific journal Science Advances, in an article signed by Letizia Monico, Laura Cartechini, Franesca Rosi, Annalisa Chieli, Chiara Grazia, Aldo Romani, Costanza Miliani and Renato Pereira de Freitas of CNR, Steven De Meyer, Gert Nuyts, Frederik Vanmeert and Koen Janssens of the AXES research group at the University of Antwerp (Belgium), Marine Cotte and Wout De Nolf of the ESRF, Gerald Falkenberg of DESY in Hamburg, Irina Crica Anca Sandu and Eva Storevik Tveit of the Munchmuseet, and Jennifer Mass of the Bard Graduate Center in New York.

|

| Edvard Munch, LUrlo (1910; tempera on panel, 83 x 66 cm; Oslo, Munchmuseet) |

|

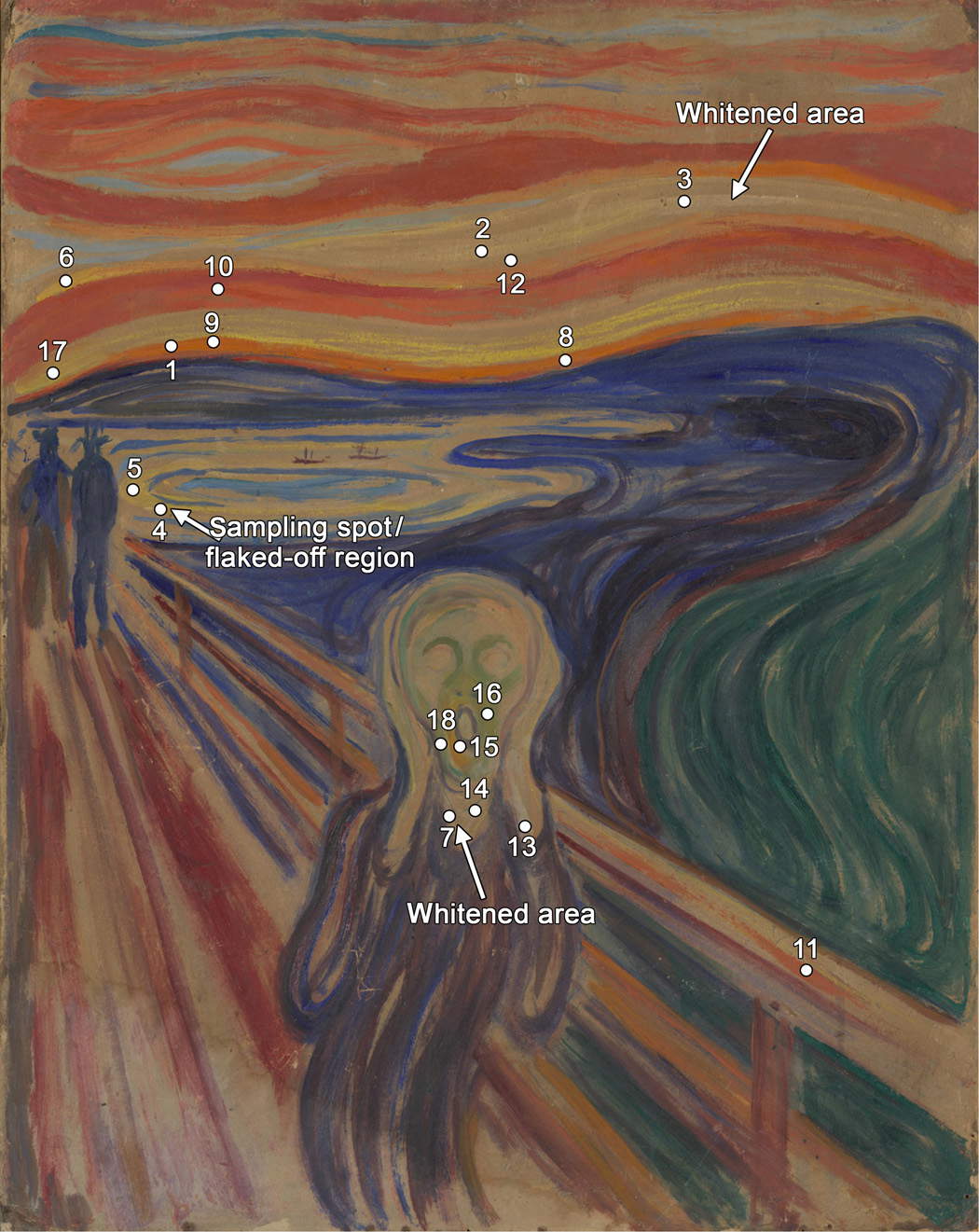

| The painting’s problems: discoloration (whitening) and flaking (flaking). |

The signs of the painting’s deterioration, the scholarly paper states, are seen mainly in the clouds of the setting sky and the neck of the screaming figure, painted with cadmium yellow, which in recent years has undergone a process of losing its original color, turning to white. The same applies to the waters of the lake, another area where Munch had applied several brushstrokes of cadmium yellow. Evidence of these problems emerged in 2006: for these reasons the work had been removed from public view (and exhibited only rarely), to be placed in storage in an environment maintained under controlled conditions of light, temperature (18 degrees) and humidity (50 percent). Cadmium yellow is a pigment widely used at the time; it is also found in works by Matisse, van Gogh, and Ensor, and discoloration, flaking, and degradation of the paint film have been documented for all these artists.

“Lartista,” explains Letizia Monico, a researcher at the CNR’s Institute of Chemical Sciences and Technologies “Giulio Natta” in Perugia, Italy, “mixed different binders, such as tempera, oil and pastel with synthetic pigments with vibrant and brilliant tones to create striking colors. Unfortunately, the extensive use of these new materials poses a challenge for the long-term preservation of the Norwegian painter’s artworks.” Indeed, the 1910 version “shows obvious signs of decay in several areas painted with cadmium yellows, a family of pigments consisting of cadmium sulfide. The original bright yellow color of some of the clouds in the sky and the neck of the central subject appears faded today. In the lake area, the dense, opaque brushstrokes of cadmium yellow instead show a tendency to flake off.” Given this evidence, the researchers wondered if there are correlations between the painting’s degradation and the chemical composition of its colors, what is the nature of the cadmium yellow alteration, and what environmental factors contribute to accelerating this process.

Analysis by the CNR-led team found that it ismoisture that is one of the main causes of cadmium yellow pigment degradation. “The study of the painting,” Monico further points out, “was supplemented with investigations of artificially aged laboratory pictorial specimens, prepared using a historical powder and an oil tube of cadmium yellow that belonged to Munch, having a chemical composition similar to the yellow pigment in the painting’s lake. The study shows that the original cadmium sulfide transforms into cadmium sulfate in the presence of chlorine-containing compounds and under conditions of high percentage relative humidity; this happens even in the absence of light.” In short: the problem is caused by the chemical composition of the pigment, which reacts in high humidity situations.

In its conclusions, the CNR-led research also provides the possible solution: “We believe,” the researchers write, "that our findings provide important clues to the mechanism of degradation of cadmium sulfide-based paintings, and this has important implications for the preventive conservation of theScream of c. 1910. In particular, the degradation of cadmium yellow could be mitigated by minimizing the exposure of the painting in excessively high humidity conditions (not exceeding 45 percent) and by maintaining illumination at the normal values expected for light-stable painting materials," which includes cadmium yellow. Finally, the study introduced a novelty with theintegration of different investigative techniques: this approach, the researchers suggest, may be successfully used to examine other works of art suffering from similar problems.

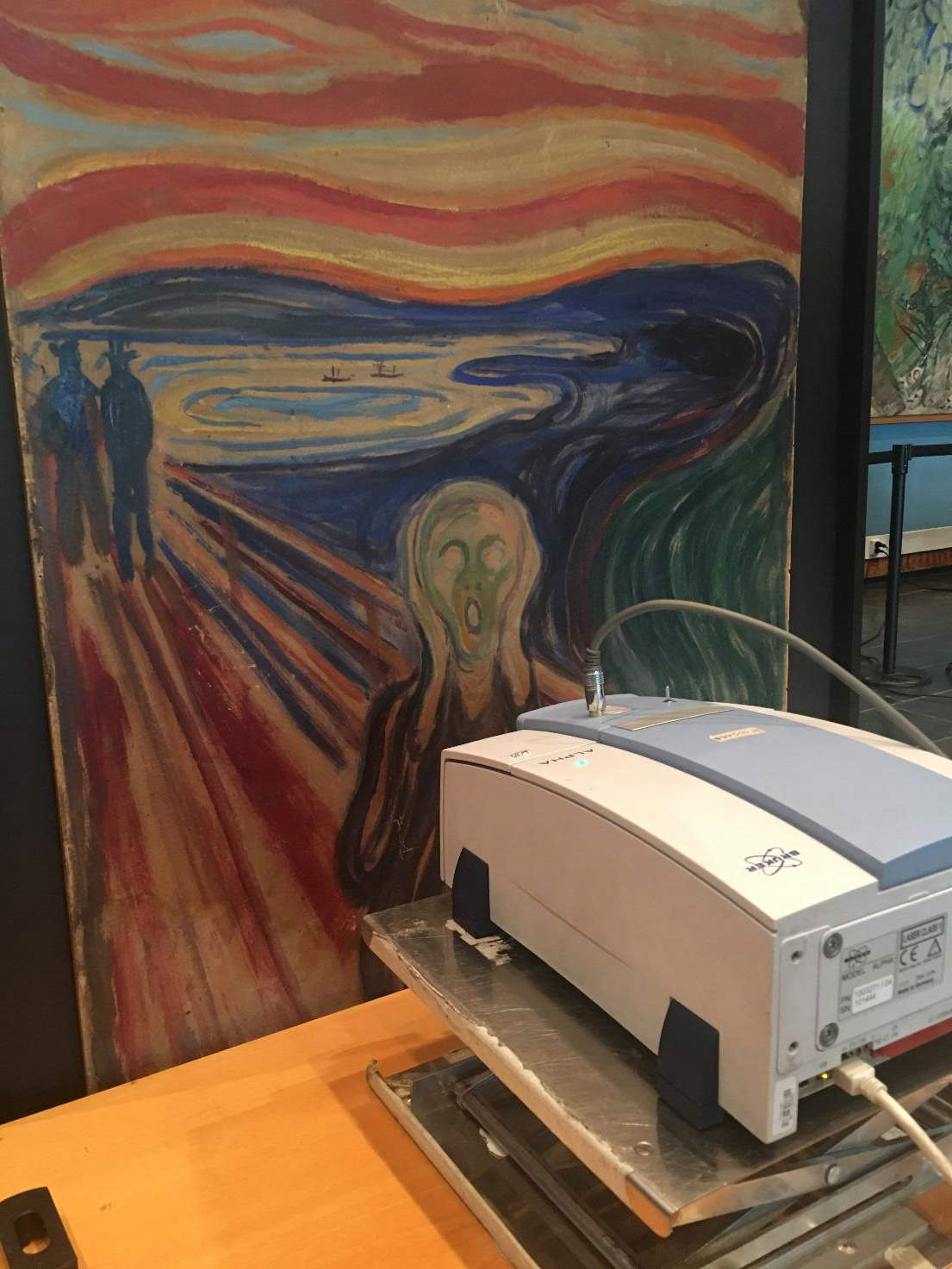

Below are some images of the study operations.

|

| Portable UV-Visible fluorescence spectrophotometer employed during the MOLAB access performed at the Munch Museum in Oslo for the study of LUrlo (1910?). Ph. Credit SMAArt Center of Excellence, University of Perugia |

|

| UV-Visible fluorescence imaging analysis of de LUrlo (1910?), aimed at the identification of different types of cadmium yellows. Ph. Credit CNR Molab, SMAArt Center of Excellence, University of Perugia. |

|

| Portable instrumentation for non-invasive infrared spectroscopy analysis while performing investigations on LUrlo (1910?). Ph. Credit MOLAB (CNR-SCITEC, Italy) |

|

| Left to right: Francesca Rosi, Costanza Miliani and Laura Cartechini while performing noninvasive infrared spectroscopy analysis with portable instrumentation on the work. Ph. Credit MOLAB (CNR-SCITEC, Italy) |

|

| Letizia Monico and Francesca Rosi while performing noninvasive infrared spectroscopy analysis with portable instrumentation on The Scream. Ph. Credit MOLAB (CNR-SCITEC, Italy) |

|

| Pictorial specimens prepared in the laboratory and artificially aged. Ph. Credit CNR-Scitec |

|

| A moment of the investigations at lESRF European synchrotron radiation facility, Grenoble, France. Ph. Credit ESRF |

|

| Munch's Scream is becoming discolored. A team led by Italian researchers finds the problem and proposes solution |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.