An end and not a means. The 100 years of the Ravenna Mosaic School.

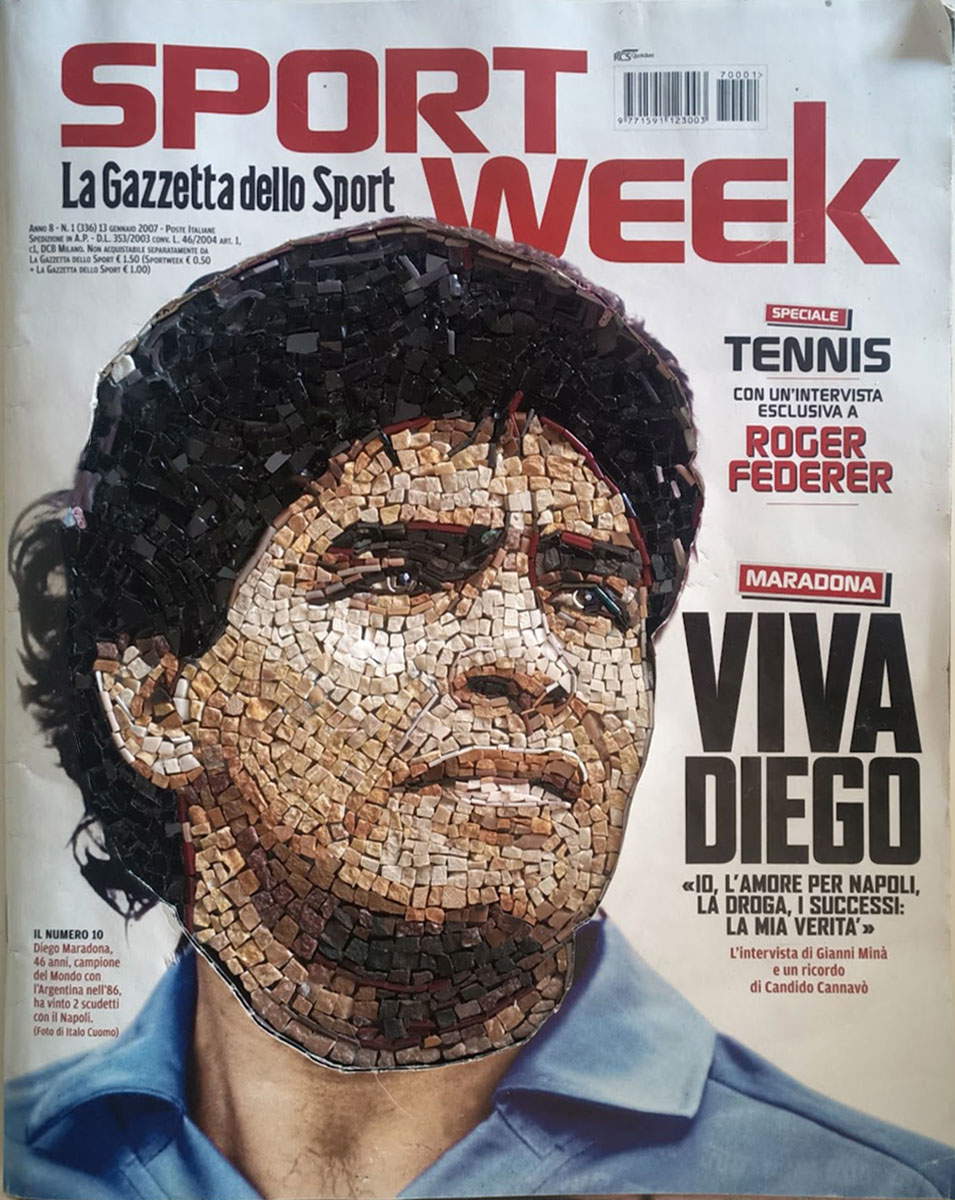

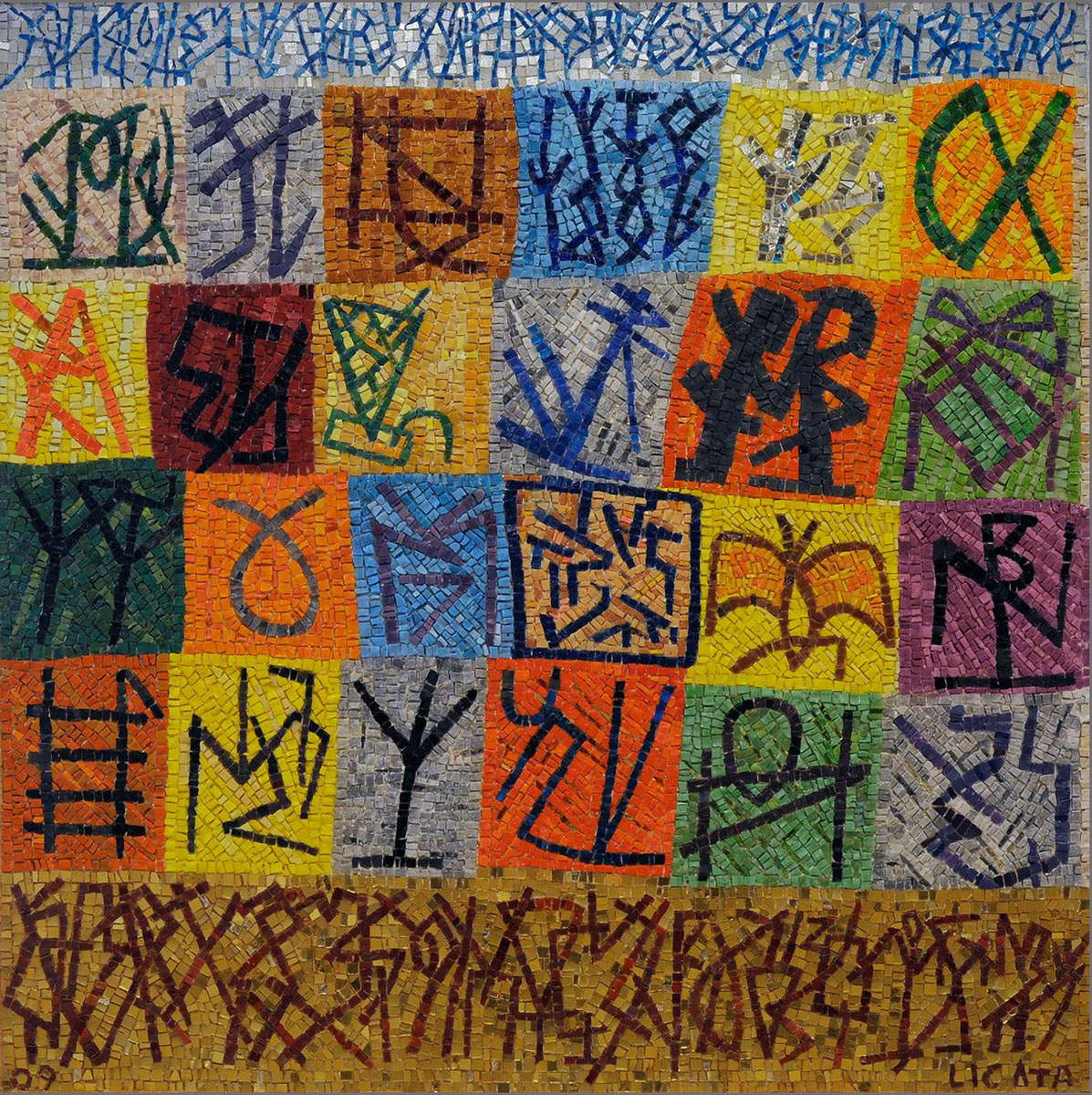

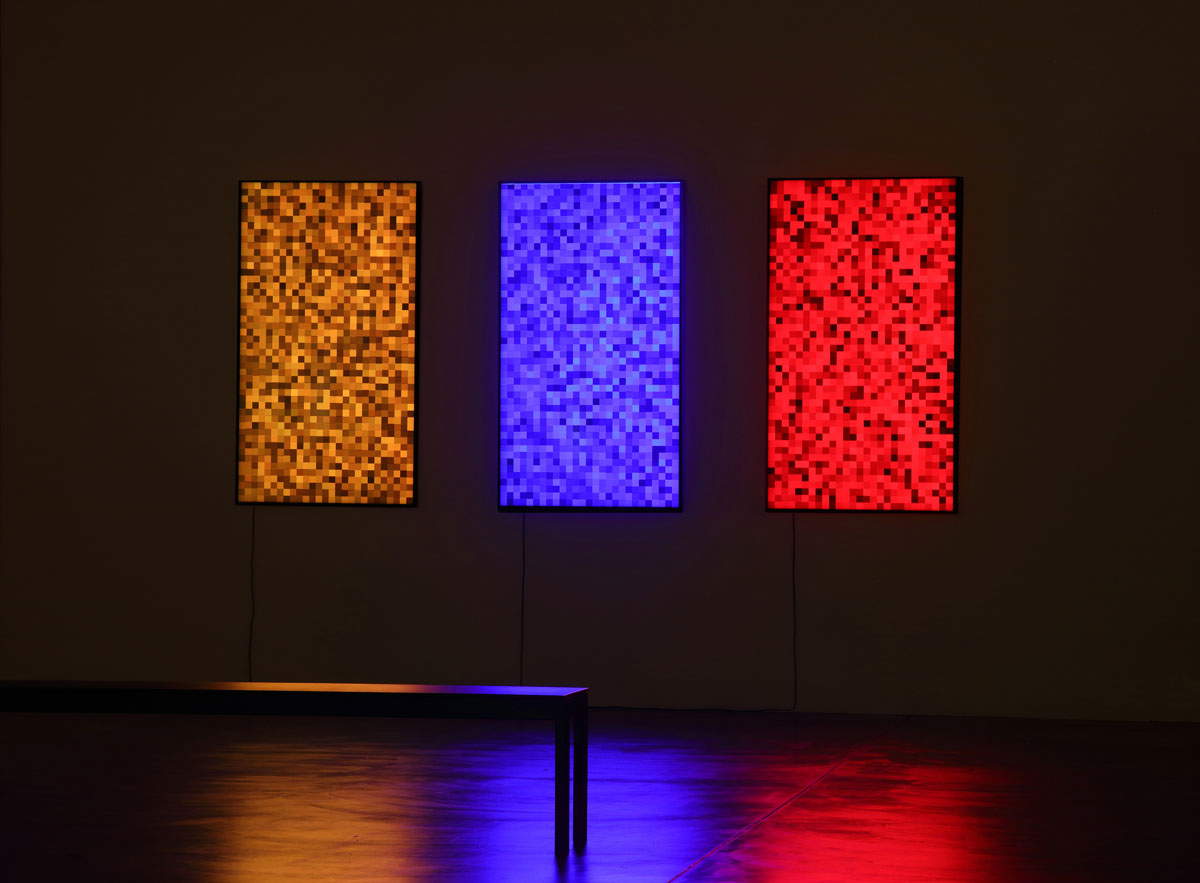

Exactly 100 years ago, in 1924, the Mosaic School of theRavenna Academy of Fine Arts was born. To commemorate the centennial (1924-2024), the Academy has initiated a program of initiatives that include reviews, conferences and publications designed to engage the city of mosaics and its inhabitants. From Oct. 12 to Jan. 12, 2025, the MAR - Museum of Art of the City of Ravenna, which houses a vast collection of contemporary mosaics, presents the exhibition I’m a Mosaic! From Severini, Sironi, Fontana to Paladino, Plessi and Samorì. The exhibition, under the curatorship of Paola Babini, Giovanna Cassese, Emanuela Fiori and Giovanni Gardini, traces a century of history from the time of the school’s founding and sheds light on theevolution of mosaic.

We know: Ravenna has always been known as the city of mosaics, but why did she in particular become so closely associated with this art form? The answer goes back to a crucial moment in history, around 402 AD, when the capital of theWestern Roman Empire was moved from Milan to Ravenna. The choice was dictated by several strategic reasons. First, Ravenna’s location on the Adriatic Sea facilitated connections with Constantinople, the capital of theEastern Roman Empire. In addition, the city was easily defensible against barbarian attacks due to its location protected to the east by the sea and to the west by marshes. Throughout the fifth and sixth centuries, Ravenna was enriched with buildings that were meant to reflect its new political and cultural centrality. The capital’s buildings, initially expressions of the late Roman empire, with works by artists who still followed the narrative canons of classical art, increasingly developed toward a Christian aesthetic, focusing on the essential. The transformation resulted in the influence suffered from the proximity to theByzantine Empire. For this reason, the interiors of churches, instead of being decorated with frescoes, were covered with mosaics made of small cubes of stone or glass capable of reflecting warm light and bright colors. All this gave the buildings an aura of sacredness and power.

Today, Ravenna’s mosaic tradition continues to attract millions of visitors fascinated by masterpieces such as the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, which preserves inside its mosaic decorations emphasized by the golden light coming in through the windows, or the Basilica of San Vitale, included in 1996 in the UNESCO World Heritage List, among the most significant monuments of early Christian art, or again Sant’Apollinare in Classe, also one of the UNESCO monuments. Although the legacy of Byzantine art continues to be the centerpiece of the city, few know that Ravenna holds an equally precious wealth descended from that same tradition: modern and contemporary mosaics. But to whom do we owe the rediscovery and continuity of this ancient technique in modern Ravenna? And what role has the Academy of Fine Arts played in preserving and innovating its historical and artistic heritage?

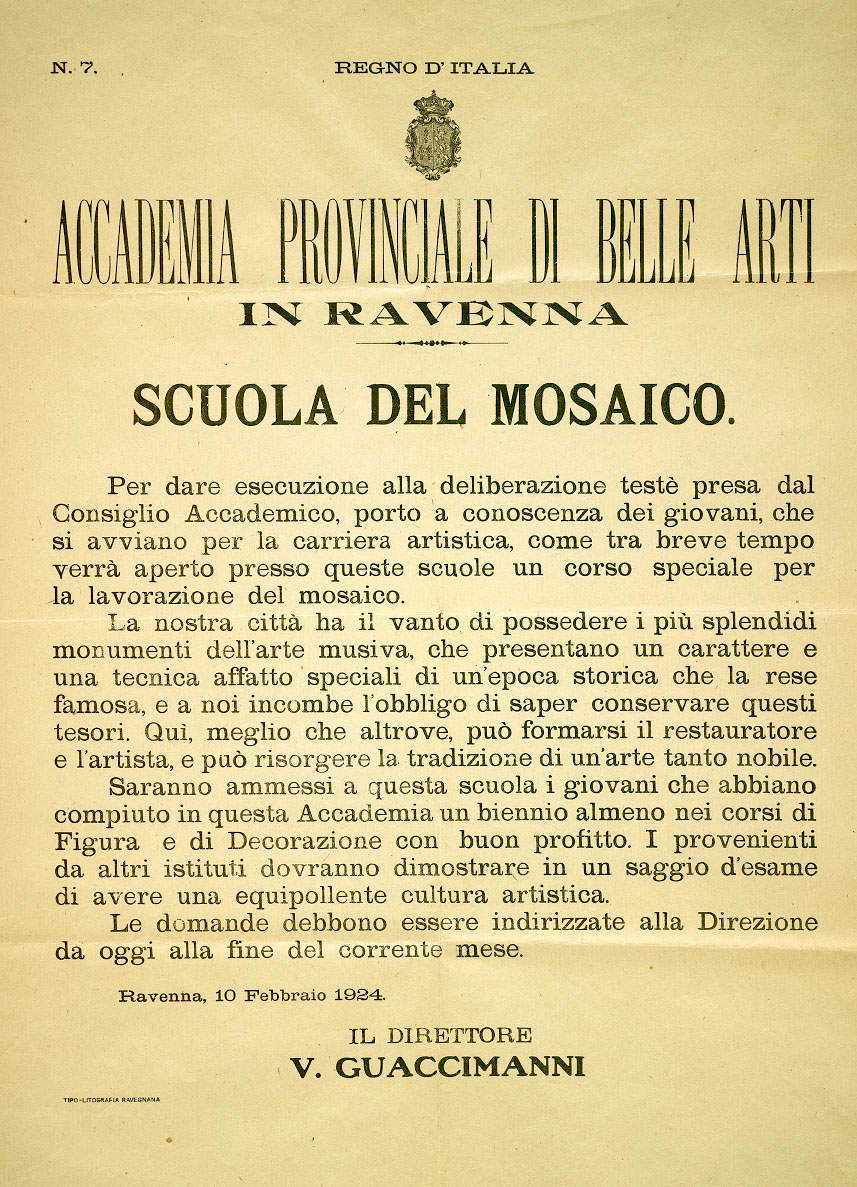

One of the great protagonists of the renewal of the Academy was the architect and painter Giovanni Guerrini (Imola, 1887 - Rome, 1972). Guerrini embodied an innovative mentality that led him to rediscover the city’s mosaic vocation, promoting in 1924 the founding of the Novecento Mosaic School within the Academy itself. The artist Vittorio Guaccimanni (Ravenna, 1859-1938), linked to the Macchiaiolo movement, was called to preside over the school. The proclamation, issued on February 10, 1924, for the opening of the Mosaic School was addressed to “young people, who are setting out for an artistic career,” emphasizing the importance of Ravenna, a city that “has the pride of possessing the most splendid monuments of mosaic art, which present a character and technique quite special to a historical era that made it famous.” The goal of the call was thus quite clear: to train restorers and artists capable of preserving and renewing those treasures, so that that “so noble” tradition could live on. Enrico Galassi (Ravenna, 1907 - Pisa, 1980), who studied at the same School of Mosaic had understood since the late 1920s the need to overcome the Byzantine tradition of mosaic, conceiving it as “an art for its own sake and no longer a mere means.” His vision was expressed in four articles published in Corriere Padano between 1927 and 1930 and later confirmed in a letter sent to journalist and art critic Pietro Maria Bardi in the 1940s. To that point, under the direction of painter Giuseppe Zampiga (Ravenna, 1860-1934), the School adopted a conservative approach, later modernized by his pupil Renato Signorini, who took the reins until 1976. Zampiga, a restorer of Ravenna’s Byzantine mosaics, had deep ties to the city’s mosaic tradition, as evidenced by his contribution in producing the plates for Monumenti edition . Historical Tables of the Mosaics of Ravenna, produced together with Alessandro Azzaroni in 1930. The work, sponsored by the Royal Institute of Archaeology and Art History in Rome, includes representations of Ravenna’s mosaics through 133 monochrome and polychrome plates such as those of San Vitale, Sant’Apollinare Nuovo and the Baptistery of the Arians.

Some of Ravenna’s most important artists and restorers were trained at the Mosaic School, such as Romolo Papa, Renato Signorini, Ines Morigi Berti, Isler Medici, Antonio Rocchi, Eda Pratella, Sergio Cicognani and Libera Musiani, who, as a result of the growing need to preserve the city’s vast mosaic heritage, founded the Mosaicists Group of the Ravenna Academy of Fine Arts in 1948. The artists thus began to dedicate themselves with constant commitment to the restoration of mosaics under the guidance of the Superintendency of Fine Arts established in 1897. The Group, which boasted the title Accademia delle Belle Arti (Academy of Fine Arts) in its name, had close ties to the institution: in fact, it undertook to hire and employ exclusively students from the Ravenna Academy within its workshop. In the early years, its main activity was restoration, made urgent by the damage caused by the bombing and destruction of the war that had severely compromised Ravenna’s mosaic heritage. Among the numerous restorations and detachments of works of art by the Mosaicists Group of the Academy were those in the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare in Classe that took place between 1948 and 1949, the detachment of the mosaics of the triumphal arch dating from the 6th to 9th centuries; the detachment of the mosaics of the 6th-century presbytery vault in the Basilica of San Vitale between 1962 and 1964; and the detachment of the mosaics of the lunette, barrel vault, dome, and sub-arch dating from the 5th-6th centuries in the Archbishop’s Chapel between 1965 and 1966. In fact, the restoration and conservation work lasted until 2021 with the installation of 96 mosaics within the Tornareccio municipality for the contemporary art exhibition A Mosaic for Tornareccio.

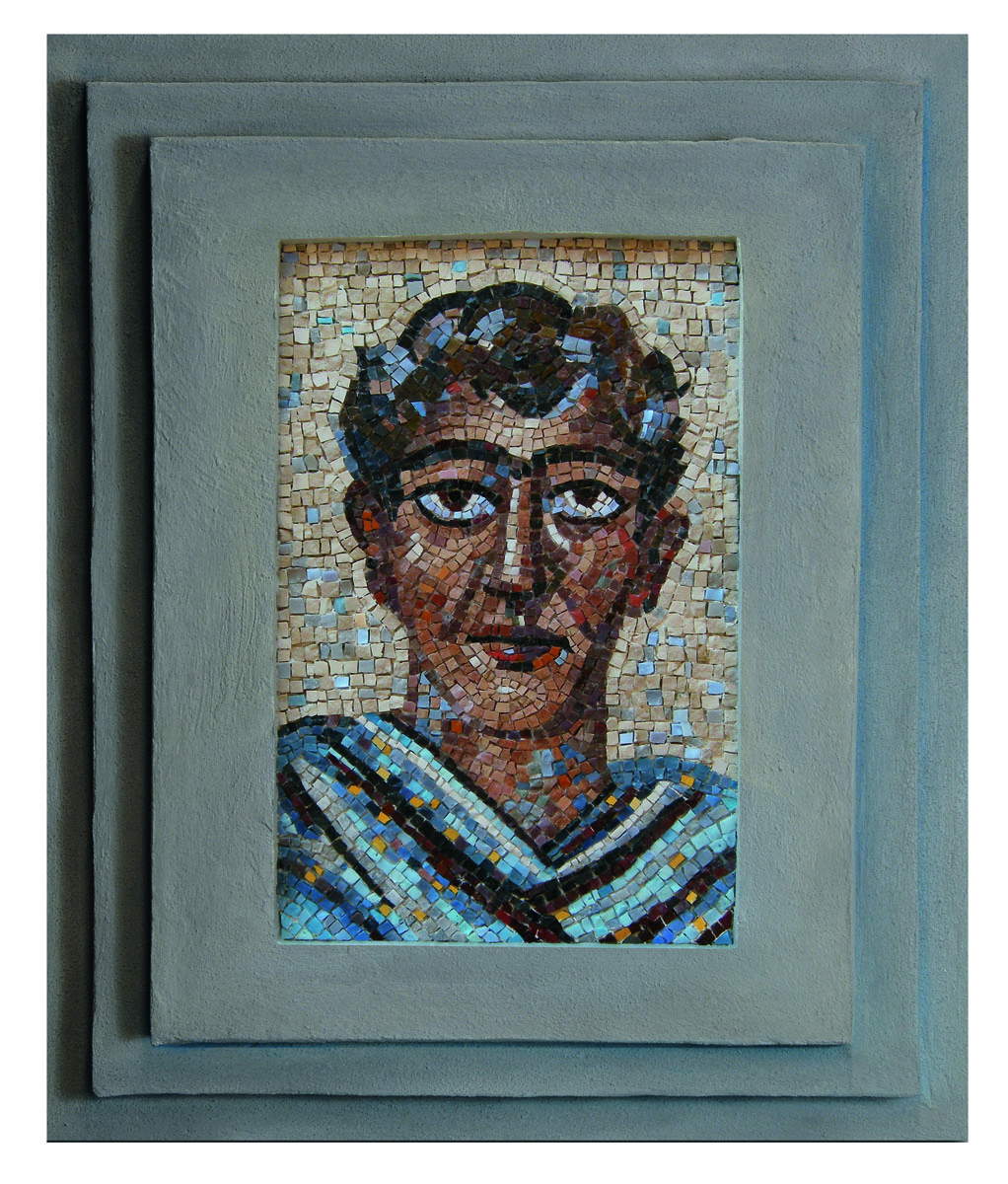

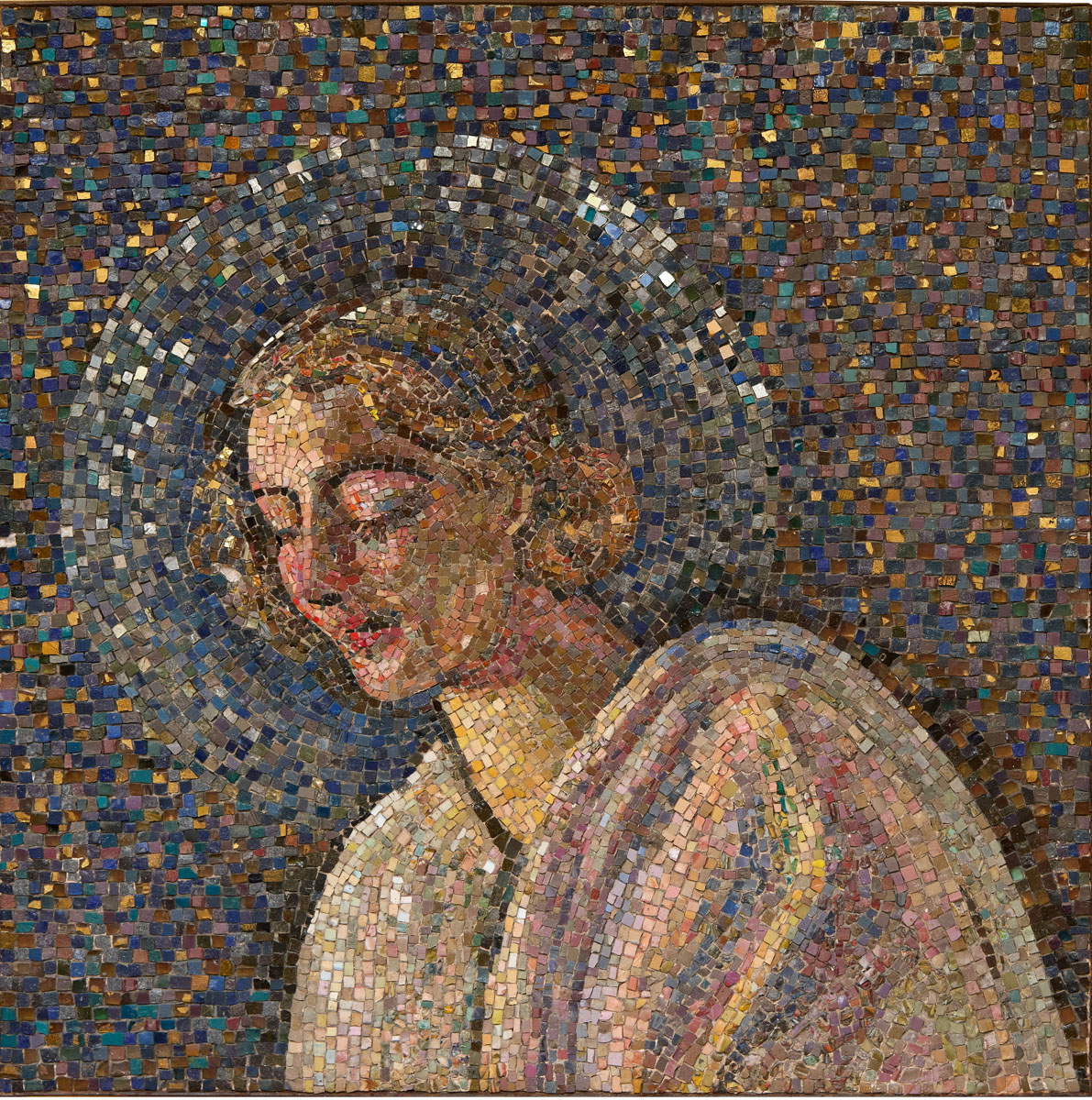

The constant relationship with the past therefore gave the Group’s members the opportunity to study mosaics in depth by analyzing their different values: from chromatic ones to material characteristics, the cut and laying of the tesserae. The restorers, whose company at that time consisted of Alessandro Azzaroni, Giuseppe Zampiga, Libera Musiani, Sergio Cicognani and Ines Morigi Berti, traced the cartoons with tracing paper and carefully surveyed the shape of each tessera, reproducing the hue of the enamels and marbles in great detail, using watercolor techniques. The main objective of the project was conservation in nature, and the traced cartoons were not only tools for protection; they were also used within the Academy to train young mosaicists. Giuseppe Bovini, inspector at the Soprintendenza ai Monumenti della Romagna since 1950 and director of the National Museum, together with Professor Teodoro Orselli, then director of the Academy of Fine Arts, conceived the idea of freeing the Ravenna mosaics from the constraints of the walls on which they were originally applied. The faithfully reproduced copies on a 1:1 scale became accessible to an international audience, and from 1951 they were featured in a traveling exhibition entitled Exhibition of Copies of Ancient Mosaics, which opened in Paris and was subsequently hosted in numerous cities around the world. After the success of the 1951 exhibition, Giuseppe Bovini and Giuseppe Salietti, the first president of the Mosaicists Group of the Academy of Fine Arts, wished to highlight the contemporary nature of mosaic art. With the help of figures such as art critics Giulio Carlo Argan and Palma Bucarelli, they invited a group of contemporary painters, including Afro, Birolli, Cagli, Campigli, Capogrossi, Cassinari, Chagall, Corpora, Deluigi, Gentilini, Guttuso, Mathieu, Mirko, Moreni, Paulucci, Reggiani, Saetti, Sandqvist, Santomaso and Vedova, to create a pictorial work that would later be transformed into mosaic. The master mosaicists (all members of the Academy’s Gruppo Mosaicisti) involved in the realization were several. They include Antonio Rocchi, Ines Morigi Berti, Renato Signorini, Libera Musiani, Isler Medici, Romolo Papa, Sergio Cicognani and Zelo Molducci. The Exhibition of Modern Mosaics was thus inaugurated on June 7, 1959 in the refectory of the San Vitale Monastery in Ravenna. The two exhibitions, together with the Exhibition of Mosaics with Dantesque Subjects held in 1965 on the occasion of the 7th centenary of Dante Alighieri’s birth, marked at this point the reconfirmation of Ravenna as the “City of Mosaics.”

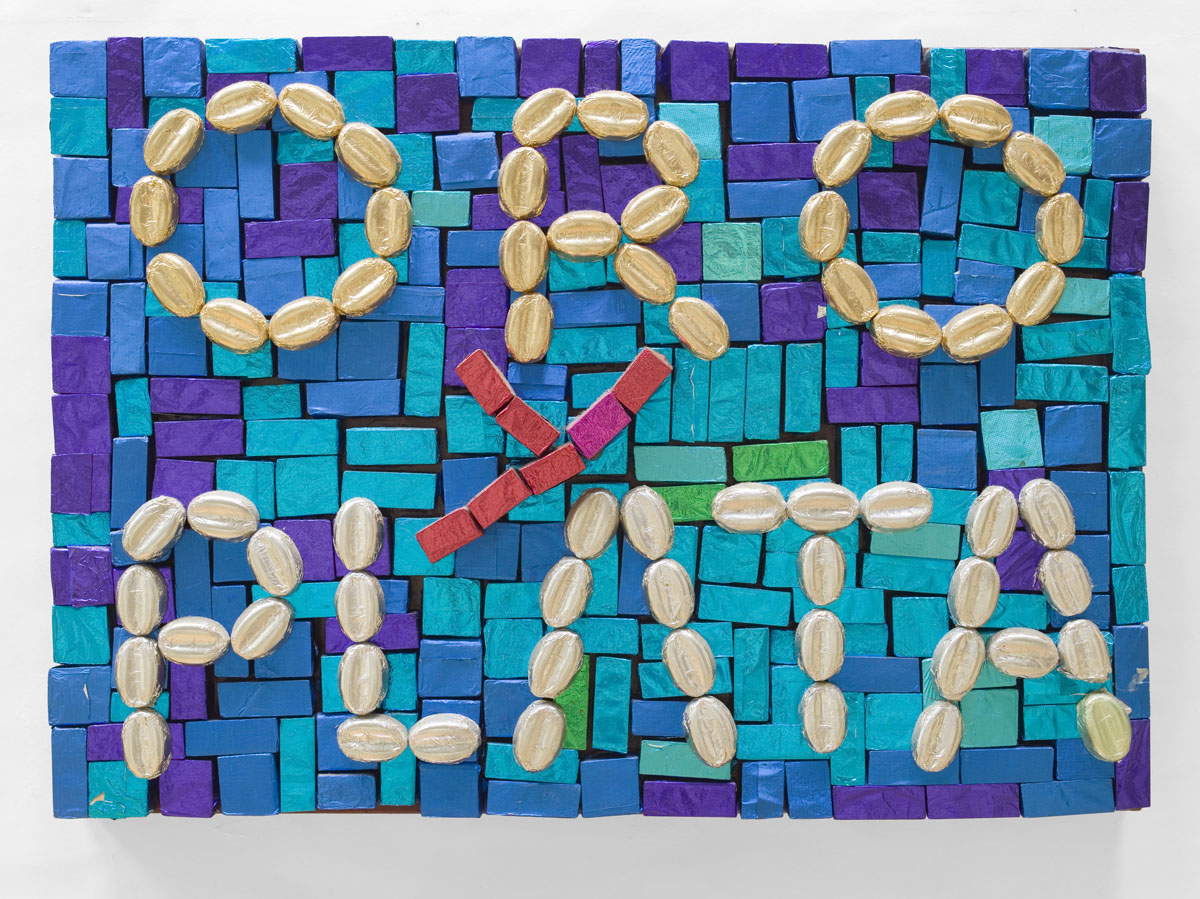

To this day, under the leadership of restorer and artist Marco Santi, the Gruppo Mosaicisti, which became an independent company in 2008, continues to create and restore works of art. In this year the Ravenna Academy of Fine Arts, which in 2023 assumed the status of a state institution under the leadership of Professor Paola Babini, pays tribute to the history that has distinguished Ravenna for millennia and continues to shape young artists and mosaicists. Inspired by the Byzantine tradition and the legacy left by the Academy’s Mosaicists Group, young people reinvent the language of mosaic and explore new forms of contemporary expression.

|

| An end and not a means. The 100 years of the Ravenna Mosaic School. |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.