Florence, scholar confirms Donatello attribution of this crucifix discovered in Legnaia hamlet

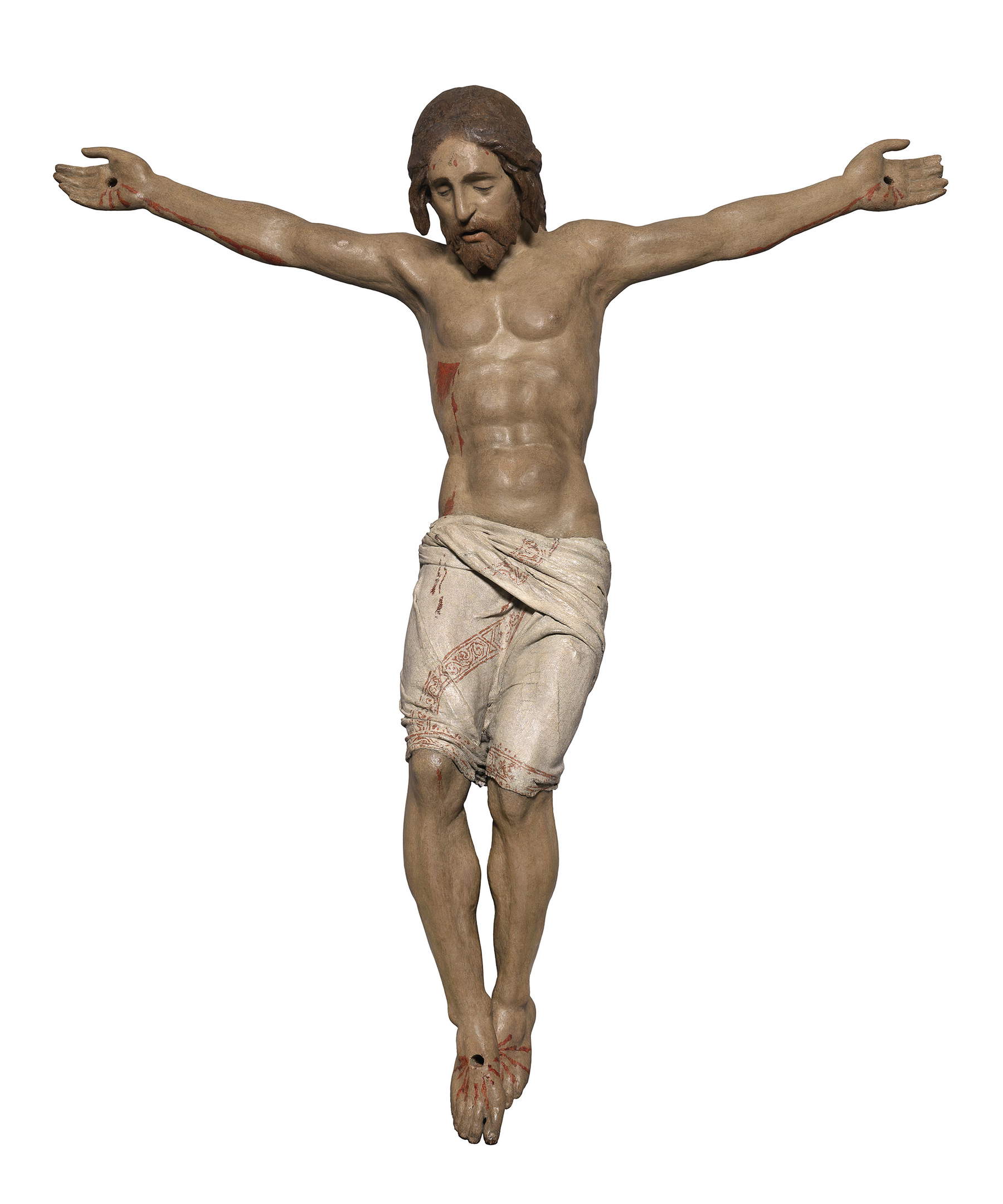

The restoration of the crucifix of the Compagnia di Sant’Agostino in the church of Sant’Angelo a Legnaia (on the outskirts of Florence) has confirmed the attribution of the work to the great Donatello (Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi; Florence, 1386 - 1466), the initiator of the Renaissance in sculpture. It is a work of poplar wood, modest in size (it is 89 centimeters high and 82.5 wide, weighing 3.3 kilograms), hollow inside (in fact, it had to be lightened to enable the members of the confraternity of St. Augustine to carry it easily in procession through the streets of the village of Legnaia), and which has arrived to us in its original wooden structure, substantially well preserved except for the plastic elaboration of the head (formerly completed by a molded plaster covering, unfortunately lost), and the lower ends of the locks of hair.

The work had previously been attributed to Donatello by art historian Gianluca Amato, who dedicated his doctoral thesis (2013) at the University “Federico II” of Naples to wooden crucifixes from Tuscany produced between the late 13th century and the first half of the 16th century: now, the scholar, who made use of the analysis of materials and execution techniques resulting from the restoration work, as well as further comparison of stylistic data, reconstructed the artistic events of the Crucifix and confirmed the assignment to the great 15th-century sculptor. “The authorship of the sculpture,” said Amato, “is based on solid stylistic evidence. On the basis of such evidence the unpublished Crucifix is configured as an emblematic work of Donatello’s late production, datable to the early 1560s. In Legnaia, the artist re-addressed the theme of the Crucifix with a changed attitude compared to his monumental earlier examples, namely the wooden exemplar in Santa Croce in Florence, his early work, and the two witnesses, in wood and bronze, respectively in the church of Santa Maria dei Servi and in the Basilica of St. Anthony in Padua.”

There are several points of contact with other well-known works by Donatello, according to Amato. “Many aspects of the Legnaia carving,” the scholar explains, “offer stringent parallels with the Holofernes in the Medici group of Judith (Florence, Palazzo Vecchio, Sala dei Gigli). Added to this are the similarities between the loincloth, modeled in canvas soaked in glue and plaster, and the intense modulations of the Judith’s copious drapery. The work’s degree of finish seems to have been influenced by the elder sculptor’s personal affairs; from the end of the sixth decade of the fifteenth century Donatello was burdened with numerous commissions that he was not always able to complete. The unpublished Crucifix, therefore, represents a work made by Donatello in the last period of his life. The rediscovered original polychromy, comparable, on a conceptual level, to the drafts of Florentine painters culturally akin to Neri di Bicci, dates back to the final stage of the work.”

The discovery of the Crucifix dates back to January 2012, while the restoration began in late 2014, financed with funds from the Special Superintendence for the Florentine Museum Pole and the City of Florence. Thanks to the joint will of two figures who were very active in Legnaia in those years, parish priest Don Moreno Bucalossi and art historian Anna Bisceglia, an official of the Soprintendenza, the “old” church of Legnaia had seen a series of important restoration works on some of the paintings preserved inside. A few years earlier, the Oratory of Sant’Aurelio, thanks to a benefactor parishioner, had been completely restored (both in its movables and its frescoed surfaces), restoring to this little jewel all its original 18th-century grace.

The restoration of the wooden Crucifix preserved in the anti-cappella of the Oratory thus became the crowning achievement of an important campaign of conservation work at Legnaia. Until then, the Crucifix had not been taken into consideration by studies, and was the object of the exclusive attentions of the parishioners: very dear to the faithful, who guarded it with care, jealously preserved in an environment suitable for spiritual reflection and prayer, but remained in the shadows perhaps because Legniaia is a locality extraneous to the tourist circuits that pass through the Florentine center, and perhaps also because it is little known even among those who, for passion or study, are concerned with historical-artistic heritage. An anonymity that, after all, unites many furnishings of the highest quality still kept in the churches of thehinterland of Florence, located in areas of recent urbanization, certainly peripheral to a “center” such as the Florentine one, yet capable of reserving unexpected and extraordinary surprises.

How relevant was the role played by the Crucifix in the religious life of the community of Legnaia, is evidenced by another aspect that emerged during the restoration: the devotional “excess of zeal” in fact led to the succession in different eras (resumably from the seventeenth century until the second half of the nineteenth century) of as many as five pictorial interventions, both in the body and in the loincloth, and which caused the misrecognition of the real artistic significance of this object and its plastic value, of very high quality.

The restoration of the work, led by Silvia Bensi, was directed by Anna Bisceglia. The work began only after subjecting the work to a campaign of diagnostic investigations designed to identify and analyze the pictorial layers. At a later stage, more detailed data on the conservation of the sculpture and the materials used were collected through a series of scientific, radiographic and photographic documentation analyses. The stratigraphic investigations carried out with a polarizing optical microscope revealed the presence of the five pictorial interventions mentioned above, superimposed, carried out in different periods, and interspersed with at least five films of organic substances. In agreement with the direction of the work, it was decided to remove all the layers of overlapping materials that disfigured the surface of the work, in order to bring out the original carnate, or at any rate the oldest in a chronological sense. The cleaning work was carried out in different stages, layer by layer because various and differentiated were the materials to be removed: starting with oil-binding pigments up to protein-binding pigments. The restoration was accompanied by a digital radiographic survey that provided valuable information about the artifact, such as the excellent preservation of poplar wood, a wood species highlighted by xylological analyses performed by the University of Florence, GESAAF Department, Professor Marco Fioravanti, an important moment of knowledge of the morphological characteristics of the wood.

|

| Florence, scholar confirms Donatello attribution of this crucifix discovered in Legnaia hamlet |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.