by Redazione , published on 19/06/2020

Categories: Art and artists

/ Disclaimer

Bologna is filled with street art works that decline feminism in its various meanings: anti-violence, anti-racism, body and sex positive. It is the project "Struggle is Cool" by the Cheap collective.

Twenty-five street art works meant to represent intersectional, anti-racist, body and sex-positive feminism have invaded the porticos of Via Indipendenza in Bologna: this is The Struggle is FICA, the new public art project of Cheap Festival, an all-female collective founded by six women in the Emilia capital in 2013, and at the same time a public art event held annually in the city.

The works are posters affixed to the columns of the arcades, intended to represent feminist struggles intersecting anti-racism, offer a queer look at gender, and place women’s bodies, trans bodies and eccentric bodies before the public. Twenty-five women artists were called upon to create this work: they are illustrators, graphic designers, performers, cartoonists, and street artists who worked with such a plurality of mediums that they were able to shape a vast sampling of biographies, visions, techniques, ways of thinking about and viewing current events, all united by the perspectives of transfeminism.

The project started significantly after the end of measures to contain the Covid-19 coronavirus infection: during the weeks of the so-called lockdown, so many women who were unsafe in their homes because they lived with violent men were forced to remain segregated in their homes, and the issue of gender-based violence was ignored within institutional public discourse. And again, schools were closed and never reopened, setting up another problem related to gender roles, namely the division of labor, which for women typically entails greater responsibility for domestic care. The closure of schools has thus increased this demand, likely causing many women to abandon paid work especially where remote work ( smart working) could not be implemented. And again, the health emergency has also affected the displacement of economic resources away from sexual, reproductive, and maternal health services: in a country where counseling centers were insufficient before the virus arrived, it is legitimate to fear that many women will not be guaranteed the right to access basic health services.

“This pandemic,” declares the Cheap collective, "has worked in various areas as an accelerator that has imposed a terrible reality check on us: within this crisis, pre-existing gender gaps have widened. In such a scenario restarting from feminism cis only seems like an act of common sense. The project had been in the works since January, but there is no coincidence: we are finally witnessing a paradigm shift. In Bristol, the statue of slaver Edward Colston was removed and thrown into the river; in the United States several statues of Christopher Columbus have been removed. In Milan, something has been asserted that we find disconcertingly trivial, namely, that a rapist does not deserve a statue and through it a public celebration: yet we have witnessed a chilling rising of shields in defense of a white supremacist who spoke of his child slave as a ’docile pet.’ We are not sure that the defense of white male and colonial privilege will stop with the array of Montanelli’s toddlers who are tearing their hair out, arguing that ’rape must be contextualized.’ Instead, we fear that not only will we witness such unworthy scenes whenever a symbol of oppression is challenged, but that the same situation will be repeated when we try to produce critical imagery in opposition to the above."

It is, the collective concludes, a “public art intervention that speaks of feminism, of the connection of systemic power in functionally generating sexism and racism, of the need to elaborate tools of decolonization, to represent bodies that proudly eschew whiteness or heteronormativity or the binary view of gender: just as we know that you are not ready to eliminate symbols of privilege, we think it is time that you come to terms with those of our liberation as well. Exactly as it is happening in the rest in the world: the real debate in contemporary art today is around decolonization as an artistic practice and concerns all the figures involved (women artists, curators, museums, collectors, ADs, critics, writers). Decolonization is THE issue. For us it connects intersectionally to other major issues of feminism addressed in the art practice of women whose work is a reference for us: the Guerrilla Girls, with whom we collaborated in 2017, have for years focused on the question of the gender gap within the art system; Tania Bruguera was a guest artist in Bologna at the biennial Atlas of Transitions, where she made an intervention between public art and participatory art that dissected the themes of migration and borders, a colonial legacy; Kara Walker today pursues an extraordinary path on blackness, a path that works on other very heavy colonial legacies and the remnants of white supremacism.”

Several themes are addressed in the twenty-five posters. For example, the theme of nudity recurs, and the thought that nudity might be a problem is greeted by Cheap with a certain resignation (“the problem,” they say, “is not nudity, although surely someone will give signs of decompensation in front of deicapezzoli and use the thing instrumentally: in Italy the problem is free women who self-determine. For too long women have been represented by the male gaze: in this, too, there is a paradigm shift taking place in front of which there is the usual resistance that leads to problematizing women who represent themselves in a nude that is not heroic but expresses power, to shouting at the scandal of women who go from being objects to subjects of desire.”)

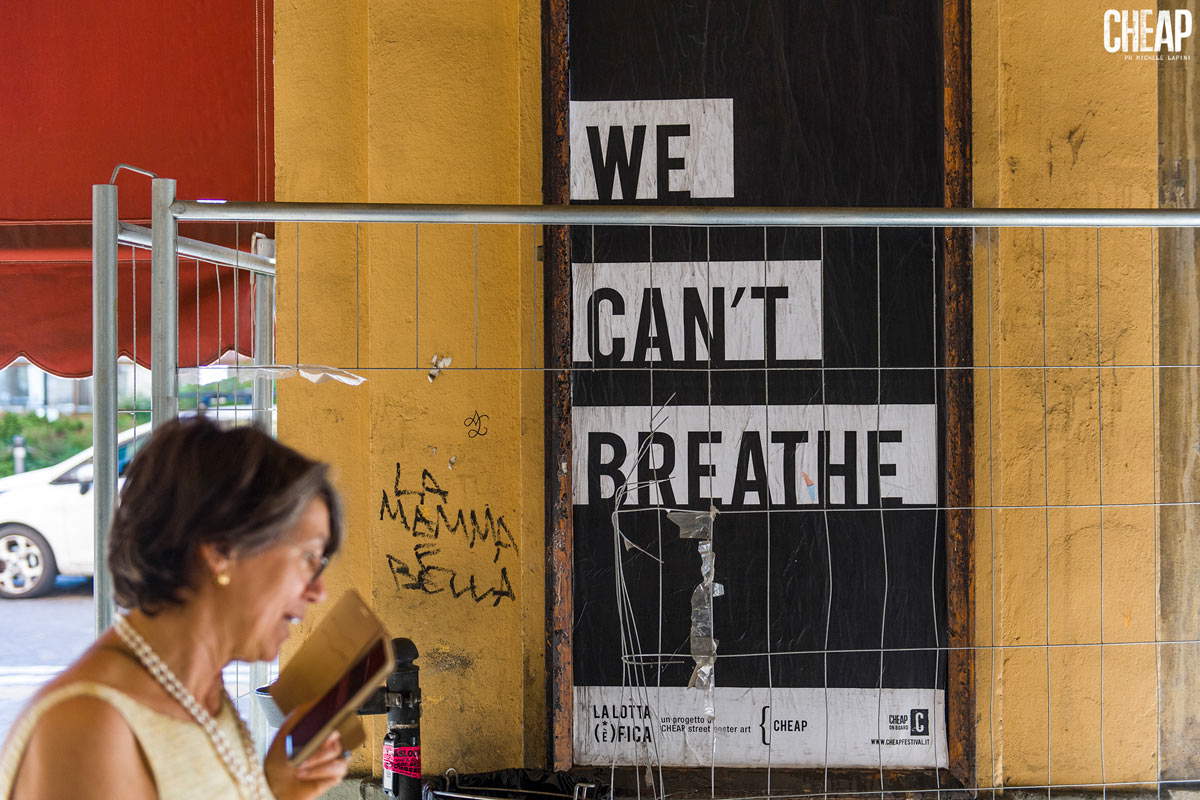

Then there is the feminist narrative, there are trans bodies made by trans people, such as the lposters of the illustrator and cartoonist Josephine Yole Signorelli (also known by the pseudonym “Fumettibrutti”), a publishing case with P. my trans adolescence released by Feltrinelli Comics: her manifesto addresses the fetishization to which trans bodies are subjected. Again, there are the themes of anti-racism and anti-colonial perspective, present in the posters by illustrator Rita Petruccioli, Argentinian artist Mariana Chiesa, visual designer Ilaria Grimaldi and American street artist The Unapologetically Brown Series, the latter at her first try in Italy. There is also a poster created by the Cheap team, with the typographic inscription WE can’t breathe, a reference and expression of closeness to the struggles of Black Lives Matter after the murder of George Floyd, but also a way to emphasize a local problem, namely the fact that, according to Cheap, Italy is a racist country without knowing it is racist, as well as a country with a colonial history and with a still in some ways colonial look, nevertheless not perceived.

Two posters by two international artists are dedicated to gender-based violence: Bastardilla, a Colombian street artist who evokes data on the incidence of violence within the walls of the home; MissMe, an artist based in Canada who was previously a guest of Cheap in Bologna, who instead claims anger as a tool of struggle. Finally, mention is made of Joanna Gniady ’s manifesto on feminist struggles in Poland, Ivana Spinelli ’s contribution from Gimbutas’ suggestions and infected by Haraway’s lesson, Cristina Portolano ’s sex positive posters and Chiaraliki’s art, the claims of fat queer activism in Chiara Meloni’s images, Giorgia Lancellotti’s pop intersectionality, Maddalena Fragnito ’s questioning of what is essential in a sharp critique of capitalism, perfomer Silvia Calderoni ’s body positive posters and the one signed by Claudia Pajewski & Camilla Carè, the trans mermaids of Nicoz Balboa, the binomial “amor y lucha” that runs like a fuchsia thread through the posters of Athena, Luchadora, Ritardo and Jul’Maroh, the sisterhood illustrated by Flavia Biondi, the visual divertissement of Redville that plays with the title of the project, the hermaphrodite snails released by the queer body designed by To / LeT.

Below is a selection of works from the project The Struggle is FICA. All images are by photographer Michele Lapini.

|

| Rita Petruccioli |

|

| Luchadora |

|

| Claudia Pajewski and Camilla Caré |

|

| Nicoz Balboa |

|

| Silvia Calderoni |

|

| Bastardilla + Church |

|

| Athena |

|

| Giorgia Lancellotti |

|

| MissMe |

|

| Joanna Gniady |

|

| Fumettibrutti |

|

| Cristina Portolano |

|

| Ilaria Grimaldi |

|

| Cheap |

|

| Chiara La Scura |

|

| The Unapologetically Brown Series |

|

| Bologna, Via Indipendenza invaded by feminist, anti-racist, queer street art: the struggle is cool. Photos |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.