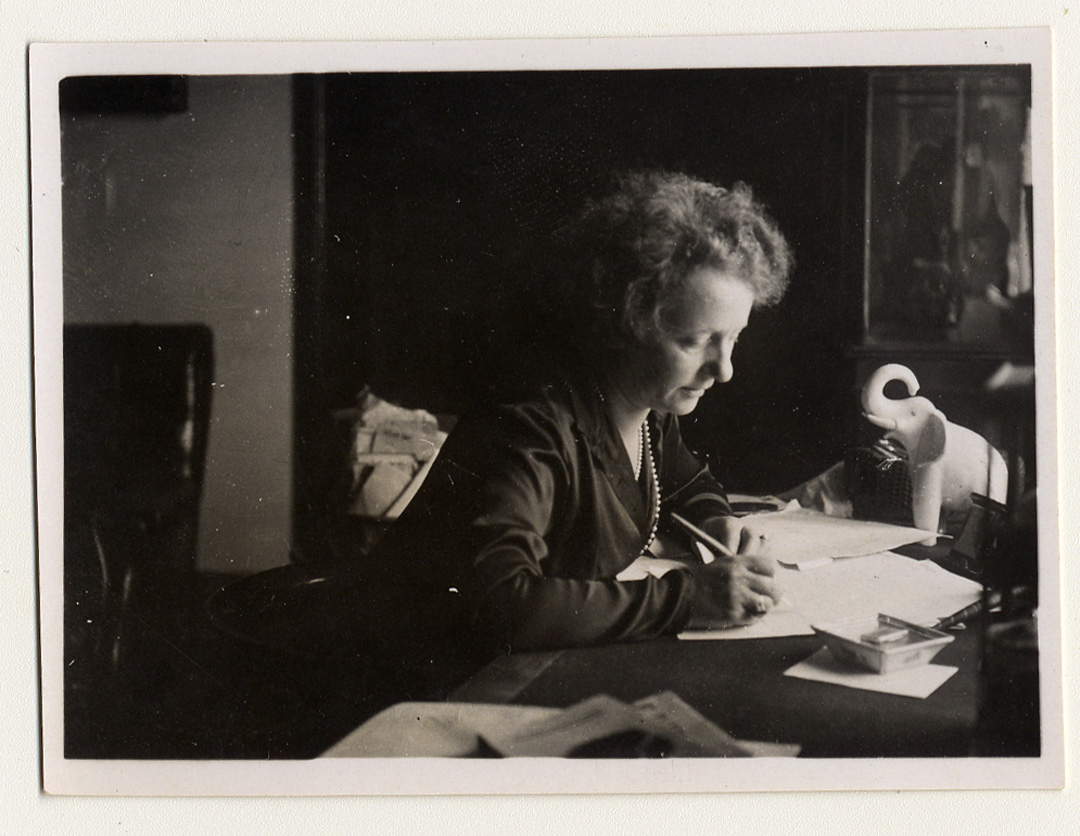

That of Margherita Sarfatti (Margherita Grassini; Venice, 1880 - Cavallasca, 1961) is not a name frequently encountered in school textbooks, yet her influence spanned decades of Italian history, intertwining with the artistic and political currents of the early 20th century. An art critic, journalist, and writer, she was at the center of the Italian cultural scene during the years of Fascism, moving skillfully between the intellectual salons of Milan and the political stage of the Fascist regime. Those who have heard of her without cultivating a particular passion for art will probably know her first and foremost for beingBenito Mussolini’s mistress, but in fact Margherita Sarfatti’s role is central to Italian art of the last century.

It must be premised that her figure has been tarnished precisely because of her association with the Fascist regime (and yet she herself, from a Jewish family, ended up being affected by the racial laws of 1938): nevertheless, despite her undeniable complicity, Margherita Sarfatti has long been the subject of a relocation within the art-historical literature and art of her time, culminating between 2018 and 2019 with an important double exhibition that the Museo del Novecento in Milan and the Mart in Rovereto have dedicated to her. So, who was Margherita Sarfatti really? A visionary militant critic? A manipulator? A woman ahead of her time?

Margherita Grassini, later married Sarfatti, was born on April 8, 1880, in Venice, in a wealthy Jewish family, the last of four siblings. Her father Laudadio Amedeo was a successful lawyer and entrepreneur, while her mother, Emma Levi, came from an equally respectable Venetian family: she was a cousin of Giuseppe Levi, father of writer Natalia Ginzburg. Raised in a cultured and privileged environment, Margherita received a private education that nurtured her passion for literature and art. Among the teachers and intellectuals she was able to associate with as a teenager she had, for example, Antonio Fogazzaro, Antonio Fradeletto, Pietro Orsi, and Pompeo Gherardo Molmenti. However, young Margherita was not content to observe the gilded world in which she lived: she was attracted to socialist ideas, which brought her into conflict with her family’s conservative orientation.

In 1898, when she was only 18, she married Cesare Sarfatti, a Jewish lawyer thirteen years her senior, who shared her socialist political beliefs. The marriage, which was not approved by her father Laudadio Amedeo (the Sarfatti family had a lower social standing than the Grassini family, and there was a wide age difference between the two), marked the beginning of a new phase in her life: the two moved to Milan, the beating heart of cultural and political innovation at the time, and went to live on Via Brera. Three children were to be born of their marriage: in 1900 Roberto Sarfatti, who died at only 18 fighting on the Col d’Echele in World War I; in 1902 Amedeo; and in 1907 Fiammetta.

In Milan, the Sarfatti family quickly became part of the city’s vibrant intellectual environment. Their home became a meeting place for artists, writers and politicians. Margherita, with her brilliant wit and extraordinary oratorical skills, was not just a guest: she was the center of those salons.

Here, in 1902, Margherita Sarfatti began working for L’Avanti!, and in 1909, at the age of twenty-nine, she became the socialist newspaper’s art critic, directing its art page. Also, in 1912, she was among the first socialist contributors to the magazine La difesa delle lavoratrici founded by Anna Kuliscioff that same year. The year 1912 represents an important juncture in Margherita Sarfatti’s life, because that year the art critic met Mussolini, three years younger than her and twenty-nine years old at the time: at the time, the future Duce was already one of the most prominent exponents of the PSI, and he was preparing to become the editor of L’Avanti!

In the following years, Margherita Sarfatti was to become the animator of one of Milan’s most important cultural salons, habitually frequented by literati and journalists (such as Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Aldo Palazzeschi, Mario Missiroli, Massimo Bontempelli, Ada Negri, Sam Benelli) and artists, such as many exponents of the Futurist group (Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo), young people such as Arturo Martini, Mario Sironi, Achille Funi, Marcello Piacentini, and Antonio Sant’Elia, and established artists such as Medardo Rosso.

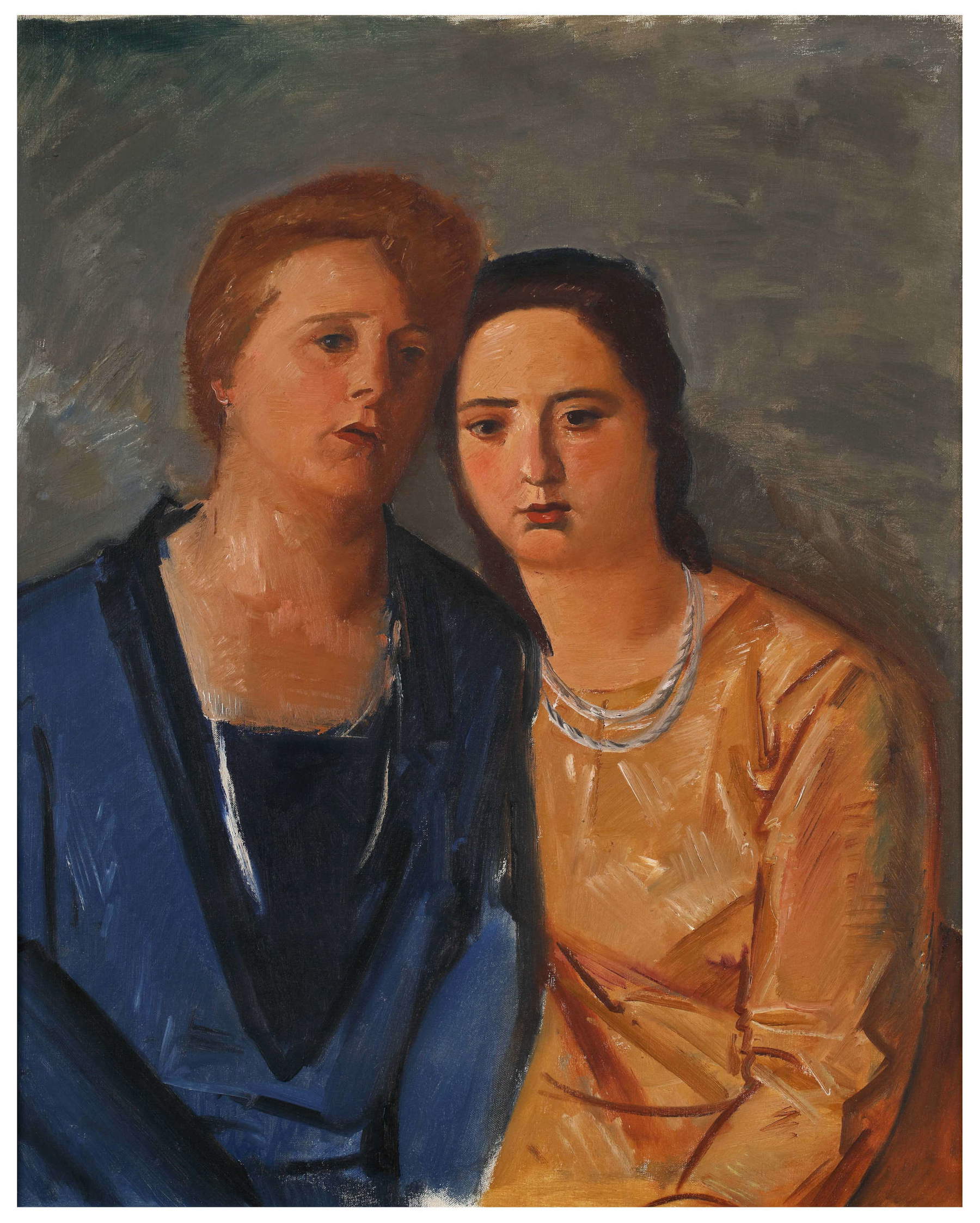

It was in 1922 that he and gallery owner Lino Pesaro founded the Novecento art movement, an avant-garde group that aimed to renew Italian art by drawing inspiration from the classical tradition but preserving a modern language that was both free and simple. The first exhibition was held at Galleria Pesaro in Milan in March 1923 and featured seven artists-Mario Sironi, Achille Funi, Leonardo Dudreville, Anselmo Bucci, Emilio Malerba, Pietro Marussig, and Ubaldo Oppi.

The Novecento movement was not only an artistic expression, but also a cultural project with profound ideological implications. Margherita Sarfatti, with her critical intelligence and ability to network the most promising talents of the time, was its inspiring soul. Artists who recognized themselves in the movement were supported and guided by Sarfatti, who often intervened directly in the selection of their works for exhibitions and galleries. Her ideas on art, based on a vision that integrated modernity and art-historical tradition, also found an international echo. Margherita Sarfatti was therefore not only a promoter of the group, but helped define the aesthetic taste of her time.

Sarfatti would put her artistic ’program’ down on paper in a highly effective text published in the catalog of the 1924 Venice Biennale, which had reserved a room for Novecento painters (reduced in the meantime to six due to the defection of Ubaldo Oppi). “Deities long fled, here now are the general ideas, the master ideas, returning to the domain of the plastic arts”: Sarfatti regarded her artists as deities. “Six young painters, who were among the first to fight for the beautiful eyes of concept and composition, thought of huddling together in a handful to better circumscribe the rights of pure visibility. Thus was born in 1922 in Milan the group that called itself ’del Novecento.’ The name displeased, as if the six had grabbed the century all to themselves, and the name was dropped. The group remained, and its existence is a symptom. Today’s six have realized that they have been fighting elbow-to-elbow for a while. They bring to the art each their own vision but, though in the freedom of individual temperaments and convictions, they tend concordantly toward some essential unity. It is consoling to see that the search itself leads them, as if by the hand, toward clearer and clearer ideals of concreteness and simplicity.”

The art of the Novecento group was never state art, despite the link between Margherita Sarfatti and the regime: it never took on an official imposed or exclusively propagandistic character like other art forms associated with totalitarian regimes (e.g., Socialist Realism in the Soviet Union or the cultural productions of Nazi Germany). Twentieth-century artists did not work under an officially established state-established artistic program: on the contrary, the movement promoted a plurality of voices united by the intent to combine tradition and modernity, leaving room for individual freedom of expression while remaining in tune with the dominant ideology. Fascism, especially in the early years, showed itself open to various artistic currents, including the Novecento, while still exercising control and censorship. However, it never made this movement the only official language of Italian art. Mussolini himself, despite his friendship with Sarfatti, never adopted the Novecento as the regime’s exclusive form of aesthetic representation. Indeed, not everyone in the regime appreciated the Novecento: Mussolini himself, in a letter to Margherita Sarfatti dated July 9, 1929, wrote: “this attempt to make people believe that the artistic position of fascism, is your ’900, is now useless and is a trick ... since you do not yet possess the elementary modesty of not mixing my name as a political man with your artistic inventions or self-styled such, do not be surprised if at the first opportunity and in an explicit way, I will specify to you my position and that of Fascism in the face of the so-called ’900 or what remains of the late ’900.”

One of the most controversial aspects of Margherita Sarfatti’s life was her relationship with Benito Mussolini. The two, as mentioned, met in the early twentieth century, when Mussolini was a young socialist leader and journalist. Margherita was fascinated by him, as much for his ideas as for his charisma. Their relationship, which lasted for more than a decade, was not only sentimental but also intellectual. The future Duce wanted her as a contributor to Il Popolo d’Italia, the newspaper he had founded in 1914, after resigning from the editorship of L’Avanti!, and on which Margherita began writing as early as 1918.

Margherita Sarfatti played a crucial role in Mussolini’s political rise. It was she who introduced him to the circles that helped him build his support network. She was present in Piazza San Sepolcro in Milan when the Fasci italiani di combattimento was founded on March 23, 1919. He also collaborated actively in the regime’s propaganda, writing articles and essays extolling him. The most famous is The Life of Benito Mussolini, published in England in 1925 and then released in Italy the following year under the title Dux, a biography of the dictator, inspired by Giuseppe Prezzolini, which was an extraordinary success (more than one and a half million copies sold in Italy), being translated into many languages. In 1926, Margherita Sarfatti also decided to move to Rome with her children (her husband Cesare had passed away in 1924), to be close to the Duce.

The relationship with Mussolini was not without its shadows. Over time, ideological and personal disagreements led to a gradual estrangement, partly due to friction between Margherita Sarfatti and the regime’sintelligentsia , which did not see her influence on the Duce well: contrary to many party cadres, Margherita Sarfatti would have liked to bring Italy closer to the United States rather than Hitler’s Germany (for this reason, she also traveled to the United States in 1934). The regime’s intellectuals also tried to downplay her role within the Novecento group, which by 1934, after more than ten years of activity, could be said to have disbanded. In 1938, with the introduction of the fascist racial laws, Margherita Sarfatti was no longer safe in Italy (her sister Nella Grassini Errera remained in Italy and was deported with her husband to Auschwitz, where she died), although she had formally abjured Judaism and converted to Catholicism as early as 1928: she therefore had to leave Italy and take refuge first in Paris, then in Uruguay and then in Argentina, where she continued her work as a journalist and cultural animator.

After World War II, in July 1947, Margherita Sarfatti returned to Italy, settling in Rome, but her influence had now faded. Her ties to fascism had made her a controversial figure, and the postwar Italian cultural world was reluctant to recognize her merits. Nevertheless, she continued to write, work as a journalist (she wrote for Il Roma, Scena illustrata and Como) and promote art until her death on October 30, 1961, in Cavallasca, near Como, where she had a villa.

Beyond her political role, Margherita Sarfatti was a central figure in the promotion of twentieth-century Italian art. Her role as art critic and patron helped launch the careers of artists such as Mario Sironi, Achille Funi, and Carlo Carrà. Her idea of a national art, capable of blending modernity and tradition, remains one of the most important legacies of the Novecento movement.

Margherita Sarfatti remains an ambivalent figure today. On the one hand, she is remembered as a pioneer of Italian art and culture, a woman capable of imposing herself in a world dominated by men. On the other, her closeness to the Fascist regime and her early support for Mussolini cast a shadow over her legacy. Undeniable, however, are the merits that must be credited to Margherita Sarfatti. As soon as she arrived in Milan, together with Anna Kuliscioff, she sought to affirm the role of female intelligence and creativity within the confines of a male, macho, patriarchal world, and Sarfatti herself was not sparing in her criticism of her male colleagues.

What’s more, her contribution was not limited to outlining the poetics of the Novecento group. Meanwhile, Margherita Sarfatti had perfectly sensed the way in which an art system similar to the contemporary one was emerging, made up of gallery owners, artists, journalists and critics sometimes linked together, a system in which she herself was always able to move at ease, writing moreover with a critical style, at once incisive and passionate, capable of grasping emerging trends and placing them in a broader historical and cultural framework.

In addition, Sarfatti was among the first to understand the importance of communication and of what today we would call the... cultural marketing. Indeed, through a network of contacts that ranged from Europe to the United States, she managed to promote Italian art on an international scale, establishing a dialogue with critics, collectors and foreign institutions. His influence (a true “aesthetic colonialism” as scholar Daniela Ferrari has called it) extended far beyond national borders, helping to position Italian art as a major player in the cultural scene of the 20th century.

On the level of art theory, Margherita Sarfatti was a firm believer in an art projected toward the future but in constant dialogue with tradition. While promoting a return to classical values (and yet rejecting a nostalgic classicism), Sarfatti never disavowed the importance of novelty. On the contrary, the twentieth century was characterized by a synthesis between the formal rigor of classicism and the new sensibilities of the twentieth century, to be achieved according to certain fixed points: careful construction, simplicity understood as the renunciation of excesses, decoration and effects, rationality, sobriety.

“For what reason,” wrote Margherita Sarfatti, “does Italian painting, alone among those of the modern age, even in representing men and things of everyday life, give them a halo of immaterial unreality, which transfigures them? I believe I have discovered, after much meditation, the secret. It is that these figures and objects are not employed as definitive material in themselves, chosen and adapted as the raw material of an architectural composition, of which they form a part and of which they provide the limbs. Before being a standing man, a weeping woman, a tree or a fruit jar, these full-bodied images are reasons and motifs of rhythm in space. [...] From the modern goes back to the eternal, and from the random to the final.”

|

| Margherita Sarfatti: who was really the art critic who 'created' the Duce |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.